mud and silt had been removed previous to its being raised; hence the greater depth at commencement of sinking.

When working in the hard boulder clay, for twenty-four hours with the full complement of twenty-seven men below in the air-chamber, and with four hydraulic spades going, a bucket was sent up every five minutes, or 288 buckets in the twenty-four hours, which was equal to a little over 5 cubic yards per man per twelve-hour shift. The total to 145 cubic yards for each foot in depth. Even this rate of progress was frequently exceeded under favourable circumstances, but was of course largely above the average daily work.

The different strata through which the caissons passed, were — water, deposited mud, stiff mud, silt, a layer of pebbles and stones, soft clay and boulder clay. In the last strata were found large rocks well rounded off, of granite, limestone, freestone and other kinds, many of which showed upon their flat faces, the distinct grooving or scoring due to glacier action. Amethysts and pebbles of all sorts, and large round boulders of conglomerate were also found, but no traces of fossils or of animal life, not even a live toad.

| All below High Water. | Level of | mud or silt | 27 ft. | 27½ ft. | 40 ft. | 52 ft. |

| " | clay and boulder clay | 48 ft. | 52½ ft. | 75 ft. | 62 ft. | |

| " | cutting edge at finish | 48 ft. | 52½ ft. | 75 ft. | 62 ft. | |

| Depth through hard ground | 23 ft. | 20½ ft. | 14 ft. | 23 ft. | ||

| Total excavation in cubic yards | 6372 | 6651 | 6827 | 6271 | ||

The excavation finished, the chamber was cleared of all material used during sinking, and preparations made for filling the whole space with concrete. The bottom ends of the air-shafts were closed by plates previously prepared, to which was attached a hinged door opening downwards. The large air locks were then removed from the tops of the shafts, and small tubes 18 in. in diameter fixed inside and carried up some distance to a platform, where the concrete mixer was stationed. A valve or small airlock was set on the top of the 18 in. tube. Outside the latter was of course ordinary atmospheric pressure. Similar arrangements were made for the other small shafts placed in the caissons from the beginning. Concrete was now deposited close to the lock, a signal was given, and the lower door in the air-chamber was hermetically sealed, the air let out of the shaft and the upper valve opened. Concrete was shovelled in till the pipe was nearly filled, the door then closed, and a signal given. Those below then opened a small valve to let compressed air into the shaft, the lower hinged door was opened and the mass of concrete fell on the floor and was taken up into barrows and carried all round the edge. There it was firmly rammed in and pounded with wooden rammers into every hole and corner, and thus gradually laid up the sloping face of the shoe. Against the ceiling also the concrete was carefully rammed, and thus by degrees the whole chamber built in, leaving only passages between the places where the concrete way passed down. These also were by degrees filled up and the last of the concrete had to be passed through the men's lock and down the air-shaft in buckets until this also had to be filled. The air pressure was of course kept on during all this time to keep the water from washing in and out. Finally, all the shafts were filled up, and cement grout was run into these until it stood up to the level of the water outside, the pressure being kept on these shafts for about thirty-six hours longer. The remaining space of the caisson above the air-chamber was now filled up with concrete to the low-water level at which the granite courses commenced.

The concrete in the air chamber was of the following proportions: Round the cutting edge and under the shoe, and for about 4 ft. all round within this space, 27 cubic feet of stone, 61⁄2 cubic feet of cement, and 61⁄2 cubic feet of sand. Inside this space and inside the caisson above the air-chamber, the proportions were 27 cubic feet of stone to 41⁄2 cubic feet of cement, and 41⁄2 cubic feet of sand. The grout used was pure cement and water.

Inchgarvie Caissons.

With regard to the Inchgarvie south caissons, the mode of working varied somewhat owing to the nature of the rock bottom. The preparations which had been made for the reception of these caissons, and the levelling by means of concrete piers and sandbags, has already been described. Previous to launching the two Inchgarvie caissons, a strong timber shoe was fixed in each of the two places which would come to lie immediately upon the two piers (Figs. 30 and 31), built up of concrete bags on the opposite side to where the caisson was likely to first touch the rock. The timber frame was brought down flush with the cutting edge, so as to give the caisson a solid base to rest on.

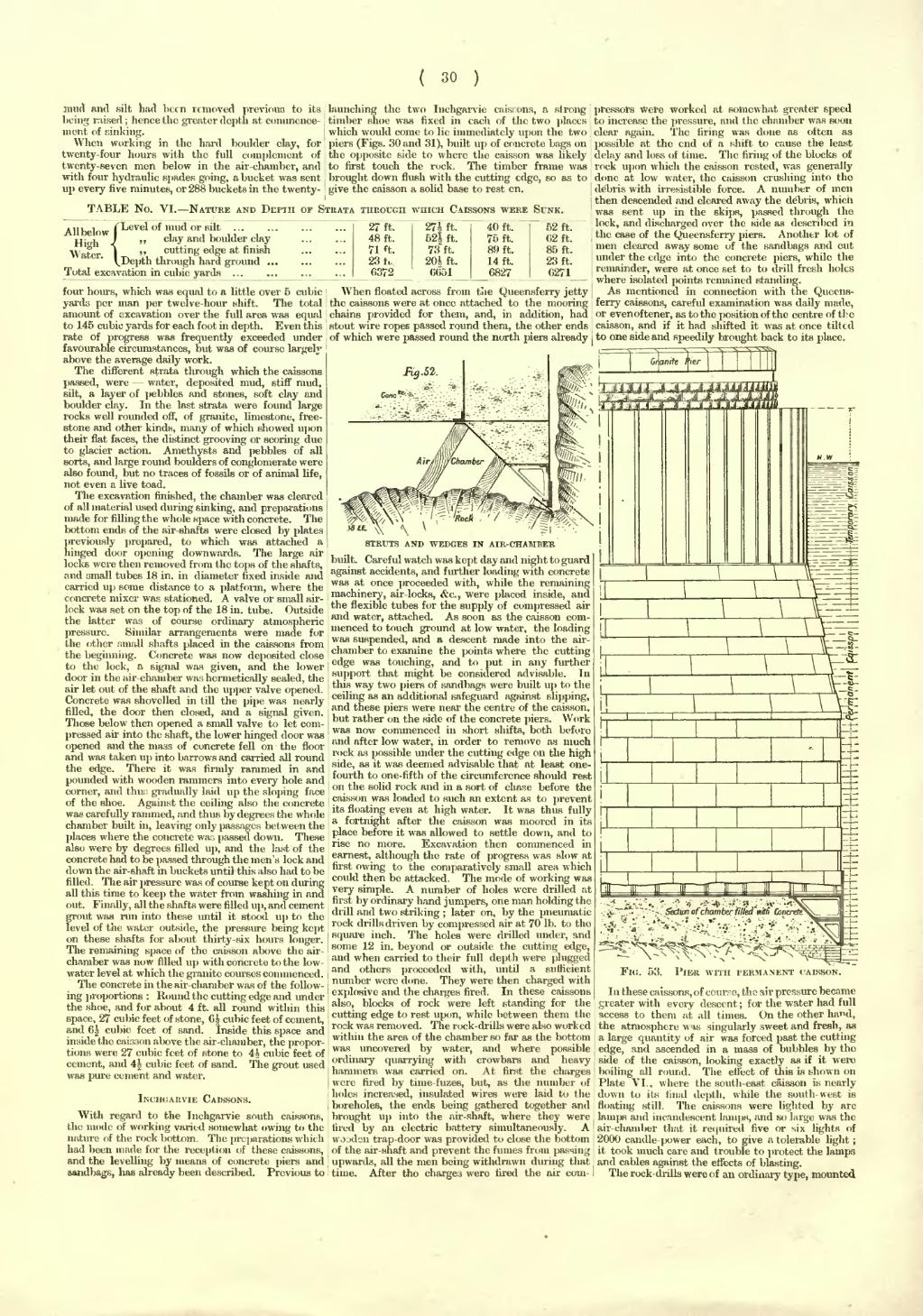

STRUTS AND WEDGES IN AIR CHAMBER

When floated across from the Queensferry jetty the caissons were at once attached to the mooring ferry chains provided for them, and, in addition, had stout wire ropes passed round them, the other ends of which were passed round the north piers already built. Careful watch was kept day and night to guard against accidents, and further loading with concrete was at once proceeded with, while the remaining machinery, air-locks, &c., were placed inside, and the flexible tubes for the supply of compressed air and water, attached. As soon as the caisson commenced to touch ground at low water, the loading was suspended and a descent made into the air-chamber to examine the points where the cutting edge was touching and to put in any further support that might be considered advisable. In this way two piers of sandbags were built up to the ceiling as an additional safeguard against slipping, and these piers were near the centre of the caisson, but rather on the side of the concrete piers. Work was now commenced in short shifts, both before and after low water, in order to remove as much rock as possible under the cutting edge on the high side, as it was deemed advisable that at least one-fourth to one-fifth of the circumference should rest on the solid rock and in a sort of chase before the caisson was loaded to such an extent as to prevent floating even at high water. It was thus fully a fortnight after the caisson was moored in its place before it was allowed to settle down, and to rise no more. Excavation then commenced in earnest, although the rate of progress was slow at first owing to the comparatively small area which could then be attacked. The mode of working was very simple. A number of holes were drilled at first by ordinary hand jumpers, one man holding the drill and two striking; later on by the pneumatic rock drills driven by compressed air at 70 lb. to the square inch. The holes were drilled under, and some 12 in. beyond or outside the cutting edge, and when carried to their full depth were plugged and others proceeded with, until a sufficient number were done. They were then charged with explosive and the charges fired. In these caissons also blocks of rock were left standing for the cutting edge to rest upon, while between them the rock was removed. The rock-drills were also worked within the area of the chamber so far as the bottom was uncovered by water, and where possible ordinary quarrying with crowbars and heavy hammers was carried on. At first the charges were fired by time-fuzes, but, as the number of holes increased, insulated wires were laid to the boreholes, the ends being gathered together and brought up into the air-shaft, where they were fired by an electric battery simultaneously. A wooden trap-door was provided to close the bottom of the air-shaft and prevent the fumes from passing upwards, all the men being withdrawn during that time. After the charges were fired the air compressors were worked at somewhat greater speed to increase the pressure, and the chamber was soon clear again. The firing was done as often as possible at the end of a shift to cause the least delay and loss of time. The firing of the blocks of rock upon which the caisson rested, was generally done at low water, the caisson crushing into the debris with irresistible force. A number of men then descended and cleared away the debris, which was sent up in the skips, passed through the lock, and discharged over the side as described in the case of the Queensferry piers. Another lot of men cleared away some of the sandbags and cut under the edge into the concrete piers, while the remainder, were at once set to to drill fresh holes where isolated points remained standing.

Fig. 53. Pier with permanent caisson.

As mentioned in connection with the Queensferry caisson, careful examination was daily made, or even oftener, as to the position of the centre of the caisson, and if it had shifted it was at once tilted to one side and speedily brought back to its place.

In these caissons, of course, the air pressure became greater with every descent; for the water had full access to them at all times. On the other hand, the atmosphere was singularly sweet and fresh, as a large quantity of air was forced past the cutting edge, and ascended in a mass of bubbles by the side of the caisson, looking exactly as if it were boiling all round. The effect of this is shown on Plate VI., where the south-east caisson is nearly down to its final depth, while the south-west is floating still. The caissons were lighted by arc lamps and incandescent lamps, and so large was the air-chamber that it required five or six lights of 2000 candle-power each, to give a tolerable light; it took much care and trouble to protect the lamps and cables against the effects of blasting.

The rock-drills were of an ordinary type, mounted