Popular Science Monthly/Volume 8/March 1876/Lace and Lace-Making

| LACE AND LACE-MAKING.[1] |

By ELIZA A. YOUMANS.

TO think of lace merely as a symbol of vanity is quite to miss its deeper significance. If the feeling that prompts to personal decoration be a proper one—and it is certainly a natural and universal sentiment—then lace has its defense, and we may agree with old Fuller of the seventeenth century, when he says: "Let it not be condemned for superfluous wearing, because it doth neither hide nor heat, seeing that it doth adorn." But the subject has also its graver aspects; for, as science is said to obliterate all difference between great and small, so the history of lace may be said to efface the distinction between the frivolous and the serious. Though good for nothing but decoration, the most earnest elements of humanity have been enlisted in connection with it. Lace-making, a product of the first rude beginnings of art, though complex, and involving immense labor, was yet early perfected. As a source of wealth, it has been the envy of nations and has shaped state policy; as a local industry, it has enriched and ruined provinces; and, as a provocative of invention, it has given rise to the most ingenious devices of modern times, which have come into use only with tragic social accompaniments. The subject has, therefore, various elements of interest which will commend it to the readers of the Monthly.

Lace, made of fine threads of gold, silver, silk, flax, cotton, hairs, or other delicate fibres, has been in use for centuries in all the countries of Europe. But long before the appearance of lace, properly so called, attempts of various kinds were made to produce open, gauzy tissues resembling the spider's web. Specimens of primitive needlework are abundant in which this openness is secured in various ways. The "fine-twined linen," the "nets of checker-work," and the "embroidery" of the Old Testament, are examples. This ornamental needle-work was early held in great esteem by the Church, and was the daily employment of the convent. For a long time the art of making it was a church secret, and it was known as nuns'-work. Even monks were commended for their skill in embroidery.

A kind of primitive lace, in use centuries ago in Europe, and specimens of which are still abundant, is called cut-work. It was made in many ways. Sometimes a network of threads was arranged upon a small frame, beneath which was gummed a piece of fine cloth, open, like canvas. Then with a needle the network was sewed to the cloth, and the superfluous cloth was cut away; hence the name of cut-work. Another lace-like fabric of very ancient date, and known as drawn-work, was made by drawing out a portion of the warp and weft threads from linen, and leaving a square network of threads, which were made firm by a stitch at each corner of the mesh. Sometimes these netted grounds were embroidered with colors.

Still another ancient lace, called "darned-netting," was made by embroidering figures upon a plain net, like ordinary nets of the present day. Lace was also formed of threads, radiating from a common centre at equal distances, and united by squares, triangles, rosettes, and other geometrical forms, which were worked over with a button-hole stitch, and the net thus made was more or less ornamented with embroidery. Church-vestments, altar-cloths, and grave-cloths, were elaborately decorated with it. An eye-witness of the disinterment of St. Cuthbert in the twelfth century says: "There had been put over him a sheet which had a fringe of linen thread of a finger's length; upon its sides and ends was woven a border of the thread, bearing the figures of birds, beasts, and brandling trees." This sheet was kept for centuries in the cathedral of Durham as a specimen of drawn or cut work. Darned-netting and drawn and cut work are still made by the peasants in many countries.

The skill and labor required in the production of these ornamental tissues gave them immense value, and only kings and nobles were able to buy them. But, as this kind of manufacture was encouraged and rewarded by the courts, it reached great perfection centuries ago. A search among court records, and a study of old pictures and monumental sculptures, show that it was much worn in the fifteenth century; but it was not known as lace. The plain or figured network which we call lace was for a long time called passement, a general term for gimps and braids as well as lace, and this term continued in use till the middle of the seventeenth century.

Lace was not only known and worn in the fifteenth century, but its manufacture at that time was an important industry in both Italy and Flanders (Belgium); while in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was extensively made in all the leading countries of Europe. Two distinct kinds of lace were made by two essentially different methods. One was called point-lace, and was made with the needle, while the other was made upon a stuffed oval board, called a pillow, and the fabric was hence called pillow-lace. "On this pillow a stiff piece of parchment is fixed, with small holes pricked through to work the pattern. Through these holes pins are stuck into the cushion.[2] The threads with which the lace is made are wound upon 'bobbins,' small, round pieces of wood, about the size of a pencil, having around their upper ends a deep groove on which the thread is wound, a separate bobbin being used for each thread. By the twisting and crossing of these threads the ground of the lace is formed." The pattern is made by interweaving a much thicker thread than that of the ground, according to the design pricked out on the pattern.

The making of plain lace-net upon the pillow is thus described: "Threads are hung round the pillow in front, each attached to a bobbin, from which it is supplied and acting as a weight. Each pair of adjacent threads is twisted three half-turns by passing the bobbins over each other. Then the twisted threads are separated and crossed over pins on the front of the cushion in a row. The like twist is then made by every adjacent pair of threads not before twisted, whence the threads become united sideways in meshes. By repeating the process the fabric gains the length and width required."

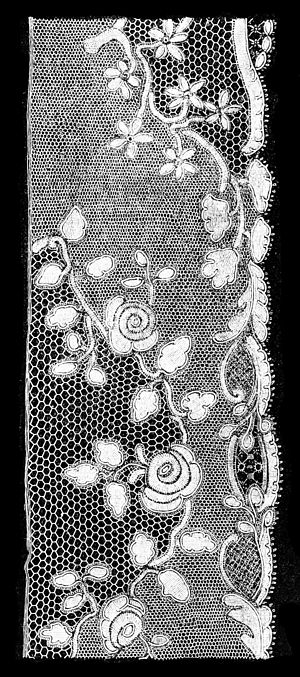

Fig. 1-Valenciennes Lappet. Eighteenth Century

Lace consists of two parts: a network called the ground, and the pattern traced upon it, sometimes called the flower, or gimp (Fig. 1). In modern lace we may easily distinguish the ground and pattern, but in the older laces the flowers are not wrought upon a network

Fig. 2.—Honiton Guipure.

ground, but are connected by irregular threads, overcast with button-hole stitch, and sometimes fringed with loops. These connecting-threads, called "brides," are shown in Fig. 2.

The network ground is known by the French term résau. It is sometimes called entoilage, on account of its containing the toile flower or ornament, which resembles linen, and is often made of linen thread. The terms fond and champ are also applied to it.

The ornamental pattern is sometimes made with the ground as in Fig. 3, or separately, and then worked in or sewed on (appliqué), Fig. 4. The open-work stitches seen in the pattern are called modes, jours, or "fillings."

All lace has two edges, the "footing," a narrow lace which serves to keep the stitches of the ground firm that it may be sewed to the garment upon which it is to be worn (Fig. 3); and the "pearl," picot, couronne, a row of little points or loops at equal distances at the free edsre as shown in the figures.

The manufacture of point-lace was brought to the highest perfection by the Venetians as early as the sixteenth century. The pattern-books

Fig. 3.—Valenciennes lace of Yprès.

of that time contain examples of more than a hundred varieties of this costly lace. Some of these points were world-renowned for their fineness and exquisite beauty. Point de Venice, en relief, is the richest and most complicated of all laces. It is so strong, with its tiers upon tiers of stitches, that some of it has lasted for centuries. All the outlines are in high-relief, and innumerable beautiful stitches are introduced into the flowers. Italian influence under the Valois and Medicis spread the fashion for rich laces, and the Venetian points were in great demand in foreign countries, particularly in France. The exportation of costly laces was a source of great wealth to Venice. The making of lace was universal in every household, and the secret of the manufacture of her finest points she jealously guarded. Although both point and pillow lace were made at this time in all the leading countries of Europe, Flanders was the only rival of Italy in the markets of the world.

During the sixteenth century there was the most extravagant use of lace by the court of France. In 1577, on a state occasion, the king wore four thousand yards of pure gold lace on his dress, and the wardrobe accounts of the queen are filled with entries of point-lace. Such was the prodigality of the nobility at this period in the purchase of lace that sumptuary edicts were issued against it, but edicts failed to put down Venetian points; profusion in the use of lace only increased. The consumption of foreign lace and embroidery was unbounded. Immense sums of money found their way annually from France to Italy and Flanders for these costly fabrics. As royal commands were powerless against the artistic productions of Venice, Genoa, and Brussels, it was determined by Colbert, the French minister, to develop the lace-manufacture in France, that the money spent upon these luxuries might be kept within the kingdom. Skillful workmen were suborned from Venice and the Low Countries, and placed around in the existing manufactories and in towns where new ones were to be established.

Fig. 4.—Old Honiton Application.

A declaration of August 5, 1665, orders "the manufacture of all sorts of works of thread, as well of the needle as on the pillow, in the manner of the points which are made at Venice and other foreign countries, which shall be called 'points de France.'" In a few years a lucrative manufacture was established which brought large sums into the kingdom. Point de France supplanted the points of Venice and Flanders, and France became a lace-making as well as a lace-wearing country.

The manufacture of the most sumptuous of the points de France was established by the minister at the town of Alençon, near his residence. Venetian point in relief was made in perfection in this place before his death, 1683. In all the points of this century the flowers are united à bride (Fig. 2), but in the eighteenth century the network ground was introduced, and soon became universal. The name point de France for French point-lace was after a time dropped, and the different styles took the name of the towns at which they were made, as point d'Alençon and point d'Argentan.

"Point d'Alençon is made entirely by hand with a fine needle, upon a parchment pattern, in small pieces, afterward united by invisible seams. Each part is executed by a special workman. The design, engraved upon a copperplate, is printed off in divisions upon pieces of parchment ten inches long, and numbered in their order. Green parchment is now used, the worker being better able to detect faults in her work than on white. The pattern is next pricked upon the parchment, which is stitched to a piece of very coarse linen folded double. The outline of the pattern is then formed by two flat threads, which are guided along the edge by the thumb of the left hand, and fixed by minute stitches, passed with another thread and needle through the holes of the parchment. When the outline is finished, the work is given over to the maker of the ground, which is of two kinds, bride and réseau. The delicate réseau is worked backward and forward from the footing to the picot. For the flowers the worker supplies herself with a long needle and a fine thread; with these she works the button-hole stitch (point noué) from left to right, and, when arrived at the end of the flower, the thread is thrown back from the point of departure, and she works again from left to right over the thread. This gives a closeness and evenness to the work unequaled in any other point. Then follow the modes and other operations, so that it requires twelve different hands to complete it. The threads which unite linen, lace and parchment are then severed, and all the segments are united together by the head of the establishment. This is a work of the greatest nicety." From its solidity and durability Alençon has been called the Queen of Lace.

The manufacture of Alençon lace had greatly declined even before the Revolution, and was almost extinct when the patronage of Napoleon restored its prosperity. On his marriage with the Empress Marie Louise, among other orders executed for him was a bed furniture—tester, curtains, coverlet, and pillow-cases, of great beauty and richness. The pattern represented the arms of the empire surrounded by bees. Fig, 5 is a piece of the ground powdered with bees. The differences of shading seen in the ground show where the separate bits of lace were joined in the finishing. With the fall of Napoleon this manufacture again declined, and, when in 1840 attempts were made to revive it, the old workers, who had been specially trained to it, had passed away, and the new workers could not acquire the art of making the pure Alençon ground. But they made magnificent lace, and Napoleon III. was magnificent in his patronage of the revived manufacture. One flounce worth 22,000 francs, which had taken thirty-six women eighteen months to finish, appeared among the wedding-presents of Eugenie. In 1855 he presented the empress with a dress of Alençon point which cost 70,000 francs ($14,000). Among the orders of the emperor in 1856 were the curtains of the imperial infant's cradle, of needle-point, and a satin-lined Alençon coverlet; christening robe, mantle, and head-dress, of Alençon; twelve dozen embroidered frocks profusely trimmed with Alençon; and lace-trimming for the aprons of the imperial nurses. The finest Alençon point is now made at Bayeux.

Argentan is another town in France celebrated for its point-lace, which was not inferior in beauty to that of Alençon. The flowers of

Fig. 5.—Alençon Bed made for Napoleon I.

point d'Argentan, as seen in Fig. 6, are large and bold, in high-relief, on a clear compact ground, with a large, six-sided mesh. This ground was made by passing the needle and thread around pins pricked into a parchment pattern, and the six sides were worked over with seven or eight button-hole stitches on each side. It is called the grande bride ground, and is very strong.

While it is clear that France derived the art of making Alençon point from Italy, yet, along with all the countries of Northern Europe, Germany, and England, she is in the main indebted to Flanders for her knowledge of the art of lace-making. Flanders, as well as Italy,

Fig. 6.—Point d'Argentan.

claims the invention of lace, and, notwithstanding its glorious past, the lace-trade of Belgium is now as flourishing as at any former period.

Fig. 7.

Brussels lace is widely known as point d'Angleterre, for the reason, it is said, that in the seventeenth century the English, after vainly attempting to establish its manufacture at home, bought up the finest laces of the Brussels market, smuggled them over to England, and sold them as English point (Figs. 7 and 8).

The smuggling of lace is a very important and interesting feature in its history. From 1700 downward we are told that in England the prohibition of lace went for nothing. Ladies would have foreign lace, and if they could not smuggle it themselves the smuggler brought it to them. "Books, bottles, babies, boxes, and umbrellas, daily poured out their treasures." Everybody smuggled.

"At one period much lace was smuggled into France from Belgium by means of dogs trained for the purpose. A dog was caressed and petted at home, fed on the fat of the land, then, after a season, sent across the frontier where he was tied up, half starved, and ill-treated. The skin of a bigger dog was then fitted to his body, and the intervening space filled with lace. The dog was then allowed to escape, and make his way home, where he was kindly welcomed, with his contraband charge. These journeys were repeated till the French custom-house, getting scent, by degrees put an end to the traffic. Between 1820 and 1836, 40,278 dogs were destroyed, a reward of three francs being given for each."

The thread used in Brussels lace is of the first importance. It is of extreme fineness, and the best quality, spun in underground rooms to avoid dryness of the air, is so fine as to be almost invisible. The room is darkened, and a background of dark paper is arranged to throw out the thread, while only a single ray of light is admitted, which falls upon it as it passes from the distaff". The exquisite fineness of this thread made the real Brussels ground so costly as to prevent its production in other countries. A Scotch traveler, in 1787, says that "at Brussels, from one pound of flax alone, they can manufacture to the value of seven hundred pounds sterling."

In former times, the ground of Brussels lace was made both by needle and on the pillow. The needle-ground was worked from one flower to another, while the pillow-ground was made in small strips an inch wide, and from seven to forty-five inches long. It required the greatest skill to join the segments of shawls and large pieces of lace. The needle-ground is three times as expensive as the pillow, for the needle is passed four times into each mesh, but in the pillow it is not passed at all. Machinery has now added a third kind of ground, called tulle, or Brussels-net. Since this has come into use, the hand-made ground is seldom used except for royal trousseaux. The flowers of Brussels lace are also both needle-made point à l'aiguille and those of the pillow "point plat." In the older laces the plat flowers were worked in along with the ground, as lace appliqué was unknown (Figs. 7 and 8).

Each process in the making of Brussels lace is assigned to a different hand. The first makes the vrai réseau; the second the footing; the third makes the point à l'aiguille flowers; the fourth, the plat flowers; the fifth has charge of the open-work (jours) in the plat; the sixth unites the different pieces of the ground; and the seventh sews

Fig. 8.—Old Brussels (Point d/Angleterre). Middle of Eighteenth Century.

the flowers upon the ground (application). The master prepares the pattern, selects the ground, and chooses the thread, and hands all over to the workman, who has no responsibility in these matters. "The lace industry of Brussels is now divided into two branches, the making of sprigs, either point or pillow, for application upon the net-ground, and the modern point gaze. The first is the Brussels lace, par excellence, and more of it is produced than of any other kind. Of late years it has been greatly improved by mixing point and pillow-made flowers.

Point gaze is so called from its gauze-like needle-ground, fond gaze, comprised of very fine, round meshes, with needle-made flowers, made simultaneously with the ground, by means of the same thread, as in the old Brussels. It is made in small pieces, the joining concealed by sprigs or leaves, like the old point, the same lace-worker making the whole strip from beginning to end. Point gaze is now brought to the highest perfection, and is remarkable for the precision of the work, the variety and richness of the jours, and the clearness of the ground. It somewhat resembles point d'Alençon, but the work is less elaborate and less solid. Alençon lace, it is said, could not compete with Brussels in its designs, which are not copied from Nature, while the roses and honeysuckles of the Brussels lace are worthy of a Dutch painter. When flowers of both pillow and needle-lace are marked upon the "fond gaze it is erroneously called point de Venice."

Lace-making is at present the chief source of national wealth in Belgium. It forms a part of female education, and one-fortieth of the entire population (150,000 women) are said to be engaged upon it.

But some of the pillow-laces have had immense popularity as well as those of the needle. Fig. 1 is a beautiful example of the pillow-lace made at Valenciennes in the eighteenth century.

This kind of lace was first made in the city of Valenciennes, and the manufacture reached its height in that town about 1780, when there were some 4,000 lace-makers employed upon it; but fashion changed, lighter laces came into vogue, and in 1790 the lace-workers had diminished to 250. Napoleon made an unsuccessful attempt to revive the manufacture, and in 1851 only two lace-makers remained, and they were over eighty years old. At one time this manufacture was so peculiar to the place that it was said, "if a piece of lace were begun at Valenciennes and finished outside the walls, the part not made at Valenciennes would be visibly less beautiful and less perfect than the other, though done by the same lace-maker with the same thread and pillow," The city-made lace was remarkable for its richness of design, evenness, and solidity. It was known as the "beautiful and everlasting Valenciennes," and was bequeathed from mother to daughter like jewels and furs. It was made by young girls in underground rooms, and many of these workers are said to have become almost blind before they were thirty years of age When the whole piece was done by the same hand the lace was thought much more valuable. Valenciennes lace was made in other towns of the province, but "vraie Valenciennes" only at Valenciennes. The Lille makers, for instance, would make from three to five ells a day (an ell is forty-eight inches), while those of Valenciennes would make not more than an inch and a half in the same time. Some lace-makers made only twenty-four inches in a year; hence the costliness of the lace. Modern Valenciennes is far inferior in quality to that made in 1780.

The manufacture is now transferred to Belgium, to the great commercial loss of France, for it is the most widely consumed of any of the varieties of lace. It is the most important of the pillow-laces of Belgium. Yprès, which is the chief place of its manufacture, began to make this lace in 1656. In 1684 it had only three forewomen and 63 lace-makers, while in 1850 it numbered from 20,000 to 22,000. The Valenciennes of Ypres (Fig. 3) is the finest and most elaborate of any that is now made. On a piece not two inches wide, from 200 to 300 bobbins are employed, and for greater widths 800 bobbins are sometimes used on the same pillow. The large, clear squares of the ground contrast finely with the even tissue of the patterns. The Yprès manufacture has greatly improved since 1833, and has reached a high degree of perfection. Irish Valenciennes closely resembles the Yprès lace. Valenciennes lace as fine as that of France was at one time made in England (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.—Valenciennes, Northampton, England.

Mechlin is a fine, beautiful lace, made in one piece on the pillow, and is distinguished by the flat thread which forms its flower. Before 1665 all pillow-lace, of which the pattern was relieved by a flat thread, was known as Mechlin lace. "It is essentially a summer lace, not becoming in itself, but charming when worn over color."

Silk laces were first made about 1745. At first this new fabric was manufactured from silk of the natural color brought from Nanking and it was hence called blonde. After a time, however, it was prepared from the purest and most brilliant white silk. "Not every woman can work at the white lace. Those who have what is locally termed the haleine grasse (greasy breath) are obliged to confine themselves to black." To preserve purity of color it is made in the open air in summer, and in winter in the lofts over cow-houses, as the warmth of the animals enables the workers to dispense with fire, which makes more or less smoke. The most beautiful blondes were once made at Caen, but competition with the machine-made blondes of Calais and Nottingham has caused the manufacture of white blonde to be abandoned at this place, and its lace-makers now confine themselves to making black lace.

The manufacture of black-silk lace was first established in the town of Chantilly, near Paris, and hence, wherever this fabric is now made, it is called "Chantilly lace." It is always made of a lustreless silk, called "grenadine," which is commonly mistaken for thread. As it was only consumed by the nobility, its unfortunate producers became the victims of the Revolution of 1793, and perished with their patrons on the scaffold. This put an end to the manufacture for many years; but in 1835 black lace again became fashionable, and Chantilly was once more prosperous. But the nearness of Chantilly to Paris has, of late, increased the price of labor so much that the lace-manufacturers have been driven away. The so-called Chantilly shawls are now made at Bayeux. The shawls, dresses, and scarfs, that are still made at Chantilly are mere objects of luxury.

The black laces of Caen, Bayeux, and Chantilly, are identical. The shawls, dresses, flounces, veils, etc., are made in strips and united by a peculiar stitch. Great pains are taken in Bayeux in the instruction of lace-makers, so that the town now leads in the manufacture of large pieces of black lace. Fig. 10 represents a sample of this lace of the finest quality and of rich design.

Each country has furnished its special style of lace—Italy its points of Venice and Genoa; Flanders its Brussels, Mechlin, and Valenciennes; France its point d'Alençon and its black lace of Bayeux. England has also produced its unique Honiton, and Spain its silk blondes. Each of these laces is made in other countries, but in its characteristic lace each nation is unrivaled.

Honiton lace, the only original English lace of importance, was first made at Honiton, in Devonshire, in the seventeenth century. The art of lace-making is said to have been brought into England by Flemish refugees, and Honiton lace long preserved an unmistakable Flemish character. It is to its sprigs that it owes its reputation. They are made separately, and at first they were worked in with the pillow-ground; afterward they were sewed on, as shown in Fig. 4, which is a sample of the Honiton of the last century. The net is very beautiful and regular. It is made of the finest thread, brought from Antwerp at a cost of $350 per pound. There was no thread to be found in the British Islands fit for the purpose. Cotton thread, perhaps, might be had, but not the linen thread necessary in a work requiring so much labor, which alone would make it very costly. The manufacture of a piece of net like this, eighteen inches square, cost $75, and a Honiton veil often cost a hundred guineas.

At the time of the marriage of Queen Victoria, the manufacture of Honiton lace was so depressed that it was with difficulty the necessary number of lace-workers could be found to execute the wedding

Fig. 10.—Black Lace of Bayeux.

lace. Her dress cost £1,000, and was composed entirely of Honiton sprigs, connected on the pillow by a variety of open-work stitches. Fig. 11 is one of the honeysuckle sprigs from a flounce afterward made for her Majesty. "The bridal dresses of their royal highnesses the Princess Royal, the Princess Alice, and the Princess of Wales, were all of Honiton lace, the patterns consisting of the national flowers, the latter with prince's-feathers intermixed with ferns, and introduced with the most happy effect." These sprigs are joined with the needle by various stitches, forming Honiton guipure, Fig. 2, which, in richness and delicacy, is by many thought to surpass the fine

Fig. 11.—Honeysuckle Sprig of Modern Honiton.

guipure of Belgium, known as duchesse lace. "The reliefs are embroidered with the greatest delicacy, and the beauty of the workmanship is exquisite."

Valenciennes and Mechlin were the first laces in which the ground was wrought in one piece with the design. Until this time all lace had been guipure—that is, it had consisted of open embroidery, in which the figures were connected by brides without any thing like a background. The network ground, which we now take to be the essential thing in lace, was not thought of till the end of the seventeenth century. The word guipure means a thick cord over which silk, gold, or silver thread, is twisted. In the seventeenth century this guipure, or guipé, was introduced into lace to imitate the high-reliefs of needle-made points. These were guipure laces. The name has since been applied to all laces without grounds that have the patterns united by brides. The bold, flowing figures of Belgium and Italy, joined by a coarse network ground (Fig. 12), are also called guipure.

The guipure called Cluny, with its geometrical patterns, is a recent lace which derives its name from the circumstance that the first patterns were copied from specimens of old lace in the Musée de Cluny.

Thus far we have only spoken of hand-made lace, which, in Italy, was a purely domestic industry. It was made by women at home,

Fig. 12.—Guipure. Seventeenth Century.

and each piece of work was begun and finished by the same hand. But, when the statesman Colbert introduced the manufacture into France, the principle of the division of labor was adopted, and the work was done in large factories. By degrees, as we have seen, fine needle-made net replaced the bride-ground in costly laces, and cheaper laces of the same style were made upon the pillow. The sprigs were at first worked into the net; but at length, in the Valenciennes and Mechlin laces, the figure was made along with the ground, and it was the immense success of these laces which led to the invention and perfection of lace-machines, so that now almost every kind of lace is made by machinery, and often so perfect that it is difficult for experts to detect the difference.

"The number of new mechanical contrivances to which this branch of manufacture has given rise is altogether unparalleled in any other department of the arts." It was in 1764, a little more than a hundred years ago, that pillow-made net was first imitated by machinery. It was called frame-looped net, and was made by using one thread, as in hosiery, and, like hosiery, the lace would ravel when this thread was broken. The machine was, in fact, a modification of the stocking-frame. It was so much improved from time to time that net with six-sided meshes could be made, which, when stiffened, looked like cushion-net, but when damp it would shrink like crape.

Another machine was devised for making lace, called the warp-frame. The lace made by it, like the former, consisted of looped stitches, but a solid web was produced, which could be cut and sewed like cloth. In 1795 lace open-work was made by this machine, and soon afterward durable and cheap figured laces, in endless variety. "The lightest gossamer blond silk laces, cotton tattings and edgings, antimacassars and d'oyleys, threaded and pearled, are finished in this loom, and are the pioneers of higher-priced lace articles throughout the world. In 1810 there were four hundred warp-looms at work making the lace called Mechlin-net, and using cotton yarn costing fifteen guineas the pound."

But the most important step ever taken in the making of lace was the invention of the bobbin-net machine. Until this invention machine-lace was, for the most part, only a kind of knitting that had to be gummed and stiffened to give it the solidity of net. The great problem of the time was how to imitate pillow-made net by machinery. Numerous attempts to do this were made by smiths, weavers, and lace-makers. Much inventive talent was vainly spent, and many men of genius fell into poverty through their prolonged and unrequited efforts to construct the required machine. Insanity and self-destruction had ended the careers of some, and disappointment and misfortune befell them all, until at last the idea of such a machine was regarded as visionary it was classed with the perpetual motion.

John Heathcote, the inventor of the bobbin-net machine, was born in 1783. In youth he was remarkable for his quick acquisition of knowledge, his thoughtful intelligence, and quiet deportment. He was early placed at the hosiery manufacture, and at the age of sixteen he conceived the idea of constructing a machine to make lace. In 1804 he was at work as a journeyman at Nottingham, and is thus described by his employer: "Heathcote showed that he had already attained to a thorough knowledge of mechanical contrivances; was inventive and persevering; undaunted by difficulties or mistakes and consequent ill-success; patient, self-denying, and very taciturn. But he expressed surprising confidence that, by the application of mechanical principles to the construction of a twist-net machine, his efforts would be crowned with success." Being determined to construct a machine for making twisted and traversed net[3], he removed to a place where he could secure privacy and the constant sight of lace-making upon the pillow. During the time between 1805 and 1808 he perfected and patented his first machine, by which he could make a breadth of traversed and twisted net three inches wide. It was pronounced by Lord Lyndhurst "the most extraordinary machine ever invented; but he at once broke it up, and in 1809 patented another, which would make a wider net and had many other advantages.

"Cushion-made net had half the threads proceeding in wavy lines from end to end of the piece, and may be represented by warp-threads. The other threads, lying between the former, pass from side to side by an oblique course to the right and left, and may be called weft-threads. If the warp-threads could move relatively to the weft-threads so as to effect the twisting and crossing, but without deviating to the right or left hand, and if the weft-threads could be placed so that all of them should effect the twisting at the same time, and one-half of them should proceed at each operation to the left and the other half to the right hand (a substitute being also provided for the cushion-pins), lace would be made exactly as on the cushion," The machine patented by

Fig. 13.

Heathcote secured these results, and increased the production over the pillow-worker a thousand-fold. The courses of the threads forming the meshes of the bobbin-net frame may be seen in Fig. 13. When taken off and extended to their proper shape the meshes have the appearance shown in Fig. 14.

This wonderful machine was produced by the unaided mechanical skill of Heathcote; but in constructing it he met with such difficulties as led him long after to say that, "if it were to be done again, he should probably not attempt to overcome them." He was only twenty-six years old when he took the second patent. In 1813 he patented various improvements upon it and reduced the number of movements necessary to make a row of meshes. The machine of 1809 employed sixty movements to make one mesh, which is now done by twelve. It made one thousand meshes a minute, and only five or six could be made by hand. A machine of the present day produces thirty thousand in the same time. This industry is said to surpass all others in the complex ingenuity of its machinery.

One of the machines used in its production is said by Dr. Ure to be as much beyond the most curious chronometer in multiplicity of mechanical device as that is beyond a common roasting-jack.

In 1811, when prices had fallen, a Vandal association at Loughborough paraded the streets at night with their faces covered, and armed with swords and pistols, and, entering the workshops, they broke the machines with hammers; twenty-seven machines were destroyed in Heathcote's factory. In 1816 fifty-five more were destroyed

Fig. 14.

by the same society. Of the eight men who conspired in the attack on Heathcote's factory, six were convicted and hung and two transported for life. Heathcote's loss was estimated at $50,000, which the authorities offered to make up to him if he would reëxpend the money in the county. This he refused to do, and the result was that he left Loughborough and settled at Tiverton, where he remained until his death in 1861. Heathcote employed his mechanical skill with unwearied energy in improving the lace-manufacture. From 1824 to 1843 he was constantly busy with inventions, and he represented Tiverton in Parliament from 1834 to 1859.

"Bobbin-net and lace are cleaned from the loose fibres of the cotton by the ingenious process of gassing, as it is called, invented by the late Mr. Samuel Hall, of Nottingham. A flame of gas is drawn through the lace by means of a vacuum above. The sheet of lace passes to the flame opaque and obscured by loose fibre, and issues from it bright and clear, not to be distinguished from lace made of the purest linen thread, and perfectly uninjured by the flame." The progressive value of a square yard of plain cotton bobbin-net is thus stated: In 1809, $25; 1813, $10; 1815, $7.50; 1818, $5; 1821, $3; 1824, $2; 1827, $1; 1830, 50 cents; 1833, 32 cents; 1836, 20 cents; 1842, 12 cents; 1850, 8 cents; 1856, 6 cents; 1862, 6 cents.

In 1823, when Heathcote's patent expired, water and steam power had already began to take the place of hand-labor, and lace-machines rapidly increased in numbers. Men of all ranks and professions, clergymen, lawyers, and doctors, embarked capital in the business, and all Nottingham went mad. Mechanics flocked to the scene, dwellings could not be had, and building-ground sold for $20,000 an acre. "Thousands of pounds were paid in wages to men who had not seen a twist-machine, and tens of thousands for machinery that could never repay the outlay. Improvident men rode to their work, stopping for drinks of port and claret by the way, and were seen years afterward receiving parish pay. When the national frenzy of 1825 collapsed, the effect of this local inflation was fearful. Visions of wealth were at once dissipated; many in and out of the trade fell into poverty, or became exiles, and some destroyed themselves."

The extent of the manufacture of lace by machinery in England is immense. In 1866 there were 3,552 bobbin and 400 warp machines, yielding £5,130,000. There has been no actual census since then, but in 1872 the returns were certainly not less than £6,000,000.

In France, in 1851, there were 235,000 cushion-lace makers, producing annually £3,000,000, the whole European production in hand-made lace being £5,500,000. The bobbin-net machines and warp frames are extensively used in France, and twenty years ago there were 50 bobbin-net machines in Belgium, making very fine extra twist-net on which cushion sprigs are applied.

The invention of machinery for lace-making, however, has not diminished the consumption of costly hand-made laces. The rich seem more eager than ever to obtain the finer products of the needle and pillow, insisting that the touch, finish, and beauty, of such laces can never be attained by the products of the lace-frame. On the contrary, the writer was recently assured, by the foreman of a leading lace establishment in London, that no hand-made ground could compare in beauty and perfection of workmanship with some of the exquisite grounds now made by machinery.

- ↑ We cannot give a complete account of lace in a magazine article, but readers who desire more information are referred to Mrs. Palliser's excellent history of the subject, to which we are largely indebted, and from which our illustrations are mostly taken.

- ↑ Sometimes lace-makers who were the wives of fishermen, not being able to buy pins, used the bones of fish as substitutes. Hence the term bone-lace.

- ↑ Net in which great numbers of threads were made to twist with or wrap round each other, and to traverse, mesh by mesh, through a part or the entire width of the frame.