Lake Ngami/Chapter 16

CHAPTER XVI.

We had been nearly three days at Nangoro's capital before its royal occupant honored our camp with his presence. This unaccountable delay gave us some uneasiness; yet we could not but surmise that he had been longing to see us during the whole time. I believe it, however, to be a kind of rule with most native princes of note in this part of Africa, to keep strangers waiting in order to impress them with a due sense of dignity and importance.

If obesity is to be considered as a sign of royalty, Nangoro was "every inch a king." To our notions, however, he was the most ungainly and unwieldy figure we had ever seen. His walk resembled rather the waddling of a duck than the firm and easy gait which we are wont to associate with royalty. Moreover, he was in a state of almost absolute nudity, which showed him off to the greatest possible advantage. It

INTERVIEW WITH KING NANGORO.

appeared strange to us that he should be the only really fat person in the whole of Ondonga. This peculiarity no doubt is attributable to the custom that prevails in other parts of Africa, viz., that of selecting for rulers such persons only who have a natural tendency to corpulence, or, more commonly, fattening them for the dignity as we fatten pigs.[1]

With the exception of a cow and an ox, Nangoro appeared to appreciate few or none of the presents which Mr. Galton bestowed on him. And as for my friend's brilliant and energetic orations, they had no more effect on the ear of royalty than if addressed to a stock or a stone. It was in vain that he represented to his majesty the advantages of a more immediate communication with Europeans. Nangoro spoke little or nothing. He could not be eloquent because excessive fat had made him short-winded. Like Falstaff, his "voice was broken." Any attempt on his part to utter a sentence of decent length would have put an end to him, so he merely "grunted" whenever he desired to express either approbation or dissatisfaction.

In common with his men, he was at first very incredulous as to the effect produced by fire-arms; but when he witnessed the depth that our steel-pointed conical balls penetrated into the trunk of a sound tree, he soon changed his opinion, and evidently became favorably impressed with their efficacy. As for the men of his tribe who had not yet seen guns, and who had flocked to the camp to have a look at us, they became so alarmed that, at the instant of each discharge, they fell flat on their faces, and remained in their prostrate position for some little time afterward. A few very indifferent fireworks which we displayed created nearly equal surprise and consternation.

In another interview with Nangoro he requested us to shoot some elephants, which were said to abound at no great distance, and which, at times, committed great havoc among the corn-fields, trampling down what they did not consume. However much we might have relished the proposal under other circumstances, we now peremptorily refused to comply. We reasoned thus: "Supposing we were successful, Nangoro would not only bag all the ivory—an article he was known to covet and to sell largely to the Portuguese—but he would keep us in Ondonga till all the elephants were shot or scared away." Neither of these results suited our purpose. The cunning fellow soon had an opportunity of revenging himself on us for this disregard of his royal wish.

On paying our respects to his majesty one day, we were regaled with a prodigious quantity of beer, brewed from grain, and served out of a monster calabash with spoons (made from

BEER-CUP AND BEER-SPOON.

diminutive pumpkins), in nicely-worked wooden goblets. Being unwell at the time, I was not in a state properly to appreciate the tempting beverage. Nangoro, however, who probably attributed the wry face that I made to the influence of the liquor, suddenly thrust his sceptre, which, by the way, was simply a pointed stick, with great force into the pit of my stomach. I was sitting cross-legged on the ground at the time, but the blow was so violent as to cause me to spring to my feet in an instant. Nangoro was evidently much pleased with his practical joke. As for myself, I sincerely wished him at the antipodes. However, for fear of offending royalty, I choked my rising anger, and reseated myself with the best grace I could, but I tried in vain to produce a smile.

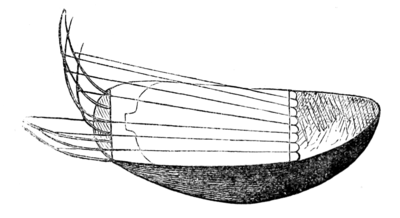

On another occasion we attended a ball at the royal residence. An entertainment of this kind was given every night soon after dark, but it was the most stupid and uninteresting affair I ever witnessed. The musical instruments were the well-known African tom-tom and a kind of guitar.

GUITAR.

The features of the Ovambo women, though coarse, are not unpleasing. When young they possess very good figures. As they grow older, however, the symmetry gradually disappears, and they become exceedingly stout and ungainly. One of the causes of this is probably to be found in the heavy copper ornaments with which they load their wrists and ankles. Some of the ankle-rings must weigh as much as two or three pounds, and they have often a pair on each leg. Moreover, their necks, waists, and hips are almost hidden from view by a profusion of shells, cowries, and beads of every size and color, which sometimes are rather prettily arranged.[2] Another cause of their losing their good looks in comparatively early life is the constant and severe labor they are obliged to undergo. In this land of industry no one is allowed to be idle, and this is more especially the case with the females. Work begins at sunrise and ends at sunset.

The hair of both men and women is short, crisp, and woolly. With the exception of the crown, which is always left untouched, the men often shave the head, which has the effect of magnifying the natural prominence of the hinder parts of it. The women, on the other hand, not satisfied with the gifts nature has bestowed upon them, resort, like the polished ladies of Europe, to artificial exaggerations. They besmear and stiffen the hair with cakes of grease and a vermilion-colored substance, which, from being constantly added to and pressed upon it, gives to the upper part of the

OVAMBO.

head a broad and flat look. The persons of the women are also profusely besmeared with grease and red ochre.

Besides ear-rings of beads or shells, the men display but few ornaments. With regard to clothing, both sexes are far more scantily attired than the Damaras. When grown up, they chip the middle tooth in the under jaw.

The Ovambo, so far as came under my own observation, were strictly honest. Indeed, they appeared to entertain great horror of theft, and said that a man detected in pilfering would be brought to the king's residence and there speared to death. In various parts of the country a kind of magistrate is appointed, whose duty is to report all misdemeanors. Without permission, the natives would not even touch any thing, and we could leave our camp free from the least apprehension of being plundered. As a proof of their honesty, I may mention that, when we left the Ovambo country, the servants forgot some trifles, and such was the integrity of the people that messengers actually came after us a very considerable distance to restore the articles left behind. In Damara and Namaqua-land, on the contrary, a traveler is in constant danger of being robbed, and, when stopping at a place, it is always necessary to keep the strictest watch on the movements of the inhabitants.

But honesty was not the only good quality of this fine race of men. There was no pauperism in the country. Crippled and aged people, moreover, seemed to be carefully tended and nursed. What a contrast to their neighbors, the Damaras, who, when a man becomes old, and no longer able to shift for himself, carry him into the desert or the forest, where he soon falls a prey to wild beasts, or is left to perish on his own hearth! Nay, he is often knocked on the head, or otherwise put to death.

The Ovambo are very national, and exceedingly proud of their native soil. They are offended when questioned as to the number of chiefs by whom they are ruled. "We acknowledge only one king. But a Damara," they would add, with a contemptuous smile, "when possessed of a few cows, considers himself at once a chieftain."

The people have also very strong local attachments. At an after period, while Mr. Galton was waiting at St. Helena for a ship to convey him to England, he was told "that slaves were not exported from south of Benguela because they never thrived when taken away, but became home-sick and died." This, no doubt, refers in part to the Ovambo. Moreover, though people of every class and tribe are permitted to intermarry with them, they are, in such case, never allowed to leave the country.

The Ovambo are decidedly hospitable. We often had the good fortune to partake of their liberality. Their staple food is a kind of coarse stir-about, which is always served hot, either with melted butter or sour milk.

Being once on a shooting excursion, our guide took us to a friend's house, where we were regaled with the above fare. But, as no spoons accompanied it, we felt at a loss how to set to work. On seeing the dilemma we were in, our host quickly plunged his greasy fingers into the middle of the steaming mess, and brought out a handfull, which he dashed into the milk. Having stirred it quickly round with all his might, he next opened his spacious mouth, in which the agreeable mixture vanished as if by magic. He finally licked his fingers and smacked his lips with evident satisfaction, looking at us

MEAT-DISH.

as much as to say, "That's the trick, my boys!" However unpleasant this initiation might have appeared to us, it would have been ungrateful, if not offensive, to refuse; therefore we commenced in earnest, according to example, emptying the dish, and occasionally burning our fingers, to the great amusement of our swarthy friends.

Although generally very rich in cattle, and fond of animal diet, their beasts would seem to be kept rather for show than for food. When an ox is killed, the greater portion of the animal is disposed of by the owner to the neighbors, who give the produce of their ground in exchange.

The morality of the Ovambo is very low, and polygamy is practiced to a great extent. A man may have as many wives as he can afford to keep; but, as with the Damaras, there is always one who is the favorite and the highest in rank. Woman is looked upon as a mere commodity—an article of commerce. If the husband be poor, the price of a wife is two oxen and one cow; but should his circumstances be tolerably flourishing, three oxen and two cows will be expected. The chief, however, is an exception to this rule. In his case, the honor of an alliance with him is supposed to be a sufficient compensation. Our fat friend Nangoro had largely benefited by this privilege; for, though certainly far behind the King of Dahomey in regard to the number of wives, yet his harem boasted of one hundred and six enchanting beauties!

In case of the death of the king, the son of his favorite wife succeeds him; but if he has no male issue by this woman, her daughter then assumes the sovereignty. The Princess Chipanga was the intended successor to Nangoro. My friend thought that his bearded face had made an impression on this amiable lady; but, though experience has since taught us that he was by no means averse to matrimony, he preferred to settle his affections on one of his own fair country-women rather than marry the "greasy negress" Chipanga, heiress of Ondonga.

We read of nations who are supposed to be destitute of any religious principles whatever. If we had placed reliance on what the natives themselves told us, we should have set down the Ovambo as one of such benighted races. But can there be so deplorable a condition of the human mind? Does not all nature forbid it? Do not the sun, the moon, the stars, the solemn night, and cheerful dawn, announce a Creator even to the children of the wilderness? Is it not proclaimed in the awful voice of thunder, and written on the sky by

- "the most terrible and nimble stroke

- "the most terrible and nimble stroke

Of quick, cross lightning?"

Is it possible that any reasoning creature can be so degraded as not to have some notion, however faint and inadequate, of an Almighty Being? Such a conception is necessarily included, more or less, in all forms of idolatry, even the most absurd and bestial. The indefinable apprehensions of a savage, and his dread of something which he can not describe, are testimonies that at least he suspects (however dimly and ignorantly) that the visible is not the whole. This may be the germ of religion—the first uncouth approaches of "faith" as the "evidence of things not seen"—the distant and imperfectly-heard announcement of a God.

May not our incorrect ideas on this head, in reference to the Ovambo, be attributed to want of time and insufficient knowledge of their language, habits, and shyness in revealing such matters to strangers? When interrogating our guide on the subject of religion, he would abruptly stop us with a "Hush!" Does not this ejaculation express awe and reverence, and a deep sense of his own utter insufficiency to enter on so solemn a theme? The Ovambo always evinced much uneasiness whenever, in alluding to the state of man after death, we mentioned Nangoro. "If you speak in that manner," they said in a whisper, "and it should come to the hearing of the king, he will think that you may want to kill him." They, moreover, hinted that similar questions might materially hurt our interest, which was too direct a hint to be misunderstood. To speak of the death of a king or chief, or merely to allude to the heir-apparent, many savage nations consider equivalent to high treason.

As already said, the Ovambo surround their dwellings

DWELLING-HOUSE AND CORN-STORES.

with high palisades, consisting of stout poles about eight or nine feet in height, fixed firmly in the ground at short intervals from each other. The interior arrangements of these inclosures were most intricate. They comprised the dwelling-houses of masters and attendants, open spaces devoted to amusement and consultation, granaries, pig-sties, roosting-places for fowls, the cattle kraal, and so forth.

Their houses are of a circular form. The lower part consists of slender poles, about two feet six inches high, driven into the ground, and farther secured by means of cord, &c., the whole being plastered over with clay. The roof, which is formed of rushes, is not unlike that of a bee-hive. The height of the whole house, from the ground to the top of the "hive," does not much exceed four feet, while in circumference it is about sixteen.

They store the grain in gigantic baskets, generally manufactured from palm-leaves, plastered with clay, and covered with nearly the same material and in the same manner as the dwelling-houses. They are, moreover, of every dimension, and by means of a frame-work of wood are raised about a foot from the ground.

The domestic animals of the Ovambo are the ox, the sheep, the goat, the pig, the dog, and the barn-door fowl. The latter was of a small breed, a kind of bantam, very handsome, and, if properly fed and housed, the hens would lay eggs daily.

The wet season in these latitudes commences about the same period as in Damara-land, that is, in October and November. When the first heavy rains are over, the Ovambo begin to sow grain, &c.; but they plant tobacco in the dry

VIEW IN ONDONGA.[3]

The chief article of export is ivory, which they procure from elephants caught in pitfalls. In exchange for this they obtain beads, iron, copper, shells, cowries, &c.; and such articles as they do not consume themselves they sell to the Damaras. As far as we could learn, they make four expeditions annually into Damara-land, two by the way of Okamabuti, and two by that of Omaruru. The return for these several journeys, on an average, would seem to be about eight hundred head of cattle. Since we were in the country, however, it is probable that great changes may have taken place.

Next to their cattle they prize beads; but, though they never refuse whatever is offered to them, there are some sorts that they more especially value, and it is of very great importance to the traveler and the trader to be aware of this, as, in reality, beads constitute his only money or means of exchange. Thus, throughout Ondonga, large red (oval or cylindrically-shaped), large bluish white, small dark indigo, small black (spotted with red), and red, in general, are more particularly in request.

The Ovambo have some slight knowledge of metallurgy. Though no mineral is indigenous to their own country, they procure copper and iron ore in abundance from their neighbors, which they smelt in fire-proof crucibles. The bellows employed in heating the iron are very indifferent, and stones serve as substitutes for hammer and anvil. Yet, rude as these implements are, they manage not only to manufacture their own ornaments and farming tools, but almost all the iron-ware used in barter.

BLACKSMITHS AT WORK.

- ↑ In speaking of the Matabili, Captain Harris says, "To be fat is the greatest of all crimes, no person being allowed that privilege but the king." Here, then, we have a new kind of lèse-majesté. According to some of the African tribes, obesity in plebeians is high-treason!

- ↑ These ornaments, together with a narrow and soft piece of skin in front, and another behind of stout hide, constitute the dress of the Ovambo ladies.

- ↑ The above wood-cut is a view of the country near Nangoro's residence. The huts in the distance are those of Bushmen. A great number of these people dwell among the Ovambo, to whom they stand in a kind of vassalage and relationship.