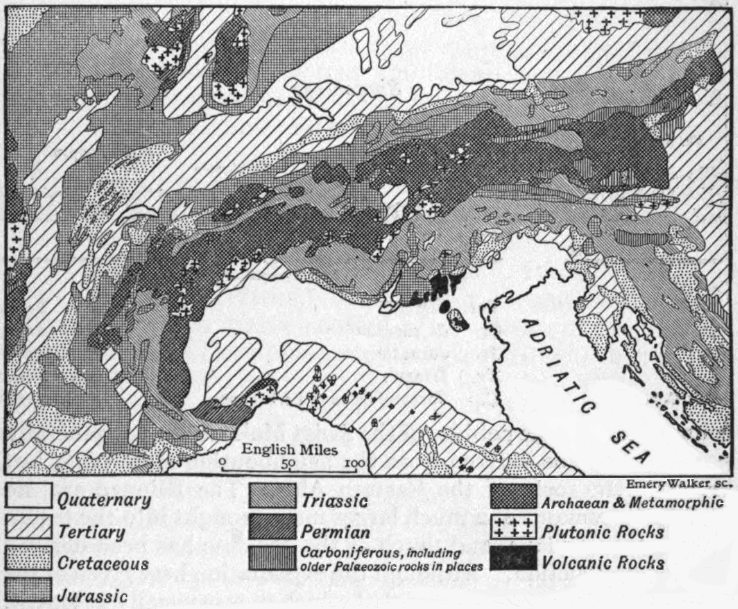

and the folding is more intense on the Bavarian side than on the Italian, the folds often leaning over towards the north. The Tertiary zone of the northern border is of especial significance and is remarkable for its extent and uniformity. It is divided longitudinally into an outer zone of Molasse and an inner zone of Flysch. The line of separation is very clearly defined; nowhere does the Molasse pass beyond it to the south and nowhere does the Flysch extend beyond it to the north. The Molasse, in the neighbourhood of the mountains, consists chiefly of conglomerates and sandstones, and the Flysch consists of sandstones and shales; but the Molasse is of Miocene and Oligocene age, while the Flysch is mainly Eocene. The relations of the two series are never normal. Along the line of contact, which is often a fault, the oldest beds of the Molasse crop out, and they are invariably overturned and plunge beneath the Flysch. A few miles farther north these same beds rise again to the surface at the summit of an anticlinal which runs parallel to the chain. Beyond this point all signs of folding gradually cease and the beds lie flat and undisturbed.

The Flysch is an extraordinarily thick and uniform mass of sandstones and shales with scarcely any fossils excepting fucoids. It is intensely folded and is constantly separated from the Mesozoic zone by a fault. Throughout the whole extent of the Eastern Alps it is strictly limited to the belt between this fault and the marginal zone of Molasse. Eocene beds, indeed, penetrate farther within the chain, but these are limestones with nummulites or lignite-bearing shales and have nothing in common with the Flysch. But although the Flysch is so uniform in character, and although it forms so well-defined a zone, it is not everywhere of the same age. In the west it seems to be entirely Eocene, but towards the east intercalated beds with Inoceramus, &c., indicate that it is partly of Cretaceous age. It is, in fact, a facies and nothing more. The most probable explanation is that the Flysch consists of the detritus washed down from the hills upon the flanks of which it was formed. It bears, indeed, very much the same relation to the Alps that the Siwalik beds of India bear to the Himalayas.

The Mesozoic belt of the Bavarian and Austrian Alps consists mainly of the Trias, Jurassic and Cretaceous beds playing a comparatively subordinate part. But between the Trias of the Eastern Alps and the Trias of the region beyond the Alpine folds there is a striking contrast. North of the Danube, in Germany as in England, red sandstones, shales and conglomerates predominate, together with beds of gypsum and salt. It was a continental formation, such as is now being formed within the desert belt of the globe. Only the Muschelkalk, which does not reach so far as England, and the uppermost beds, the Rhaetic, contain fossils in any abundance. The Trias of the Eastern Alps, on the other hand, consists chiefly of great masses of limestone with an abundant fauna, and is clearly of marine origin. The Jurassic and Cretaceous beds also differ, though in a less degree, from those of northern Europe. They consist largely of limestone; but marls and sandstones are by no means rare, and there are considerable gaps in the succession indicating that the region was not continuously beneath the sea. Tithonian fossils, characteristic of southern Europe, occur in the upper Jurassic, while the Gosau beds, belonging to the upper Cretaceous, contain many of the forms of the Hippuritic sea. Nevertheless, the difference between the deposits on the two sides of the chain shows that the central ridge was dry land during at least a part of the period.

The central zone of crystalline rock consists chiefly of gneisses and schists, but folded within it is a band of Palaeozoic rocks which divides it longitudinally into two parts. Palaeozoic beds also occur along the northern and southern margins of the crystalline zone. The age of a great part of the Palaeozoic belts is somewhat uncertain, but Permian, Carboniferous, Devonian and Silurian fossils have been found in various parts of the chain, and it is not unlikely that even the Cambrian may be represented.

The Mesozoic belt of the southern border of the chain extends from Lago Maggiore eastwards. Jurassic and Cretaceous beds play a larger part than on the northern border, but the Trias still predominates. On the west the belt is narrow, but towards the east it gradually widens, and north of Lago di Garda its northern boundary is suddenly deflected to the north and the zone spreads out so as to include the whole of the Dolomite mountains of Tirol. The sudden widening is due to the great Judicaria fault, which runs from Lago d’Idro to the neighbourhood of Meran, where it bends round to the east. The throw of this fault may be as much as 2000 metres, and the drop is on its south-east side, i.e. towards the Adriatic. It is probable, indeed, that the fault took a large share in the formation of the Adriatic depression. On the whole, the Mesozoic beds of the southern border of the Alps point to a deeper and less troubled sea than those of the north. Clastic sediments are less abundant and there are fewer breaks in the succession. The folding, moreover, is less intense; but in the Dolomites of Tirol there are great outbursts of igneous rock, and faulting has occurred on an extensive scale.

West of a line which runs from Lake Constance to Lago Maggiore the zones already described do not continue with the same simplicity. The zone of the Molasse is little changed, but the Flysch is partly folded in the Mesozoic belt and no longer forms an absolutely independent band. The Trias has almost disappeared, and what remains is Swiss Alps.not of the marine type characteristic of the Eastern Alps but belongs rather to the continental facies which occurs in Germany and France. Jurassic and Cretaceous beds form the greater part of the Mesozoic band. On the southern side of the chain the Mesozoic zone disappears entirely a little west of Lago Maggiore and the crystalline rocks rise directly from the plain.

Perhaps the strangest problem in the whole of Switzerland is that presented by the so-called Klippen. Within the Alps, when normally developed, we may trace the individual folds for long distances and observe how they arise, increase and die out, to be replaced by others of similar direction. But at times, within or on the border of the northern Eocene trough, the continuity of the folds is suddenly broken by mountain masses of quite different constitution. These are the Klippen, and they are especially important in the Chablais and between the Lakes of Geneva and Thun. Not only is the folding of the Klippen wholly independent of that of the zone in which they lie, but the rocks which form them are of foreign facies. They consist chiefly of Jurassic and Triassic beds, but it is the Trias and the Jura of the Eastern Alps and not of Switzerland. Moreover, although they interrupt the folding of the zone in which they occur, they do not disturb it: they do not, in fact, rise through the zone, but lie upon it like unconformable masses—in other words, they rest upon a thrust-plane. Whence they have come into their present position is by no means clear; but the character of the beds which form them indicates a distant origin. It is interesting to note, in this