A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Accent

ACCENT. As in spoken language certain words and syllables receive more emphasis than others, so in music there are always some notes which are to be rendered comparatively prominent; and this prominence is termed ‘accent.’ In order that music may produce a satisfactory effect upon the mind, it is necessary that this accent (as in poetry) should for the most part recur at regular intervals. Again, as in poetry we find different varieties of metre, so in music we meet with various kinds of time; i.e. the accent may occur either on every second beat, or isochronous period, or on every third beat. The former is called common time, and corresponds to the iambic or trochaic metres; e.g.

‘Away! nor let me loiter in my song,’

or

‘Fare thee well! and if for ever.’

When the accent recurs on every third beat, the time is called triple, and is analogous to the anapaestic metre; e.g.

‘The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold.’

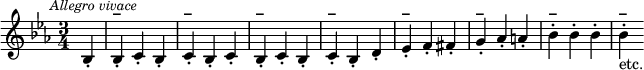

As a general rule the position of the accent is indicated by bars drawn across the stave. Since the accents recur at regular intervals it follows of course that each bar contains either the same number of notes or the same total value, and occupies exactly the same time in performance, unless some express direction is given to the contrary. In every bar the first note is that on which (unless otherwise indicated) the strongest accent is to be placed. By the older theorists the accented part of the bar was called by the Greek word thesis, i.e. the putting down, or ‘down beat,’ and the unaccented part was similarly named arsis, i.e. the lifting, or ‘up beat.’ In quick common and triple time there is but one accent in a bar; but in slower time, whether common or triple, there are two—a stronger accent on the first beat of the bar, and a weaker one on the third. This will be seen from the following examples, in which the strong accents are marked by a thick stroke (─) over the notes, and the weak ones by a thinner (―).

1. 100th Psalm.

2. Beethoven, Eroica Symphony (Scherzo).

3. Beethoven, Symphony in C minor (Finale).

4. Haydn, Quartett, Op. 76, No. 1 (1st movement).

5. Mozart, Symphony in E flat.

![\relative c' {\clef treble

\key aes \major

\time 2/4

\override Score.RehearsalMark #'break-align-symbol = #'time-signature

\mark \markup { \small \italic "Andante" }

ees4^\markup{\bold –} f16.^\markup{–}([ g32 aes16. f32)] |

ees8^\markup{\bold –} r8 aes16.^\markup{–}[ g32 bes16. aes32] |

c16.^\markup{\bold –}[ bes32 d16. c32] ees8^\markup{–} ees |

ees4(^\markup{\bold –} ees,8)^\markup{–} r8 |

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/d/ednvrjyyp5dp0a6nsyq5ilkq8jj6tac/ednvrjyy.png)

6. Beethoven, Trio, Op. 70, No. 2 (3rd movement).

7. Mendelssohn, 'Pagenlied.'

The above seven examples show the position of the accents in the varieties of time most commonly in use. The first, having only two notes in each bar, can contain but one accent. In the second and third the time is too rapid to allow of the subsidiary accent; but in the remaining four both strong and weak accents will be plainly distinguishable when the music is performed.

It will be observed that in all these examples the strong accent is on the first note of the bar. It has been already said that this is its regular position; still it is by no means invariable. Just as in poetry the accent is sometimes thrown backward or forward a syllable, as for instance in the line

- ‘Stop! for thy tread is on an Empire's dust,’

where the first syllable instead of the second receives the accent, so in music, though with much more frequency, we find the accent transferred from the first to some other beat in the bar. Whenever this is done it is always clearly indicated. This may be done in various ways. Sometimes two notes are united by a slur, showing that the former of the two bears the accent, in addition to which a sf is not infrequently added; e.g.

8. Haydn, Quartett, Op. 54, No. 2 (1st movement).

9. Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 27, No. 1 (Finale).

![{ \time 2/4 \key c \minor \partial 8 { \set doubleSlurs = ##t <e' bes>8([\sf | <f' a>)] <e'' bes'>([\p <f'' a'>)] <e' bes>([^\sf | <f' a>)] <bes'' e''>([\p <a'' f''>)] <e' bes>([^\sf | <f' a>)] <e'' bes'>([\sf <f'' a'>)] <e''' bes''>([\sf | <f''' a''>)] <e'' bes'>([\sf <f'' a'>)] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/r/er2d03s26zbzgb6db2olpylramh36lj/er2d03s2.png)

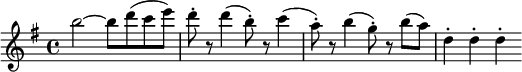

In the former of these examples the phrasing marked for the second and third bars shows that the accent in these is to fall on the second and fourth crotchets instead of on the first and third. In Ex. 9 the alteration is even more strongly marked by the sf on what would naturally be the unaccented quavers. Another very frequent method of changing the position of the accent is by means of Syncopation. This was a favourite device with Beethoven, and has since been adopted with success by Schumann, and other modern composers. The two following examples from Beethoven will illustrate this:

10. Symphony in B♭ (1st movement).

11. Sonata, Op. 28 (1st movement).

In the following example,

12. Schumann, Phantasiestücke, Op. 12, No. 4.

will be noticed not merely a reversal of the accent, as in the extracts from Beethoven previously given, but also in the last three bars an effect requiring further explanation. This is the displacing of the accents in such a way as to convey to the mind an impression of an alteration of the time. In the above passage the last three bars sound as if they were written in 2-4 instead of in 3-4 time. This effect, frequently used in modern music, is nevertheless at least as old as the time of Handel. A remarkable example of it is to be found in the second movement of his Chandos anthem ‘Let God arise.’

As instances of this device in the works of later composers may be quoted the following:

14. Beethoven, Eroica Symphony (1st movement).

15. Weber, Sonata in C (Menuetto).

In both these passages the accent occurring on every second instead of on every third beat, produces in the mind the full effect of common time. It is in quick movements that this modification of the accent is most often found; that it may nevertheless be very effectively employed in slower music will be seen from the following example, from the Andante of Mozart's ‘Jupiter’ Symphony, in which, to save space, only the upper part and the bass are given. It will be noticed that the extract also illustrates the syncopation above referred to.

![{ \time 3/4 << { \key f \major \relative c''' { \mark \markup \small "16." c8\fp[ ~ c16 g8( ees c16)] c'8\fp[ ~ c16( aes] ~ | aes[ f8 c16)] c'8\fp[ ~ c16 g8( e c16)] | c'8\fp[ ~ c16 aes8( f c16)] ees'8\fp[ ~ ees16( c)] | } }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key f \major \relative c, { ees8^\fp[ ees' ees ees] f,^\fp[ f'] | f[ f] g,^\fp[ g' g g] | aes,^\fp[ aes' aes aes] a,[^\fp a']^\markup { \null \raise #3 \smaller { etc. } } } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/6/k6xhmcy9l2uoaw39r7m76iso7ph7e7s/k6xhmcy9.png)

A nearly analogous effect the displacing of the accents of 6-8 time to make it sound like a bar of 3-4 time is also sometimes to be met with ; e. g. in the Andante of Mozart's Symphony in G minor—

![{ \time 6/8 \key c \minor \mark \markup \small "17." \relative c' { \grace { d16\f[ bes'] } bes'4 bes, bes8 bes ~ | bes a32([ c)] r16 bes32( d) r16 c32( ees) r16 r8 r | } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/f/8ffsumctnmru0dv28v1crvs6724mf8t/8ffsumct.png)

The reverse process—making a passage in common time sound as if it were in triple—is much less frequently employed. An example which is too long for quotation may be seen in the first movement of Clementi's Sonata in C, op. 36, No. 3. Beethoven also does the same thing in the first movement of his symphony in B flat.

Though no marks of phrasing are given here, as in some of the examples previously quoted, it is obvious from the form of the passage, which consists of a sequence of phrases of three minims each, that the feeling of triple time is conveyed to the hearer. In this contradiction of the natural accent lies the main charm of the passage.

In the well-known passage in the scherzo of the 'Eroica' symphony, where the unison for the strings appears first in triple time

and immediately afterwards in common time

there is not exactly (as might be imagined at first sight) a change of accent; because the bars are of the same length in both quotations, and each contain but one accent, which in the first extract comes on the second instead of the first beat. The difference between the two passages, apart from the sf in the first, consists in the fact that in the former each accent is divided into three and in the latter into two parts. The change is not in the frequency with which the accents recur, but in the subdivision of the bar.

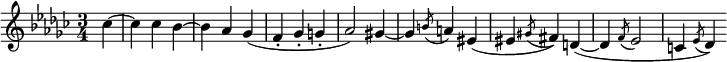

Another displacement of accent is sometimes found in modern compositions, bearing some resemblance to those already noticed. It consists in so arranging the accents in triple time as to make two bars sound like one bar of double the length; e.g. two bars of 3-8 like one of 3-4, or two of 3-4 like one of 3-2. Here again the credit of the first invention is due to Handel, as will be seen from the following extract from his opera of 'Rodrigo.'

![{ \time 3/8 \mark \markup \small "21." \relative c'' { \autoBeamOff r8 e g | e4 d8 ~ | d c d | g,([ c16 b] c8) | r d e | f4 e8 ~ | e d c | d16([ c b c d8)] | }

\addlyrics { Si che lie -- ta go -- de -- ro, e la pa -- ce __ tro -- ve -- ro __ } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/c/ic002eutcsmnl21vw51b9cyr3k5e6tv/ic002eut.png)

When forty years later Handel used this theme for his duet in 'Susanna,' 'To my chaste Susanna's praise,' he altered the notation and wrote the movement in 3-4 time.

Of the modern employment of this artifice the following examples will suffice:

22. Schumann, P.F. Concerto (Finale).

23. Brahms, 'Schicksalslied.'

At first sight the second of these examples seems very like the extract from Handel's 'Let God arise.' The resemblance however is merely external, as Brahms's passage is constructed on a sequence of three notes, giving the effect of 3-2 time, while Handel's produces the feeling of common time.

It will be seen from the above extracts what almost boundless resources are placed at the disposal of the composer by this power of varying the position of the accent. It would be easy to quote at least twice as many passages illustrating this point; but it must suffice to have given a few representative extracts showing some of the effects most commonly employed. Before leaving this part of the subject a few examples should be given of what may be termed the curiosities of accent. These consist chiefly of unusual alternations of triple and common-time accents. In all probability this peculiar alternation was first used by Handel in the following passage from his opera of 'Agrippina.'

![{ \time 3/8 { \key g \major \relative g' { \mark \markup \small "24." \autoBeamOff g8 b16([ a g8)] | g b16([ a g8)] | \time 2/4 e'4 d | \time 3/8 c b8 | a c16([ b a g)] | a4. } }

\addlyrics { Bel pia ce -- re e go -- de -- re fi -- "do a" -- mor! } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/6/l6z0sa47qljwv5tzekvuy7kgrwk7x3m/l6z0sa47.png)

In the continuation of the song, of which the opening bars are given here, the alternations of common and triple time become more frequent. In the rare cases in which bars of 3-4 and 2-4 time alternate, they are sometimes written in 5-4 time, the accent coming on the first and fourth beats. An example of this time is found in the third act of Wagner's 'Tristan und Isolde,' in which the composer has marked the secondary accent by a dotted bar.

A similar example, developed at greater length, may be seen in the tenor air in the second act of Boieldieu's 'La Dame Blanche.'

One of the most interesting experiments in mixed accents that has yet been tried is to be found in Liszt's oratorio 'Christus.' In the pastorale for orchestra entitled 'Hirtengesang an der Krippe' the following subject plays an important part.

It is impossible to reduce this passage to any known rhythm; but when the first feeling of strangeness is past there is a peculiar and quaint charm about the music which no other combination would have produced. Such examples as those last quoted are however given merely as curiosities, and are in no way to be recommended as models for imitation.

Besides the alternation of various accents, it is also possible to combine them simultaneously. The following extract from the first finale of 'Don Giovanni' is not only one of the best-known but one of the most successful experiments in this direction.

![\version "2.14.2"

\header {

tagline = ##f }

\layout {

\context {

\Score

\remove "Timing_translator"

\remove "Default_bar_line_engraver"

}

\context {

\Staff

\consists "Timing_translator"

\consists "Default_bar_line_engraver"

}

}

% Now each staff has its own time signature.

\score { \relative g'' <<

\new Staff {

\time 2/8

\set Staff.timeSignatureFraction = #'(3 . 8)

\key g \major

\mark \markup \small "27."

\repeat unfold 3 { \grace fis16 g4.*2/3 } g16*2/3[( a b a g8*2/3])

b,16*2/3[( c d c b8*2/3]) r8*2/3 b( g) fis( a) a-. a( c) c-.

c( fis) fis-. a[( a16*2/3 b c a]) g4*2/3( b8*2/3)

}

\new Staff {

\time 2/4 \key g \major \partial 4

\grace s16 d8 b | g4 g8 g | g( d) d-. d-. |

d( b) c-. a-. | fis-. a-. d, e16 fis | g4 g'8 g

}

\new Staff {

\time 3/4 \key g \major \override Staff.Rest #'style = #'classical

\grace s16 d4 d8 d d d | d8.( g16) d4 r |

c4 c8 c c c | \grace d16 c8( b16 c) b4

}

>>

\midi { }

\layout { } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/h/dhfpe0i3z5qltb0dxrstmn5bhoodx87/dhfpe0i3.png)

In the above quotation the first line gives a quick waltz in 3-8 time with only one accent in the bar, this accent falling with each beat of the second and third lines. The contredanse in 2-4 time and the minuet in 3-4 have each two accents in the bar, a strong and a weak one, as explained above. The crotchet being of the same length in both, it will be seen that the strong accents only occur at the same time in both parts on every sixth beat, at every second bar of the minuet, and at each third bar of the contredanse. A somewhat similar combination of different accents will be found in the slow movement of Spohr's symphony 'Die Weihe der Töne.'

All the accents hitherto noticed belong to the class called by some writers on music grammatical or metrical; and are more or less inherent in the very nature of music. There is however another point of view from which accent may be regarded—that which is sometimes called the oratorical accent. By this is meant the adaptation in vocal music of the notes to the words, of the sound to the sense. We are not speaking here of the giving a suitable expression to the text; because though this must in some measure depend upon the accent, it is only in a secondary degree connected with it. What is intended is rather the making the accents of the music correspond with those of the words. A single example will make this clear. The following phrase

![{ \time 6/8 \key aes \major \partial 8 \mark \markup \small "28." \relative e' { ees8 | c'4 c8 c([ bes)] g | aes4. ees4 r8 | s8 }

\addlyrics { Oh love -- ly fish -- er -- maid -- en! } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/0/i0dxeqf3nmwgabysknjdhq2lczar875/i0dxeqf3.png)

is the commencement of a well-known song from the 'Schwanengesang' by Schubert. The line contains seven syllables, but it is evident that it is not every line of the same length to which the music could be adapted. For instance, if we try to sing to the same phrase the words 'Swiftly from the mountain's brow,' which contain exactly the same number of syllables, it will be found impossible, because the accented syllables of the text will come on the unaccented notes of the music, and vice versa. Such mistakes as these are of course never to be found in good music, yet even the greatest composers are sometimes not sufficiently attentive to the accentuation of the words which they set to music. For instance, in the following passage from 'Freischütz,' Weber has, by means of syncopation and a sforzando, thrown a strong accent on the second syllable of the words 'Augen,' 'taugen,' and 'holden,' all of which (as those who know German will be aware) are accented on the first syllable.

![{ \time 6/8 \key ees \major \partial 4 \mark \markup \small "29." \relative g' { \autoBeamOff g8 aes | bes([ g)] ees'-> ~ ees c16([ d)] ees([ f)] | g8([ bes,)] ees-> ~ ees f16([ ees)] d([ c)] | bes8([ f)] bes-> ~ bes a16([ bes)] c([ bes)] | g4 r8 } \addlyrics { Trü -- be Au -- gen, Lieb -- chen, tau -- gen ei -- nem hol -- den Bräut -- chen nicht. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/k/bke2g1jcgmya9josdy25s3wxdohm7dv/bke2g1jc.png)

[First two notes of bars 2 & 3 amended per correction given in App. p.517]

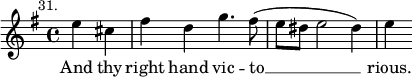

Ths charm of the music makes the hearer overlook the absurdity of the mispronunciation; but it none the less exists, and is referred to not in depreciation of Weber, but as by no means a solitary instance of the want of attention which even the greatest masters have sometimes given to this point. Two short examples of a somewhat similar character are here given from Handel's 'Messiah' and 'Deborah.'

In the former of these extracts the accent on the second syllable of the word 'chastisement' may not improbably have been caused by Handel's imperfect acquaintance with our language; but in the chorus from 'Deborah,' in which the pronunciation of the last word according to the musical accents will be vīctŏriōus, it is simply the result of indifference or inattention, as is shown by the fact that in other parts of the same piece the word is set correctly.

Closely connected with the present subject, and therefore appropriately to be treated here, is that of Inflexion. Just as in speaking we not only accent certain words, but raise the voice in uttering them, so in vocal music, especially in that depicting emotion, the rising and falling of the melody should correspond as far as possible to the rising and falling of the voice in the correct and intelligent reading of the text. It is particularly in the setting of recitative that opportunity is afforded for this, and such well-known examples as Handel's 'Thy rebuke hath broken his heart' in the 'Messiah,' or 'Deeper and deeper still' in 'Jephtha,' or the great recitative of Donna Anna in the first act of 'Don Giovanni' may be studied with advantage by those who would learn how inflexion may be combined with accent as a means of musical expression. But, though peculiarly adapted to recitative, it is also frequently met with in songs. Two extracts from Schubert are here given. In asking a question we naturally raise the voice at the end of the sentence; and the following quotation will furnish an example of what may be called the interrogatory accent.

32. Schubert, 'Schöne Müllerin,' No. 8.

![{ \time 3/4 \partial 8 \relative d'' { \autoBeamOff d8 | d4. d8 d d | cis8. e16 e4. a,16([ b)] | c4. c8 c c | b8. d16 d4.\fermata } \addlyrics { Ver -- driesst dich denn mein Gruss so schwer? Ver -- stört dich denn mein Blick so sehr? } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/e/me7jtqrf0ohfm6rx4nkw3b6yojj0jh1/me7jtqrf.png)

The passage next to be quoted illustrates what may rather be termed the declamatory accent.

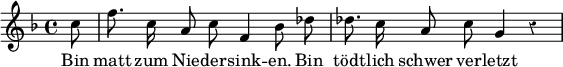

33. 'Winterreise,' No. 21.

The word 'matt' is here the emphatic word of the line; but the truthful expression of the music is the result less of its being set on the accented part of the bar than of the rising inflexion upon the word, which gives it the character of a cry of anguish. That this is the case will be seen at once if C is substituted for F. The accent is unchanged, but all the force of the passage is gone.

What has just been said leads naturally to the last point on which it is needful to touch—the great importance of attention to the accents and inflexions in translating the words of vocal music from one language to another. It is generally difficult, often quite impossible, to preserve them entirely; and this is the reason why no good music can ever produce its full effect when sung in a language other than that to which it was composed. Perhaps few better translations exist than that of the German text to which, Mendelssohn composed his 'Elijah'; yet even here passages may be quoted in which the composer's meaning is unavoidably sacrificed, as for example the following—

Here the different construction of the English and German languages made it impossible to preserve in the translation the emphasis on the word 'mich' at the beginning of the second bar. The adapter was forced to substitute another accented word, and he has done so with much tact; but the exact force of Mendelssohn's idea is lost. In this and many similar cases all that is possible is an approximation to the composer's idea; the more nearly this can be attained, the less the music will suffer.