Popular Science Monthly/Volume 31/July 1887/Variations in Human Stature

| VARIATIONS IN HUMAN STATURE. |

By M. GUYOT DAUBÉS.

THE study of human stature involves several questions of more important interest than that of mere theory or curiosity. It may aid us in learning whether the human race is really degenerating, as some persons assert, by determining whether our ancestors in heroic and prehistoric times had the superior physical prowess that is often ascribed to them. It should teach us whether there are races of dwarfs and of giants, and what are the distances separating the races that most nearly approach those descriptions. We learn from it the exact facts respecting the differences in stature among the people of a single nation, our own, for instance, to which military men attach high value. Other fields of inquiry, of a practical bearing, regard the causes that influence the stature of populations and races in general, and the growth of individuals, from infancy up; and the influence of stature upon the force, agility, endurance, and physical development of individuals. An opinion was current, in the last century, that our ancestors, at some time in the past, were the equals or superiors in size to the largest men now to be found. M. Henrion presented to the Académie des Inscriptions, in 1718, a memoir on the variations in the size of man from the beginning of the world till the Christian era, in which Adam was given one hundred and twenty-three feet nine inches, and Eve one hundred and eighteen feet nine and three fourths inches. But after the first pair, the human race, in his imagination, suffered a regular decrease, so that Noah was only one hundred feet high, while Abraham shrank down to twenty-eight feet, Moses to thirteen feet, the mighty Hercules to ten feet eight and a half inches, and Alexander the Great to a bare six feet and a half. The communication, it is said, was received with enthusiasm, and was regarded, at the time, as a "wonderful discovery" and a "sublime vision"

The complaint about the degeneracy of the human race is not new, but dates as far back as the time of Homer, at least; for the men of his day were not like the heroes of whom he sang. It is not confirmed, but is contradicted by all the tangible facts, and these are not a few. Human remains that are exhumed, after having reposed in the grave for many centuries, as in the Catacombs of Paris, have nothing gigantic about them. The armor, the cuirasses, and the casques of the warriors of the middle ages, can be worn by modern soldiers; and many of the knights' suits would be too small for the cuirassiers of the European armies; yet they were worn by the selected men, who were better fed, stronger, and more robust than the rest of the population. The bones of the ancient Gauls, which are uncovered in the excavations of tumuli, while they are of large dimensions, are comparable with those of the existing populations of many places in France.

The Egyptian mummies are the remains of persons of small or medium stature, as are also the Peruvian and Mexican mummies, and the mummies and bones found in the ancient monuments of India and Persia. And even the most ancient relics we possess of individuals of the human species, the bones of men who lived in the Tertiary period, an epoch the remote antiquity of which goes back for hundreds of centuries, do not show any important differences in the sizes of the primitive and of the modern man.

Considerable differences will be found to exist, when we compare the statures of the various races of mankind; and it is the exaggeration of this fact that has given rise to the legends of dwarf and giant peoples. Individuals of the supposed dwarf races would appear quite large if compared with real dwarfs. A dwarf much over three feet high begins to lose interest as a dwarf; if he reaches four feet and more, he ceases to be a dwarf, and becomes a "little man." Now, the well-shaped adults of the smaller human races always, with very few exceptions, exceed four feet in height. These races are not, therefore, dwarfs, but simply small races. It is, nevertheless, interesting to study them, and compare them with the larger races. So, in these latter races, men much exceeding seven feet are exceptional, and merit the name of giants. Still, the average of stature in these larger races is much more considerable than in the smaller races; and a man of the average size, among them, would be a giant compared with an average specimen of the smaller races.

Among the smaller races are the Esquimaux, averaging five feet, two inches; the Lapps—men, five feet one inch, women, four feet seven inches; the Akkas seen by Schweinfurth in Africa; the Negritos of the Philippine and Andaman Islands, and Malacca; the dwarf race of Madagascar; and the Bushmen, whose height ranges from four feet five inches to four feet six and three fourths inches.

Among the large races may be mentioned the Norwegians, the Canadians, the North American Indians, the Caffres, the Patagonians, and the Polynesians, the average height of the last two of which is estimated at about six feet. The difference in the mean height of the various human races is, therefore, that between four feet five inches and six feet, or one foot seven inches. The mean between these two numbers is about five feet three inches; and this standard is generally agreed upon by anthropologists as a division line in the approximative classification of the races according to their height. Those are called medium races which average from five and one fourth to five and a half feet; small races, which are less than five and one fourth feet; and large races, which are more than five and a half feet in height.

From time to time there are found in different populations individuals whose stature departs much from the mean, either in excess—"giants"—or in deficiency—"dwarfs"; and teratology has failed to find adequate explanations of the causes of such variations.

If we may believe the ancient authors, a large number of giants and giantesses attained extraordinary stature, even for persons of that class. Pliny mentions the giant Gabbara, who was nine feet nine inches tall, and two other giants, Poison and Secundilla, who were half a foot taller; Garopius tells of a young giantess who was ten feet high; and Lecat, of a Scotch giant, eleven and a half feet in height. But we may take it for granted that these figures are greatly

The mean between these two extremes of stature is about five feet five and a half inches, and the difference between them is six feet one and a half inch. The mean height is nearly the same with the average stature of Frenchmen. We give an illustration embodying a comparative representation of these extremes, with three intervals between

Fig. 2.—Variations in Human Stature. The giant Winckelmeier. 2·60 metres. A cuirassier, 1·80 m. A man of the average size, 1·66 m. A little soldier, 1·54 in. The dwarf Borulawsky, 0·75 m. A new-born babe, 0·50 m.

that of Winckelmeier from a recent photograph. Beside them are placed a new-born infant of twenty inches, an infantry soldier of minimum stature (five feet one inch), a man of average size (five feet five inches), and a cuirassier of six feet. The illustration comprises all the important variations in human stature.

The conditions that affect the stature of populations and races of men may all be described under one general head that of nutrition. The size of a population, a race, or a group of individuals living for several generations in the same conditions of environment and resources, is proportionate to its nutrition. Coming to particulars, we find that this nutrition depends, first, on the aptitude for assimilation, which is a question of climate; and, second, upon the facility with which the people can obtain a quantity of food in proportion to their power of assimilation.

It was long believed that climate alone had a great influence on stature; and, in fact, if we regard the white or light-colored races, we remark that the stature is less in climates of extreme temperatures than in temperate latitudes. In the extremely cold Arctic regions, the Lapps, Esquimaux, and Greenlanders are very small; but coming down into more temperate regions and more fertile countries, we find much larger races, like the Norsemen, Russians, Anglo-Saxons, and North-Germans in Europe, and the Canadians and Indians in America. Farther south, and as the temperature becomes hotter, the stature diminishes; a fact which may be verified among the Italians and Spaniards, and which is observed in most of the great regions of the globe.

These variations are not the effect of climate, but are directly dependent, as we have already said, on nutrition. In very cold climates, assimilation is excessive, for the organism needs a large quantity of food to sustain it against the outer temperature. If, in consequence of the rigor of the climate and the limited resources of the country in game and fish, waste is a little superior, or quite equal, to assimilation, the population subject to such conditions must continue small. This is the case with the Laplanders and the Esquimaux of the Arctic islands and the east coast of Greenland. But when game and fish are abundant, the stature of the tribe rises; as takes place with the Esquimaux, whose average height increases as their habitat draws nearer to their southern limit. There the Esquimaux cease to be dwarfs and reach the average height of five and a half feet, or greater than that of the French population. The climate is still rigorous in Canada, and organic assimilation very active, but the country is fertile and food abundant. There the native Indians and the colonists of European origin attain great size and vigor. The Norsemen and the Russians in Europe are in analogous conditions. On what a Russian mujik eats in a day a Spanish peasant could subsist for a week. It is to the influence of a keen winter cold and the assimilative power that results from it that the Anglo-Saxon and Germanic races, and the northern and eastern French, owe their size and strength. As the climate grows warm, and the summer heat becomes excessive, nutrition becomes less active and the mean stature of the population decreases: Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece are examples of this. The influence of climate upon stature is therefore a question of faculty of assimilation and of the quantity of available food. For this last reason, the fertility of the soil has a considerable influence upon the size of the population. A well-cultivated country, furnishing abundance of food and cattle, permits its population to acquire a much greater size, strength, and robustness than would be possible to a population living on infertile lands insufficiently supporting its inhabitants. By the same influences members of families in easy circumstances, and standing in the position of old proprietors, are usually heartier than poorer families; the inhabitants of towns than those of the surrounding rural districts.

| Fig. 3.—Curve of the increase of height and weight of a little boy (Jean Lorain) during his first year. (After Dr. Lorain.) | Fig. 4.—Curve of the increase in height and weight of a little girl (Juliette R.——). during her first two tears. (After Dr. Lorain.) |

(In each of these figures the weight, is marked in kilogrammes outside of the diagram, and the rate of growth in height is indicated in fractions of a metre within the first column.)

Famines and frequent or prolonged dearths have the effect of reducing the size of the peoples who are exposed to them. Wars induce the same result, and this not only by the operation of the material disasters and miseries which they occasion, but also through the loss of a large number of the most vigorous and robust men of the nation, and the enfeebling infirmities and sufferings of those who survive. This is what took place in France during the long period of war that prevailed at the close of the eighteenth century and during the first empire.

Among the causes that operate upon the stature of individuals, considered separately, the first place is given to age. The growth of the infant, of the youth, and of the young man till maturity, is not proportional to their ages. It is more rapid in the earliest years, then keeps slackening till the time when the man, having reached maturity, ceases to grow. His stature then remains stationary till the approach of old age, after which it diminishes till the end of life. Some physiologists have tried to determine the law of the mean advance of growth. Buffon has given, month by month for the earliest infancy, afterward year by year, the growth of a young man. Dr. Lorain has represented graphically the variations in the growth in stature and weight of two children; during the first year for one of them, Jean Lorain (Fig. 3), and during the first two years for Juliette R (Fig-4). In these graphics the lower curve corresponds with the stature, and the upper one with the weight; and they enable us to observe the arrest of growth that may have been caused by the sufferings of the child. In Jean Lorain's curve we see the pause that took place when the subject was vaccinated, an arrest which continued, accompanied by a considerable loss of weight, during a period of pneumonia. The occasion of the appearance of the first two teeth also caused an arrest of growth. We can see in like manner on Juliette R's curve pauses of growth in both lines, corresponding with indisposition.

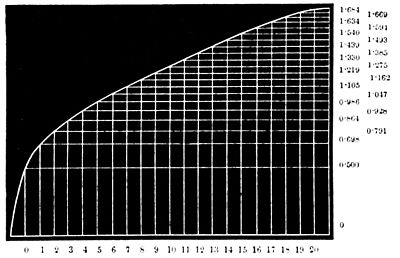

Quetelet has represented the mean increase of stature according to age by a curve. The curve has a clearly-defined parabolical form

Fig. 5.—Parabolical curve, representing, by millimetres, the increase in height according to age. (From Quetelet's "Anthropometry.")

(Fig. 5). It supposes the child to be fifty centimetres (or twenty inches) at birth. While this curve represents the mean, there are in reality very characteristic differences in the course of growth of children. Independently of the influence of sickness, accidents, excessive mental labors, anxieties about examinations, all causes that have an influence on growth, there are children whose growth is more accentuated than the mean at some period of their existence; and others, tardy ones, who grow till twenty-five or thirty years old, or even longer. With very many youth, growth does not stop at twenty-one years.

The rate of growth of children varies according to sex. Thus, at the age of eleven and twelve years, boys are larger and heavier than girls; but from that age on the evolution of the girls is more rapid, and they soon overtake the boys and pass them, till the age of fifteen years is reached, when the boys regain the ascendency, while the girls remain nearly stationary. A curious relation has been discovered between the growth of children in stature and in weight. M. Malling-Hansen, Director of the Deaf and Dumb Institution at Copenhagen, has for three years weighed and measured his pupils daily; and he has observed that their growth does not take place regularly and progressively, but by stages separated by intervals of rest. Weight also increases by periods after intervals of equilibrium. While the weight is increasing, the stature remains nearly stationary, and vice versa. The maximum of increase of stature corresponds with a minimum period of augmentation of weight. The vital forces appear not to work on both sides at once. These variations are subject to the influence of the seasons. During autumn and early winter, according to M. Malling-Hansen, the child accumulates weight, while his stature increases slowly; but during spring, stature receives a veritable push, while weight increases but little. Some local habits have an influence on the stature. Stendhal remarked that many Roman girls had deformed vertebral columns, or were a little humpbacked, and found that it was the result of a popular belief prevailing in Rome that parents could promote the growth of their children by punching them in the back! A popular custom in some of the towns of Switzerland also affects the development of the children. Mothers are accustomed to give them brandied lumps of sugar to keep them from crying. It has been learned from experiments on animals that alcohol tends to stunt the growth of the young. The habit of some women of the lower classes of drinking brandy during pregnancy in order to give their children fair complexions must likewise have a bad influence on the development of the children. On the other hand, growth is favored by strong food, rich in nitrogen and phosphates, by good hygiene, by play and gymnastic exercises, by plenty of air, and by all the causes that contribute to make children strong and vigorous.

One of the less recognized agencies affecting stature is fatigue, under the influence of which the height diminishes. A soldier, for instance, is perceptibly taller before than after a forced march; when the body is fatigued it gives way, the cartilages lose their elasticity and become thinner, and the fatty and fibrous cushions, which give spring to the organs of locomotion, become less supple and more attenuated, all of which contribute to the diminution of height. Carrying burdens on the head or shoulders leads to the same results. If to an excessive fatigue is added privation of sleep, organic reparation can not take place, and the causes which contribute to the diminution of stature accumulate and effect in the total a decrease which is relatively considerable. This fact is known to the tricksters who practice upon young men liable to military service so as to secure exemptions for them. If the men are only a few centimetres over the minimum standard of the service, these practitioners put them through a variety of fatiguing exercises, with carrying of burdens and privations, etc., till they succeed in reducing them below the minimum and causing them to be rejected on examination. The same influence of fatigue is also felt in ordinary life. The simple standing position, walking, and riding, all contribute to a reduction of the height. We are all taller in the morning than in the evening. Professor Martel made a communication on this subject to the German Surgical Congress held in Berlin in 1881, and presented a number of measurements, from which he concluded that men's statures varied perceptibly according to the hour of the day. The variation differs according to occupations, being less in the case of those which are sedentary.

The height of the adult continues stationary during mature age, but begins to diminish at about fifty-five or sixty years. The decrease is independent of the curvature of the vertebral column, and is exhibited upon robust men who still hold themselves up straight. It depends upon several causes, among which are a modification of the neck of the femur, flattening of the fatty cushions, with gradual ossification and decrease in thickness of the cartilages of the joints, particularly of those of the vertebral column.

Physical aptitudes are various according to stature; and we are able to draw important conclusions, particularly with reference to fitness for military service, from the determination of them. The bodily vivacity of small men is very much greater than that of large men. The man of small stature is nearly always quicker and more alert than a man who is tall and stout in proportion. This should be evident, for such a man has less weight to displace when he is moving, jumping or climbing; while it has been proved, by many experiments on animals, that the strength does not increase in proportion to the weight. Two horses weighing together three quarters of a ton can perform much more work, particularly if it be work involving rapidity, than a single horse having the same weight. A similar difference exists in the power of one large and stout man and two small men. The ratio of muscular energy to the pound of living weight is much greater with small or middling-sized men than with very large ones. The length of the limbs of the latter necessarily occasions an amplitude in his motions that makes execution slower. Length of limbs also contributes to a waste of strength. We can compare the arm, for instance, with a lever, the fulcrum of which is at the shoulder-joint, the point of action at the hand, and the power in the muscles. It is evident that the larger the arm of this lever is, the more energetic will the muscular effort have to be. The large man's power of endurance is less than that of the middling-sized man, because not only of the personal weight that has to be carried, but also on account of the difference in the proportional development of the respiratory system. The power of endurance may be estimated in a man at rest by taking the proportion between the height and the circumference of the breast at the height of the mammary processes. The larger the proportion of the latter element, the greater will be the power to resist fatigue. The French marine formerly accepted only those men whose breast-measurement was at least half their height. The same degree of development is required in Switzerland, and the acceptance of young men who can not display it is adjourned from year to year. Thus, looking at military aptitudes, it is middling-sized or small men that offer the greatest energy, power to resist fatigue, and activity in battle; and of this kind is the popular type of the French soldier—the petit chasseur, or the soldier of the line.—Translated for the Popular Science Monthly from La Nature.