Popular Science Monthly/Volume 41/August 1892/The Diamond Industry at Kimberley

| THE DIAMOND INDUSTRY AT KIMBERLEY.[1] |

By LORD RANDOLPH CHURCHILL.

Kimberley and its Diamond Mine. (From Reclus's The Earth and its Inhabitants.)

carats of diamonds, realizing by sale over £3,500,000, produced by washing some 2,700,000 loads of blue ground. Each load represents three quarters of a ton, and costs in extracting about 8s. 10d. per load, realizing a profit of 20s. to 30s. per carat sold. The annual amount of money paid away in interest and dividends exceeds £1,300,000. The dividends might have been much larger, but the

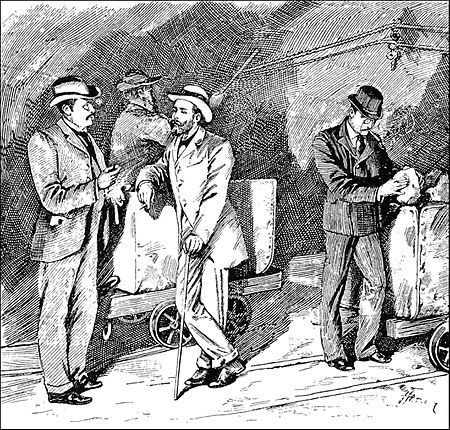

Classified for Shipment at Kimberley.

policy of the present board of directors appears to be to restrict the production of diamonds to the quantity the world can easily absorb, to maintain the price of the diamonds at a fair level from 28s. to 32s. per carat, and, in order the better to carry out this policy, to accumulate a very large cash reserve. I believe that the reserve already accumulated amounts to nearly £1,000,000, and that this amount is to be doubled in the course of the next year or two, when the board will feel that they have occupied for their shareholders a position unassailable by any of the changes and chances of commerce. In the working of the mine there are employed about 1,300 Europeans and 5,700 natives. The wages paid range high, and figures concerning them may interest the English artisan. Mechanics and engine-drivers receive from £6 to £7 per week, miners from £5 to £6, guards and tally-men from £4 to £5; natives in the underground works are paid from 4s. to 5s. per day. In the work on the "floors" which is all surface work, overseers receive from £3 12s. to £4 2s., machine-men and assorters from £5 to £6, and ordinary native laborers from 17s. 6d. to 21s. per week. In addition, every employé on the "floors" has a percentage on the value of diamonds found by himself, the white employés receiving 1s. 6d., and the natives 3d., per carat. Nearly double these amounts are paid for stones found in the mines.

Mr. Gardner Williams, the eminent mining engineer who occupies the important post of general manager to the De Beers Company, was kind enough to accompany me all over the mines, and to explain in detail the method of operation. The De Beers and the Kimberley mines are probably the two biggest holes which greedy man has ever dug into the earth, the area of the former at the surface being thirteen acres, with a depth of 450 feet, the area and depth of the latter being even greater. These mines are no

| Mr. Gardner Williams. | Lord Randolph Churchill. | Captain Williams. |

In the Rock Shaft of the De Beers Diamond Mine at a Depth of Nine Hundred Feet.

longer worked from the surface, but from shafts sunk at some distance from the original holes, and penetrating to the blue ground by transverse drivings at depths varying from 500 to 1,200 feet. The blue ground, when extracted, is carried in small iron trucks to the "floors." "These are made by removing the bush and grass from a fairly level piece of ground; the land is then rolled and made as hard and as smooth as possible. These 'floors' are about 600 acres in extent. They are covered to the depth of about a foot with the blue ground, which for a time remains on them without much manipulation. The heat of the sun and moisture soon have a wonderful effect upon it. Large pieces which were as hard as ordinary sandstone when taken from the mine, soon commence to crumble. At this stage of the work, the winning of the diamonds assumes more the nature of farming than of mining; the ground is continually harrowed to assist pulverization by exposing the larger pieces to the action of the sun and rain. The blue ground from Kimberley mine becomes quite well pulverized in three months, while that from De Beers requires double that time. The longer the ground remains exposed, the better it is for washing."[2] The process of exposure being completed, the blue ground is then carried to very large, elaborate, and costly washing machines, in which, by means of the action of running water, the diamonds are separated from the ordinary earth. It may be mentioned that in this process one hundred loads of blue ground are concentrated into one load of diamondiferous stuff. Another machine, the "pulsator," then separates this latter stuff, which appears to be a mass of blue and dark pebbles of all shapes, into four different sizes, which then pass on to the assorters. "The assorting is done on tables, first while wet by white men, and then dry by natives."[3] The assorters work with a kind of trowel, and their accuracy in detecting and separating the diamond from the eight different kinds of mineral formations which reach them is almost unerring. "The diamond occurs in all shades of color from deep yellow to a blue white, from deep brown to light brown, and in a great variety of colors, green, blue, pink, brown, yellow, orange, pure white, and opaque."[4] The most valuable are the pure white and the deep orange. "The stones vary in size from that of a pin's head upward; the largest diamond yet found weighed 428½ carats. It was cut and exhibited at the Paris Exhibition, and after cutting weighed 228½ carats.

"After assorting, the diamonds are sent daily to the general office under an armed escort and delivered to the valuators in charge of the diamond department. The first operation is to clean the diamonds of any extraneous matter by boiling them in a mixture of nitric and sulphuric acids. When cleaned they are carefully assorted again in respect of size, color, and purity."[5] The room in the De Beers office where they are then displayed offers a most striking sight. It is lighted by large windows, underneath which runs a broad counter covered with white sheets of paper, on which are laid out innumerable glistening heaps of precious stones of indescribable variety. In this room are concentrated some 60,000 carats, the daily production of the Consolidated Mine being about 5,500 carats. "When the diamonds have been valued they are sold in parcels to local buyers, who represent the leading diamond merchants of Europe. The size of a parcel varies from a few thousand to tens of thousands of carats; in one instance, two years ago, nearly a quarter of a million of carats were sold in one lot to one buyer."[6]

The company sustain a considerable loss annually, estimated now at from 10 to 15 per cent, by diamonds being stolen from the mines. To check this loss, extraordinary precautions have been resorted to. The natives are engaged for a period of three months, during which time they are confined in a compound surrounded by a high wall. On returning from their day's work, they have to strip off all their clothes, which they hang on pegs in a shed. Stark naked, they then proceed to the searching-room, where their mouths, their hair, their toes, their armpits, and every

In the Eight-Hundred-Feet Level of the De Beers Diamond Mine.

portion of their bodies are subjected to an elaborate examination. White men would never submit to such a process, but the native sustains the indignity with cheerful equanimity, considering only the high wages which he earns. After passing through the searching-room, they pass, still in a state of nudity, to their apartments in the compound, where they find blankets in which to wrap themselves for the night. During the evening the clothes which they have left behind them are carefully and minutely searched, and are restored to their owners in the morning. The precautions which are taken a few days before the natives leave the compound, their engagement being terminated, to recover diamonds which they may have swallowed, are more easily imagined than described. In addition to these arrangements, a law of exceptional rigor punishes illicit diamond buying, known in the slang of South Africa as I. D. B.ism. Under this statute, the ordinary presumption of law in favor of the accused disappears, and an accused person has to prove his innocence in the clearest manner, instead of the accuser having to prove his guilt. Sentences are constantly passed on persons convicted of this offense ranging from five to fifteen years. It must be admitted that this tremendous law is in thorough conformity with South African sentiment, which elevates I. D. B.ism almost to the level, if not above the level, of actual homicide. If a man walking in the streets or in the precincts of Kimberley were to find a diamond and were not immediately to take it to the registrar, restore it to him, and to have the fact of its restoration registered, he would be liable to a punishment of fifteen years' penal servitude. In order to prevent illicit traffic, the quantities of diamonds produced by the mines are reported to the detective department both

Sorting Gravel for Diamonds at Kimberley.

by the producers and the exporters. All diamonds, except those which pass through illicit channels, are sent to England by registered post, the weekly shipments averaging from 40,000 to 50,000 carats. The greatest outlet for stolen diamonds is through the Transvaal to Natal, where they are shipped by respectable merchants, who turn a deaf ear to any information from the diamond fields to the effect that they are aiding the sale of stolen property.[7] The most ingenious ruses are resorted to by the illicit dealers for conveying the stolen diamonds out of Kimberley. They are considerably assisted by the fact that the boundaries of the Transvaal and of the Free State approach within a few miles of Kimberley, and once across the border they are comparatively safe. Recently, so I was informed, a notorious diamond thief was seen leaving Kimberley on horseback for the Transvaal. Convinced of his iniquitous designs, he was seized by the police on the border and thoroughly searched. Nothing was found on him, and he was perforce allowed to proceed. No sooner was he well across the border, than he, under the eyes of the detective, deliberately shot and cut open his horse, extracting from its intestines a large parcel of diamonds, which, previous to the journey, had been administered to the unfortunate animal in the form of a ball.

The De Beers directors manage their immense concern with great liberality. A model village, called Kenilworth, within the precincts of the mines, affords most comfortable and healthy accommodation for several of the European employés. Gardens are attached to cottages, and the planting of eucalyptus, cypress, pine, and oak, as well as a variety of fruit trees, has been carried to a considerable extent. A very excellent club-house has also been built, which includes, besides the mess-room and kitchen, a reading-room, where many of the monthly papers and magazines are kept, together with six hundred volumes from the Kimberley Public Library. There is also a billiard-room, with two good tables given by two of the directors. A large recreation-ground is in the course of construction. Within the compound where the native laborers are confined is a store where they can procure cheaply all the necessaries of life. Wood and water are supplied free of charge, and a large swimming-bath is also provided, but I did not learn if the natives made much use of it. All sick natives are taken care of in a hospital connected with the compound, where medical attendance, nurses, and food are supplied gratuitously by the company. I should not omit to mention that the entire mine, above and under ground, is lighted by electricity. There are ten circuits of electric lamps for De Beers and Kimberley mines. They consist of fifty-two arc lamps of 1,000 candlepower each, and 691 glow lamps of sixteen and sixty -four candlepower each, or a total illuminating power of 63,696 candles. There are, moreover, thirty telephones connecting the different centers of work together, and over eighty electric bells are used for signaling in shafts and on haulages. Such is this marvelous mine, the like of which I doubt whether the world can show. When one considers the enormous capital invested, the elaborate and costly plant, the number of human beings employed, and the object of this unparalleled concentration of effort, curious reflections occur. In all other mining distinctly profitable objects are sought, and purposes are carried out beneficial generally to mankind. This remark would apply to gold mines, to coal mines, to tin, copper, and lead mines; but at the De Beers mine all the wonderful arrangements I have described above are put in force in order to extract from the depths of the ground, solely for the wealthy classes, a tiny crystal to be used for the gratification of female vanity in imitation of a lust for personal adornment essentially barbaric if not altogether savage.