History of Hudson County and of the Old Village of Bergen/The Old Village of Bergen

The Old Village of Bergen

A History of the First Settlement in New Jersey

]hen the first representatives of the Amsterdam Licensed Trading West India Company built four houses on Manhattan Island in 1610–1612, one could hardly consider the territory crowded. Those ancestors of New York and New Jersey, however, had more spacious ideas than are held by their apartment-dwelling descendants. The charter of the Dutch East India Company, which had granted the trading monopoly to its West India Company, designated New Netherland as comprising "the unoccupied region between Virginia and Canada"—a little tract that must forever inspire pained admiration in modern real estate dealers. It was bounded approximately on the south by the South River, as the Dutch called the stream that the English afterward re-christened the Delaware. And because the Delaware was South River, the river explored by Henry Hudson in 1609, which first was called Mauritius River in honor of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, came to be referred to as North River, which explains why we today call it Hudson River or North River, just as the words happen.

]hen the first representatives of the Amsterdam Licensed Trading West India Company built four houses on Manhattan Island in 1610–1612, one could hardly consider the territory crowded. Those ancestors of New York and New Jersey, however, had more spacious ideas than are held by their apartment-dwelling descendants. The charter of the Dutch East India Company, which had granted the trading monopoly to its West India Company, designated New Netherland as comprising "the unoccupied region between Virginia and Canada"—a little tract that must forever inspire pained admiration in modern real estate dealers. It was bounded approximately on the south by the South River, as the Dutch called the stream that the English afterward re-christened the Delaware. And because the Delaware was South River, the river explored by Henry Hudson in 1609, which first was called Mauritius River in honor of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, came to be referred to as North River, which explains why we today call it Hudson River or North River, just as the words happen.

The Coming of the White Men

genuine interest in rivers. He was one of the many dreamers who for two centuries had been butting against the coast line, hoping for that rainbow thing, a passage to the golden East Indies. But the steady-minded Dutch traders who followed him thought very well of it. They saw it as a perfect water highway to the fur country, giving them almost direct access to the fur-trading Indian tribes of Canada, whose offerings passed from hand to hand down to Albany, while all along the banks could be gathered the almost equally rich tribute from the fur lands of Adirondacks and Catskills.

Its beauty, too, was loved by the Dutch. Dutch commercial instinct, Dutch thrift, never made the Dutchmen dull to the good art of living. They loved the straight wild cliffs of the Palisades. They loved the squall-darkened broad reach that they named the Tappan Zee. They loved the sweet

From the Mural by Howard Pyle, Hudson County Court House

tranquility of the vastly stretching sea meadows at its mouth, where flowed the rivers Hackensack and Passaic, the deep sound of the Kill von Kull, and many pleasant little streams that have been filled in long ago and are covered now by streets and towns.

They looked out from their New Amsterdam, and despite all ample Manhattan Island north of them, the western shore invited prettily. Its river mouths and undulating sea-grass plains and shining sleepy coves reminded them of home. Men who had come so far were not men to sit down and sink root in one little spot. The performances of Captains Hendrick Christæn and Adrien Blok are recommended earnestly to the attention of those who imagine that the Dutchman is a large body that moves slowly. Adrien Blok sailed from Holland in 1614. He arrived at Manhattan Island in 1614. His ship was destroyed there by fire in 1614 and he built himself another in 1614. Their handful of men built those four houses, and for good measure a fort, Fort Amsterdam, on the land above what later was known as Castle Garden, and now is the site of the Aquarium. They sailed up the North River and established a trading post. Fort Orange, on an island below Albany. They sailed through Hell Gate, which even now is no place for timid navigators, though it is not one-tenth as dangerous as it was then. They explored the whole great Long Island Sound to Cape Cod. They looked thoroughly into that tract which afterward became the Rhode Island Plantations. They investigated the Connecticut River. And they started the opening up of New Jersey by establishing a trading post on the west side of the North River opposite lower Manhattan, following it some years later with a small redoubt.

They might have left records as romantic as the narrative of Captain John Smith, for they explored and traded everywhere, from Cape Cod to the Delaware. But they were not men of the pen. We are not sure even of their exact names. The few scattered records refer with generous freedom to Adrien Blok, Adrian Block, Hendrik Christæn, Hendrick Christianse and Hendrick Christansen. The best people in that time were more than liberal in spelling, and many of the most important official documents have a sprightly way of giving two or more quite different spellings to the same name.

All around the handful of Europeans were Indians. Seacoast Indians came in canoes through the marsh thoroughfares and from the high lands beyond the Raritan. Warrior Indians came down the river in war canoes from their forests,

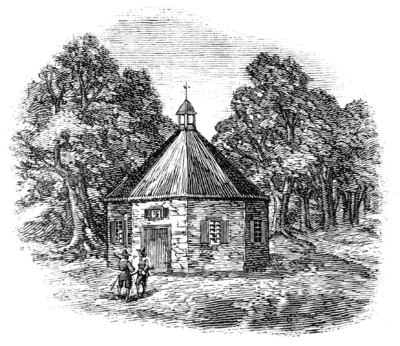

Prior's Mill, located near what is now the Corner of Fremont Street and Railroad Avenue

where they were well accustomed to contest the hunting rights with other tribes. For a long time there was little strife between them and the Dutch. The men of Holland were sharp traders, but they were not robbers or tyrants. From the very first they purchased instead of taking, and so, though Indian wars finally came into even their quiet history, they were wars not caused by attempt to snatch lands or other possessions from their savage neighbors.

They left the Indians to live their own free life, and the red men were well satisfied to exchange their furs, maize and

tobacco for the strange and tempting goods that had beenbrought across the great salt water. The Dutchmen smoked their long pipes in peace, cultivated tulips in the alien soil, drank their aromatic Hollands in taverns that were Holland

In the Old Dutch Days

transplanted, and walked forth in untroubled dignity with enormous guns to shoot the wild fowl whose wraithlike flights filled that sky which now is filled by wraiths of smoke from Sandy Hook to the Highlands of the Hudson.

During the next few years the silence of their bay was broken at rare intervals by a cannonshot below the narrows. Then all New Amsterdam gathered at the Battery and watched for wide sails over a wide ship—a ship almost as wide as long, but in all dimensions so small that we of today would think it no small adventure to make a mere coasting voyage on her. Out of the ship would come arrivals from Holland in wide breeches and noble Dutch hats, solid as the Dutch nation itself.

The passenger lists of these occasional ships could find room on small scraps of paper, yet the pioneers plainly felt that there was too much pressure of population, for only a few

From the Mural by Howard Pyle, Hudson County Court House

years after Adrien Blok built the first four dwellings some New Amsterdammers moved over the river. They selected a lovely wooded ridge that looked down on a green, water-cut foreland and temptingly across at the little Dutch houses of Manhattan.

Unfortunately these settlers did not leave a precise record, for they did not realize that they were making history by establishing the first settlement in New Jersey. Therefore we know only that "sometime between 1617 and 1620 settlements were made at Bergen, in the vicinity of the Esopus Indians and at Schenectady." We cannot even be sure that these first settlers in New Jersey were Dutch. "It is believed," says another historian, "that the first European settlement within the limits of New Jersey was made at Bergen about 1618 by a number of Danes and Norwegians who accompanied the Dutch to the New Netherland."

Various chronicles allege that the name "Bergen" was intended by these people of Scandinavian stock to perpetuate the name of the old city of Bergen in Norway. Others maintain that it was to recall Bergen op Zoom in Holland. But the word "bergen" also means "hills" or "mountains," and thus would have been an obvious title for the Dutch to give the ridge. Most of the names of early land-holders as recorded in the deeds of the succeeding epoch seem indubitably Dutch.

The Amsterdam Licensed Trading West India Company did not succeed in extending the colonization of the new

In 1629, the Company granted the famous charters to men who would undertake to found settlements, and who bore the title of Patroon. These charters conferred exclusive property in large tracts of land (sixteen miles along a river "and as far back as the situation of the occupiers would permit") with extensive manorial and seigneural rights. In return the Patroon bound himself to place at least fifty settlers on the land, provide each with a stocked farm, and furnish a pastor and a schoolmaster. The emigrants were bound to cultivate the land for at least ten years, bring all their grain to be ground at the Patroon's mill, and offer him first opportunity to purchase their crops.

Various directors of the West India Company, among them Goodyn, Bloemart, Van Renselaer and Pauuw, obtained charters as Patroons, and sent ships with agents to select land and make settlements. The land granted to Pauuw was Staten Island and a large tract along the North River shore opposite Manhattan Island. This holding along the river, "Aharsimus and Arresinck, extending along the River Mauritius and Island Manhatta on the east side and the island Hobocan-hackingh on the north" became the Patroonship of Pavonia. The name is said to have been based on the Latin equivalent for the Dutch word paaun, meaning peacock. Michael Pauuw, or Pauw as some records have it, was a burgher of Amsterdam and Baron of Achtienhoven in South Holland. Hobocan-hackingh, which was Indian for "the place of the tobacco pipe," later became known as Hoebuck, and is so referred to even in Revolutionary annals. Today it is Hoboken, and the tidal streams that made it an island hav ebeen long covered by streets.

After a few years, the Company sought to revoke Pauuw's Patroonship on the ground of non-fulfilment of contract; but they evidently found him a bird rather tougher than a mere peacock, for the records show that they had to buy him out, paying him 26,000 florins, or about $10,000. We find what look like echoes of that old dispute when we search through the meager history of the period; such laudatory remarks, for instance, as that "the Boueries and Plantations on the west side of the river were in prosperous condition," and such pessimistic reports as "in 1633 there were only two houses in Pavonia, one at Communipau, later occupied by Jan Evertsen Bout (who had come over as Pauuw's representative), and one at Ahasimus, occupied by Cornells Van Vorst, "who was successor to Bout.

In that same year of 1633, Michael Paulus erected a hut on a shore front of sand hills as a government trading post where the Indians could bring their product by canoe. The place became known as Paulus Hoeck. Some records give this

Van Wagenen's Cider Press. (Academy Street, west of Square)

trader's name as Paulaz, others call him Paulusen. For a time the Dutch name of the "Hoeck" was lost entirely, having been changed by ready spellers to "Powles's Hook." Then the original name came back, and that part of the shore was so known long after Jersey City was made into a municipality.

With the elimination of Patroon Pauuw, Paulus Hoeck was leased in 1638 to Abraham Isaacsen Verplanck. The sand hills covered about 65 acres, and they became popular for tobacco planting. In the past generations there has been so much filling in of shore front that the site of Paulus' trading post is more than a thousand feet inland.

Jan Evertsen Bout, the lone house-holder of Communipau, got a lease of Communipau from the Dutch West India Company in the same year, 1638. His yearly rental was set as "one quarter of his crops, two tuns of strong beer and 12 capons." Presumably the New Amsterdam representatives of the Company knew what to do with the two last items. In 1641, Hobocan-hackingh, or Hoebuck, was leased to Aert Teunisen Van Putten for twelve years, for a rental of "the fourth sheaf with which God Almighty shall favor the field." These, and a Bouerie in the Greenville section occupied by Dirck Straatmaker, were apparently the only notable settlements then existing in the large tract that afterward became the township of Bergen.

The conveyances of the lands that had belonged to the Patroonship of Pavonia were made by Director-General William Kieft. It is a melancholy duty to say that William Kieft lacked that equable disposition which so distinguished most of his fellow colonists. His zeal for the interests of the Dutch West India Company was perhaps sincere but certainly injudicious. When he went so far as to demand tribute of maize, furs and other supplies from the Indians, with threats of force if they refused, they responded in their own injudicious way by capturing or killing cattle. The peaceful intercourse of the past ceased, and mischief followed on mischief. Finally Kieft ordered an attack on an Indian encampment behind Communipaw, or rather Communipau, as it was called till well into the Nineteenth Century. The order was obeyed with unhappy punctuality. According to the records, "eighty soldiers on the night of February 27, 1643, under Sergeant Rodolph attacked the sleeping Indians and massacred all." From the Raritan to the Connecticut, red runners carried the news. There came an uprising of tribes so sudden and so terrible that almost over night the whole territory was swept clear of white men, "not a house was left standing and all Boueries were devastated."

The settlers who succeeded in escaping made their miserable way into New Amsterdam with the plaint: "Every place is abandoned. We wretched people must skulk with wives and little ones that are still left, in poverty together by and around the Fort at New Amsterdam."

What happened thereafter stands as a good memorial to the sober sense and the stout intelligence of these Dutchmen. In their misery, with the fruits of years of hard toil gone as in a whirlwind, they might have been excused for giving way to rage and hate. They might, as did many other pioneers in similar circumstances elsewhere, have cried for a war of extermination. They did not. These Holland men ran true to the Holland history of straight thinking. They complained to the States-General against the Director-General (or Governor, to use a common term for his office) and demanded his removal.

Holland was far away, Kieft did not lack friends, and governments move slowly. So it was 1646 before there was a decision; but when it came, it was the best that could have come, for the man who arrived in 1647 to govern the Colony was Petrus Stuyvesant—Petrus the hot-headed, Petrus the hot-hearted, Petrus who in his person exemplified in dramatic degree all that obstinacy side by side with tolerance, that courage mingled with liking for peaceful ways, that shrewdness grained with a deep honesty that has made the small Dutch nation a power in the world to be reckoned with, both in peace and war.

|

| Petrus Stuyvesant |

The great Petrus Stuyvesant—and he was indeed one of the greatest of the men who had come into the New World up to that time—was emphatically no pacificist. But he knew when to fight and when not to fight. Little by little he restored something of the old good relations, until settlers again dared to enter New Jersey. For ten years they planted and traded in peace. Then in 1654 the killing of an Indian girl on Manhattan Island caused another war. The Indians brought it home to New Amsterdam itself. On the New Jersey side they swept the country almost as before. "Not one white person remained in Pavonia." Twenty Boueries were destroyed and three hundred families were collected in the Fort on Manhattan Island.

Governor Stuyvesant had been away on a little war against the Swedes who had settled along the South River (Delaware) in defiance of Dutch claims. He returned quickly and again conciliated the Indians, even agreeing to pay ransom for their prisoners whom they held at Paulus Hook. Gradually peace returned, but there was not the old feeling of security. On January 18, 1656, the Director-General (or Governor as we shall call him hereafter) issued an Ordinance commanding all settlers to "concentrate themselves by the next spring in the form of towns, villages and hamlets so that they may be more effectually protected, maintained and defended against all assaults and attacks of the barbarians." To enable them to restore their holdings, another Ordinance exempted them from tithes and taxes for six years on condition that they obey the concentration order by establishing villages of at least twelve families.

The Dutch did not like to live in fear, and they did not like to live huddled. They were a sociable people but they wholly lacked the timid herd instinct. It was impossible for them to look over the rich valleys and bottom lands and remain content in close settlements. They had stout bodies and stout weapons—two arguments generally recognized as excellent for acquiring title to coveted domain. Yet despite the bitterness of two Indian wars, they still preferred more commonplace methods of real estate transaction. In January 30, 1658, Governor Stuyvesant and the Council of New Netherland acquired by purchase from the Indians a tract of land lying along the west side of the North River. This territory was signed over for the red men by the Indian chiefs Therincques, Wawapehack, Seghkor, Koghkenningh, Bomokan, Memiwockan, Sames and Wewenatokwee (which presumably was a casual approximation to their real names by the honest Dutch scribes and notaries) to "the noble Lord Director-General Pieter Stuyvesant and Councill of New

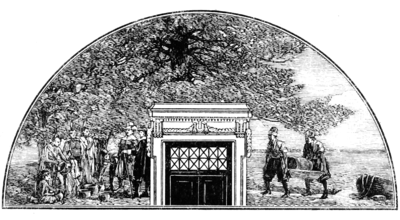

"There Came an Uprising of Tribes"

From the Lunette by C. Y. Turner, Hudson County Court House

Netherlandt." It is described as "beginning from the Great Klip above Wiehachan and from there right through the land above the island Sikakes and therefrom thence to the Kill von Coll, and so along to the Constable Hoeck, and from the Constable Hoeck again to the aforesaid Klip above Wiehachan."

The word "Klip" was Dutch for "cliff." It is hardly necessary to explain what places were meant by Wiehachan and Sikakes. Merely as a matter of superfluous accuracy we mention apologetically that they were Weehawken and Secaucus. Secaucus was scarcely an island. It was a strip of firm land surrounded by tidal marsh. For some reason it was highly prized by planters. Its name was Indian for "place of snakes" and it and Snake Hill or Rattlesnake Hill, appear frequently in subsequent land transfers.

Paying for the Land

From the Lunette by C. Y. Turner, Hudson County Court House

For the territory thus sold, which included all the land between the North and Hackensack Rivers and the Kill von Kull, the Indians received "80 fathoms of wampum, 20 fathoms of cloth, 12 brass kettles, 1 double brass kettle, 6 guns, 2 blankets, and one-half barrel of strong beer." It does not seem much; but wampum was good Indian money, and 80 fathoms is 480 feet, and 480 feet of good money would seem not insignificant even today. One wonders, however, how the tribes divided the one "double brass kettle" and who drank the beer. In 1920, this territory was assessed for taxes on a valuation of $671,141,067. It seems to have been one of those excellent transactions that permanently satisfied both parties to the bargain.

Despite the purchase, the concentration orders and the remission of taxes remained in force, and on August 16, 1660, a petition for farming rights was granted to several families on condition that, first, a spot must be selected which could be defended easily; second, each settler to whom land was given free must begin to build his house within six weeks after drawing his lot; third, there must be at least one soldier enlisted from each house, able to bear arms to defend the village.

In November of the same year the village of Bergen was founded "by permission of Peter Stuyvesant, Director-General, and the Council of New Netherland," and thus Bergen, (described as being "in the new maize land") besides being the earliest settlement in New Jersey also holds the honor of being the first permanent settlement in New Jersey.

The site of the original village is marked by the present Bergen Square and the four blocks surrounding it, the boundaries being Newkirk and Vroom Streets north and south, Tuers Avenue east and Van Reypen Street west. There were two cross roads, and they are still represented today by existing streets. The present Bergen Avenue was the road to the Kill von Kull and also to Bergen Woods, now known as North Hudson. Academy Street of today was then the Communipaw road. From their height the inhabitants looked over island-dotted and stream-divided meadows of tall sea-grass, swarming with wild fowl and rich with fish. Those bright, unstained expanses gave them mighty crops of salt hay for no trouble save that of harvesting it. They were crops that could not fail so long as the tides ran. Everywhere the salt tides were the Dutchman's friend. He utilized high flood to bring craft close to his farms for easy loading or unloading. He used the ebb to help him to the bay and so to market at New Amsterdam. He used the flood to help him home again. Indeed, his very land-roads were tidal; for the lower reaches to Paulus Hook and other shores were often under sea in the full-moon tides.

In the center of the village, which was in the form of a square 800 feet long on each side, its founders established a vacant space, recorded as being 160 by 225 feet. In great part this remains as today's Bergen Square. Around the whole village was a palisade of strong logs, with openings at the two cross roads. Daniel Van Winkle, Bergen's accomplished historian, says that Tuers Avenue and Idaho Avenues on the east and west, and Newkirk and Vroom Streets on the north and south, mark the line of these palisades. In the evening, or when there were rumors of Indian trouble, the cattle were driven in and the openings barred by heavy gates. The farms expanded throughout the surrounding country, and were called "Buytentuyn."

On September 5th, 1661 , the Director-General and Council, in response to a petition by the inhabitants, granted the town "an Inferior Court of justice with the privilege of appeal to the Director-General and Council of New Netherland, to be by their Honors finally disposed of, this Court to consist of one Schout who shall convene the appointed Schepens and preside at the meetings." By this Ordinance, Bergen became the first civic government to be established in the Colony. The first Schout was Tielman Van Vleck. The Schepens were Michael Jansen (Vreeland), Harman Smeeman and Caspar Stynmets.

The creation of this Court gave Bergen the dignity of seat of government for all the surrounding country, for the grant of 1660 had conveyed to the inhabitants "the lands with the meadows thereto annexed situated on the west side of the North River in Pavonia, in the same manner as the same was by us purchased of the Indians." Thus the freeholders of Bergen held all of what is now known as Hudson County.

The Schout and the Schepens soon had their hands full. The placid Dutchman had a placid way of insisting stubbornly

Second Church, Erected 1733

Bergen Avenue and

Vroom Street

Most numerous of all were the disputes over land boundaries. The government grants were beautifully vague, and some of the cases must have made the official heads ache, as for instance, in the case of title such as Claus Pietersen's, which called for "138 acres bounded west by the Bergen Road and north by Nicholas the baker," or the town lot deeded to Adrien Post as being "on the corner by the northwest gate in Bergen, and a garden on the northwest side of the town."

There were other famous cases that shook the community. Their records have, unhappily, been lost, but their tenor is illustrated by the appeals that came before the Council in after years. One was the great hog case which Captain John Berry carried indignantly to the Council on appeal against the Schout, complaining that the Schout and Schepens had "instituted actions against him for carrying off some hogs as if he had obtained them in a scandalous manner, by stealing" whereas he had simply taken his own hogs from an enclosure where they were being withheld from his possession. The Schout informed the Council that the Captain had not been charged with stealing but simply with "inconsiderate removal of the hogs." The Captain, thus pressed, acknowledged that perhaps he had "rashly removed the said hogs." The Director-General and Council, after deep deliberation, solemnly cleared Captain Berry of the suspicion of theft, but found that he "had gone too far in inconsiderate removal of the hogs"—and fined him one hundred guilders.

The surrounding little settlements also did not always agree with the Schout and Schepens. The latter had to complain in 1674 to the General Council that the inhabitants of "the dependent hamlets of Gemoenepa, Mingaghue and Pemrepogh" had refused to carry out an agreement "respecting the making and maintaining of a certain common fence to separate the heifers from the milk cows, and that they also refused to pay their quota for support of the Precentor and the Schoolmaster."

The men of the three hamlets were so indignant that they almost issued a Declaration of Independence. There were great ferriages to the Fort at Manhattan to fight it out. The Council debated and decreed. So fierce became the contest that arbitrators were appointed and greater debates ensued. The arbitrators met the fate of all arbitrators. Gemoenepa, Mingaghue and Pemrepogh did not like their decision, and therefore unanimously called it no decision at all. Loureno Andriese, Samuel Edsall and Dirk Claesen went to the Fort on behalf of the hamlets and demanded that the Schout and Schepens be ordered once and for all to "leave the petitioners undisturbed about the fence." In the end the Council evidently got impatient, for it issued a decree ordering the hamlets to attend to both the fence and the quota, and to do it at once. The records do not show if they did. Knowing the fine, upstanding firmness of the race, it may be that the cows and the Precentor and the Schoolmaster passed away from old age with the matter still unsettled.

Petrus Stuyvesant soon had more serious things to consider than appeals from decisions of Schout and Schepens. In 1664, Charles II of England in his large, generous way granted his brother, the Duke of York, a royal charter for the "whole region from the west bank of the Connecticut River to the east shore of the Delaware." The Duke, without pausing for the trivial details of proving title, promptly conveyed to Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret all the territory that now is New Jersey. The early voyages of the Cabots were the foundation of the English claim. The small fact that these voyages were made in 1498 was not permitted to disturb the legal mind.

Colonel Richard Nichols with three ships of 130 guns and with 600 men appeared before New Amsterdam. Everybody knows how brave old Petrus wanted to blow up the fort and all within it rather than to surrender, and how the burgers declined to go to a glorious death.

The English took the place and immediately renamed it New York. It seems to have been the most important change

The Coming of the English

that they made. The inhabitants remained Dutch in everything save the flag that flew over them, and they accepted that emblem philosophically, holding fast to their ways, their trade and their lands, and letting emblems be emblems. The new rulers were more concerned with keeping the Colony than with changing it. They confirmed all the old grants, or most of them.

At first the New Jersey territory was called Nova Cesarea, but the name New Jersey soon became the common one. In a charter granted on September 22, 1668, by Sir Philip Carteret, brother of Sir George and Governor of the new province, he confirmed the original grants to "the Towne and the Freeholders of Bergen and to the Villages and Plantations thereunto belonging." The township was estimated in this deed as comprising 11,520 acres, which was probably a mere

From the Mural by Hoivard Pyle, Hudson County Court House

guess since it seems to have been too little by half. It was about sixteen miles long and four miles wide "including the said Towne of Bergen, Communipaw, Ahassimus, Minkacque, and Pembrepock, bounded on the east, south and west byNew York and Newark Bays and the Hackensack River." By the conditions of the charter the freeholders were bound to pay "to the Lords Proprietors and their successors on every twenty-fifth day of March fifteen pounds as quit rent forever." The boundaries fixed in this charter remained unchanged till the Act of Legislature that in 1843 constituted a new County of Hudson.

Among other confirmations of previous grants we find a record of a deed "to Laurence Andriessen of the land in the tract called Minkacque under the jurisdiction of Bergen, northeast of Lubert Gilbertsen, southwest of Derrick Straetmaker, comprising fifty Dutch Morgen (a Dutch land measurement) for a quit rent of one penny English for each acre," and a confirmation of patent to "Isaacsen Planck for a neck of land called Paulus Hook or Aressechhonk, west of Ahasimus."

On July 30, 1673, during the second war between England and Holland, a Dutch fleet took New York, and re-christened it New Orange. Aside from changing the name and calling on all the inhabitants to swear allegiance, which they did with cheerful good will, things remained as they had been; and when the peace of 1674 definitely turned over New Netherland to England, the colonists changed flags again unruffled and—remained Dutch. The record of the Oath of Allegiance to the Dutch government enumerates "78 inhabitants of Bergen and dependencies, of whom 69 appeared at drum beat." A report of 1680 describes Bergen as "a compact town" containing about 40 families.

Gradually, to be sure, English people came in. New York was growing into a great town, and it drew merchants and adventurers from all parts, becoming indeed so metropolitan that even the pirates of the seven seas esteemed it as an excellent market for their plunder. But on the western bank of the river the old habits of Holland remained so fixed that we still find characteristic Dutch traits, Dutch architecture, even Dutch customs from the Hudson to the Ramapos.

In 1682, the Province of New Jersey was divided into four Counties—Bergen, Essex, Middlesex and Monmouth; and in 1693 each County was divided into townships. In 1714, an Act gave a new charter to "The Inhabitants of the Town of Bergen."

With the growth of population Paulus Hook became an important place. The Van Vorst family had acquired it in 1669, and it remained in their possession till well into the Nineteenth Century. It was the natural terminus for ferries to New York and stage lines had been established early. By 1764, Paulus Hook was more than a mere ferry landing. It was the terminus of the stage routes from Philadelphia. In the New York Mercury of that year we find the announcement that "Sovereign Sybrandt informs the Public he has fitted up and completed in the neatest Manner a new and genteel stage Waggon which is to perform two Stages in every week from Philadelphia to New York, from Philadelphia to Trenton, from Trenton to Brunswick and from Brunswick to the said Sybrandt's House and from said Sybrandt's House by the new and lately established Post Road (on Bergen which is now generally resorted to by the Populace, who prefer a Passage by said Place, before the Danger of crossing the Bay) to Powles's Hook opposite to New York where it discharges the Passengers. Each single person only paying at the Rate of Two Pence Half-Penny per mile from said Powles's Hook to said Sybrandt's House and at the rate of Two Pence per Mile after.—N. B. As said Sybrandt now dwells in the House known by the Sign of the Roebuck which House he has now finished in a genteel Manner and has laid in a choice Assortment of Wines and other Liquors, where Gentlemen Passengers and others may at all Times be assured of meeting with the best of Entertainment."

Michael Cornelison also operated a stage line to and from Philadelphia and a ferry to New York. He had a tavern on

First Voyage of the Clermont, 1807

From the Lunette by C. Y. Turner, Hudson County Court House

Paulus Hook, and he was firm with passengers. They had to arrive from New York the day before. Between sunset and sunrise Cornelison considered the river officially closed.

Paulus Hook also had a race track. It was established in 1769 by Cornelius Van Vorst and it was pounded democratically by the hoofs of blooded horses belonging to New York sports and by the larger hoofs of the corpulent steeds belonging to the countryside. There was a noble race in 1771, "round the course at Powles Hook, a match for Thirty Dollars between Booby, Mug and Quicksilver, to run twice around to a heat, to carry catch riders." In the Bergen woods, the gentry had regular fox hunts on horseback in English style.

No greater things excited these peaceful people till the time of the Revolution. Then, though that country was spared any great battles, it had its share of marches and counter-marches, skirmishes and alarms. It was a raiding ground, for

Washington and His Officers

From the Lunette by C. Y. Turner, Hudson County Court House

it was rich in fat cattle and plentiful farm produce, and as always in war, the non-belligerent population suffered all the hardships without any of the glory. It appears humorous now to read the wail of certain burghers who were stopped by a raiding party on their way home from church and stripped of their breeches; but undoubtedly it seemed a bitter thing to the owners. There were more serious things, too, and in plenty. There were sudden raids at night, with burnings and killings, or at the least with plundering that left homesteads stripped bare of cattle and goods.

After Long Island was evacuated by Washington's troops and it was decided impossible to hold New York, much of the artillery and stores and many wounded were taken to the New Jersey shore for transportation to Newark. An account dated "Paulus Hook, September 15, 1776," says: "Last night the sick were ordered to Newark in the Jersies, but most of them could be got no further than this place and Hoebuck, and as there is but one house at each of these places, many were obliged to lie in the open, whose distress when I walked out at daybreak gave me a livelier idea of the horror of war than anything I ever met with before. About 8 a. m, 3 large ships came to sail and made towards the Hook. They raked the place with grape and killed one horse. On the night of the 17th, the garrison tried to burn the ships which had anchored 3 miles above. They grappled the Renown of 50 guns but failed. She cannonaded us again later. Colonel Duyckinck this morning retired to Bergen leaving Colonel Durkee on the Hook with 300 men." After three days' cannonading by ships, the Americans withdrew and thereafter the British held Paulus Hook. Bergen remained the headquarters of the American forces till it too was evacuated.

The British were not permitted to hold even the Hook undisturbed. American parties made daring raids again and again, the most famous of these being known as the Battle of Paulus Hook. On the night of August 19, 1779, Major Lee (the celebrated Light Horse Harry of Revolutionary annals) brought his men across the Hackensack and through enemy territory along a perilous causeway through the swamps, falling on the British so suddenly and fiercely that he was able to carry back with him 7 officers and 100 privates.

The loyalist New York Gazette of August 28, 1780, said: "General Washington, the Marquis de la Fayette, Generals Greene and Wayne with many other Officers and a large body of Rebels have been in the vicinity of Bergen for some days past. They have taken all the forage from the Inhabitants of

Columbia Academy, Northeast Corner, Bergen Square

that Place and left them destitute of almost everything for their present and Winter Subsistence."

The editors of the New York papers may be excused. They existed by grace of the British military authorities, and the military authorities had a hard time explaining why all their troops and warships and other plentiful means could neither force a passage of the Hudson past West Point nor break that "pitiful line of ragged Rebels" that held the long line all the way from the Ramapos to the upper Hudson. So they indulged themselves in the thin comfort of printing sarcastic things about them. The Royal Gazette, published by the notorious Rivington, "printer to His Majesty in New York," was particularly martial about it, and it was this journal that delighted its readers with a succession of verses called "The Cow Chace" in which the Revolutionary Generals were agreeably pictured asrustics, drunkards and dunces.

"The Cow Chace" based on a raid by General Anthony Wayne on a British block house at Bull's Ferry near Hoboken, was the work of a young British officer named Major Andre. If he was a little crude in literary etiquette and a very poor poet indeed, he knew how to die as a brave and honest gentleman. He is said to have given the last canto of his epic to the editor of the Royal Gazette on the day before he left New York for his disastrous conference with Benedict Arnold at West Point. The final verses appeared in the edition that was published on the very morning when the gay, gallant young fellow was captured:

"Yet Bergen cows still ruminate

Unconscious in the stall

What mighty means were used to get

And lose them after all.

*****

And now I've clos'd my epic strain

I tremble as I show it,

Lest this same warrior-drover, Wayne,

Should ever catch the poet."