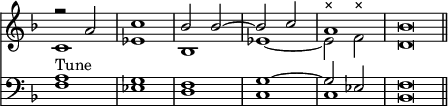

by Day in 1560,—the composers to whom the publisher had recourse for this undertaking are all, except one,[1] otherwise unknown. Nor is their music, though generally respectable and sometimes excellent, of a kind that requires any detailed description: it will be sufficient to mention a few of its most noticeable characteristics, interesting chiefly from the insight they afford into the practice of the average proficient at this period. The character of these compositions in most cases is much the same as that of the simple settings of the French Psalter by Goudimel and Claude le Jeune; the parts usually moving together, and the tenor taking the tune. The method of Causton, however, differs in some respects from that of his associates: he is evidently a follower of Tye; showing the same tendency towards florid counterpoint, and often indeed using the same figures. He is, as might be expected, very much Tye's inferior in invention, and moreover still retains some of the objectionable collisions, inherited by the school of this period from the earlier descant, which Tye had refused to accept.[2] Brimle offends in the same way, but to a far greater extent: indeed, unless he has been cruelly used by the printer, he is sometimes unintelligible. In one of his compositions, for instance, having to accommodate his accompanying voices to a difficult close in the melody, he has written as follows:—[3]

The difficulty arising from the progression of the melody in this passage was one that often presented itself during the process of setting the earliest versions of the church tunes. It arose whenever the melody, in closing, passed by the interval of a whole tone from the seventh of the scale to the final. When this happened, the final cadence of the mode was of course impossible, and some sort of expedient became necessary. Since, however, no substitute for the proper close could be really satisfactory because, no matter how cleverly it might be treated, the result must necessarily be ambiguous—in all such cases the melody was sooner or later altered. As these expedients do not occur in subsequent Psalters, two other specimens are here given of a more rational kind than the one quoted above.

Both Parsons[5] and Hake appear to have been excellent musicians. The style of the former is somewhat severe, sometimes even harsh, but always strong and solid. In the latter we find more sweetness; and it is characteristic of him that, more frequently than the others, he makes use of the soft harmony of the imperfect triad in its first inversion. It should be mentioned that of the 17 tunes set by him in this collection, 7 were church tunes, and 10 had previously appeared in Crespin's edition of Sternhold, and had afterwards been dropped. His additions, therefore, were none of them original. One other point remains to be noticed. Modulation, in these settings, is extremely rare; and often, when it would seem—to modern ears at least—to be irresistibly suggested by the progression of the melody, the apparent ingenuity with which it has been avoided is very curious. In the tune given to the 22nd Psalm, for instance, which is in Mode XIII (final, C), the second

- ↑ Causton, a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, had been a contributor to 'Certayne notes.'

- ↑ He frequently converts passing discords into discords of percussion, by repeating the bass note; and his ear, it seems, could tolerate the prepared ninth at the distance of a second, when it occurred between inner parts.

- ↑ This passage, however, will present nothing extraordinary to those who may happen to have examined the examples, taken from Risby, Pigott, and others, in Morley's 'Plaine and Easle Introduction to Practicall Musick.' From those examples it appears that the laws which govern the treatment of discords were not at all generally understood by English musicians, even as late as the beginning of Henry the Eighth's reign: it is quite evident that discords (not passing) were not only constantly taken unprepared, but, what is more strange, the discordant note was absolutely free in its progression. It might either rise or fall at pleasure; it might pass, by skip or by degree, either to concord or discord; or it might remain to become the preparation of a suspended discord. And this was the practice of musicians of whom Morley says that 'they were skilful men for the time wherein they lived.'

- ↑ In Este's psalter the tune of No. 1 has already been altered, in order to make a true final close possible, in the manner shown below. The tune containing No. 2 does not occur again, but here also an equally simple alteration brings about the desired result.

1.W. Cobbold.

2.

2.

- ↑ W. Parsons must not be confounded with R. Parsons, a well-known composer of this period. J. Hake may possibly have been the 'Mr. Hake,' a singing man of Windsor, whose name was mentioned by Testwoode in one of the scoffing speeches for which he was afterwards tried (with Merbecke and another) and executed.