Popular Science Monthly/Volume 72/March 1908/A Visit to the Hangchow Bore II

| A VISIT TO THE HANGCHOW BORE |

By Dr. CHARLES KEYSER EDMUNDS

CANTON CHRISTIAN COLLEGE

II

The Great Sea-wall

JUST when and how and at what cost the present substantial seawall was built are now matters for more or less conjecture, the chroniclers of the province neglecting such information as irrelevant in comparison with fanciful legends to be retold in connection with so great a work.[1] One of the most interesting of these stories refers to what was perhaps the first attempt at anything like an adequate sea-wall. It is to the effect that in the region of Emperor Huang Wu (25 A.D.) an official, Hua Hsin, proposing to build a sea-wall opposite the present site of Hangchow, issued a proclamation offering 1,000 "cash" (about fifty cents gold) for every man-load of earth that the people should bring to the river bank. On the appointed day great crowds of men, women and children came to carry earth. At a signal every one took up his load and carried it to the spot indicated by Hua Hsin's lieutenants. At this juncture Hua Hsin himself appeared and, feigning surprise when told of the large wage to be paid per manload, he ordered the people away, saying it was utter nonsense to talk of such high pay. Indignantly the people threw down their loads and walked away, thus unwittingly dropping the earth just where the wily official wanted it. "Thus in one day Hua Hsin, by his trickery, built a sea-wall of great height, and one that withstood the briny waters for many years."

In spite of this assertion of the native chronicler, however, a dyke built in this fashion was sure to prove too flimsy to withstand the impacts of such tides as sweep the bay, and we are not surprised to find frequent references to daily sacrifices and prayers to the Water Dragon for protection against the powerful waters. It was not until the period of the Five Rulers that these prayers were answered by the appearance of a man of works as well as of faith, the "great Prince Ch'ien," Hangchow's most famous man. Many places of interest about the city still bear his name in recognition of his great services to the people, which included besides the less tangible, though none the less real, benefits of a wise and capable government, the more "substantial" benefits arising from the efficient fortification of the

Along a Side Canal.

On a By-way Canal.

(Taken in the rain.)

capital city, the preservation of the West Lake as a water-supply, the building of public roads, institutions of learning and canals, and, in view of the present considerations the most worthy of all, the long sea-wall which stands to-day as the greatest monument to his skill and efficiency in caring for the public weal. Its erection was begun probably about 911 or 915 A.D. It extends from Hangchow to Chuansha near the mouth of the Whang-pu (the river on which Shanghai is situated), a distance of one hundred and eighty miles. It is a stupendous piece of work and deserves an equal share of fame with the Grand Canal and the Great Wall of China, for its engineering difficulties were certainly infinitely greater.

Unfortunately there appears to be no record of how these difficulties were really overcome, although as usual the native historian

(From Decennial Reports C. I. M. C, 1892-1901, Shanghai, 1906.)

the whole being filled with earth and large stones. "Thus he connected the two ends of his wall and shut out the destructive waters," and thus, we may add, does the chronicler avoid telling us the essential details of the very part of the construction, which in its successful accomplishment constitutes the chief wonder.

But it was not enough simply to build the wall; it must be kept in repair, and, curiously enough, the native chroniclers have accounted most minutely for the cost of the up-keep, which is said to be on the

average 250,000 taels per annum, which has led many people of this region to call this sea-wall "China's Second Great Sorrow," giving place to only the Yellow River as her "First Great Sorrow."

For purposes of management and repair the wall is divided into three major divisions with a superintendent over each. These divisions are again divided into many sections about a mile long, and for each mile there are at ordinary times four to six watchmen who patrol their section much as railroads are patrolled.

The first cost of construction must have been enormous, and the mere existence of the wall suffices to show that it must have been of vital importance and that the land it reclaimed and now protects must have been of immense value to justify such an expenditure.

As it exists to-day its total length is one hundred and eighty miles, and for one third of this distance it is faced, as at Haining, with heavy blocks of granite and varies from twenty-five to thirty feet in height above low water. Each successively higher layer of granite slabs recedes about five inches, thus forming steps, a very welcome arrangement when, after descending to get camera views of various parts of the wall just before a bore was due, we had hastily to retreat before the oncoming flood.

The main difficulty in maintaining an efficient sea-wall would seem to be to have an outer footing adequate to break the first violence of the incoming bore and to prevent the undermining of the foundations of the main bunding—in fact it would seem essential that the tides should be entirely kept from entering behind the wall. At Haining the Chinese engineers have succeeded in accomplishing this very satisfactorily in a twofold fashion—viz., by a sea-foot proper and by frequent projecting "buffers," a combination which, besides giving a substantial sea-barrier, also affords excellent and frequent refuges for the junks whose masters must needs brave the dangers and difficulties of navigation in a river so fiercely tide-swept as this is.

At the level of the sixteenth ledge from the top, in this step-like face of the wall just referred to, i. e., about twenty feet below the top of the wall, there extends outward a heavy granite platform several layers deep and about fifteen feet wide. At the outer edge of this several rows of piles are set close together and deeply driven into the river-bed. Here there is a drop of four or five feet followed by another shelving granite platform, somewhat wider than the first and similarly edged with several rows of much heavier and more numerous piles. Here there is a further drop of six or eight feet to a sandy beach which for a yard or two is rock strewn and studded with piles, a ragged fringe of which about ten feet farther out marks the outer edge of this remarkable barrier.

At intervals of half a mile, at least in the immediate vicinity of Haining, huge projecting buffers in semi-elliptical form have been built of brush and piles. The ends of the brush, which has been stacked and interwoven in horizontal layers, are presented on all sides and down through the mass several concentric rings of stout piles have been

driven. These buffers are slightly higher than the sea-wall itself and also extend out beyond the last row of piles which forms the edge of the wall's sea-foot. Topped with earth which affords a rooting place for bushes and small trees, they constitute a notable feature of this very creditable piece of Chinese engineering. Some idea of the destructive force of the bore may be had by inspecting the first buffer east of the pagoda. It is about one third demolished, so that instead of a well-rounded form it now consists of four or five distinct terraces, which are probably constantly settling down and pushing the lower terraces into positions affording less resistance to the tide. On the other hand, the buffer just west of the pagoda is in splendid repair and behind it high up on the topmost granite platform several junks were enjoying a safe shelter.

The stones on the top of the wall are from twelve to sixteen inches wide, sixteen to eighteen inches thick, and from three and a half to four feet long, and most of the blocks used both in the wall and in the platforms of the footing seem equally large. Along the top of the wall adjacent stones are fastened together by heavy iron mortises in the shape of a double wedge (![]() ) four or five inches broad, two linking each pair of stones. Whether the lower layers of blocks are mortised in the same way we were unable to determine, though a friend has reported that he has observed these links also in the slabs forming the footing-platform, but we saw none in the part we examined.

) four or five inches broad, two linking each pair of stones. Whether the lower layers of blocks are mortised in the same way we were unable to determine, though a friend has reported that he has observed these links also in the slabs forming the footing-platform, but we saw none in the part we examined.

On the top of the bunding from Hangchow to beyond Haining, about forty-five miles, there is a broad earth roadway, suitable for riding or even driving, though the latter might be risky, a unique country road. Back of the roadway there is a further embankment some ten feet high and about fifteen or twenty feet thick, which completes the barrier to the encroachment of the boisterous tides. Practically all of the houses near the river are built on levels lower than this bank.

The Haining Pagoda, which has been mentioned already, is apparently not very old and was probably built by a Buddhistic believer in fung shui as a protection to the bund and the city against the ravages of the "serpent's head." It is a fair specimen of its class, and certainly forms the most prominent eminence on that section of the wall, and, together with the more recently constructed pavilion just below it, serves well to mark a vantage point from which to view the approach and passage of the wonderful wave which sweeps past at every tide.

The Bore

We first witnessed the bore on the night of September 5, 1906, really in the early morn of September 6. Arriving at the pagoda at midnight, it was not long before we could distinguish a distant murmur which increased very gradually for an hour, and was the more impressive

because nothing could be distinctly seen, the night, though scheduled for a full-orbed moon, being dark and rainy.

After about half an hour ripples and slight wavelets began coming in just as for an ordinary tide in most places, but with greater rapidity and frequency. At 1 a.m. the murmur had become quite loud and amounted almost to a roar with a sort of thumping; presently the very splash of the on-rush could be heard and at 1:15 a.m. a wall of water passed with a speed of about eight or ten miles an hour, and eight feet high, coming almost straight in along the axis of the river, but curving concavely, and with the highest part in the center. After its transit, the roar was soon lost in the sound of the steady rush of water; then huge and rapid waves and swells came in obliquely with great force, striking the wall at about twenty or thirty degrees and generating a great whirl and splash. This lasted about fifteen minutes and then there was a rather sudden decrease in the size of the rollers, the rising water now being increased by more gentle but still very rapidly moving crests. The inflow was still continuing at 2:30 a.m. when, deserted by our native guides, we were forced to return to our little boat in the canal near by.

The forenoon of September 6 was spent in an examination of the sea-wall for a length of some three miles in the vicinity of the pagoda, the results of which we have already noted.

Evidently we were correct in expecting the bore for that day to be a big one, for a great number of Chinese had come out to witness this never-ceasing wonder, and a considerable group had to judge for themselves of the efficiency of our binoculars in extending the range of vision seaward.

Judging from the ease with which the preliminary murmur had been heard the night before, we were confident of being warned of the formation of the bore in plenty of time to watch its formation from the beginning. But curiously enough this premonitory murmur was not anything like as distinct in the daytime as at night, and while closely examining the structure of one of the brush buttresses, we were surprised by the cries of the natives as they descried to seaward the faint white line which marked the birth of the bore. This was at 12:30 p.m. Bringing our glasses to bear on this line which seemed to be near the meridian of Chishan, a conspicuous hill about twelve miles east by fifteen degrees south from Haining, marking the indentation previously referred to as Bore Shelter Bay, we could see that the bore had formed in two branches. The one on the north side of the channel was considerably the larger and was advancing almost directly up the river, touching the sea-wall with its northern end and the sands with its southern extreme; the other branch was approaching from the southeastward and touched the sands on both sides. The advance line of the first was not so very high, but still we could see it miles away running along the curve of the land, while behind it came a mighty wave, the whole advancing practically at right angles to the northern shore, while the second or southern branch came on almost parallel to the shore and with increasing speed.

This latter line gradually curved around and when about five miles from Haining its northern extreme overtook the southern extreme of the first, thus forming a continuous line of white breakers two or three miles long. Where this juncture was effected great waves, white from the force of impact, dashed many feet into the air in mid-stream and seethed all about the point of conflict. This immense upheaval, however, rather quickly subsided, and the flood wave resumed a more

or less uniform height, which presently increased as the bore contracted in width, and increased in speed as it conformed to the narrowing channel of the river.

With rapidly increasing roar and steady progress this line advanced, and the immensity of the phenomenon began to be appreciated even more than on the previous night. A wall of very muddy water, white crested and fully ten feet high, was approaching with the speed of a railroad train, breaking over and overwhelming the resisting ebb tide of the river, which in front of the pagoda was still running out with a speed of six or seven miles an hour and fighting every foot of the monster's advance. It was a battle of the flood against the ebb, and the flood, backed by the irresistible power of the ocean's rhythmic puise, was swallowing up the ebb with an on-rush which must be seen to be fully appreciated.

At two miles from Haining the flood-stream, probably that from the southeastward which appeared to run through the other, charged into the sea-wall, the violent rebound from which caused a tumultuous upheaval of the waters several hundred yards behind in waves twice as high again as the front of the bore.

As the northern end of the bore struck one of the buttresses, its line of advance was deflected and it came on with a curving and recurving crescent front, the ends being thrown forward of the middle

portion by several hundred yards. This deep graceful curve in the line of the turbulent waters was undoubtedly due, aside from the deflection caused by the buttresses, to the swifter current in the center of the ebb. unwilling to the last to admit defeat.

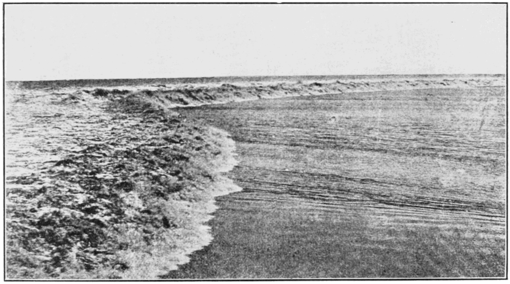

As the bore passed Haining at about 1:45 p. m. it had somewhat the form of a double crescent, over a mile long and eight to eleven feet high, traveling, twelve or thirteen miles an hour; its front a sloping cascade of bubbling foam, falling forward and pounding on itself and on the river before it at an angle of between forty and seventy degrees, the highest and steepest part being about six hundred yards off shore over the deep channel of the river. Close by the northern bank or sea-wall the height and rush were not so great because of the projecting buffers just east of the pagoda, and yet now and again the bore swelled up to the wall as it sped along. The southern end, meeting an incline of sand which rises only nineteen feet in a mile and a half, trailed away in a line of very deliberate breakers, which ceased half a mile to the rear of the bore or where it had passed three minutes before.

A second smaller bore followed directly after the first in the form of a group of secondary rollers on top of the first body of water, and several hundred yards in the rear of the crest behind which for many tens of feet the rushing water was churned into foam by the turmoil. These secondary rollers leaped up from time to time as if struck by some unseen force and disappeared in heavy clouds of spray. These breakers on the top of the flood were sometimes twenty to thirty feet above the level of the river in front of the bore, while the conflict in progress on the river-bed itself was clearly evidenced by the quantities of mud, sand and even large gravel which were seen to be mingled with the surging waters.

The river filled up to the level of the bore soon after it had passed, but not evenly.

A quarter of an hour after the bore had passed Haining, the water had risen thirteen feet; after two hours it had risen eighteen feet; and a high-water mark of nineteen feet was attained at 4:45, or after three hours of flood tide. At this time the stream commenced to run out swiftly. At 6:45 p. m. mean level was reached and at 9:45 it was practically low water again, though the out-going stream continued to run rapidly eastward until the arrival of the midnight bore, the water being at its lowest for the two hours preceding that event.

One of the most surprising features of the whole phenomenon is the sudden change in the aspect of the river. Just now we saw the muddy bottom bare for some distance from the shore to where the mid-river current was swiftly out-flowing, and a few minutes later the whole basin is filled with muddy boiling water, which seems to threaten to wash away even the substantial sea-wall on which we stood.

After the passage of the bore and during the in-rush of the after-body a number of men, some of them probably the duly appointed patrols, others not, appeared on the sea-wall with very long bamboos, some furnished with hooks at the end or spikes, some with rake-heads and others with loops of rope, all designed to enable their manipulators to gather in the driftwood, consisting chiefly of the loosened or broken piles of the outer protecting ledges of the dyke. One fellow was seen marching off in triumph with two whole piles and a half.

During and just after the passage of the bore a busy scene was also enacted on board the junks resting so securely on the platform alongside

the bund and behind the buttress of brush and piles. The bore passed them harmlessly by, merely drenching them with spray. The flood following behind, however, quickly floated them off this place of security, but with a few turns of the ropes, the junks were quickly remoored and continued to ride safely on the racing tide. This accomplished, their loading was hastily completed, and within an hour they were away for a fresh destination up stream, or, waiting two hours longer, were able to effect an outward passage.

It was a curious sight to see the other junks, which previous to the formation of the bore were sheltering in Bore Shelter Bay or behind the islands out beyond the mouth of the river, come riding swiftly

in amid the after-rush, past Haining toward Hangchow, with all sails set but with their bows in every direction. On the days we observed there were each time a baker's dozen of them, but sometimes as many as thirty junks may be seen utilizing tidal energy for ascending the river at a speed exceeding that of an ordinary steam vessel of equal size. As soon as they could steer a little, they made for the shelters behind the buttresses, where they allowed themselves to be stranded by the falling tide.

Steam vessels, not being able to follow the junkmen's method of avoiding the difficulties of navigation, can not use the river. The imminent danger to which those attempting it would be exposed might be inferred from the description we have given, and is clearly shown by the report of Captain Moore, R.N.,[2] who in 1888, in command of H. B. M. ship Rambler and two auxiliary craft, undertook a thorough survey of the river and estuary, which he continued in 1892, and whose vessels narrowly escaped total wreck.

The Birth of the Bore as shown by Observed Water Levels

In this survey observations of water-level were taken simultaneously at three places: Volcano Island, away out at the mouth of Hangchow

from Volcano Island inward to Haining. The rise at Rambler then continued to be very rapid, while the water at Haining remained nearly stationary. This state developed until midnight, by which time the level had risen twenty-one feet at Rambler and about six feet at Volcano, but had not yet risen at all at Haining. Through all this interval the water was running down the river from Haining toward its mouth.

This state of strain represented by a difference in level of over twenty feet between Rambler outside and Haining only twenty-six

miles farther in could not last long, and shortly after mdnight the strain broke down and the bore started somewhere between Rambler Island and Kanpu, and rushed up the river in a wall of water twelve feet high. Following the bore came the after-rush which carried the level up eight feet more. It is on this that the junks are swept up-stream as already noted. At 1:30 the after-rush ceased, but the water was still somewhat higher at Rambler than at Haining, and a gentle current continued up-stream. The water then began to fall at Rambler, while it continued to raise at Haining up to three o'clock, when the ebb set in. On the south bank, at any rate, for four or five miles inside the mouth of the river, the stream commences to run out strongly an hour before high water at Haining. The fall of the water in the ebbing tide is not particularly interesting, for there is no bore down-stream, although at one time there is an exceedingly swift current.

According to the reports of others, the height, speed and characteristic appearance of the bore's front are maintained for fifteen miles above Haining, after which the height decreases; and the wave passes Hangchow city about an hour and a quarter after passing Haining, soon after which it breaks up and gradually disappears, though an effect is reported to be felt at times at Yenchow, some forty miles farther up the river. At Hangchow the rise and fall does not exceed six or seven feet. At Haining, as we have seen, the flood usually lasts three hours; the ebb, nine. At Hangchow the flood continues for only one and a quarter hours and is nearly all in the bore proper.

When the moon is at the point in its orbit nearest the earth at the same time that it is full or new, or when there are strong northerly or easterly winds in the Chusan Archipelago, the bore generally arrives early off Haining, travels at a greater speed than usual, and is also higher. Natives have reported tidal waves at Haining with a height of over thirty feet. As we have already noted, the highest bore is generally expected on the eighteenth of the eighth moon of the Chinese calendar.

Chinese Fancies concerning the Bore

An account of Chinese fancies concerning the tides in general furnished by Professor Giles, may be found in Professor Darwin's book already referred to, and Captain Moore in his report notes a curious legend which ascribes the origin of the bore to the revengeful workings of the spirit of a certain popular general who was assassinated by the Emperor through jealousy of his growing power, and whose body was thrown into the Ch'ien-tang Kiang. Later the Emperor sought to check the devastation of the country which arose from this source by making appeasing sacrifices on the sea-wall; but without effect, and it was at last decided to induce good fung-shui[3] by erecting a pagoda where the worst breach in the embankment had been made. This is the pagoda already frequently referred to and which is still in good condition. "After it was built, the tide, though it still continued to come in the shape of a bore, did not flood the country as before."

Fanciful as these ideas are, it is not at all surprising in view of the awe-inspiring phenomenon which recurs at every tide, and with which the inhabitants have had to cope perhaps from time immemorial, that they should think of it with reverential superstition as the head of a monster serpent which must needs be appeased. As many as five or six thousand people have sometimes assembled on the sea-wall to propitiate the god of the waters by throwing in offerings at a time when the serpent under his control was raging at its highest.

Intermittency of the Bore

This legend taken in connection with the fact that Marco Polo, who in the thirteenth century spent a year and a half in Hangchow, does not include in his account, which otherwise pretends to great minuteness, any reference to the bore seems to Professor Darwin to indicate that the bore is intermittent, because the Emperor referred to is of undoubted historical existence and antedated Marco by some centuries. But Marco Polo's accounts are not to be taken entirely at their face value as to accuracy and faithfulness, and even if the bore did not exist in his time, the great sea-wall which was in all probability built when the Chinese historians claim it was built by Prince Ch'ien, viz., 911-915 A.D., must have existed, and it is hard to conceive how he should have failed to mention such a stupendous public work, especially when he seems to have been so keenly interested in the Grand Canal. Either, as some authorities suggest,[4] Marco Polo never really visited Hangchow, but got his glowing account of the city's wonders from some native poet without admixing the proverbial grain of salt; or else he was so enamoured with the gayeties of life at the capital that he could not spare the time to visit Haining or the lower estuary in person, but judged from afar that there must have been much shipping there, for to this he alludes in several places.

As Professor Darwin finally concludes, it is very uncertain whether the Hangchow Bore has been intermittent, but it is sure that it is liable to considerable variation, for reports by the foreign officers who headed the troops sent against the Taiping rebels show that the intensity of the bore was then (1852-1864) far less than it is to-day. The existence of the bore as well as its fluctuations probably depends on a nice balance between various factors, and the irregularity in the depth and form of the estuary renders impossible the exact calculation of the form of the rising tide. The heading back of the sea water by the natural current of the river, and the progressive change in shape of a wave advancing into shallow water, may combine to produce a rapid rise of the tides in rivers. "But the explanation of the bore as resulting from these causes is incomplete because it leaves their relative importance indeterminate, and serves rather to explain a rapid rise than an absolutely sudden one." "It seems impossible from the mere inspection of an estuary, to say whether there would be a bore there; we could only say that the situation looked promising or the reverse." "... as in many other physical problems, we must rest satisfied with a general comprehension of the causes which produce the observed result." The description we have attempted may serve to give those who have not seen such a wonder some idea of the really marvelous phenomenon, but the best way to become familiar with its characteristics is to go and see it for yourself.

- ↑ For a fuller account of these legends see F. D. Oland's "Hangchow," Shanghai, 1906.

- ↑ "Report on the Bore of the Tsien-Tang-Kiang," London, 1888. "Further Report," etc., 1803. Also, in Proceedings of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1888.

- ↑ Fung-shui, literally "wind-water," a much-used term in Chinese geomancy, signifying propitious influence of the controling spirits involved in any undertaking—perhaps the nearest simple English equivalent is "luck."

- ↑ Decennial Reports, Chinese I. M. Customs, 1892-1901, Vol. II., p. 4.