Popular Science Monthly/Volume 75/October 1909/The Last Census and its Bearing on Crime

| THE LAST CENSUS AND ITS BEARING ON CRIME |

By The Rev. AUGUST DRAHMS

CHAPLAIN OF THE STATE PRISON, SAN QUENTIN, CAL.

THE latest published report of the criminal census of the United States, recently issued, gives an aggregate prison population of 81,772, five hundred and fifty-seven less than a like report for the previous decade ending with the year 1890.

By states the figures present an equally exceptional showing, unexplainable upon the basis of any known law of criminal variation. Thus, among the foremost states that have shown an actual increase in the number of offenders, we have Kansas, 58.2; West Virginia, 50.6; Florida, 40.7, and Washington, 26.6. Twenty of the states, many of them under similar civic, social, climatic and economic conditions, register a marked falling off in the number of such defalcants, notably, New York leading with an actual decrease of 1,606; followed successively by North Carolina, 848; Illinois, 756; Arkansas, 589; Tennessee, 454; Alabama, 450; Arizona, 359; Missouri, 40, and California, 43 prisoners.

The above showing as a whole, would seem to indicate upon the surface a healthy diminution in crime within the last ten years, especially when we consider the fact that the general population of the country has increased during the same period 29.84 per cent, and the criminal status had grown steadily during every previous decade, as set forth by those reports successively, that of 1880, for instance, showing an increase of 78.14 per cent, over that of the previous report; while that of 1890 gives us 40.47 per cent, over that of 1880. The cause assigned for this apparent falling off in crime, however, is set forth in the body of the report as due to the introduction and spread of the probationary system by which the more youthful, and first offenders, are placed under suspended sentences dependent upon good behavior under proper supervisoral care appointed by the court, a wise tentative measure, not without its faults, but infinitely superior to the unconditional detention of this class of offenders at the risk of a still greater immurement in crime at the most impressionable period of their existence.

As to the actual number thus passing under probationary methods we have no way of knowing save from the records of the courts themselves, but they must necessarily be considerable and help to swell materially the general criminal record.

Moreover, a large number of offenders are now sent to the juvenile reformatories who were heretofore included in the jail and penitentiary population, the number in 1890 being 14,846, while in 1904 they had grown to 32,034, an increase of 55 per cent.

These both represent decided movements in advance in the penological systems of the land, approaching more nearly a rational process in the line of treatment and certainly more in accord with the best thought in tentative methods. At least it has this advantage over the old process in that it may cure while the latter is sure to solidify irrevocably into criminal characterization.

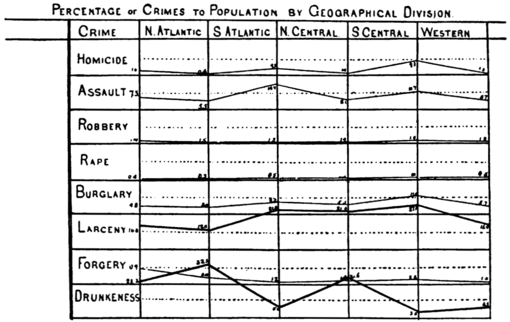

A curious study in the variation of the criminal psychological wave that sweeps over the land, is afforded in tracing the rise and fall of the various grades of offences throughout the different geographical divisions of the United States. A wide divergence in the ratio of the same offences is thus presented with apparently slight differentiation in the social, climatic or economic conditions as manifestly operating causes.

Commencing with grand larceny, which may be considered as a representative type of crime as standing for attack upon property, and we have a wide divergence in the criminal barometer. That form of offence constitutes about 16.8 per cent, of the general bulk of offences in the United States. It finds its lowest manifestation at 12.4 per cent, in the North Atlantic Division, reaching its highest point at 27.1 per cent, in the South Central, and its medium at 15.9 per cent, in the extreme Western Division. In the report of ten years previous it found its maximum in the Western at 61.7 per cent., and its minimum (as at present) in the North Atlantic Division at 24 per cent.

Assault, which may stand for the primitive (atavistic) form of crime in attack upon the person, and we have the lowest in the North Atlantic (5.5 per cent.), and its highest in the South Atlantic at 14.9 per cent. Burglary seems to be the least frequent in the North Atlantic (3.0 per cent.) and most rife in the South Central, where it reaches 11 per cent.

Robbery, the more aggressive form of mixed offenses, contrary to general acceptation, is least rife in the Western Division (1.2 per cent.), and most prevalent in the South Central (18 per cent.), otherwise maintaining a remarkable uniformity throughout the other geographical divisions. In the report of the previous census it reached its climax (13.6 per cent.) in the Western Division. The same may be said of forgery and rape, the latter reaching its apogee in the South Central Division (1.0 per cent.), as against a lesser showing (.05 and.03 per cent., respectively), in the other divisions.

Homicide, the atavistic element in the criminal test, runs its en ensanguined thread through the North Atlantic Division at the rate of .04 per cent.; in the South Atlantic, 4.3 per cent.; in the North Central, 1.4 per cent., and 9.2 per cent, in the South Central, while the "wild and woolly west," contrary to the generally accepted reputation, gives us but 1.5 per cent, of homicides. It has improved in this respect since the date of the previous census (1890) which assigns to that section 27.8 per cent, and to the South Central 22.7 per cent, against its present 4.3 per cent.—a marked veering in the mercurial tendency accountable upon no known law in criminal anthropology.

The total number of homicides in the United States for the year 1904 is given at 10,744, as against 7,351 in 1890, an increase of over 20 per cent, during that period.

As a general rule, the excess of given offences in the southerly divisions is due to the preponderance of the negro element, 67 per cent, of minor offences being attributable to whites, and 83.8 per cent, to the negro race.

Among minor offences drunkenness adds its quota of interest to the general perturbation, oscillating from 5.0 per cent, in the South Atlantic to fever line in the North Atlantic Division at 32.3 per cent., and falling to blood heat at 21.6 per cent, in the North Central, thence to 3.8 per cent, in the South Central and gradually tapering off the mathematical debauch in 6.3 per cent, accredited to the Western Division.

The variation in crime in this respect is no indication of the frequency of the offence, however; it rather reflects the public policy of the given section as expressed in the manner and form of the punishment for this particular offence. There is no special table of the existing habits of the prisoners enumerated, hence no way of reaching any approximate conclusion upon the basis of facts. The census of 1890 gives 23.38 per cent, drunkards among its aggregate prison population, after deducting the number whose habits are "not stated."

Drunkenness is the prevailing habit of criminal offenders, fully 50 per cent, of crimes being due to that habit in this and European countries, perhaps 20 per cent, of the crime in this country being actually committed in the saloons themselves, which are the hotbeds of the criminal propaganda.

The great bulk of crime in the United States, proportionately, is upon the side of the foreign-born population. Succinctly stated, the 13 per cent, of the whole population, representing the foreign-born element, commit 23 per cent, of the crimes in the United States. Precisely the same ratio was reported by the census of 1890. The parentage of this foreign-born element aggregates 29.8 per cent., with a mixed parentage of 6.9 per cent, as against 63.3 per cent, of native-born. The leading nationalities thus represented are Ireland, 36.2 per cent, out of a representation of 15 per cent.; Germany, 12.3 per cent, out of 25 per cent.; Canada, 10.1 per cent, out of 11.4 per cent., and England and Wales, 9.2 per cent, out of 9.10 per cent., of the whole population. As to the more recent arrivals, the Italians furnish 6.1 per cent., with 3.5 per cent, of Russians, and 3 per cent, of Poles. This foreign element is not indigenous to the soil, but belongs to old world criminalism, a form of accretion that does not help swell, but diminishes, proportionately, the list of the country whence it comes. It is characteristic of no other country in making up the criminal consensus.

A careful study of the statistics of the various states show unequivocally the vital relation crime sustains to the two great negative centers of the social disease, viz., ignorance and want. As to illiteracy, that relation is not so apparent in the present as is usually shown by the reports of local institutions. Of the 144,597 committals for the year 1904, 83 per cent, were literates, and 12.6 per cent, were given as illiterates, and 4.3 per cent, not stated. The total percentage of illiterates in the United States was 10.7 per cent.

The occupation of the prisoner is more suggestive. Over 47 per cent, of the white offenders belonged to the laboring classes and servants, and but 3.5 per cent, to the professional and clerical order, while 27 per cent, were credited to the manufacturing and mechanical trades. Among these, it is observable, the professional (to the extent of 2.1 per cent.), and the agricultural portion (to the number of 23.4 per cent.), were more addicted to major than to minor offences, while the laboring classes and servants were more prone to the lesser than to the graver forms, the temptations to the latter being much less in rural districts than in the cities. The largest proportion of offences against the person is found in the rural sections (34.2 per cent.), while those against property predominate in the professional (40.9 per cent.) and the clerical and official (49.8 per cent.) ranks.

These figures present material for the politico-social and economic philosophers, with whom it is left to discover the true points of causal relations and to trace the relative virulence of the social disease as it approaches those great active centers where the struggle for existence grows constantly more intense. In short, the want line focuses the brunt of battle, and here, whatever specific form it assumes, the overt act (that constitutes crime) is most pronounced whether manifested under the world-old principles of greed against need, or in the more purely sporadic form, in either case the burden of the attack may be said to be committed by those who stand nearer the want end of the economic problem, hence the solution must fall more largely to the social and economic phases of the question.

No clear understanding of the criminological problem from either a concrete or academic standpoint is possible without a table of recidivists. This has been omitted from the twelfth census. It renders it valueless to the student of crime. The recidivist table is a method by which we may roughly measure (approximately) the bulk of the criminal aggression and presents the only stable criterion upon which anything like a reliable estimate of the force of the criminal disease may be based with any degree of certainty. Upon its figures alone both the protective and corrective agencies may be said to operate with perfect safety. The repeater has earned his place in the criminal category by inherent right. Recidivism is the classification in the rough by which he is assigned sui generis. The generalization may be crude and not always fair, but it presents the only rule possible under the circumstances. The subtler psychological conditions that underlie human conduct escape utterly any and every analytical process. Every attempted classification upon the basis of accredited conduct must of necessity be but crudely inductive, but it is the only feasible method whereby to differentiate the true criminal from the offender by circumstance.

The latter may not repeat the same act under similar conditions, his inhibitory powers coming to the rescue, the former is almost certain to do so, owing to their lack, or total absence. It is the demarcation between the instinctive and accidental malfeasant. The separation may waste some gold in the process, but in the main the method is correct. At any rate, it is necessary to a complete understanding of the criminal problem and the tentativeness of criminal and corrective measures. It clarifies the former and helps to simplify the latter. The first offender represents an invasion upon the healthy social tissue; the recidivist stands for the already diseased, hence their treatment implies essentially different methods; to the one proper remedial initiatives under wise supervisoral care; to the latter a simple process of sequestration under practical life detention.

The latter cuts off at a single blow the fountain of criminal propagandising protects both society and the offender himself, and is the sole remedial dispensation against the infection. If for no other reason than this, tables that present the problem in clear numerical proportion are a great gain from both a theoretical and a practical standpoint, and its omission is at the expense of both. A marshalling of figures is like the marshalling of an army, it contains the potentialities of victory or defeat, though in the absolute these may be determined by subtler factors.