Part-writing. Neither in Harmony nor in Melody was the employment of a Chromatic Interval permitted, in the Strict Counterpoint of the 16th century.[1] The new School permitted the leap of the Augmented Second, the Diminished Fourth, and even the Diminished Seventh; and, by analogy, the leap of the Tritonus, and the False Fifth, which, though Diatonic Intervals, are strongly dissonant. The same intervals and other similar ones were also freely employed in harmonic combination; for the excellent reason that, with instrumental aid, they were perfectly practicable, and exceedingly effective.[2]

These new conditions led, step by step, to the promulgation of an entirely new code of laws, which, taking the rules of Strict Counterpoint as their basis, added to or departed from them, whenever, and only whenever, the new conditions rendered such changes necessary or desirable.

The new laws, like those of the older code, were at first entirely empirical. Composers wrote what they found effective and beautiful, without being able to account, upon scientific principles, for the good effect produced. It was not until Rameau first called attention, in the year 1722, to the roots of chords, and the difference between fundamental and inverted harmonies,[3] that any serious attempt was made to account for the prescribed progressions upon scientific principles, or that the essential distinction between the so-called 'vertical' and 'horizontal' methods was satisfactorily demonstrated:[4] and, even then, the truth was only arrived at, after long and laborious investigation.[5]

We shall best understand the points of difference between the two systems by referring to the general laws of Strict Counterpoint, as set forth in vol. iii. p. 741–744.

The 'Five Orders' of Strict Counterpoint are, theoretically, retained in Free Part-writing, though, in practice, composers very rarely write continuous passages in any other than the Fifth Order,[6] which includes the four preceding ones, and, in the new style, admits of infinite variety of rhythm.

The four Cardinal Rules remain in force, though their stringency is slightly modified, in their relation to 'Hidden Consecutives.' In one respect, however, the severity of the law is increased. In Strict Counterpoint, there is no rule forbidding the employment of Consecutive Fifths by contrary motion;[7] while, in the Free Style, the progression is severely censured.

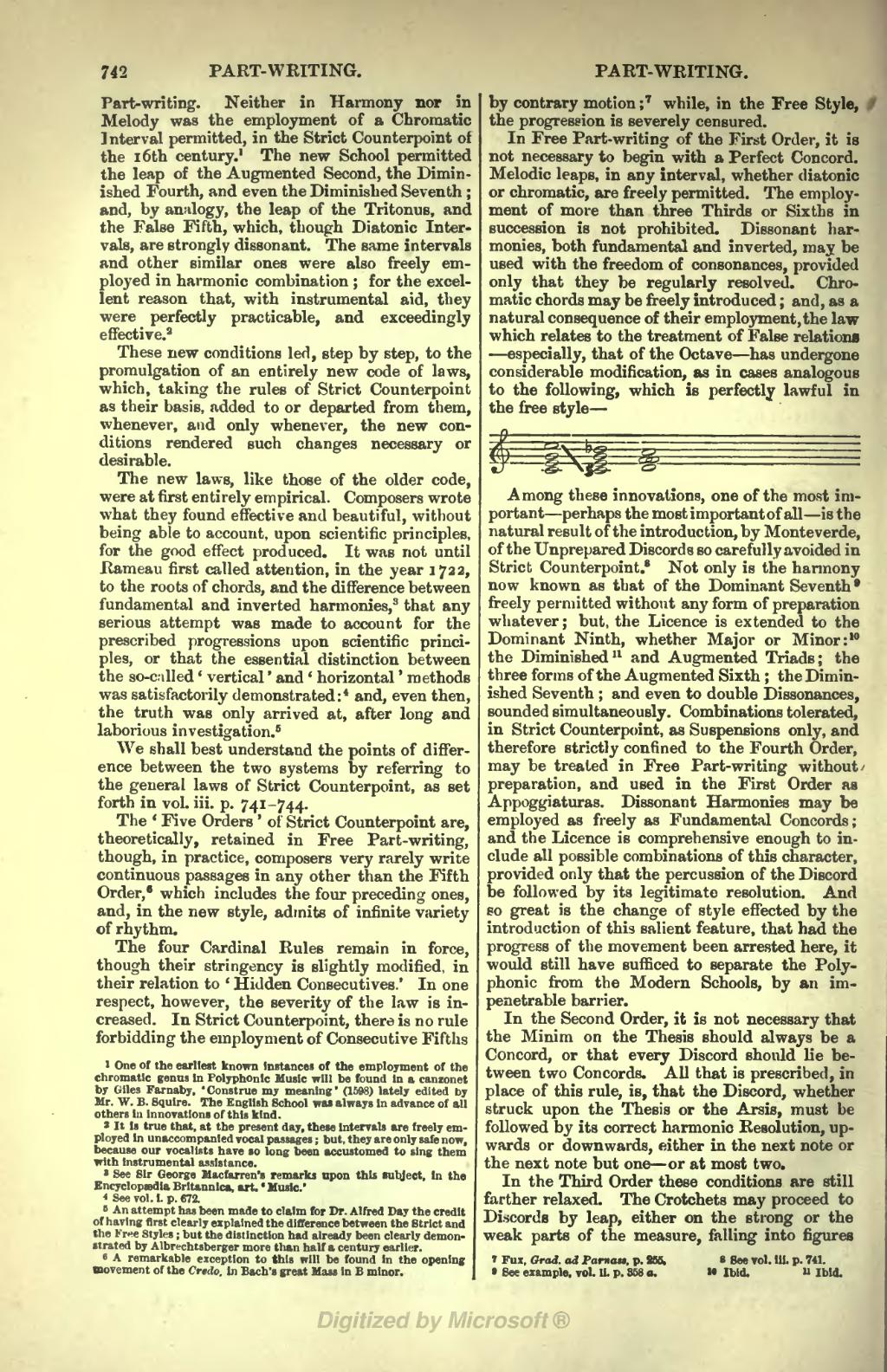

In Free Part-writing of the First Order, it is not necessary to begin with a Perfect Concord. Melodic leaps, in any interval, whether diatonic or chromatic, are freely permitted. The employment of more than three Thirds or Sixths in succession is not prohibited. Dissonant harmonies, both fundamental and inverted, may be used with the freedom of consonances, provided only that they be regularly resolved. Chromatic chords may be freely introduced; and, as a natural consequence of their employment, the law which relates to the treatment of False relations—especially, that of the Octave—has undergone considerable modification, as in cases analogous to the following, which is perfectly lawful in the free style—

Among these innovations, one of the most important—perhaps the most important of all—is the natural result of the introduction, by Monteverde, of the Unprepared Discords so carefully avoided in Strict Counterpoint.[8] Not only is the harmony now known as that of the Dominant Seventh[9] freely permitted without any form of preparation whatever; but, the Licence is extended to the Dominant Ninth, whether Major or Minor:[10] the Diminished[11] and Augmented Triads; the three forms of the Augmented Sixth; the Diminished Seventh; and even to double Dissonances, sounded simultaneously. Combinations tolerated, in Strict Counterpoint, as Suspensions only, and therefore strictly confined to the Fourth Order, may be treated in Free Part-writing without preparation, and used in the First Order as Appoggiaturas. Dissonant Harmonies may be employed as freely as Fundamental Concords; and the Licence is comprehensive enough to include all possible combinations of this character, provided only that the percussion of the Discord be followed by its legitimate resolution. And so great is the change of style effected by the introduction of this salient feature, that had the progress of the movement been arrested here, it would still have sufficed to separate the Polyphonic from the Modern Schools, by an impenetrable barrier.

In the Second Order, it is not necessary that the Minim on the Thesis should always be a Concord, or that every Discord should lie between two Concords. All that is prescribed, in place of this rule, is, that the Discord, whether struck upon the Thesis or the Arsis, must be followed by its correct harmonic Resolution, upwards or downwards, either in the next note or the next note but one—or at most two.

In the Third Order these conditions are still farther relaxed. The Crotchets may proceed to Discords by leap, either on the strong or the weak parts of the measure, falling into figures

- ↑ One of the earliest known instances of the employment of the chromatic genus in Polyphonic Music will be found in a canzonet by Giles Farnaby, 'Construe my meaning' (1598) lately edited by Mr. W. B. Squire. The English School was always in advance of all others in innovations of this kind.

- ↑ It is true that, at the present day, these intervals are freely employed in unaccompanied vocal passages; but, they are only safe now, because our vocalists have to long been accustomed to sing them with instrumental assistance.

- ↑ See Sir George Macfarren's remarks upon this subject, in the Encyclopædia Britannica, art. 'Music.'

- ↑ See vol.1, p. 672.

- ↑ An attempt has been made to claim for Dr. Alfred Day the credit of having first clearly explained the difference between the Strict and the Free Styles; but the distinction had already been clearly demonstrated by Albrechtsberger more than half a century earlier.

- ↑ A remarkable exception to this will be found in the opening movement of the Credo in Bach's great Mass in B minor.

- ↑ Fux. Grad. ad Parnass. p. 266.

- ↑ See vol. iii. p. 741.

- ↑ See example, vol. ii. p. 358a.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.