furnishes a proof that the influence and perhaps the commerce of the Greek colonies on the Black Sea spread far to the north through the countries of the Scythians and other barbarians. The fish dates from the 6th century B.C.

|

|

| Brit. Mus. | |

| Fig. 11.—Gold Ornaments from Camirus. | |

We may compare some of the gold ornaments from Camirus in Rhodes, which show an Ionian tendency, perhaps combined with Phoenician elements. On one of them (fig. 11) we see a centaur with human forelegs holding up a fawn, on the other the oriental goddess whom the Greeks identified with their Artemis, winged, and flanked by lions. This form was given to Artemis on the Corinthian chest of Cypselus, a work of art preserved at Olympia, and carefully described for us by Pausanias.

From Ionia the style of vase-painting which has been called by various names, but may best be termed the “orientalizing,” spread to Greece proper. Its main home here was in Corinth; and small Corinthian unguent-vases bearing figures of swans, lions, monsters and human beings, the intervals between which are filled by rosettes, are found wherever Corinthian trade penetrated, notably in the cemeteries of Sicily. For the larger Corinthian vases, which bore more elaborate scenes from mythology, we must again turn to the graves of the cities of Etruria. Here, besides the Ionian ware, of which mention has already been made, we find pottery of three Greek cities clearly defined, that of Corinth, that of Chalcis in Euboea, and that of Athens. Corinthian and Chalcidian ware is most readily distinguished by means of the alphabets used in the inscriptions which have distinctive forms easily to be identified. Whether in the style of the paintings coming from the various cities any distinct differences may be traced is a far more difficult question, into which we cannot now enter. The subjects are mostly from heroic legend, and are treated with great simplicity and directness. There is a manly vigour about them which distinguishes them at a glance from the laxer works of Ionian style. Fig. 12 shows a group from a Chalcidian vase, which represents the conflict over the dead body of Achilles. The corpse of the hero lies in the midst, the arrow in his heel. The Trojan Glaucus tries to draw away the body by means of a rope tied round the ankle, but in doing so is transfixed by the spear of Ajax, who charges under the protection of the goddess Athena. Paris on the Trojan side shoots an arrow at Ajax.

|

| Mon. d. Inst. i. 51. |

| Fig. 12.—Fight over the Body of Achilles. |

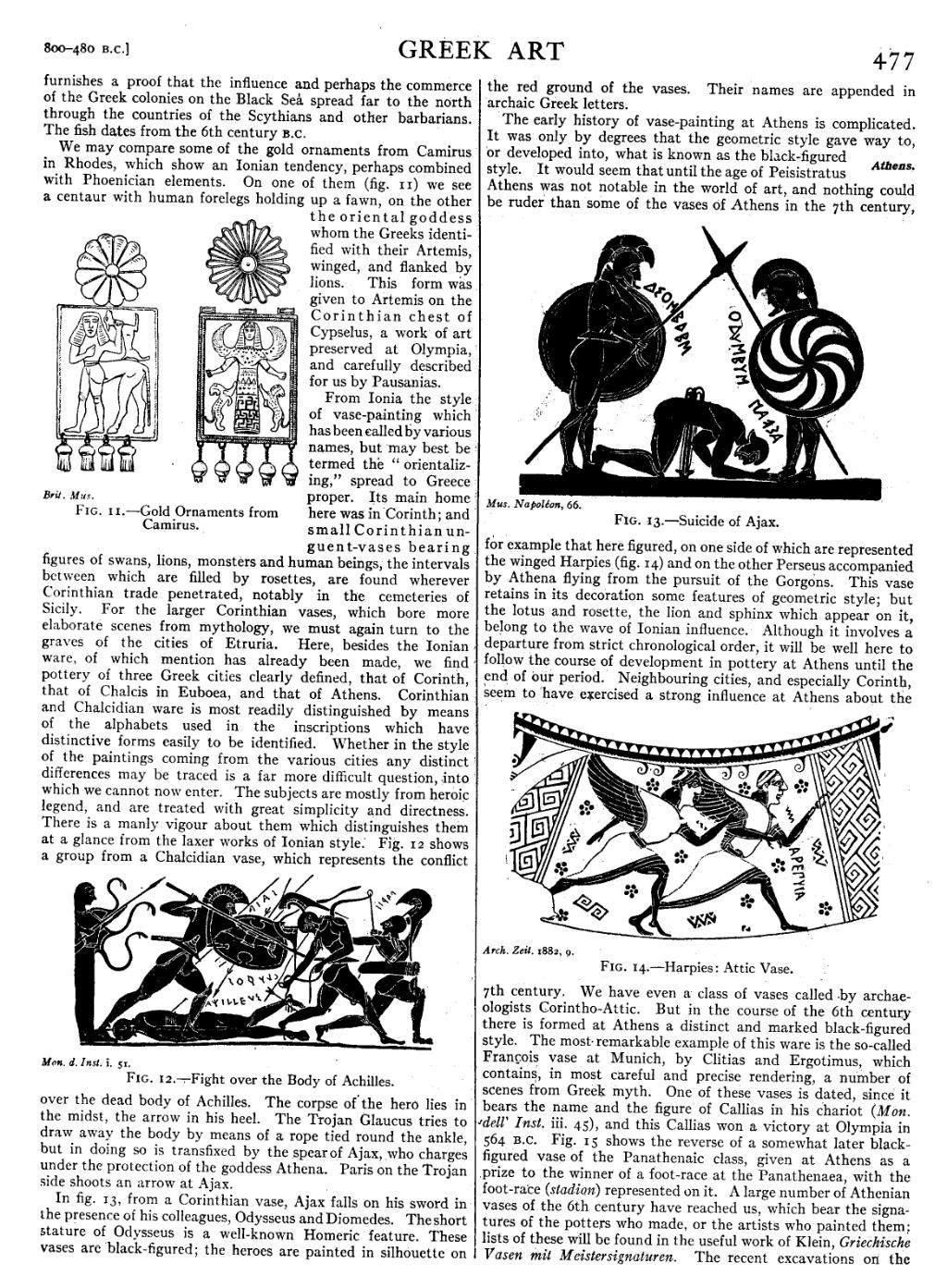

In fig. 13, from a Corinthian vase, Ajax falls on his sword in the presence of his colleagues, Odysseus and Diomedes. The short stature of Odysseus is a well-known Homeric feature. These vases are black-figured; the heroes are painted in silhouette on the red ground of the vases. Their names are appended in archaic Greek letters.

|

| Mus. Napoléon, 66. |

| Fig. 13.—Suicide of Ajax. |

|

| Arch. Zeit. 1882, 9. |

| Fig. 14.—Harpies: Attic Vase. |

The early history of vase-painting at Athens is complicated. It was only by degrees that the geometric style gave way to, or developed into, what is known as the black-figured style. It would seem that until the age of Peisistratus Athens was not notable in the world of art, and nothing could be ruder than some of the vases of Athens in the 7th century, Athens. for example that here figured, on one side of which are represented the winged Harpies (fig. 14) and on the other Perseus accompanied by Athena flying from the pursuit of the Gorgons. This vase retains in its decoration some features of geometric style; but the lotus and rosette, the lion and sphinx which appear on it, belong to the wave of Ionian influence. Although it involves a departure from strict chronological order, it will be well here to follow the course of development in pottery at Athens until the end of our period. Neighbouring cities, and especially Corinth, seem to have exercised a strong influence at Athens about the 7th century. We have even a class of vases called by archaeologists Corintho-Attic. But in the course of the 6th century there is formed at Athens a distinct and marked black-figured style. The most-remarkable example of this ware is the so-called François vase at Munich, by Clitias and Ergotimus, which contains, in most careful and precise rendering, a number of scenes from Greek myth. One of these vases is dated, since it bears the name and the figure of Callias in his chariot (Mon. dell’ Inst. iii. 45), and this Callias won a victory at Olympia in 564 B.C. Fig. 15 shows the reverse of a somewhat later black-figured vase of the Panathenaic class, given at Athens as a prize to the winner of a foot-race at the Panathenaea, with the foot-race (stadion) represented on it. A large number of Athenian vases of the 6th century have reached us, which bear the signatures of the potters who made, or the artists who painted them; lists of these will be found in the useful work of Klein, Griechische Vasen mit Meistersignaturen. The recent excavations on the