cessary to have an instrument which is capable of producing all the combinations of notes used in harmony, of sustaining the sound as long as may be desired, and of distinguishing clearly between just and tempered intonation. These conditions are not fulfilled by the pianoforte; for, owing to the soft quality of its tones, and the quickness with which they die away, it does not make the effects of temperament acutely felt. The organ is more useful for the purpose, since its full and sustained tones, especially in the reed stops, enable the ear to perceive differences of tuning with greater facility. The harmonium is superior even to the organ for illustrating errors of intonation, being less troublesome to tune and less liable to alter in pitch from variation of temperature or lapse of time.

By playing a few chords on an ordinary harmonium and listening carefully to the effect, the student will perceive that in the usual mode of tuning, called Equal Temperament, only one consonant interval has a smooth and continuous sound, namely the Octave. All the others are interrupted by beats, that is to say, by regularly recurring throbs or pulsations, which mark the deviation from exact consonance. For example, the Fifth and Fourth, as at (x), are each made to give about one beat per second. This error is so slight as to be hardly worth notice, but in the Thirds and Sixths the case is very different. The Major Third, as at (y), gives nearly twelve beats per second: these are rather strong and distinct, and become still harsher if the interval is extended to a Tenth or a Seventeenth. The Major Sixth, as at (z), gives about ten beats per second, which are so violent, that this interval in its tempered form barely escapes being reckoned as a dissonance.

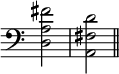

The Difference-Tones resulting from these tempered chords are also thrown very much out of tune, and, even when too far apart to beat, still produce a disagreeable effect, especially on the organ and the harmonium. [Resultant Tones.] The degree of harshness arising from this source varies with the distribution of the notes; the worst results being produced by chords of the following types—

By playing these examples, the student will obtain some idea of the alteration which chords undergo in equal temperament. To understand it thoroughly, he should try the following simple experiment. 'Take an ordinary harmonium and tune two chords perfect on it. One is scarcely enough for comparison. To tune the triad of C major, first raise the G a very little, by scraping the end of the reed, till the Fifth, C—G, is dead in tune. Then flatten the Third E, by scraping the shank, till the triad C—E—G is dead in tune. Then flatten F till F—C is perfect, and A till F—A—C is perfect. The notes used are easily restored by tuning to their Octaves. The pure chords obtained by the above process offer a remarkable contrast to any other chords on the instrument.'[1] It is only by making oneself practically familiar with these facts, that the nature of temperament can be clearly understood, and its effects in the orchestra or in accompanied singing, properly appreciated.

Against its defects, equal temperament has one great advantage which specially adapts it to instruments with fixed tones, namely its extreme simplicity from a mechanical point of view. It is the only system of tuning which is complete with twelve notes to the Octave. This result is obtained in the following manner. If we start from any note on the keyboard (say G♭), and proceed along a series of twelve (tempered) Fifths upwards and seven Octaves downwards, thus—

we come to a note (F♯) identical with our original one (G♭). But this identity is only arrived at by each Fifth being tuned somewhat too flat for exact consonance. If, on the contrary, the Fifths were tuned perfect, the last note of the series (F♯) would be sharper than the first note (G♭) by a small interval called the 'Comma of Pythagoras,' which is about one-quarter of a Semitone. Hence in equal temperament, each Fifth ought to be made flat by one-twelfth of this Comma; but it is extremely difficult to accomplish this practically, and the error is always found to be greater in some Fifths than in others. If the theoretic conditions which the name 'equal temperament' implies, could be realised in the tuning of instruments, the Octave would be equally divided into twelve Semitones, six Tones, or three Major Thirds. Perfect accuracy, indeed, is impossible even with the best-trained ears, but the following rule, given by Mr. Ellis, is much less variable in its results than the ordinary process of guesswork. It is this:—'make all the Fifths which lie entirely within the Octave middle c′ to treble c″ beat once per second; and make those which have their upper notes above treble c″ beat three times in two seconds. Keeping the Fifth treble f′ and treble c″ to the last, it should beat once in between one and two seconds.'[2] In ordinary practice, however, much rougher approximations are found sufficient.

The present system of tuning, by equal temperament, was introduced into England at a comparatively recent date. In 1854 organs