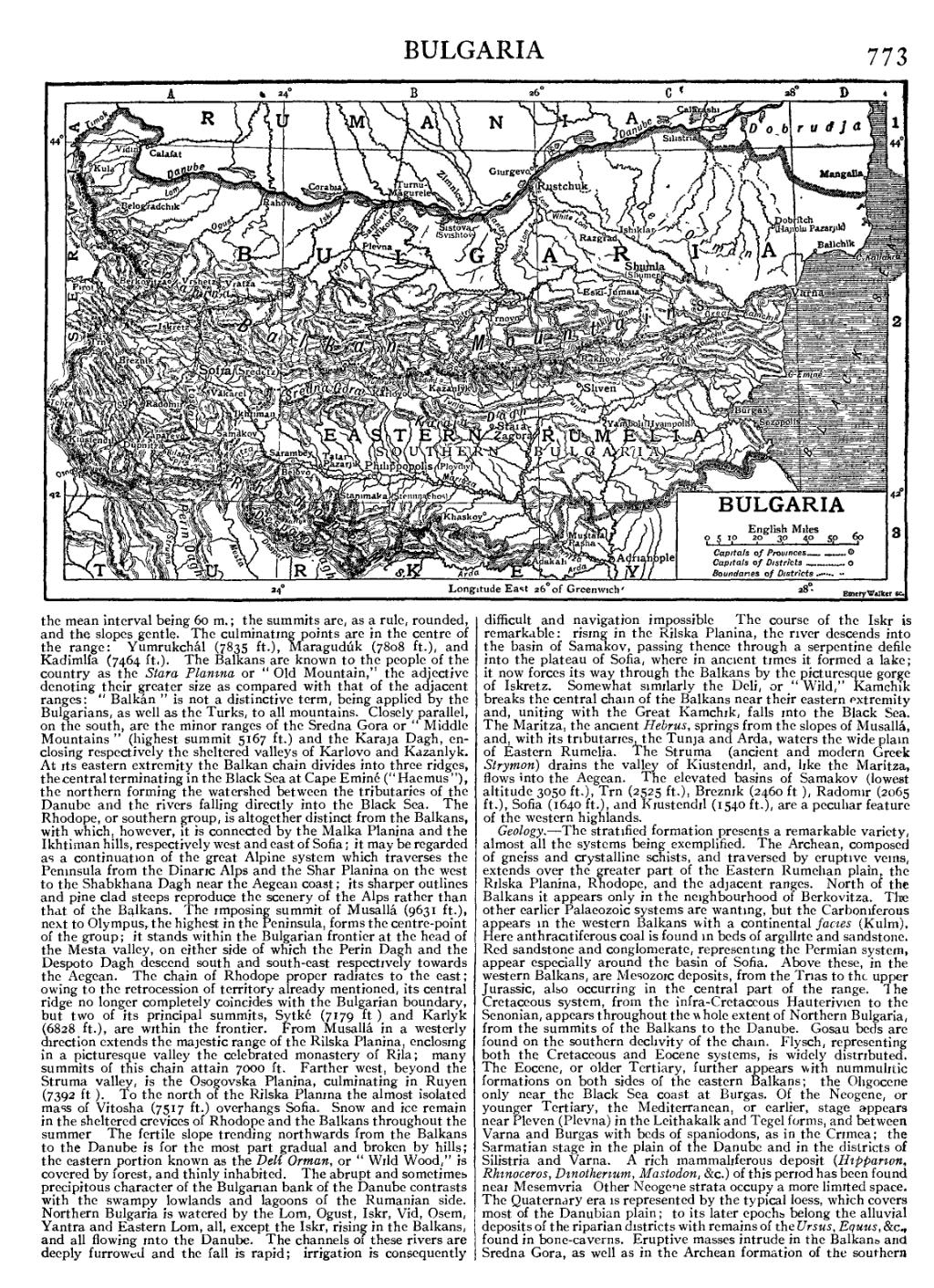

the mean interval being 60 m.; the summits are, as a rule, rounded, and the slopes gentle. The culminating points are in the centre of the range: Yumrukchál (7835 ft.), Maragudúk (7808 ft.), and Kadimlía (7464 ft.). The Balkans are known to the people of the country as the Stara Planina or “Old Mountain,” the adjective denoting their greater size as compared with that of the adjacent ranges: “Balkán” is not a distinctive term, being applied by the Bulgarians, as well as the Turks, to all mountains. Closely parallel, on the south, are the minor ranges of the Sredna Gora or “Middle Mountains” (highest summit 5167 ft.) and the Karaja Dagh, enclosing respectively the sheltered valleys of Karlovo and Kazanlyk. At its eastern extremity the Balkan chain divides into three ridges, the central terminating in the Black Sea at Cape Eminé (“Haemus”), the northern forming the watershed between the tributaries of the Danube and the rivers falling directly into the Black Sea. The Rhodope, or southern group, is altogether distinct from the Balkans, with which, however, it is connected by the Malka Planina and the Ikhtiman hills, respectively west and east of Sofia; it may be regarded as a continuation of the great Alpine system which traverses the Peninsula from the Dinaric Alps and the Shar Planina on the west to the Shabkhana Dagh near the Aegean coast; its sharper outlines and pine-clad steeps reproduce the scenery of the Alps rather than that of the Balkans. The imposing summit of Musallá (9631 ft.), next to Olympus, the highest in the Peninsula, forms the centre-point of the group; it stands within the Bulgarian frontier at the head of the Mesta valley, on either side of which the Perin Dagh and the Despoto Dagh descend south and south-east respectively towards the Aegean. The chain of Rhodope proper radiates to the east; owing to the retrocession of territory already mentioned, its central ridge no longer completely coincides with the Bulgarian boundary, but two of its principal summits, Sytké (7179 ft.) and Karlyk (6828 ft.), are within the frontier. From Musallá in a westerly direction extends the majestic range of the Rilska Planina, enclosing in a picturesque valley the celebrated monastery of Rila; many summits of this chain attain 7000 ft. Farther west, beyond the Struma valley, is the Osogovska Planina, culminating in Ruyen (7392 ft.). To the north of the Rilska Planina the almost isolated mass of Vitosha (7517 ft.) overhangs Sofia. Snow and ice remain in the sheltered crevices of Rhodope and the Balkans throughout the summer. The fertile slope trending northwards from the Balkans to the Danube is for the most part gradual and broken by hills; the eastern portion known as the Delí Orman, or “Wild Wood,” is covered by forest, and thinly inhabited. The abrupt and sometimes precipitous character of the Bulgarian bank of the Danube contrasts with the swampy lowlands and lagoons of the Rumanian side. Northern Bulgaria is watered by the Lom, Ogust, Iskr, Vid, Osem, Yantra and Eastern Lom, all, except the Iskr, rising in the Balkans, and all flowing into the Danube. The channels of these rivers are deeply furrowed and the fall is rapid; irrigation is consequently difficult and navigation impossible. The course of the Iskr is remarkable: rising in the Rilska Planina, the river descends into the basin of Samakov, passing thence through a serpentine defile into the plateau of Sofia, where in ancient times it formed a lake; it now forces its way through the Balkans by the picturesque gorge of Iskretz. Somewhat similarly the Deli, or “Wild,” Kamchik breaks the central chain of the Balkans near their eastern extremity and, uniting with the Great Kamchik, falls into the Black Sea. The Maritza, the ancient Hebrus, springs from the slopes of Musallá, and, with its tributaries, the Tunja and Arda, waters the wide plain of Eastern Rumelia. The Struma (ancient and modern Greek Strymon) drains the valley of Kiustendil, and, like the Maritza, flows into the Aegean. The elevated basins of Samakov (lowest altitude 3050 ft.), Trn (2525 ft.), Breznik (2460 ft.), Radomir (2065 ft.), Sofia (1640 ft.), and Kiustendil (1540 ft.), are a peculiar feature of the western highlands.

Geology.—The stratified formation presents a remarkable variety, almost all the systems being exemplified. The Archean, composed of gneiss and crystalline schists, and traversed by eruptive veins, extends over the greater part of the Eastern Rumelian plain, the Rilska Planina, Rhodope, and the adjacent ranges. North of the Balkans it appears only in the neighbourhood of Berkovitza. The other earlier Palaeozoic systems are wanting, but the Carboniferous appears in the western Balkans with a continental facies (Kulm). Here anthracitiferous coal is found in beds of argillite and sandstone. Red sandstone and conglomerate, representing the Permian system, appear especially around the basin of Sofia. Above these, in the western Balkans, are Mesozoic deposits, from the Trias to the upper Jurassic, also occurring in the central part of the range. The Cretaceous system, from the infra-Cretaceous Hauterivien to the Senonian, appears throughout the whole extent of Northern Bulgaria, from the summits of the Balkans to the Danube. Gosau beds are found on the southern declivity of the chain. Flysch, representing both the Cretaceous and Eocene systems, is widely distributed. The Eocene, or older Tertiary, further appears with nummulitic formations on both sides of the eastern Balkans; the Oligocene only near the Black Sea coast at Burgas. Of the Neogene, or younger Tertiary, the Mediterranean, or earlier, stage appears near Pleven (Plevna) in the Leithakalk and Tegel forms, and between Varna and Burgas with beds of spaniodons, as in the Crimea; the Sarmatian stage in the plain of the Danube and in the districts of Silistria and Varna. A rich mammaliferous deposit (Hipparion, Rhinoceros, Dinotherium, Mastodon, &c.) of this period has been found near Mesemvria. Other Neogene strata occupy a more limited space. The Quaternary era is represented by the typical loess, which covers most of the Danubian plain; to its later epochs belong the alluvial deposits of the riparian districts with remains of the Ursus, Equus, &c., found in bone-caverns. Eruptive masses intrude in the Balkans and Sredna Gora, as well as in the Archean formation of the southern