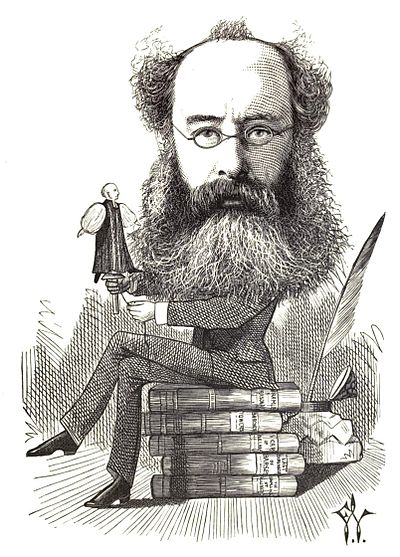

Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day/Anthony Trollope

ANTHONY TROLLOPE.

The name of Trollope was as familiar to the last generation of readers as it is to the present. Mrs. Fanny Trollope—she married in 1809 Anthony Trollope, barrister-at-law—having lost her husband, applied herself to literature. In 1832, the year of the Reform Bill in England, she published her first book. It was about the United States, where she had lived for some time, and was called 'Domestic Life of the Americans.'

In England, it was read and enjoyed. In the States, the people did not like it—they did not appear to advantage in the book; but it made the reputation of the lady who had written it; and Mrs. Fanny Trollope continued to apply herself to the manufacture of interesting and clever books, her chef-d'œuvre being 'The Widow Barnaby.' The authoress died at Florence in 1863; and in the outskirts of that city her eldest son, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, has made his home.

Her second son, the subject of this notice, has made England his home, and the English people his study.

Anthony Trollope seems to have 'thrown back' one generation. His grandfather was a parson; and it is in delineating the phases of clerical life, from the bishop to the curate, that this popular writer excels. Bishop Proudie, Archdeacon Grantley, the Rev. Obadiah Slope, Mr. Crawley of Hogglestock, are creations of his genius that have their originals in life. They are photographic portraits of men his readers know: nature clothed with the form of art: and from this exquisite truthfulness they derive their interest.

The conversations of the characters in his books are exactly the dialogues one hears in everyday life. One man turns to Trollope for his recreation, because 'it is exactly like life, you know.' Another man says: 'When I pick up a novel, I want to be taken above everyday life. I want the ideal. I don't find this in Trollope.' And so he does not read Trollope's

TO PARSONS GAVE UP, WHAT WAS MEANT FOR MANKIND.

books. These readers are types: the realist loving reality, which he finds; the idealist seeking for the noble, unselfish, poetic, which he does not find. Trollope's point of view is real and perfectly natural, but it is low.

His parsons, whether they are bishops, prebendaries, deans, vicars, or curates, are, as a rule, the selfish men of everyday life. Their wives are more worldly and selfish than they. What, then, is the mission of the novelist to educate or to depict? The numerous readers of the popular author must answer this.

Literary fame is a thing of slow growth, generally. Anthony Trollope began with a story, historical and dull, entitled 'La Vendee,' published by Colburn in 1850. He had missed his mark, but he soon rectified the mistake. In 1855 he published 'The Warden,' being the history of the Rev. Septimus Harding, warden of Hiram's Hospital, in the city of Barchester. Two years later, 'Barchester Towers' appeared; in 1858, 'Dr. Thorne,' another story of churchmen; and in the same year, 'The Three Clerks,' a story of legal and political life. In 1859, the prolific pen of the author furnished Mudie's subscribers with 'The Bertrams,' and an Irish story, 'The Kellys and the O'Kellys.' In the next year (1860), 'Castle Richmond' made its appearance; and then Thackeray invited Mr. Trollope to open the ball in 'The Cornhill' with a new story. This story, 'Framley Parsonage,' is one of his best productions. It is a charming piece of genre painting in ink, and did its part in maintaining his reputation, if it did not add anything to it. 'Orley Farm' (1862), 'Rachel Ray' (1863), 'The Small House at Allington,' and 'Can you forgive her?' followed in 1864, almost together; 'Miss Mackenzie' in '65, and 'The Belton Estate' in '66. In '67, 'The Last Chronicle of Barset,' and 'The Claverings;' in '69, 'He knew he was right,' and 'Phineas Finn.' 'The Vicar of Bulhampton,' 'Sir Harry Hotspur of Humblethwaite,' 'Ralph the Heir,' and 'The Golden Lion of Granpere,' close the list.

What other novelist has written as many stories of even merit? They are all below the high mark of the great writers; but all are interesting, all show good sound art in their manipulation. They represent a great total of work conscientiously performed. It seems well, in these fast times, to keep the ball rolling. Mrs. Henry Wood, Miss Braddon, and Anthony Trollope have laid this truth to heart. They have all of them a public, and they always take care to provide amusement for their readers. Something of theirs is always 'going on somewhere.'

This policy is sound. Fashions and tastes change, new writers may spring up, or old ones wear out. They charm while they may, while their 'copy' has a market value, and act on that most excellent proverb of making their hay while the sun shines. It is well that they should do so; and nobody's hay, old or new, is sweeter in the mouth than that of the writer whose books we have named. He is an artist who goes to nature for his materials; whose puppets are flesh and blood, not clothes-horses; and against whom the only fault we have to bring is, that he has. perhaps, too much 'to parsons given up what was meant for mankind.'