A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Clarinet

CLARINET or CLARIONET (Fr. Clarinette, Ger. Klarinette, Ital. Clarinetto). An instrument of 4-foot tone, with a single reed and smooth quality, commonly said to have been invented about the year 1690, by Johann Christopher Denner, at Nuremberg. Mr. W. Chappell is however of opinion that he can trace the instrument back to mediæval times as the shawm, schalm, or schalmuse (Hist, of Music, i. 264).

The present name, in both forms, is evidently a diminutive of Clarino, the Italian for trumpet, and Clarion the English equivalent, to which its tone has some similarity.

Since its first invention it has been successively improved by Stadler of Vienna, Iwan Muller, Klosé, and others. The last-named musician (1843) completely reorganised the fingering of the instrument, on the system commonly called after Boehm, which is also applied to the flute, oboe, and bassoon. A general description of the older and more usual form will be given. It may however be remarked here, that Boehm or Klosé's fingering is hardly so well adapted to this as to the octave scaled instruments. It certainly removes some difficulties, but at the expense of greatly increased complication of mechanism, and liability to get out of order.

The clarinet consists essentially of a mouth-piece furnished with a single beating reed, a cylindrical tube, terminating in a bell, and eighteen openings in the side, half closed by the fingers, and half by keys. The fundamental scale comprises nineteen semitones, from E in the bass stave.

The mouthpiece is a conical stopper, flattened on one side to form the table for the reed, and thinned to a chisel edge on the other for convenience to the lips. The cylindrical bore passes about two-thirds up the inside, and there terminates in a hemispherical end. From this bore a lateral orifice is cut into the table, about an inch long and half as wide, which is closed in playing by the thin end of the reed. The table on which the reed lies, instead of being flat, is purposely curved backwards towards the point, so as to leave a gap or slit about the thickness of a sixpence between the end of the mouthpiece and the point of the reed. It is on the vibration of the reed against this curved table that the sound of the instrument depends. The curve of the table is of considerable importance. [See Mouthpiece.] The reed itself is a thin flat slip cut from a kind of tall grass (arundo sativa), commonly, though incorrectly, termed 'cane.' [See Reed.] It is flattened on one side, and thinned on the other to a feather-edge. The older players secured this to the table of the mouthpiece by a waxed cord, but a double metallic band with two small screws, termed a ligature, is now employed. The reed was originally turned upwards, so as to rest against the upper lip; but this necessitated the holding of the instrument at a large ungraceful angle from the body, and caused it to bear against a weaker mass of muscles than is the case when it is directed downwards. In England, France, and Belgium it is always held in the latter position.

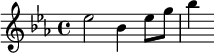

The compass given above is that of an instrument in C, which sounds corresponding notes to the violin, descending three semitones below 'fiddle G.' But the C clarinet is not very extensively used in the orchestra or military bands. The latter employ an instrument in B♭, sounding two semitones below its written position, and consequently standing in the key of two flats. For the acuter notes they use a smaller clarinet in E♭, which sounds a minor third above its written scale, and stands in three flats. In the orchestra an instrument in A, sounding a minor third below the corresponding note of a C instrument, is much used, and stands in three sharps. It will be seen that the B♭ and A clarinets respectively lower the range of the lowest note to D♮ and C♯, thus augmenting the whole compass of the instrument.| 1. C clarinet |  |

| 2. B♭ " |  |

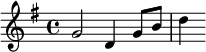

| 3. A " |  |

| 4. E♭ " |  |

| 5. F " |  |

| 6. For Corno di bassetto in F: |  |

Besides the four instruments already named others are occasionally used. A small clarinet in F, above the C instrument, has been mercifully given up, except in an occasional piece of German dance music. The D, between these two, is also considered by some composers to blend better with the violins than the graver-pitched clarinets. The D♭ is convenient for taking the part of the military flute, which stands in that key. A clarinet in H would puzzle most English players, although it appears in Mozart's score of 'Idomeneo'—being the German for B♮. Below the A clarinet we also have several others. One in A♭ is useful in military music. In F we have the tenor clarinet, and the corno di bassetto or bassethorn, perhaps the most beautiful of the whole family. The tenor in E♭ stands in the same relation to this as the B♭ does to the C, and is consequently used in military bands. [Corno di Bassetto.] Proceeding still lower in the scale we arrive at the bass clarinets. The commonest of these is in B♭, the octave of the ordinary instrument, but the writer has a C basso of Italian make, and Wagner has written for an A basso. They are none of them very satisfactory instruments; the characteristic tone of the clarinet seeming to end with the corno di bassetto. [See Bass Clarinet.]

Helmholtz has analysed the tone and musical character of the clarinet among the other wind-instruments, and shows that the sounds proper to the reed itself are hardly ever employed, being very sharp and of harsh quality; those actually produced being lower in pitch, dependent on the length of the column of air, and corresponding to the sounds proper to a stopped organ-pipe. With a cylindrical tube these are the third, fifth, seventh, and eighth partial sounds of the fundamental tone. The upper register rising a twelfth from the lower or chalumeau, seems to carry out the same law in another form. On the other hand, the conical tubes of the oboe and bassoon correspond to open pipes of the same length, in which the octave, the twelfth, and the double octave form the first three terms of the series. See his paper in the 'Journal für reine und angewandte Mathematik,' vol. Ivii.

The lowest note of the register is clearly an arbitrary matter. It has probably been dictated by the fact that nine of the ten available digits are fully occupied. But M. Sax, whose improvements in wind-instruments have surpassed those which explicitly bear his name, has extended the scale another semitone by adding a second key for the right little finger. Even the octave C can be touched by employing the right thumb, which at present merely supports the instrument. It is always so employed in the bassethorn, and a B♭ instrument thus extended must have been known to Mozart, who writes the beautiful obbligato to 'Parto,' in his 'Clemenza di Tito,' down to bass B♭, a major third below the instrument as now made.

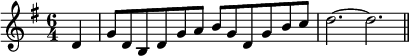

To whatever period we may ascribe the invention of the clarinet, it is certain that it does not figure in the scores of the earlier composers. Bach and Handel never use it. An instrument entitled Chalumeau appears in the writings of Gluck, to which Berlioz appends the note that it is now unknown and obsolete. This may have been a clarinet in some form. [App. p.591 adds that "the first instance of the use of the clarinet as an orchestral instrument is said to be in J. C. Bach's 'Orione' (1763)."] Haydn uses it very sparingly. Most of his symphonies are without the part, and the same remark applies to his church music. There is, however, a fine trio for two clarinets and bassoon in the 'Et Incarnatus' of the First Mass, and there are one or two prominent passages in the 'Creation,' especially obbligatos to the air 'With verdure clad,' and 'On mighty pens,' and a quartet of reeds accompanying the trio 'On Thee each living soul awaits.' But it is with Mozart that the instrument first becomes a leading orchestral voice. 'Ah, if we had but clarinets too!' says he: 'you cannot imagine the splendid effect of a symphony with flutes, oboes, and clarinets.' (Letter 119.) Nothing can be more beautiful, or more admirably adapted to its tone than the parts provided for it in his vocal and instrumental works. The symphony in E♭ is sometimes called the Clarinet Symphony from this reason, the oboes being omitted as if to ensure its prominence. There is a concerto for clarinet with full orchestra (Köchel, No. 622) which is in his best style. For the tenor clarinet or basset-horn, the opera of 'Clemenza di Tito' is freely scored, and an elaborate obbligato is allotted to it in the song 'Non più di fiori.' His 'Requiem' contains two corni di bassetto, to the exclusion of all other reed-instruments, except bassoons. His chamber and concerted music is more full for clarinets than that of any other writer, except perhaps Weber. It is somewhat remarkable that many of his great works, especially the ' Jupiter' Symphony, should be without parts for the instrument, notwithstanding his obvious knowledge of its value and beauty. The ordinary explanation is probably the true one; namely, that being attached to a small court, he seldom had at his disposal a full band of instrumentalists. Beethoven, on the other hand, hardly writes a single work without clarinets. Indeed there is a distinct development of this part to be observed in the course of his symphonies. The trio of the First contains a passage of importance, but of such simplicity that it might be allotted to the trumpet. The Larghetto (in A) of his Second Symphony is full of melodious and easy passages for two clarinets. It is not until we reach the 'Pastoral' Symphony that difficulties occur; the passage near the close of the first movement being singularly trying to the player:—

But the Eighth Symphony contains a passage in the Trio, combined with the horns, which few performers can execute with absolute correctness.

Beethoven does not seem to have appreciated the lower register of this instrument. All his writings lie in the upper part of its scale, and, except an occasional bit of pure accompaniment, there is nothing out of the compass of the violin.

Mendelssohn, on the other hand, seems to revel in the chalumeau notes. He leads off the Scotch Symphony, the introductory notes of 'Elijah,' and the grand chords of his overture to 'Ruy Blas' with these, and appears fully aware of the singular power and resonance which enables them to balance even the trombones. Throughout his works the parts for clarinet are fascinating, and generally not difficult. The lovely second subject in the overture to the 'Hebrides' (after the reprise)—

the imitative passage for two clarinets, which recurs several times in the Overture to 'Melusina'—

Weber appears to have had a peculiar love for the clarinet. Not only has he written several great works especially for it, but his orchestral compositions abound in figures of extreme beauty and novelty. The weird effect of the low notes in the overture to 'Der Freischütz,' followed by the passionate recitative which comes later in the same work—both of which recur in the opera itself—will suggest themselves to all; as will the cantabile phrase in the overture to 'Oberon,' the doubling of the low notes with the violoncellos, and the difficult arpeggios for flutes and clarinets commonly known as the 'drops of water.' His Mass in G is marked throughout by a very unusual employment of the clarinets on their lower notes, forming minor chords with the bassoons. This work is also singular in being written for B♭ clarinets, although in a sharp key. The 'Credo,' however, has a characteristic melody in a congenial key, where a bold leap of two octaves exhibits to advantage the large compass at the composer's disposal.

Meyerbeer and Spohr both employ the clarinets extensively. The former, however, owing to his friendship with Sax, was led to substitute the bass clarinets in some places. [Bass Clarinet.] Spohr has written two concertos for the instrument, both—especially the second—of extreme difficulty. But he has utilised its great powers in concerted music, and as an obbligato accompaniment to the voice, both in his operatic works and his oratorios, and in the six songs of which the 'Bird and the Maiden' is the best known.

An account of this instrument would be incomplete without mention of Rossini's writings. In the 'Stabat Mater' he has given it some exquisite and appropriate passages, but in other works the difficulties assigned to it are all but insuperable. The overtures to 'Semiramide,' 'Otello,' and 'Gazza Ladra,' are all exceedingly open to this objection, and exhibit the carelessness of scoring which mars his incomparable gifts of melody.

No instrument has a greater scope in the form of solo or concerted music specially written for it. Much of this is not so well known in this country as it ought to be. The writer has therefore compiled, with the assistance of Mr. Leonard Beddome, whose collection of clarinet music is all but complete, a list of the principal compositions by great writers, in which it takes a prominent part. This is appended to the present notice.

A few words are required in concluding, as to the weak points of the instrument. It is singularly susceptible to atmospheric changes, and rises in pitch very considerably, indeed more than any other instrument, with warmth. It is therefore essential, after playing some time, to flatten the instrument; a caution often neglected. On the other hand it does not bear large alterations of pitch without becoming out of tune. In this respect it is the most difficult of all the orchestral instruments, and for this reason it ought undoubtedly to exercise the privilege now granted by ancient usage to the oboe; that, namely, of giving the pitch to the band. In the band of the Crystal Palace, and some others, this is now done; it deserves general imitation. Moreover, the use of three, or at least two different-pitched instruments in the orchestra, is a source of discord, which it requires large experience to counteract. Many performers meet the difficulty to some extent by dispensing with the C clarinet, the weakest of the three. Composers would do well to write as little for it as may be practicable. Mendelssohn, in his Symphonies, prefers to write for the A clarinet in three flats rather than for the C in its natural key, thus gaining a lower compass and more fulness of tone. Lastly, the whole beauty of the instrument depends on the management of the reed. A player, however able, is very much at the mercy of this part of the mechanism. A bad reed not only takes all quality away, but exposes its possessor to the utterance of the horrible shriek termed couac (i.e. 'quack') by the French, and 'a goose' in the vernacular. There is no instrument in which failure of lip or deranged keys produce so unmusical a result, or one so impossible to conceal; and proportionate care should be exercised in its prevention.

List of the principal solo and concerted music for the clarinet; original works, not arrangements.

Mozart.—Trio for clarinet, viola, and piano, op. 14; Two Serenades for two oboes, two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons, op. 24 and 27; Quintet for oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, and piano, op. 29; Concerto for clarinet and orchestra, op. 107; Quintet for clarinet and strings, op. 101; Grand Serenade for two oboes, two clarinets, two bassethorns, two French horns, two bassoons and double bassoon.

Beethoven.—Three duets for clarinet and bassoon; Trio for clarinet, violoncello, and piano, op. 11; Quintet for oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, and piano, op. 16; Grand Septet for violin, viola, cello, contra-basso, clarinet, horn, and bassoon, op. 20; the same arranged by composer as trio for clarinet, cello, and piano; Sestet for two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons, op. 71; Ottet for two oboes, two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons, op. 103; Rondino for two oboes, two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons.

Weber.—Concertino, op. 26; Air and Variation, op. 33; Quintet for clarinet and string quartet, op. 34; Concertante duet, clarinet and piano, op. 48; Concerto 1, with orchestra, op. 73; Concerto 2, with orchestra, op. 74.

Spohr.—Concerto 1, for clarinet and orchestra, op. 26; Concerto 2, for clarinet and orchestra, op. 57; Nonet for strings, flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon, op. 31; Ottet for violin, two violas, cello, basso, clarinet, and two horns, op. 32; Quintet for flute, clarinet, horn, bassoon, and piano, op. 52; Septet for piano, violin, cello, and same wind, op. 147; Six songs, with clarinet obbligato, op. 103.

Schumann.—Fantasiestucke for clarinet and piano, op. 73; Mährchenerzählungen, for clarinet, viola, and piano, op. 132.

Onslow.—Septet for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, double bass, and piano, op. 79; Nonet, for strings, flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon, op. 77; Sestet for piano, flute, clarinet, horn, bassoon, and double bass, op. 30.

Kalliwoda.—Variations with orchestra, op. 128.

A. Romberg.—Quintet for clarinet and strings, op. 57.

Hummel.—Military Septet, op. 114.

C. Kreutzer.—Trio for piano, clarinet, and bassoon, op. 43; Septet, for violin, viola, cello, contra-basso, clarinet, horn, and bassoon, op. 62.

S. Neukomm.—Quintet for clarinet and strings, op. 8.

A. Reicha.—Quintet for clarinet and strings; Twenty-four quintets for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon, ops. 88–91, 99, 100.

E. Pauer.—Quintet for piano, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon, op. 44.

Reissiger.—Concertos, ops. 63a, 14b, 180.

- ↑ Berlioz rather unnecessarily makes four registers, treating Chalumeau as the second.