equally distributed on either side of the bridge. The neck requires to be lengthened in the same proportion; hence the stop becomes appreciably longer. The true long Strads' are remarkable for power of tone, but are for the above reason less easily handled: and hence the pattern never came into general use. Some, if not all of them, were probably made on the 'SL' (Stretto Lungo)(narrow long) mould of 1691: one very fine specimen, formerly in the possession of Lord Falmouth, is dated 1692. The 'SL' pattern was occasionally used by the maker in his mature years, but is less frequent after 1700.

The nineties were with Stradivari a decade of bold experiment in other respects. Sometimes he altered the curves of the back and belly; occasionally he innovated in the thicknesses, some of his experiments, as more than one purchaser of a handsome and unspoiled violin knows to his cost, being sufficiently unfortunate. He made some violins with bellies so thin that they are useless for the higher pitch and increased pressure of modern playing, and must either be fortified with new wood or laid on the shelf as curiosities. These various experiments enabled the maker to fix definitely the principles on which the fiddles of his third and best period (1698–1728) are designed.

This third period includes the greater part of the known instruments of Stradivari, and these are in all respects his best. The culminating point of his work may be fixed at the year 1714, which is the date of the celebrated 'Dolphin' Stradivari, once the property of M. Alard, afterwards of Mr. Adam. 'From about 1700,' writes Mr. Hart, p. 131, 'his instruments show to us much of what follows later. The outline is changed, but the curves blending into one another are beautiful in the extreme. The corners are treated differently. The wood used for the backs and sides is most handsome, having a broad curl. The scrolls are of bold conception, and finely executed.' It must be noted, however, that the differences of construction between this third and best period, and the preceding, are minute in the extreme. The modelling is much the same, the size and general design remain unaltered. Stradivari, in fact, kept the actual moulds (forme) of the preceding period constantly in use. It is true that he added new ones to his stock, e.g. that dated 1705 above mentioned. But it is obvious that his old 'B' (basso, flat) moulds were constantly in use: the majority of the violins of this last period seem to have been made from at most two or three moulds. The rapidity of his production was astonishing. In 1702, as we learn from the MSS. of Desiderio Arisi, he made two violins and a violoncello by order of the Governor of Cremona, to be sent as presents to the Duke of Alba. In 1707 the Marquis Desiderio Cleri sent by order of Charles III. of Spain a commission to Stradivari to make six violins, two tenors, and one violoncello for the royal orchestra. In the same year he made for the Countess Cristina Visconti a new viola da gamba alla gobba. The cartridge patterns for the neck of this he put away thus labelled: 'Musura del manico del Violoncello Ordinario, manicho della longezza della Viola della Signora Cristina Visconti fatta in 1707.' From this it would appear that he considered this viola da gamba neck equally adapted to the ordinary violoncello, from which it would follow that the body was of the size of an ordinary violoncello, or considerably larger than the ordinary viola da gamba. In 1716 he made new models for a violoncello (Della Valle Collection, no. 16), perhaps the same which in this year, according to the Arisi MSS., he made for the Duke of Modena. In the same year he made a twelve-stringed viola d'amore (six gut strings, and six wire strings), the pattern of which he inscribed 'Modelli della Viola d'Amore a 12 Corde fatti nell mese di Cienaio dell' anno Bisestile mdccxvi.' This is a choice specimen of Stradivari's spelling: by 'Cienaio' he means 'Gennaio,' or January. A choicer one still, in which the grammar rivals the spelling, is the inscription on the patterns of some instrument made for the Marquis Carbonelli: 'Qui dentro questi desingni che sono qui dentro sforati sono quelli che se fatto al Ill'mo. Sig. Marchese Carbonelli di Mantova' (Delia Valle Collection, no. 27).[1] In 1720 Stradivari made a concerto of instruments (probably two violins, two tenors, and a violoncello), which he intended as a present for the King of Spain on the occasion of his passing through Cremona. He was dissuaded from executing this intention, and the instruments remained in his possession.

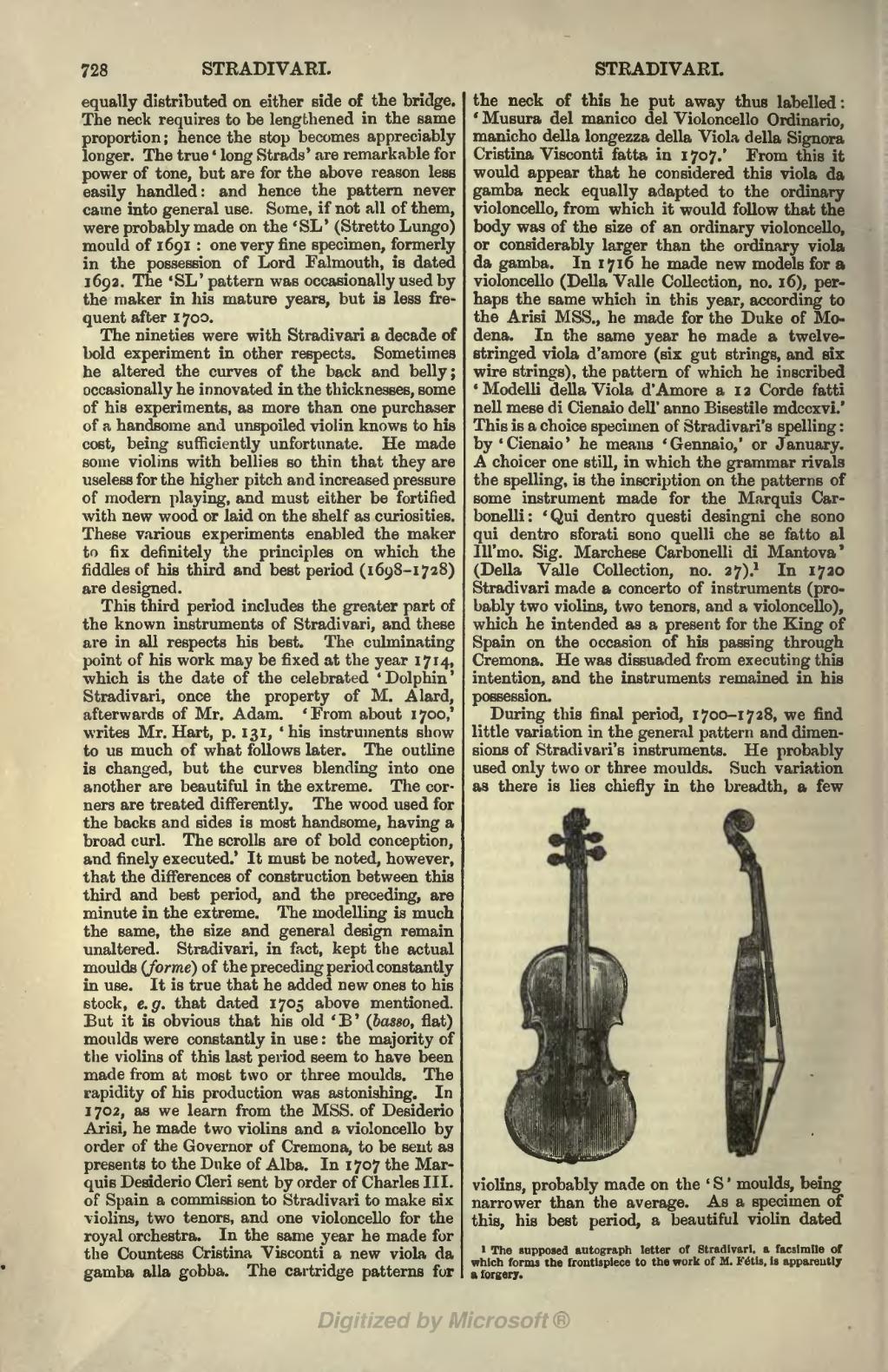

During this final period, 1700–1728, we find little variation in the general pattern and dimensions of Stradivari's instruments. He probably used only two or three moulds. Such variation as there is lies chiefly in the breadth, a few violins, probably made on the 'S' moulds, being narrower than the average. As a specimen of this, his best period, a beautiful violin dated

During this final period, 1700–1728, we find little variation in the general pattern and dimensions of Stradivari's instruments. He probably used only two or three moulds. Such variation as there is lies chiefly in the breadth, a few violins, probably made on the 'S' moulds, being narrower than the average. As a specimen of this, his best period, a beautiful violin dated

- ↑ The supposed autograph letter of Stradivari, a facsimile of which forms the frontispiece to the work of M. Fétis. is apparently a forgery.