phoniques' (Concerts du Châtelet, Nov. 25, 1877), and his Overture 'Fritiof' (Do. Feb. 13, 1881). The last of these, a work full of life and accent, ranks, together with his two small operas, among his best compositions. He possesses a full knowledge of all the resources of his art, but little originality or independence of style. For some time he was maître de chapelle at the Madeleine, and is now organist there, having replaced Saint-Säens in 1877. He succeeded Elwart as professor of harmony at the Conservatoire, in 1871, and in 1883 was decorated with the Legion of Honour.

DUBOURG, G. Add that he died at Maidenhead, April 17, 1882.

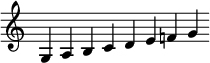

DULCIMER. P. 468 b. Add that English dulcimers have ten long notes of brass wire in unison strings, four or five in number, and ten shorter notes of the same. The first series, struck with hammers to the left of the right-hand bridge, is tuned

the F being natural. The second series, struck to the right of the left-hand bridge, is

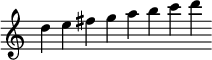

the F being again natural. The remainder of the latter series, struck to the left of the left-hand bridge, gives

This tuning has prevailed in other countries and is old. Chromatic tunings are modern and apparently arbitrary.

DULCKEN, Mme. Line 3, correct date of birth to March 29.

DUN, Finlay, born in Aberdeen, Feb. 24, 1795, viola player, teacher of singing, musical editor and composer, in Edinburgh; studied abroad under Baillot, Crescentini, and others. He wrote, besides two symphonies (not published) Solfeggi, and Scale Exercises for the voice (1829), edited, with Professor John Thomson, Paterson's Collection of Scottish Songs, and took part also with G. F. Graham and others in writing the pianoforte accompaniments and symphonies for Wood's Songs of Scotland; he was editor also of other Scotch and Gaelic Collections. Dun was a master of several living and dead languages, and seems altogether to have been a very accomplished man. He died Nov. 28, 1853.

DUNSTABLE,[1] John, musician, mathematician, and astrologer, was a native of Dunstable, in Bedfordshire. Of his life absolutely nothing is known, but he has long enjoyed a shadowy celebrity as a musician, mainly owing to a passage in the Prohemium to the 'Proportionale' of Johannes Tinctoris (1445–1511). The author, after mentioning how the institution of Royal choirs or chapels encouraged the study of music, proceeds: 'Quo fit ut hac tempestate, facultas nostræ musices tarn mirabile susceperit incrementum quod ars nova esse videatur, cujus, ut ita dicam, novæ artis fons et origo, apud Anglicos quorum caput Dunstaple exstitit, fuisse perhibetur, et huic contemporanei fuerunt in Gallia Dufay et Binchois quibus immediate successerunt moderni Okeghem, Busnois, Regis et Caron, omnium quos audiverim in compositione praestantissimi. Haec eis Anglici nunc (licet vulgariter jubilare, Gallici vero cantare dicuntur) veniunt conferendi. Illi etenim in dies novos cantus novissime inveniunt, ac isti (quod miserrimi signum est ingenii) una semper et eadem compositione utuntur.' (Coussemaker, 'Scriptores,' vol. iv. p. 154.) Ambros ('Geschichte der Musik,' ii. pp. 470–1) has shown conclusively how this passage has been gradually misconstrued by subsequent writers, beginning with Sebald Heyden in his 'De Arte Canendi' (1540), until it was boldly affirmed that Dunstable was the inventor of Counterpoint! Ambros also traces a still more absurd mistake, by which Dunstable was changed into S. Dunstan; this was the invention of Franz Lustig, who was followed by Printz, Marpurg, and other writers. It might have been considered that the claim of any individual to be the 'inventor' of Counterpoint would need no refutation. Counterpoint, like most other branches of musical science, can have been the invention of no single man, but the gradual result of the experiments of many. Tinctoris himself does not claim for Dunstable the position which later writers wrongly gave him. It will be noticed that the 'fons et origo' of the art is said to have been in England, where Dunstable was the chief musician; and though Tinctoris is speaking merely from hearsay, yet there is nothing in his statement so incredible as some foreign writers seem to think. So long as the evidence of the Rota 'Sumer is y-cumen in' is unimpeached, it must be acknowledged that there was in England, in the early 13th century, a school of musicians which was in advance of anything possessed by the Netherlands at the same period. Fortunately the evidence for the date of the 'Rota' is so strong that it cannot be damaged by statements of historians who either ascribe it to the 15th century or ignore it altogether. Within the last few years an important light has been thrown upon the relation of Dunstable to the Netherlands musicians Dufay and Binchois, by the discovery (Monatshefte für Musikgeschichte, 1884, p. 26) that Dufay died in 1474, and not, as had been hitherto supposed, some twenty years before Dunstable. Binchois did not die until 1460, so it is clear that, though the three musicians were for a time contemporaries, yet Tinctoris was right in classing the Englishman as the head of a school which actually preceded the Netherlanders and Burgundians.

Dunstable's fame was certainly great, though short-lived. He is mentioned in a manuscript preserved in the Escorial (c. iii. 23),

- ↑ The name is spelt by early authors Dunstaple.