Popular Science Monthly/Volume 54/November 1898/Two Gifts to French Science

| TWO GIFTS TO FRENCH SCIENCE. |

By M. HENRI DE PARVILLE.

M. ANTOINE THOMSON D'ABBADIE, of the Academy of Sciences and Bureau of Longitudes, France, who died in Paris, March 20, 1897, was born in Dublin, January 3, 1810, of a family of the Basses-Pyrénées temporarily residing in Ireland, but which returned to France in 1815. The d'Abbadies are said to have been descended from the lay monks instituted by Charlemagne to defend the frontier against the incursions of the Saracens. The name d'Abbadie was not originally a proper name, but the title of a function (abbatia abbadia), and designated those soldiers who lived in the abbeys of the Basque country, lance in hand. Hence the name, which is well diffused, whether spelled with two bs or one.

While still very young Antoine d'Abbadie manifested an unusual curiosity concerning the unknown around him. "What is there at the end of the road?" he asked his nurse. "A river," she replied. "And what is beyond the river?" "A mountain." "And what then?" "I don't know; I never was there." "Well," said he, "I will go and see." He was the same as he grew up, always wanting to know. He visited Brazil upon a mission for the Academy of Sciences, and on his return joined his brother at Alexandria.

Unknown Ethiopia attracted his attention, and he engaged with his brother Arnould in archaeological researches. Archæology proved unfruitful, and the two brothers took up geodesy. For eleven years Antoine d'Abbadie traveled though Ethiopia, living the life of the natives, and making himself master of the five Abyssinian dialects. The exploration was difficult and sown with dangers. Antoine d'Abbadie covered the country from Massouah, on the shore of the Red Sea, to the interior of the land of Kaffa, which he was the first to visit, with a triangulation that involved the fixing of five thousand positions at five hundred and twenty-five successive stations. The distance between Massouah and Mount Wocho in southern Kaffa is

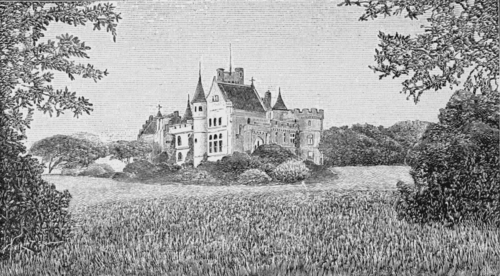

Fig. 1.—Château d'Abbadie. General view. (A gift to the French Academy of Sciences.)

about one thousand kilometres, a little more than the crossing of France along the meridian of Paris, and the trigonometric network reached two hundred and fifty kilometres in breadth. Antoine d'Abbadie remained in Gallaland from 1837 to 1848. The labors of the two brothers, too numerous to cite here, concerned also ethnography and linguistics. Both were nominated Chevaliers of the Legion of Honor on the same day, September 27, 1850. The doors of the Academy of Sciences were opened to Antoine d'Abbadie August 27, 1867, and he was named a member of the Bureau des Longitudes in 1878. He was in charge of the observation of the transit of Venus in Santo Domingo in 1882.

Instead of devoting himself to a specialty, as is done now to excess, d'Abbadie pursued the scientific movement in its various forms, and was at once an astronomer, geodesian, archæologist, ethnographer, numismatist, and interested in other fields. With his noble character he made himself esteemed and loved during his whole working life by all so fortunate as to make his acquaintance. In an interview I had with him a few weeks before his death, when his disease had already gained a strong hold upon him and he was nearly speechless, he expressed himself freely concerning the future, although he uttered every word with difficulty, and it was easy to see that it caused him pain. The topic was science, and he wanted to talk about it.

When he was president of the Academy of Sciences, a few years ago, he sacrificed himself to be equal to the honor that had been conferred upon him. Speaking was already becoming very difficult to his tired vocal organs. He made extreme efforts during the whole year to fulfill his duty as president, and was punctual at the Monday sessions to the end.

In 1896, feeling the advance of age, he determined to make a splendid present to the Academy of Sciences. The Due d'Aumale had given Chantilly to the Institute. M. Antoine d'Abbadie gave the Academy of Sciences his magnificent Chateau d'Abbadie, near Hendaye, in the Basses-Pyrénées, on the coast of the Bay of Biscay. The academy will enter upon the possession of this property, of three hundred and ten hectares of land surrounding it, and of a capital producing a revenue of forty thousand francs (eight thousand dollars) after the death of Madame d'Abbadie. Only a single condition is imposed on the gift. Having carried on his astronomical work at Abbadia and begun there to catalogue the stars and study the variations of gravity, he asked in exchange for his incomparable gift that the academy should complete in fifty years a catalogue of five hundred thousand stars. The bureau of the academy dispatched its president, M. Cornu, and its perpetual secretary, M. Bertrand, to Abbadia as its representatives to express its gratitude to M. and Madame d'Abbadie. The faith of the academy was pledged to continue the work begun by M. d'Abbadie, and a commemorative medal was given him bearing on one side a portrait of Arago, and on the other a minute of the gift and the thanks of the company.

The Château of Abbadia will therefore be devoted to the determination of the stars that are not yet catalogued. Probably, as was the donor's thought, the religious orders or some of the secular priests will perform this colossal labor. The chaplain of the chateau has already given his service to the work. In any case, those who may live in the chateau will have no cause to complain of their home. Abbadia is a very interesting structure, built from plans by Viollet-le-Duc, modified and carried out by the architect Duthoit, with suggestions of the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. The observatory adjoins the chateau, which it antedates thirty years in building, and has a meridian telescope and the essential astronomical instruments. In the deep cellar of the observatory M. d'Abbadie made more than two thousand seismic observations with the pendulum.

The château stands in an admirable situation, and presents a very fine external aspect. We give a general view of it and a picture of the main entrance. The interior decoration is very beautiful.

Those who have had the privilege of visiting Abbadia have remarked that a stone is missing from the balcony of one of the windows; this stone, according to the wishes of the donor, is  Fig. 2.—Principal Entrance to the Château d'Abbadie. never to be put in place. A history is connected with its absence. M. d'Abbadie, in the course of a journey in America, contracted a strong friendship with Prince Louis Napoleon, who was then in the United States. The prince once said to him, "If I ever come into power, whatever you may ask of me is granted in advance." The prince became Emperor of the French. Napoleon III had a good memory. He met his former companion one day, and said to him in an offhand way: "I promised when we were in America to give you whatever you would ask for; have you forgotten it?" M. d'Abbadie replied: "I have built myself a château near Hendaye, where I hope to spend the rest of my days. If you will be so kind as to go a few kilometres out of the way for me during your coming visit to Biarritz, I shall consider myself highly honored if you will lay the last stone of my house." Napoleon smiled and promised. But that was in 1870, and Napoleon III never returned to Biarritz. That is the reason a stone is missing at Abbadia.

Fig. 2.—Principal Entrance to the Château d'Abbadie. never to be put in place. A history is connected with its absence. M. d'Abbadie, in the course of a journey in America, contracted a strong friendship with Prince Louis Napoleon, who was then in the United States. The prince once said to him, "If I ever come into power, whatever you may ask of me is granted in advance." The prince became Emperor of the French. Napoleon III had a good memory. He met his former companion one day, and said to him in an offhand way: "I promised when we were in America to give you whatever you would ask for; have you forgotten it?" M. d'Abbadie replied: "I have built myself a château near Hendaye, where I hope to spend the rest of my days. If you will be so kind as to go a few kilometres out of the way for me during your coming visit to Biarritz, I shall consider myself highly honored if you will lay the last stone of my house." Napoleon smiled and promised. But that was in 1870, and Napoleon III never returned to Biarritz. That is the reason a stone is missing at Abbadia.

An account is also appropriate here of that other gift to French science and letters of the Château of Chantilly, made to the Institute of France in 1886, by the late Duc d'Aumale, whose tragic death in consequence of the terrible disaster at the Bazaar de Charité, Paris, occurred near in time to that of M. d'Abbadie. The duke was conspicuous as a soldier, as a man of letters, the author of the History of the Princes of Condé, and as a great bibliophile; as a member of the French Academy (1871), taking the place of Montalembert; of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, and of the Academy of Fine Arts; and as a patriot, though a banished prince. The gift was made three months after the decree was issued banishing the Orleans princes from France, and after the duke had expostulated with M. Grévy in vain against the step. The deed reads: "Wishing to preserve to France the domain of Chantilly in its integrity, with its woods, lawns, waters, buildings, and all that they contain—trophies, pictures, books, objects of art, and the whole of what forms,

Fig. 3.—The Chateau of Chantilly.

(Presented by the late Due d'Aumale to the Institute of France.)

as it were, a complete and various monument of French art in all its branches, and of the history of my country in its epochs of glory—I have resolved to commit the trust to a body which has done me the honor of calling me into its ranks by a double title, and which, without being independent of the inevitable transformations of societies, escapes the spirit of faction and all too abrupt shocks, maintaining its independence through political fluctuations. Consequently, I give to the Institute of France, which shall dispose of it according to conditions to be hereafter determined, the domain of Chantilly as it shall exist on the day of my death, with the library and the other artistic and historical collections which I have formed in it, the household furniture, statues, trophies of arms, etc." The sole condition attached to the gift was that nothing should be changed at Chantilly. The chapel, where the heart of Condé is deposited, should be retained, devoted to worship, with special masses to be said at stated times, and the splendid collections of the chateau should together be called the Condé Museum. In 1889 the Government authorized the duke to return to France. He refused to accept the permission as a matter of favor, but only as one of right. He returned, however, and took his seat in the academy in May of that year.—Translated for the Popular Science Monthly from articles in La Nature.