Mexico, as it was and as it is/Letter 18

LETTER XVIII.

priests. temples. sacrifices.

The Priests have always borne an important part in Mexican affairs, and it is stated, upon good authority, that at the height of the power of the Empire, they numbered not less than one million in the service of the different idols.

They were divided into different orders, and there were both monks and priests, as among the Catholics. Women, also, entered into the sacred order, and performed all the duties usually assigned to the males, except that of sacrifice. The monks were called Hamacazques, and the priests Teopixqui.

They had two chiefs, who obtained their rank and power by lives of exemplary probity and virtue, and by a profound acquaintance with all the rites and mysteries of their religion. These were the "diviners" or soothsayers, who were consulted by the authorities on all high matters of state, both in peace and war. They officiated at the most solemn of their sacrifices, and crowned the sovereign upon his accession to the throne. On the principal festivals their dress was splendid, and bore the insignia of the god in whose honor they officiated. To the minor priesthood, all the humble duties of the temples were assigned; they cleaned the sacred edifice, educated the young, took care of the holy pictures, and observed the Calendar.

Nor did they lack a resemblance to portions of the Catholic clergy, in the austerity and mortification of their lives. Not only did they wear sackcloth next their skin and apply the scourge in secret, but they shed their own blood; pierced themselves with the sharp points of the aloe; and bored their ears, lips, tongues, arms and legs, by introducing fragments of cane, which they gradually increased in size, as their wounds began to heal. Their fasts, too, were long and severe.

Each sex lived apart, leading a life of celibacy, in monastic establishments, and their income was derived from lands set aside for their maintenance,—separate revenues being devoted to the support of the Temple.

It is in their sacred edifices that these people were the most remarkable, and, as in Egypt, they are probably the only remains that will be discovered in our day and generation.

I shall have occasion, hereafter, to give some descriptions of other Teocallis, "Houses of God"—and Teopans, "Places of God;" but I cannot refrain, in this connection, from giving you some idea of the condition of the great Temple of Mexico at the period of the conquest, as the account of it comes from eye-witnesses, between whom there can by no possibility have been a collusion to impose either upon the sovereign for whom the one wrote, or, upon the mass of the Spanish nation to which the writings of the others were addressed.

It is related that in the year 1486, Ahuitzotl, the eighth King of Mexico and predecessor of Montezuma, completed the great Teocalli in his capital.

[1]This magnificent edifice occupied the centre of the city, and, together with the other temples and buildings annexed to it, comprehended all that space upon which the great Cathedral church now stands, part of the greater market place, and part of the neighboring streets and buildings.

It was surrounded by a wall eight feet thick, built of stone and lime crowned with battlements in the form of niches, and ornamented with many stone figures in the shape of serpents. Within this inclosure, it is affirmed by Cortéz, that a town of five hundred houses might have been built!

It had four gates fronting the cardinal points, and over each portal was a military arsenal filled with needful equipments.

The space within the walls was beautifully paved with polished stones, so smooth that the horses of the Spaniards "could not move over them without slipping," and in the centre of this splendid area arose the great Teocalli. This was an immense truncated pyramid of earth and stones, composed of four stories or bodies; an idea of which may perhaps be obtained by an inspection of the following drawing, taken from one made by the Anonymous Conqueror, which may be found in the collection of Ramusis, and in the Œdipus Ægyptiacus of Father Kircher.

The top of this pyramid (as appears from the design) was not reached by a flight of steps from the base on the front of the edifice but by a stairway passing from body to body; so that a person, in ascending, was obliged to move four times around the whole of the Teocalli before he reached its summit. The width of these spaces or stones, at the base of each body, was five or six feet, and it is alleged that three or four persons abreast could easily pass round them.

There is some difference of opinion among the old writers, as to the dimensions of the mound; but Clavigero, after a laborious investigation, comes to the conclusion, "that the first body or base of the building, was more than fifty perches long from east to west, and about forty-three in breath from north to south; the second body was about a perch less in length and breadth; the third so much less than the second, and the rest in proportion." Dr. McCulloh, relying on Gomara and Humboldt, states that the mound was faced with stone, and was 320 feet square at the base, and 120 feet high.

In the drawing just given, it will be observed that there are turn towers erected on the upper surface, and Clavigero so describes the edifice; but the learned author of Researches on American Aboriginal History, founding his opinion on Gomara and Bernal Diaz, ventures to differ from Clavigero. Diaz says there was but one, and those who read his work, in the original, will not fail to be struck with the air of accuracy and truth with which the whole story of that brave old soldier is given from beginning to end.

There is no question, however, that there was at least one tower, raised to nearly the height of fifty-six feet. It was divided into three stories, the lower one of stone and mortar; the others of wood, neatly wrought and painted. The inferior portion of this edifice was the Sanctuary; where, Diaz relates, two highly adorned altars were erected to Huitzilopotchtli and Tezcatlipoca, over which the idol images were placed in state.

Before these towers, or tower, on two vases or altars, "as high as a man," a fire was kept day and night, and its accidental extinguishment was dreaded, as sure to be followed by the wrath of Heaven.

In addition to this great Teocalli, there were forty other temples dedicated to the gods, within the area of the serpent-covered wall. There was the Tezcacalli, or "House of Mirrors," the walls of which were covered with brightly shining materials. There was the Teccixzcalli, a house adorned with shells, to which the sovereign retired at times for fasting, solitude and prayer. There were temples to Texcatlipoca, Tlaloc, and Qaetxalcoatl—the shrine of the latter being circular, while those of the others were square, "The entrance" says Clavigero, "to this sanctuary was by the mouth of an enormous serpent of stone, armed with fangs; and the Spaniards who, tempted by their curiosity, ventured to enter, afterward confessed their horror when they beheld the interior." It is said, that among these temples was one dedicated to the planet Venus; and that they sacrificed a number of prisoners, at the time of her appearance, before a huge pillar, upon which was engraved the figure of a star.

The Colleges of the priests, and their seminaries, were likewise various and perhaps numerous; "but only five are particularly known, although there must have been more, from the prodigious number of persons who were found in that place consecrated to the worship of the gods."

Besides these edifices of religious retirement and learning, there was a house of entertainment to accommodate strangers of eminence, who piously came to visit the Temple or to see the "grandeurs of the Court." There were ponds, in which the priests bathed at midnight, and many beautiful fountains, one of which was deemed holy, and only used on the most solemn festivals.

Then there were gardens where flowers and sweet-smelling herbs were raised for the decoration of the altars, and among which they fed the birds used in sacrifices to certain idols. It is said, that there was even a little wood or grove filled with "hills, rocks, and precipices," from which, upon one of their solemn festivals, the priests issued in a mimic chase.

Without entering on a more extended description of the Mexican temples, and the lives, character, and occupations of the priesthood, I will

Group From The Side Of Sacrificial Stone

But after instructing you in some degree in the history of the priest-hood and the temples, it would be improper for me to leave the subject without an account of the services to which they were both devoted.

The chief of these were the sacrifices—and in illustration of them, I have placed at the commencement of this letter, a drawing of the large circular stone now in the University of Mexico, known by the name of the "Piedra de Sacrificios," or Sacrificial Stone. It is an immense mass of basalt, nine feet in diameter and three in height, and was found in 1790, below the great square of Mexico, on the site of the Teocalli, which I have just described.

When first discovered, this stone was overturned, but, upon reversing it, carvingss in bas-relief were seen on the surface, and the sides were found to be beautifully sculptured, as will be observed in the opposite plate.

In the centre of the upper surface there is a circular cavity, from which a canal, or gutter, leads to the circumference of the cylinder and partly down its side. This, together with the sculpture, has induced most writers to believe it to have been the stone on which the priests performed their sacrifices, and that the blood of the victims flowed from it by these evident conduits. Yet other authors doubt whether it was ever appropriated to this use. It is true, that in the description of the great Temple given by the old writers, it is alleged that in front of the tower, on the summit, there was a large convex stone upon which they extended the person who was to be sacrificed; but it is highly probable that so huge a mass of rock as this,[2] could not have been borne up such intricate passages as the steps of the Teocalli, to the height of 120 feet. De Gama is of opinion that these stones were also found in the square below, in the temples, or before the altars of other deities; and, in the description of those in the temples of Huitzilopotchli and Tlaloc, Doctor Hernandez says they were "concoxes et orbiculari forma," and called "Techcatl." "Ante has" (meusulas) "aderant lapidæ orbiculari forma, quibus techcatl nomen, ubi servi, at in proæsliis capti, in horum Deorum honorem mactabantur, è quibus lapidibus in parimentum usque in infernum civi sanguinci conspiciebanteur vestigia quod etiam videbatur in casteris turribus."

With these authorities, and apparent appropriateness from the cavities already described, it is, nevertheless, the opinion of De Gama that this neither a Stone of Sacrifice, nor the Gladiatorial Stone. Such, however, is its name, and such the opinion of most persons in Mexico; and, although I should not perhaps, in justice, venture to express an opinion, yet I cannot help believing with the majority.

When we look at the sculpture at the sides, we are struck with the fitness of the adornment for sacrificial ceremonies. The Mexicans undoubtedly sacrificed the captives they had taken in battle, and the bas-relief evidently represents a conqueror and a captive. The victor's hand is raised in the act of tearing the plumes from his prisoner's crest, while the captive bows beneath the indignity, and prostrates his arms—and here let me invite the reader's attention to the great similarity of these figures and their dresses, to those delineated by Catherwood and Stephens, as having been found in Yucatan and at Palenque.[3]

*******

I will now give you some account of the Mexican Sacrifices. These were of two kinds: the common sacrifice of human victims, and the "Gladiatorial Sacrifice."

It is supposed, that neither the Toltecs nor Chechemicas permitted human sacrifices, and that it was reserved for the successors of these occupants of the Vale of Anahuac to institute the abominable practice. The history of the Aztec tribe reveals to us the fact, that it fought itself gradually to power. The Mexicans founded their Empire first among the lagunes and marshes of the lake; and it grew, by slow degrees, to the power and wealth it possessed at the period of the conquest.

When I encounter in Mexican history a monstrous fact like this, of the sacrifice to the gods of the unfortunate prisoners who had fallen into their power in battle, I am not deterred, by its enormity, from inquiring whether some secret policy may not have originated the horrid rite. The mind naturally revolts at the idea that it sprang from a mere brutal love of blood, or that a nation could, at any period of the world, have been so cruel and so inhuman!

In reviewing, then, the history of the Empire of a weak but bold and ambitious people—fighting for a foothold; becoming powerful only as it was able to inspire its enemies with terror; unable to maintain, subdue, or imprison its captives—we may ask ourselves, whether it was not rather a stroke of savage statesmanship in the Chiefs of the time, to make a merit of necessity, and a holy and religious rite of what, under other circumstances and in a later period of the world, has been considered a murder?

And such, I believe, to have been the beginning of the Mexican sacrifices. A weak people unable to control, enslave, or trust its prisoners, devoted them to the gods. But, in the progress of time, when that nation had acquired a strength equal to any emergency, this ceremony, too, had become a prescriptive usage—a traditionary and most important part of the religion itself; and thus, what in its inception was the policy of feebleness, ended in an established principle of the mythology of a powerful and even civilized Empire.

*******

Let us now proceed to consider the manner in which these sacrifices were conducted.

The usual number of priests required at the altar was six, one of whom acted as Sacrificer and the others as his assistants. The Chief of these, whose office and dignity were preeminent, assumed at every sacrifice the name of the deity to whom the oblation was made.

His dress was a red habit, like the Roman scapulary, fringed with cotton; his head was bound with a crown of green and yellow feathers; his ears were adorned with emeralds, and from his lips depended a turquoise. The other ministers at the rite were clad in white, embroidered with black; their locks bound up, their heads covered with leather thongs, their foreheads filleted with slips of paper of various colors, and their bodies dyed entirely black.

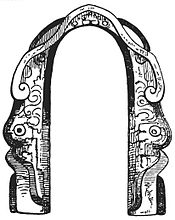

They dressed the victim in the insignia of the god to whom he was to be offered; adored him as they would have adored the divinity himself; and bore him around the city asking alms for the temple. He was then carried to the top of the temple and extended upon the stone of sacrifice. Four of the priests held his limbs, and another kept his head or neck firm with a yoke, an original of which is preserved in the Museum, and is here represented.

sacrificial yoke.

The Topiltzin, or Sacrificer, then approached with a sharp knife of obsidian.

sacrificial knife of obsidian.

He made an incision in the victim's breast; tore out his heart with his hand; offered it to the sun, and then threw it palpitating at the feet of the god.

If the idol was large and hollow, it was usual to insert the heart in its mouth with a golden spoon; and at other times it "was taken up from the ground again, offered to the idol, burned, and the ashes preserved with the greatest veneration."

"After these ceremonies," says Dr. McCulloh, "the body was thrown from the top of the temple, whence it was taken by the person who had offered the sacrifice, and carried to his house, where it was eaten by himself and friends. The remainder was burned, or carried to the royal menageries to feed the wild beasts!"

At times they offered only flowers, fruits, oblations of bread, cooked meats, (like the Chinese,) copal and gums, quails, falcons, and rabbits; but, at the feasts of some of the deities, especially every fourth year, among the Quauhtitlans, the rites were dreadfully inhuman.

Six trees were then planted in the area of the temple, and two slaves were sacrificed, from whose bodies the skin was stripped, and the thigh-bones withdrawn. On the following day, "clad in the bloody skins the thigh-bones in their hands," two of the chief priests slowly descended the steps of the temple; with dismal howlings, while the multitude assembled below shouted, "Behold our gods!"

At the base of the temple they danced to the sound of music, while the people sacrificed several thousand quails. When the oblation was terminated, the priests fastened to the tops of the trees six prisoners, who were immediately pierced with arrows. They then cut the bodies from the trees and threw them to the earth, where their breasts were torn open, and the hearts wrenched out according to the usual custom. This bloody and cruel festival was ended by a banquet, in which the priests and nobles of the city feasted on the quails and the human flesh!

The other mode of sacrifice as I have before said, was the "Gladiatorial."

gladiatorial stone.

The stone, of which the foregoing plate is an outline, was, (like the Sacrificial Stone,) found in the great square of Mexico, where it still lies buried, for want of the trifling sum required to disinter it once more, and place it in the Museum.

When the square was undergoing repairs, some years past, this monument was discovered a short distance beneath the surface. Mr. Gondra endeavored to have it removed, but the Government refused to incur the expense; and its dimensions, as he tells me, being exactly those of the Sacrificial Stone, viz. nine feet by three, he declined undertaking it on his own account. Yet, anxious to preserve, if possible, some record of the carving with which it was covered, (especially as that carving was painted with yellow, red, green, crimson, and black, and the colors still quite vivid,) he had a drawing made, of which the sketch in this work is a fac-simile.

Mr. Gondra believes it to have been the Gladiatorial Stone, placed perhaps opposite the great Sacrificial Stone, at the base of the Teocalli. This, however, would not agree with the accounts of some of the old writers, who, although they agree that this stone was circular, as is signified by its name, (Temalacatl) yet state that its surface was smooth, and had in its centre a bore or bolt, to which the captive was attached, as will be hereafter described.

The figures represented on the stone in relief, are evidently those of warriors armed, and ready for the strife; and I have thought it proper to give the picture of it to the public, for the first time, (subject, of course, to all critical observations,) with the hope that if it be not the Gladiatorial Stone, those who are more learned in Mexican antiquity, may some day discover what it really is. It is certainly remarkable for the colors, which are yet fresh; and for the figure of the "open hand," which is sculptured on a shield and between the legs of some of the figures of the groups at the sides. This "open hand" was a figure found by Mr. Stephens, in almost every temple he visited, during his recent explorations of Yucatan.[4]

*******

The Gladiatorial Sacrifice—the most noble of them all—was reserved alone for captives renowned for courage.

In an area, near the temple, large enough to contain a vast crowd of spectators, upon a raised terrace eight feet from the wall, was a circular stone, "resembling a mill-stone," says Clavigero,[5] "which was three feet high, well polished, and with figures cut on it." On this the prisoner was placed, tied by one foot, and armed with a small sword and shield, while a Mexican soldier or officer, better armed and accoutred, mounted to encounter him in deadly conflict. The efforts of the brave prisoner were of course redoubled to save his life and fame, as were those of the Mexican, whose countrymen gazed with anxiety upon him as the vindicator of their nation's skill and glory. If the captive was vanquished in the combat, he was immediately borne "to the altar of common sacrifice," and his heart torn out, while the multitude applauded the victor, who was rewarded by his sovereign. Some historians declare, that if the prisoner vanquished one combatant he was free; but Cortéz tells us that he was not granted his life and liberty until he had overcome six. It was then, only, that the spoils taken from him in war were restored, and he was allowed to return to his native land.

It is related that once when the chief lord of the Cholulans had become captive to the Huexotzincas, he overthrew, in the gladiatorial fight, seven of the foes who came to encounter him; and being thus entitled to his fortune and liberty, he was nevertheless slain by his enemies, who feared so valiant and fortunate a chieftain. By this perfidious act, the nation rendered itself eternally infamous among all the rest.

The number of the victims, with whose blood the Teocallis of Mexico were in this manner, and in the "common sacrifice" annually deluged, is not precisely known. Clavigero thinks 20,000 nearer the truth than any of the other relations; but the question may well be asked. Whence came the subjects to glut the gods with these periodical sacrifices? It seems that no land could furnish them without depopulation.

In the consecration of the Great Temple, however, which, it is related, took place in the year 1486, under the predecessor of Montezuma, there appears no doubt among those who have most carefully examined the matter, that its walls and stairways, its altars and shrines, were baptized and consecrated with the blood of more than sixty thousand victims. "To make these horrible offerings" says the historian, "with more show and parade, they ranged the prisoners in two files, each a mile and a half in length, which began in the woods of Tacuba and Iztpalapan, and terminated at the Temple, where, as soon as the victims arrived, they were sacrificed."

Six millions of people, it is said, attended, and if this is not an exaggeration of tradition, there can be no wonder whence the captives sprung, or why the rite of sacrifice was instituted. If anything can pardon the cupidity and blood-thirstiness of the Christian Spaniard, for his overthrow of the Temple and Monarchy of Mexico, it is to be found in the cruel murders which were perpetrated, by the immolation of thousands of immortal beings to a blind and bloody idolatry.

- ↑ I give the description of Clavigero and Dr. McCulloh, founded on the authority of Cortéz's Letters to Charles V. Bernal Diaz, Sahagum, and the Anonymous Conqueror.

- ↑ Nine feet in diameter by three feet high.

- ↑ Vide Stephens's Yucatan, vol. i, pp 428 and 429, and the plates opposite them.

- ↑ I have not caused the figures of the sides of this stone to be engraved in the present edition.

- ↑ Clavigero, vol. ii. 299.