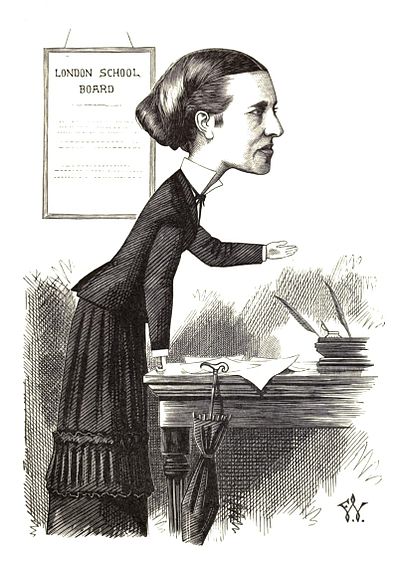

Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day/Dr. Garrett Anderson

DR. GARRETT ANDERSON.

In the middle ages, the work of women was clearly defined and unmistakable. If they were of the lower class, they made the clothes, spun the linen, kept the house; if of the higher, they received the guests, they embroidered, they presided at tournaments, and they were the family doctors. They knew the virtues of those simple herbs which they gathered in the garden and the fields; from these they concocted plasters and poultices for bruises and hurts, which must have been common enough in those days. Nicolette, in the old French novel, handles Aucassin's shoulder till she gets the joint into its proper place again, when she applies a poultice of soothing herbs. For medical purposes—perhaps also for a secret means of warming their hearts when they grew old—they brewed strong waters out of many a flower and fruit. All the winter long—when there was little fighting, and therefore few disorders, save those due to too much or too little feeding—they stayed in the castle and studied the art of healing. With the spring came dances, hawking, garland-making, sitting in the sunshine and under the shade, while the minstrels sang them ditties, and the knights made love, and preparations were made for the next tournament.

Here, it seems, was a fair and equitable distribution of labour. Both man and woman had to work. Why not? Man fought, tilled, traded. Women spun, kept house, and healed. Surgical operations, if any were required, were conducted in the handiest and simplest method possible—with the axe; as when Leopold of Austria had his leg amputated at a single blow, and died from loss of blood.

There came a time when the art of healing passed into men's hands. Then women had one occupation the less. They made up for this at first by becoming scholars. Everybody knows about the scholarship of Lady Jane Grey and Queen Elizabeth. The ladies of the sixteenth century read

M.D.

everything and knew everything. Then, too, under the auspices of Madame de Rambouillet, was born modern society. Learning went out of fashion as social amusements developed. Then women substituted play for work, and made amusement their occupation. The arts of house-wifery vanished with that of healing. The occupations of embroidery and spinning disappeared with that of study. In the eighteenth century, woman was either a fine lady or a household servant. If the former, she gambled, dressed, received, and went out; if the latter, she cooked and washed, and tended the children. Of course, the women of the last century accepted, patiently enough, the rôle thrust upon them by circumstances. They were submissive to their lords, were thankful for their kindnesses, and forgave them their many sins. And it was not till early in the present century that the blue stocking appeared, to become a subject of ridicule. This was unfortunate, because the blue stockings, in a desultory, hesitating way, only tried to recover a portion of woman's lost ground. For a long time women who studied were looked upon with disfavour and suspicion. Why could not they make samplers and puddings, and play on the harpsichord? Some of them—poor things!—were obliged to learn in order to become governesses. But, really, what more ridiculous than that a woman should learn the same things as a man? Above all, why seek to change things?

Social prejudices are almost as hard to eradicate as those of religion. It was not till quite lately that the feeling against woman's rights as regards education was successfully combated; and even now there are hundreds of respectable parents who would far rather send their daughters to a fashionable boarding-school at Brighton, where they are sure to learn nothing, than to a place like the Hitchin College, where they will be taught with the same accuracy and thoroughness as Cambridge honour men.

We go up and down like a see-saw. After two hundred years our women are going to become students again; and after three hundred years they are going to become physicians again. Foremost among lady doctors is Mrs. Anderson. In the profession which she has taken up, particularly in those branches to which she is understood to have chiefly devoted her attention—the diseases of women and children—we wish her all the success that her courage and ability deserve. More: we hope that she is the forerunner of many other ladies who will take up the art of healing. Women can become at once nurses and doctors; their gentleness—not greater than that of some men, in spite of what is said—is more uniform: they have more patience; they are ready to devote more time. Only the conditions of things are changed. It is no longer necessary to know the properties of simples; it is necessary also to study the anatomy and framework of the body, to gain experience in the symptoms of disease, to go through a great deal that is repulsive and hard. It is no light thing to become a physician. We do not think that there will ever be a large proportion of women who will have the courage to face the difficulties and brave the labour. Many may, however, learn enough to make themselves invaluable nurses.

So will be restored the mediæval condition. Women will occupy themselves in household work, in study and literature, in looking after and educating children, in social amusements, in dances, music, and love-making. Man—poor, dear, patient animal!—goes on always the same: working for those he loves, striving to keep the nest warm, and caring little enough for aught else.

As for the rest, things are in a transition state, and consequently uncomfortable and disagreeable. Women, finding that their sphere is enlarged, want, naturally enough, to get as much as they can. Nor have they yet learned how to limit their aims to their strength. If they are prepared to give up love and marriage, or to subordinate these—with, of course, the welfare of their children—to other things; if, farther, they are willing to give up those social amenities to which they are accustomed—the concession of small things by men, the deference and respectful bearing of gentlemen towards them—then, by all means, let women go upon platforms, and fight in the arena, side by side with their brothers. Life is a great battle, in which, from time immemorial, women have been spared. If they want to enter it, let them come. But the battle is for existence: they will be struck down ruthlessly; and they will enter it, however well prepared and armed, with whatever ability of brain, with a feeble and delicate frame.

Meantime, it is all windbags and nonsense. A few women have got up a cry—partly from a wish to get notoriety, partly from a perfectly intelligible, if unreasonable, revolt against their own position, partly against one or two real grievances. They are the shrieking sisterhood. Their voices alone are heard. Their ranks are not increasing; but they make such a confounded clatter, that we quiet men believe the numbers to be tenfold what they really are.

The way to meet them is to argue as little as possible; to take away as much as possible all power to do mischief (by interfering in subjects in which, rightly or wrongly, they can know little, they have done a good deal of mischief already); to help all women, in every station, to honest work; to secure for women proper pay for work; to concede all that we can. Let us acknowledge at once that women can do everything; we may then invite them to illustrate their position. For it remains with them to establish the theory that they can do everything. Meantime, let us remember, and whisper among ourselves, that they have not yet produced in the first rank, be it remembered—a single musician, painter, poet, metaphysician, scholar, mathematician, chemist, physicist, physician, mechanician, or historian. One great, very great, novelist is a woman—George Sand. Second-and third-rate people of course are common as blackberries.

The best thing that can happen to a woman is to attract the love of a man: the best thing for a man is to love a woman. All the female men in the world cannot alter the laws of nature.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Anderson, who did not shine when she left her own line and went to the School Board, has, we hope, a successful and honourable career before her in her most noble and womanly work.