A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Accompaniment

ACCOMPANIMENT. This term is applied to any subsidiary part or parts, whether vocal or instrumental, that are added to a melody, or to a musical composition in a greater number of parts, with a view to the enrichment of its general effect; and also, in the case of vocal compositions, to support and sustain the voices.

An accompaniment may be either 'Ad libitum' or 'Obligato.' It is said to be Ad libitum when, although capable of increasing the relief and variety, it is yet not essential to the complete rendering of the music. It is said to be Obligato when, on the contrary, it forms an integral part of the composition.

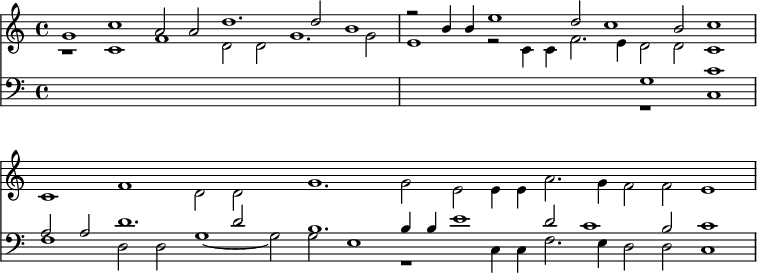

Among the earliest specimens of instrumental accompaniment that have descended to us, may be mentioned the organ parts to some of the services and anthems by English composers of the middle of the 16th century. These consist for the most part of a condensation of the voice parts into two staves; forming what would now be termed a 'short score.' These therefore are Ad libitum accompaniments. The following are the opening bars of 'Rejoyce in the Lorde allwayes,' by John Bedford (about 1543):—

Before speaking of Obligato accompaniment it is necessary to notice the remarkable instrumental versions of some of the early church services and anthems, as those by Tallis, Gibbons, Amner, etc. which are still to be met with in some of the old organ and other MS. music books. These versions are so full of runs, trills, beats, and matters of that kind, and are so opposed in feeling to the quiet solidity and sober dignity of the vocal parts, that even if written by the same hand, which is scarcely credible, it is impossible that the former can ever have been designed to be used as an accompaniment to the latter. For example, the instrumental passage corresponding with the vocal setting of the words 'Thine honourable, true, and only Son,' in the Te Deum of Tallis (died 1585) stands thus in the old copies in question:—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 16/8 << { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"church organ" \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 120 \clef treble << \relative g' { g2 c ~ c8[ b c a] b[ a b gis] | a[ gis a fis] gis[ fis gis e] c'[ b c a] b[ a b gis] } \\ \relative e' { e2 e1 e2 | e e e e } >> | a'2. a'4 gis'1 | }

\new Staff { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"church organ" \clef bass << \relative b { b2 a1 gis2 | c8[ b c a] b[ a b gis] a[ gis a fis] gis[ fis gis e] } \\ \relative e { e2 a,1 e'2 | c e a, e' } >> | \relative c { c8[ b c gis] a[ e c a] e'1^\markup { \raise #2 \smaller etc. } } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/a/pakyloplhgdtd28xpz5wy2ysh6uc15w/pakylopl.png)

while that of the phrase to the words 'The noble army of martyrs praise Thee,' in the well-known Te Deum in F of Gibbons (1583–1625), appears in this shape:—

The headings or 'Indexing' of these versions stand as follows, and are very suggestive:—'Tallis in D, organ part varied'; 'Te Deum, Mr. Tallis, with Variations for the Organ'; 'Gibbons in F, Morning, with Variations'; 'Te Deum, Mr. Orlando Gibbons, in F fa ut, varied for the Organ'; and so forth. There is little doubt therefore that the versions under notice were not intended as accompaniments at all, but were variations or adaptations like the popular 'Transcriptions' of the present day, and made for separate use, that use being doubtless as voluntaries. This explanation of the matter receives confirmation from the fact that a second old and more legitimate organ part of those services is also extant, for which no ostensible use would have existed, if not to accompany the voices. Compare the following extract from Gibbons's Te Deum ('The noble army of Martyrs') with the preceding.

An early specimen of a short piece of 'obligato' organ accompaniment is presented by the opening phrase of Orlando Gibbons's Te Deum in D minor, which appears as follows:—

The early organ parts contained very few if any directions as to the amount of organ tone to be used by way of accompaniment. Indeed the organs were not capable of affording much variety. Even the most complete instruments of Tallis's time, and for nearly a century afterwards, seem to have consisted only of a very limited 'choir' and 'great' organs, sometimes also called 'little' and 'great' from the comparative size of the external separate cases that enclosed them; and occasionally 'soft,' as in the preceding extract, and 'loud' organs in reference to the comparative strength of their tone.

Other instruments were used besides the organ in the accompaniment of church music. Dr. Rimbault, in the introduction to 'A Collection of Anthems by Composers of the Madrigalian Era,' edited by him for the Musical Antiquarian Society in 1845, distinctly states that 'all verse or solo anthems anterior to the Restoration were accompanied with viols, the organ being only used in the full parts;' and the contents of the volume consist entirely of anthems that illustrate how this was done. From the first anthem in that collection, 'Blow out the trumpet,' by M. Este (about 1600), the following example is taken—the five lower staves being instruments:—

The resources for varied organ accompaniment were somewhat extended in the 17th century through the introduction, by Father Smith and Renatus Harris, of a few stops, until then unknown in this country; and also by the insertion of an additional short manual organ called the Echo; but no details have descended to us as to whether these new acquisitions were turned to much account. The organ accompaniments had in fact ceased to be written with the former fullness, and had gradually assumed simply an outline form. That result was the consequence of the discovery and gradual introduction of a system by which the harmonies were indicated by means of figures, a short-hand method of writing which afterwards became well known by the name of Thorough Bass. The 'short-score' accompaniments—which had previously been generally written, and the counterparts of which are now invariably inserted beneath the vocal scores of the modern reprints of the old full services and anthems—were discontinued; and the scores of all choral movements published during the 18th and the commencement of the present century, were for the most part furnished with a figured bass only by way of written accompaniment. The custom of indicating the harmonies of the accompaniment in outline, and leaving the performer to interpret them in any of the many various ways of which they were susceptible, was followed in secular music as well as in sacred; and was observed at least from the date of the publication of Purcell's 'Orpheus Britannicus,' in 1697 [App. p.517 "1698"], down to the time of the production of the English ballad operas towards the latter part of the last century.

In committing to paper the accompaniments to the 'solos' and 'verses' of the anthems written during the period just indicated, a figured bass was generally all that was associated with the voice part; but in the symphonies or 'ritornels' a treble part was not unfrequently supplied, usually in single notes only, for the right hand, and a figured bass for the left. Occasionally also a direction was given for the use of a particular organ register, or a combination of them; as 'cornet stop,' 'bassoon stop,' 'trumpet or hautboy stop,' 'two diapasons, left hand,' 'stop diapason and flute'; and in a few instances the particular manual to be used was named, as 'eccho,' 'swelling organ,' etc.

Although the English organs had been so much improved in the volume and variety of their tone that the employment of other instruments gradually fell into disuse, yet even the best of them were far from being in a state of convenient completeness. Until nearly the end of the 18th century English organs were without pedals of any kind, and when these were added they were for fifty years made to the wrong compass. There was no independent pedal organ worthy of the name; no sixteen-feet stops on the manuals; the swell was of incomplete range; and mechanical means, in the shape of composition-pedals for changing the combination of stops were almost entirely unknown; so that the means for giving a good instrumental rendering of the suggested accompaniments to the English anthems really only dates back about thirty years.

The best mode of accompanying a single voice in compositions of the kind under consideration was fully illustrated by Handel in the slightly instrumented songs of his oratorios, combined with his own way of reducing his thorough-bass figuring of the same into musical sounds. Most musical readers will readily recall many songs so scored. The tradition as to Handel's method of supplying the intermediate harmonies has been handed down to our own time in the following way. The late Sir George Smart, at the time of the Handel festival in Westminster Abbey in 1784, was a youthful chorister of the Chapel Royal of eight years of age; and it fell to his lot to turn over the leaves of the scores of the music for Joah Bates, who, besides officiating as conductor, presided at the organ. In the songs Bates frequently supplied chords of two or three notes from the figures on a soft-toned unison stop. The boy looked first at the book, then at the conductor's fingers, and seemed somewhat puzzled, which being perceived by Bates, he said, 'my little fellow, you seem rather curious to discover my authority for the chords I have just been playing;' to which observation young Smart cautiously replied, 'well, I don't see the notes in the score;' whereupon Mr. Bates added, 'very true, but Handel himself used constantly to supply the harmonies in precisely the same way I have just been doing, as I have myself frequently witnessed.'

Acting on this tradition, received from the lips of the late Sir George Smart, the writer of the present article, when presiding occasionally, for many years, at the organ at the concerts given by Mr. Hullah's Upper Singing Schools in St. Martin's Hall, frequently supplied a few simple inner parts; and as in after conversations with Mr. Hullah as well as with some of the leading instrumental artists of the orchestra, he learnt that the effect was good, he was led to conclude that such insertions were in accordance with Handel's intention. Acting on this conviction he frequently applied Handel's perfect manner of accompanying a sacred song, to anthem solos; for its exact representation was quite practicable on most new or modernised English organs. Of this fact one short illustration must suffice. The introductory symphony to the alto solo by Dr. Boyce (1710–1779) to the words beginning 'One thing have I desired of the Lord' is, in the original, written in two parts only, namely, a solo for the right hand, and a moving bass in single notes for the left; no harmony being, given, nor even figures denoting any. By taking the melody on a solo stop, the bass on the pedals (sixteen feet) with the manual (eight feet) coupled, giving the bass in octaves, to represent the orchestral violoncellos and double basses, the left hand is left at liberty to supply inner harmony parts. These latter are printed in small notes in the next and all following examples. In this manner a well-balanced and complete effect is secured, such as was not possible on any organ in England in Dr. Boyce's own day.

Notice may here be taken of a custom that has prevailed for many years in the manner of supplying the indicated harmonies to many of Handel's recitatives. Handel recognised two wholly distinct methods of sustaining the voice in such pieces. Sometimes he supported it by means of an accompaniment chiefly for bow instruments; while at other times he provided only a skeleton score, as already described. In the four connected recitatives in the 'Messiah,' beginning with 'There were shepherds,' Handel alternated the two manners, employing each twice; and Bach, in his 'Matthew Passion Music,' makes the same distinction between the ordinary recitatives and those of our Lord. It became the custom in England in the early part of the present century to play the harmonies of the figured recitatives not on a keyed instrument, but on a violoncello. When or under what circumstances the substitution was made, it is not easy now to ascertain; but if it was part of Handel's design to treat the tone-quality of the smaller bow instruments as one of his sources of relief and musical contrast, as seems to have been the case, the use of a deeper toned instrument of the same kind in lieu of the organ would seem rather to have interfered with that design. It is not improbable that the custom may have taken its rise at some provincial music meeting, where either there was no organ, or where the organist was not acquainted with the traditionary manner of accompanying; and that some expert violoncellist in the orchestra at the time supplied the harmonies in the way that afterwards became the customary manner.

But to continue our notice of the accompaniments to the old anthem music. A prevalent custom with the 18th-century composers was to write, by way of introductory symphony, a bass part of marked character, with a direction to the effect that it was to be played on the 'loud organ, two diapasons, left hand'; and to indicate by figures a right-hand part, to be played on the 'soft organ,' of course in close harmony. By playing such a bass on the pedals (sixteen feet) with the great manual coupled thereto, not only is the bass part enriched by being played in octaves, but the two hands are left free for the interpretation of the figures in fuller and more extended harmony. The following example of this form of accompaniment occurs as the commencement of the bass solo to the words "Thou art about my path and about my bed, ' by Dr. Croft (1677 to 1727).

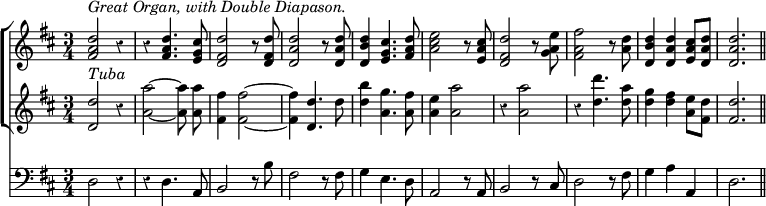

Sometimes the symphony to a solo, if of an arioso character, can be very agreeably given out on a combination of stops, sounding the unison, octave, and sub-octave, of the notes played, as the stopped diapason, flute, and bourdon on the great organ; the pedal bass, as before consisting of a light toned sixteen feet stop with the manual coupled. Dr. Greene's (died 1755) alto solo to the words 'Among the gods there is none like Thee, O Lord,' is in a style that affords a favourable opportunity for this kind of organ treatment.

![{ \time 4/4

<< \new ChoirStaff << \new Staff { \clef treble \key ees \major \relative e''

<< { ees4.^\markup { \italic "Gt. Organ, Bourdon, Stopped Diapason and Flute." } bes8 ees[ g16. f32] ees8[ d] |

c c[ d ees] f2 ~ | f8[ bes16. d,32] ees8[ f]\trill g2 ~ |

g8[ c16. e,32] f8[ g]\trill aes2 ~ | aes8[ g16 f] aes[ g f ees] d8[ ees16 c] ees8[ d] | ees4 }

\\

{ g,8[ bes16. aes32] g8[ f] g2 | aes8[ c16. bes32] aes8[ g] f a] bes c_\trill] |

d[ bes] ~ bes4 bes8 b[ c d] | ees[ c] ~ c4 ~ c8[ f16. ees32] d8_\turn[ ees16 c] |

bes4. c8 bes[ c bes aes] | g4 }

>> }

\new Staff { \clef treble \key ees \major \relative b

{ bes4. f'8 ees2 ~ | ees4 f8[ bes,] ~ bes c[ d <ees a>] |

<< \relative b' { bes d,16.[ f32] ees8[ <aes d,>] <g ees> d[ ees f]\trill |

ees[ e16. g32] f8[ <bes ees,>] <aes f>[ c16. bes32] aes8[ g] | }

\\

{ bes'8 bes, ~ bes4 ~ bes8 d[ c b] | c2 ~ c4 s | }

>> f8[ d ees c] f[ aes g <f bes,>] | <ees bes>4 } }

>>

\new Staff { \clef bass \key ees \major \relative e

{ ees8[_\markup { \italic "Pedal 16 ft., with Great Organ coupled." } g16. f32] ees8[ d] c[ ees16. d32] c8[ bes] |

aes[ aes'16. g32] f8[ ees] d[ f16. ees32] d8[ c] | bes[ bes'16. aes32] g8[ f] ees[ g16. f32] ees8[ d] |

c[ c'16. bes32] aes8[ g] f[ aes16. g32] f8[ ees] | d[ bes ees aes] bes[ aes bes bes,] | ees4 }

}

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/8/q8mjmzaymyuc32p3lijaps978uhp0ry/q8mjmzay.png)

The foregoing examples illustrate the manner in which English anthem solos and their symphonies, presenting as they do such varied outline, may be accompanied and filled up. But in the choral parts of anthems equally appropriate instrumental effects can also frequently be introduced, by reason of the improvements that have been made in English organs within the last thirty years. The introduction of the tuba on a fourth manual has been an accession of great importance in this respect. Take for illustration the chorus by Kent (1700–1776), 'Thou, O Lord, art our Father, our Redeemer,' the climax of which is, in the original, rather awkwardly broken up into short fragmentary portions by rests, but which can now be appropriately and advantageously united by a few intermediate jubilant notes in some such manner as the following—:

Again, in Dr. Greene's anthem, 'God is our hope and strength,' occurs a short chorus, 'O behold the works of the Lord,' which, after a short trio, is repeated, in precisely the same form as that in which it previously appears. According to the modern rules of musical construction and development it would be considered desirable to add some fresh feature on the repetition, to enhance the effect. This can now be supplied in this way, or in some other analogous to it.

The organ part to Dr. Arnold's collection of Cathedral Music, published in 1790, consists chiefly of treble and bass, with figures; so does that to the Cathedral Music of Dr. Dupuis, printed a few years later. Vincent Novello's organ part to Dr. Boyce's Cathedral Music, issued about five-and-twenty years ago, on the contrary, was arranged almost as exclusively in 'short score.' Thus after a period of three centuries, and after experiment and much experience, organ accompaniments, in the case of full choral pieces, came to be written down on precisely the same principle on which they were prepared at the commencement of that period.

Illustrations showing the way of interpreting figured basses could be continued to almost any extent, but those already given will probably be sufficient to indicate what may be done in the way of accompaniment, when the organ will permit, and when the effects of the modern orchestra are allowed to exercise some influence.

Chants frequently offer much opportunity for variety and relief in the way of accompaniment. The so-called Gregorian chants being originally written without harmony—at any rate in the modern acceptation of the term—the accompanyist is left at liberty to supply such as his taste and musical resources suggest. The English chants, on the other hand, were written with vocal harmony from the first; and to them much agreeable change can be imparted either by altering the position of the harmonies, or by forming fresh melodic figures on the original harmonic progressions. When sung in unison, as is now not unfrequently the case, wholly fresh harmonies can be supplied to the English chants, as in the case of the Gregorian. Treated in this manner they are as susceptible of great variety and agreeable contrast as are the older chants.

In accompanying English psalm tunes it is usual to make use of somewhat fuller harmony than that which is represented by the four written voice-parts. The rules of musical composition, as well as one's own musical instinct, frequently require that certain notes, when combined with others in a particular manner, should be followed by others in certain fixed progressions; and these progressions, so natural and good in themselves, occasionally lead to a succeeding chord or chords being presented in 'incomplete harmony' in the four vocal parts. In such cases it is the custom for the accompanyist to supply the omitted elements of the harmony; a process known by the term 'filling in.' Mendelssohn's Organ Sonatas, Nos. 5 and 6, each of which opens with a chorale, afford good examples of how the usual parts may be supplemented with advantage. The incomplete harmonies are to be met with most frequently in the last one or two chords of the clauses of a tune; the omitted note being generally the interval of a fifth above the bass note of the last chord; which harmony note, as essential to its correct introduction, sometimes requires the octave to the preceding bass note to be introduced, as at the end of the third clause of the example below; or to be retained if already present, as at the end of the fourth clause. An accompaniment which is to direct and sustain the voices of a congregation should be marked and decided in character, without being disjointed or broken. This combination of distinctness with continuity is greatly influenced by the manner in which the repetition notes are treated. Repetition notes appear with greater or less frequency in one or other of the vocal parts of nearly all psalm tunes, as exhibited in the example below. Those that occur in the melody should not be combined, but on the contrary should generally speaking be repeated with great distinctness. As such notes present no melodic movement, but only rhythmic progress, congregations have on that account a tendency to wait to hear the step from a note to its iteration announced before they proceed; so that if the repetition note be not clearly defined, hesitation among the voices is apt to arise, and the strict time is lost. The following example will sound very tame and undecided if all the repetition notes at the commencement of the first and second clauses be held on.

A very little will suffice to steady and connect the organ tone; a single note frequently being sufficient for the purpose, and that even in an inner part, as indicated by the binds in the following example. A repetition note in the bass part may freely be iterated on the pedal, particularly if there should be a tendency among the voices to drag or proceed with indecision.

Old Hundredth tune.