and the enfeebling infirmities and sufferings of those who survive. This is what took place in France during the long period of war that prevailed at the close of the eighteenth century and during the first empire.

Among the causes that operate upon the stature of individuals, considered separately, the first place is given to age. The growth of the infant, of the youth, and of the young man till maturity, is not proportional to their ages. It is more rapid in the earliest years, then keeps slackening till the time when the man, having reached maturity, ceases to grow. His stature then remains stationary till the approach of old age, after which it diminishes till the end of life. Some physiologists have tried to determine the law of the mean advance of growth. Buffon has given, month by month for the earliest infancy, afterward year by year, the growth of a young man. Dr. Lorain has represented graphically the variations in the growth in stature and weight of two children; during the first year for one of them, Jean Lorain (Fig. 3), and during the first two years for Juliette R (Fig-4). In these graphics the lower curve corresponds with the stature, and the upper one with the weight; and they enable us to observe the arrest of growth that may have been caused by the sufferings of the child. In Jean Lorain's curve we see the pause that took place when the subject was vaccinated, an arrest which continued, accompanied by a considerable loss of weight, during a period of pneumonia. The occasion of the appearance of the first two teeth also caused an arrest of growth. We can see in like manner on Juliette R's curve pauses of growth in both lines, corresponding with indisposition.

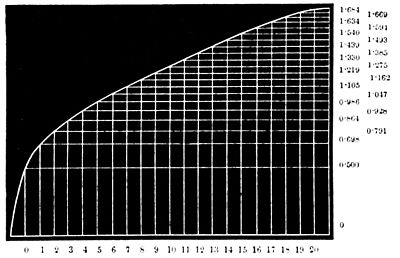

Quetelet has represented the mean increase of stature according to age by a curve. The curve has a clearly-defined parabolical form

Fig. 5.—Parabolical curve, representing, by millimetres, the increase in height according to age. (From Quetelet's "Anthropometry.")

(Fig. 5). It supposes the child to be fifty centimetres (or twenty inches) at birth. While this curve represents the mean, there are in reality very characteristic differences in the course of growth of children. Independently of the influence of sickness, accidents, ex-