compelled a revision of the statutory tariff. Under this system

the ratio of the duties to the value of the dutiable goods was about

15.65%. The customs yield a revenue of about 42,000,000 yen.

In addition to the above there are eleven taxes, some in existence before the war of 1904–5, and some created for the purpose of carrying on the war or to meet the expenses of a post bellum programme.Other Taxes.

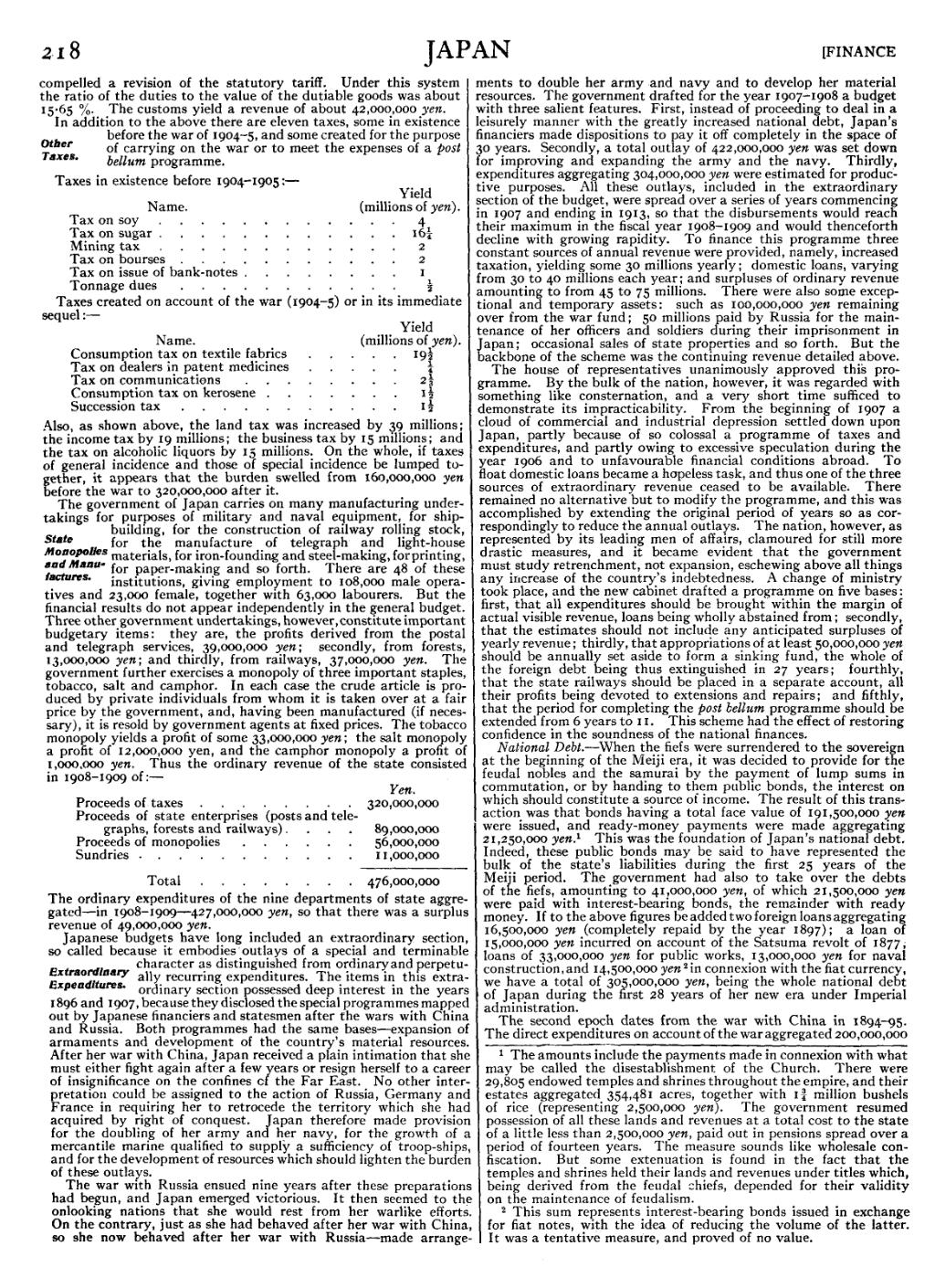

Taxes in existence before 1904–1905:—

| Name. | Yield (millions of yen). |

| Tax on soy | 4 |

| Tax on sugar | 1614 |

| Mining tax | 2 |

| Tax on bourses | 2 |

| Tax on issue of bank-notes | 1 |

| Tonnage dues | 12 |

Taxes created on account of the war (1904–5) or in its immediate sequel:—

| Name. | Yield (millions of yen). |

| Consumption tax on textile fabrics | 1912 |

| Tax on dealers in patent medicines | 14 |

| Tax on communications | 213 |

| Consumption tax on kerosene | 112 |

| Succession tax | 112 |

Also, as shown above, the land tax was increased by 39 millions; the income tax by 19 millions; the business tax by 15 millions; and the tax on alcoholic liquors by 15 millions. On the whole, if taxes of general incidence and those of special incidence be lumped together, it appears that the burden swelled from 160,000,000 yen before the war to 320,000,000 after it.

The government of Japan carries on many manufacturing undertakings for purposes of military and naval equipment, for ship-building, for the construction of railway rolling stock, for the manufacture of telegraph and light-house materials, for iron-founding and steel-making, for printing, State Monopolies and Manufactures. for paper-making and so forth. There are 48 of these institutions, giving employment to 108,000 male operatives and 23,000 female, together with 63,000 labourers. But the financial results do not appear independently in the general budget. Three other government undertakings, however, constitute important budgetary items: they are, the profits derived from the postal and telegraph services, 39,000,000 yen; secondly, from forests, 13,000,000 yen; and thirdly, from railways, 37,000,000 yen. The government further exercises a monopoly of three important staples, tobacco, salt and camphor. In each case the crude article is produced by private individuals from whom it is taken over at a fair price by the government, and, having been manufactured (if necessary), it is resold by government agents at fixed prices. The tobacco monopoly yields a profit of some 33,000,000 yen; the salt monopoly a profit of 12,000,000 yen, and the camphor monopoly a profit of 1,000,000 yen. Thus the ordinary revenue of the state consisted in 1908–1909 of:—

| Yen. | |

| Proceeds of taxes | 320,000,000 |

| Proceeds of state enterprises (posts and telegraphs, forests and railways) | 89,000,000 |

| Proceeds of monopolies | 56,000,000 |

| Sundries | 11,000,000 |

| Total | 476,000,000 |

The ordinary expenditures of the nine departments of state aggregated—in 1908–1909—427,000,000 yen, so that there was a surplus revenue of 49,000,000 yen.

Japanese budgets have long included an extraordinary section, so called because it embodies outlays of a special and terminable character as distinguished from ordinary and perpetually recurring expenditures. The items in this extraordinary section possessed deep interest in the years Extraordinary Expenditures. 1896 and 1907, because they disclosed the special programmes mapped out by Japanese financiers and statesmen after the wars with China and Russia. Both programmes had the same bases—expansion of armaments and development of the country’s material resources. After her war with China, Japan received a plain intimation that she must either fight again after a few years or resign herself to a career of insignificance on the confines of the Far East. No other interpretation could be assigned to the action of Russia, Germany and France in requiring her to retrocede the territory which she had acquired by right of conquest. Japan therefore made provision for the doubling of her army and her navy, for the growth of a mercantile marine qualified to supply a sufficiency of troop-ships, and for the development of resources which should lighten the burden of these outlays.

The war with Russia ensued nine years after these preparations had begun, and Japan emerged victorious. It then seemed to the onlooking nations that she would rest from her warlike efforts. On the contrary, just as she had behaved after her war with China, so she now behaved after her war with Russia—made arrangements to double her army and navy and to develop her material resources. The government drafted for the year 1907–1908 a budget with three salient features. First, instead of proceeding to deal in a leisurely manner with the greatly increased national debt, Japan’s financiers made dispositions to pay it off completely in the space of 30 years. Secondly, a total outlay of 422,000,000 yen was set down for improving and expanding the army and the navy. Thirdly, expenditures aggregating 304,000,000 yen were estimated for productive purposes. All these outlays, included in the extraordinary section of the budget, were spread over a series of years commencing in 1907 and ending in 1913, so that the disbursements would reach their maximum in the fiscal year 1908–1909 and would thenceforth decline with growing rapidity. To finance this programme three constant sources of annual revenue were provided, namely, increased taxation, yielding some 30 millions yearly; domestic loans, varying from 30 to 40 millions each year; and surpluses of ordinary revenue amounting to from 45 to 75 millions. There were also some exceptional and temporary assets: such as 100,000,000 yen remaining over from the war fund; 50 millions paid by Russia for the maintenance of her officers and soldiers during their imprisonment in Japan; occasional sales of state properties and so forth. But the backbone of the scheme was the continuing revenue detailed above.

The house of representatives unanimously approved this programme. By the bulk of the nation, however, it was regarded with something like consternation, and a very short time sufficed to demonstrate its impracticability. From the beginning of 1907 a cloud of commercial and industrial depression settled down upon Japan, partly because of so colossal a programme of taxes and expenditures, and partly owing to excessive speculation during the year 1906 and to unfavourable financial conditions abroad. To float domestic loans became a hopeless task, and thus one of the three sources of extraordinary revenue ceased to be available. There remained no alternative but to modify the programme, and this was accomplished by extending the original period of years so as correspondingly to reduce the annual outlays. The nation, however, as represented by its leading men of affairs, clamoured for still more drastic measures, and it became evident that the government must study retrenchment, not expansion, eschewing above all things any increase of the country’s indebtedness. A change of ministry took place, and the new cabinet drafted a programme on five bases: first, that all expenditures should be brought within the margin of actual visible revenue, loans being wholly abstained from; secondly, that the estimates should not include any anticipated surpluses of yearly revenue; thirdly, that appropriations of at least 50,000,000 yen should be annually set aside to form a sinking fund, the whole of the foreign debt being thus extinguished in 27 years; fourthly, that the state railways should be placed in a separate account, all their profits being devoted to extensions and repairs; and fifthly, that the period for completing the post bellum programme should be extended from 6 years to 11. This scheme had the effect of restoring confidence in the soundness of the national finances.

National Debt.—When the fiefs were surrendered to the sovereign at the beginning of the Meiji era, it was decided to provide for the feudal nobles and the samurai by the payment of lump sums in commutation, or by handing to them public bonds, the interest on which should constitute a source of income. The result of this transaction was that bonds having a total face value of 191,500,000 yen were issued, and ready-money payments were made aggregating 21,250,000 yen.[1] This was the foundation of Japan’s national debt. Indeed, these public bonds may be said to have represented the bulk of the state’s liabilities during the first 25 years of the Meiji period. The government had also to take over the debts of the fiefs, amounting to 41,000,000 yen, of which 21,500,000 yen were paid with interest-bearing bonds, the remainder with ready money. If to the above figures be added two foreign loans aggregating 16,500,000 yen (completely repaid by the year 1897); a loan of 15,000,000 yen incurred on account of the Satsuma revolt of 1877; loans of 33,000,000 yen for public works, 13,000,000 yen for naval construction, and 14,500,000 yen[2] in connexion with the fiat currency, we have a total of 305,000,000 yen, being the whole national debt of Japan during the first 28 years of her new era under Imperial administration.

The second epoch dates from the war with China in 1894–95. The direct expenditures on account of the war aggregated 200,000,000

- ↑ The amounts include the payments made in connexion with what may be called the disestablishment of the Church. There were 29,805 endowed temples and shrines throughout the empire, and their estates aggregated 354,481 acres, together with 134 million bushels of rice (representing 2,500,000 yen). The government resumed possession of all these lands and revenues at a total cost to the state of a little less than 2,500,000 yen, paid out in pensions spread over a period of fourteen years. The measure sounds like wholesale confiscation. But some extenuation is found in the fact that the temples and shrines held their lands and revenues under titles which, being derived from the feudal chiefs, depended for their validity on the maintenance of feudalism.

- ↑ This sum represents interest-bearing bonds issued in exchange for fiat notes, with the idea of reducing the volume of the latter. It was a tentative measure, and proved of no value.