The Beginner's American History/Chapter 29

XXIX. Since the Civil War

- John Cabot discovers the continent of North America.

- Celebration of the discovery of America by Columbus.

- Our Hundred Days' War with Spain.

- The rebellion in Cuba.

- The destruction of the Maine.

- Declaration of war and the blockade of Cuba.

- Dewey's victory at Manila.

- Cervera “bottled up”; Hobson's brave deed.

- Fighting near Santiago; the “Rough Riders”; Cervera caught.

- The end of the war; what the “Red Cross Society” did.

- The murder of President McKinley.

- The unfinished pyramid; making history.

Since the Civil War[edit]

263. How the North and the South have grown since the war; the great West.— Since the war the united North and South have grown and prospered1 as never before. At the South many new and flourishing towns and cities have sprung up. Mines of coal and iron have been opened, hundreds of cotton-mills and factories have been built, and long lines of railroads have been constructed.

The Meeting of the Engines from the East and the West after the Last Spike was driven on the Completion of the First Railroad to the Pacific in 1869

The last spikes (one of gold from California, one of silver from Nevada, and one made of gold, silver, and iron from Arizona) were driven just as the clock struck twelve (noon) on May 10th, 1869, at Promontory Point, near Salt Lake, Utah. Every blow of the hammer was telegraphed throughout the United States.

Indians attacking a Stage-Coach in the Far West Forty Years ago, before the First Pacific Railroad was built

At the West even greater changes have taken place. Cities have risen up in the wilderness, mines of silver and gold have been opened, and immense farms and cattle ranches2 produce food enough to feed all America. Five great lines of railroads have been built which connect with railroads at the East, and stretch across the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Into that vast country beyond the Mississippi, hundreds of thousands of industrious people are moving from all parts of the earth, and are building homes for themselves and for their children.

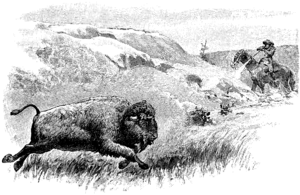

How they used to shoot Buffalo in the Far West

264. Celebration of the discovery of America by Columbus.— More than four hundred years have gone by since the first civilized man crossed the ocean and found this new world which we call America. In 1893 we celebrated that discovery made by Columbus, not only in the schools throughout the country, but by a great fair—called the “World's Columbian Exposition”—held at Chicago. There, on the low shores of Lake Michigan, on what was once a swamp, the people of the West had built a great city. They had built it, too, where a United States government engineer had said that it was simply impossible to do such a thing, and in 1893 Chicago had more than a million of inhabitants. Multitudes of people from every state in the Union visited the exposition, and many came from all parts of the globe to join us.

265. Our Hundred Days' War with Spain.3— A little less than five years after the opening of the Columbian Exposition we declared war against Spain. It was the first time we had crossed swords with any nation of Europe since General Jackson won the famous battle of New Orleans (see Chapter 23) in the War of 1812 with Great Britain.

When Major McKinley became President (1897) we had no expectation of fighting Spain. The contest came suddenly, and Cuba was the cause of it. Spain once owned not only all the large islands in the West Indies, which Columbus had discovered (see Chapter 1), but held Mexico and Florida, and the greater part of that vast country west of the Mississippi, which has now belonged to the United States for many years. Piece by piece Spain lost the whole of these enormous possessions, until at last she had nothing left but the two islands of Cuba and Porto Rico.

266. The rebellion in Cuba.— Many of the Cubans hated Spanish rule, and with good reason. They made several attempts to rid themselves of it and fought for ten years (1868–1878), but without success. Finally, in the spring of 1895, they took up arms again, and with the battle cry of “Independence or death!” they set to work in grim earnest to drive out the Spaniards. Spain was determined to crush the rebellion. She sent over thousands of soldiers to accomplish it. The desperate fight continued to go on year after year, until it looked as though the whole island—which Columbus said was the most beautiful he had ever seen—would be converted into a wilderness covered with graves and ruins. In the course of the war great numbers of peaceful Cuban farmers were driven from their homes and starved to death; and many Americans who had bought sugar and tobacco plantations saw all their property, worth from $30,000,000 to $50,000,000, utterly destroyed.

267. The destruction of the Maine.— Cuba is about the size of the State of Pennsylvania. It is our nearest island neighbor on the south, and is almost in sight from Key West, Florida. The people of the United States could not look on the war of devastation unmoved. While we were sending ship-loads of food to feed the starving Cubans, it was both natural and right that we should earnestly hope that the terrible struggle might be speedily brought to an end.

Our Government first urged and then demanded that Spain should try to make peace in the island. Spain did try, tried honestly so far as we can see, but failed. The Cuban Revolutionists had no faith in Spanish promises; they positively refused to accept anything short of separation and independence. Spain was poor and proud; she replied that come what might she would not give up Cuba.

While we were waiting to see what should be done a terrible event happened. We had sent Captain Sigsbee (Sigs′bee) in command of the battle-ship Maine to visit Havana. In the night (February 15, 1898), while the Maine was lying in that port, she was blown up. Out of three hundred and fifty-three officers and men on board the vessel, two hundred and sixty-six were instantly killed, or were so badly hurt that they died soon after. We appointed a Court of Inquiry, composed of naval officers, to examine the wreck. After a long and careful investigation of all the facts, they reported that the Maine had been blown up by a mine4 planted in the harbor or placed under her hull. Whether the mine was exploded by accident or by design, or who did the fatal work, was more than the Court could say.

Map of the World showing all the Possessions of the United States, including Islands

268. Declaration of war and the blockade of Cuba.— President McKinley sent a special message to Congress in which he said, “The war in Cuba must stop.” Soon afterward Congress resolved that the people of Cuba “are, and of right ought to be, free and independent.”5 They also resolved that if Spain did not proceed at once to withdraw her soldiers from the island, we would take measures to make her do it. Spain refused to withdraw her army, and war was forthwith declared by both nations.

The President then sent Captain Sampson6 with a fleet of war-ships to blockade Havana and other Cuban ports, so that the Spaniards should not get help from Spain to carry on the contest. He next put Commodore Schley (Shlī) in command of a “flying squadron” of fast war-vessels, so that he might stand ready to act when called upon.

269. Dewey's victory at Manila.— In the Pacific Spain owned the group of islands called the Philippines.7 Many of the people of those islands had long been discontented with their government, and when the Cubans rose in revolt against Spain it stirred the inhabitants of the Philippines to begin a struggle for liberty. They, too, were fighting for independence.

President McKinley resolved to strike two blows at once, and while we hit Spain in Cuba, to hit her at the same time at Manila (Man-il′ah), the capital of the Philippines. It happened, fortunately for us, that Commodore Dewey8 had a fleet of six war-ships at Hong Kong, China. The President telegraphed to him to start at once for Manila and to “capture or destroy” the Spanish fleet which guarded that important port. The Spaniards at that place were brave men who were determined to hold Manila against all attack; they had forts to help them; they had twice as many vessels as Commodore Dewey had; on the other hand, our vessels were larger and better armed; best of all, our men could fire straight, which was more than the Spaniards knew how to do.

Commodore Dewey carried out his orders to the letter. On the first day of May (1898) he sent a despatch to the President, saying that he had just fought a battle and had knocked every Spanish war-ship to pieces without losing a single man in the fight. The victorious Americans took good care of the wounded Spaniards.

The President at once sent General Merritt from San Francisco with a large number of soldiers to join Commodore Dewey. Congress voted the “Hero of Manila” a sword of honor, and the President, with the consent of the Senate of the United States, made him Rear-Admiral, and later Admiral, thus giving him the highest rank to which he could be promoted in the navy.

270. Cervera “bottled up”; Hobson's brave deed.— Spain had lost one fleet, but she still had another and a far more powerful one under the command of Admiral Cervera (Sur-vee′rah). Where Cervera was we did not know—for anything we could tell he might be coming across the Atlantic to suddenly attack New York or Boston or some other of our cities on the Atlantic coast. The President sent Commodore Schley with his “flying squadron” to find the Spanish fleet. After a long search the Commodore discovered that the Spanish war-ships had secretly run into the harbor of Santiago (San-te-ah′go) on the southeastern coast of Cuba.

A day or two afterward Captain Sampson with a number of war-vessels went to Santiago and took command of our combined fleet in front of that port. One of Captain Sampson's vessels was the famous battle-ship Oregon, which had come from San Francisco round South America, a voyage of about thirteen thousand miles, in order to take a hand in the coming fight.

The entrance to the harbor of Santiago is by a long, narrow, crooked channel guarded by forts. We could not enter it without great risk of losing our ships. It was plain enough that we had bottled up Cervera's fleet, and so long as Cervera remained there he could do us no harm. But there was a chance, in spite of our watching the entrance to the harbor as a cat watches a mouse-hole, that the Spanish commander might, after all, slip out of his hiding-place and under cover of darkness or fog escape our guns.

Captain Sampson believed that he saw a way by which he could effectually cork the bottle and make Cervera's escape impossible. By permission of Captain Sampson, Lieutenant9 Hobson proceeded to carry out his daring scheme. With the help of seven sailors, who were eager to go with him at the risk of almost certain death, Hobson ran the coal ship Merrimac into the narrow channel, and by exploding torpedoes sank the vessel part way across it. Then he and his men jumped into the water to save themselves as best they could. It was one of the bravest deeds ever done in war and will never be forgotten. The Spaniards captured Hobson and his men, but they treated them well, and after a time sent all of them back to us in exchange for Spanish prisoners of war.

271. Fighting near Santiago; the “Rough Riders”; Cervera caught.— A few weeks later General Shafter landed a large number of American soldiers on the coast of Cuba near Santiago. The force included General Wheeler's cavalry, and among them were the “Rough Riders”. A good many of these “Rough Riders” had been Western “cowboys”; Colonel Roosevelt was one of their leaders, and on horseback or on foot they were a match for anything, whether man or beast.

The Americans at once set out to find the enemy. The Spaniards had hidden in the underbrush, where they could fire on us without being seen. They opened the battle, and as they used smokeless powder, it was difficult for our men to tell where the rifle balls came from or how to reply to them. But in the end, after pretty sharp fighting, we got possession of some high ground from which we could plainly see Santiago, where Cervera's fleet lay concealed behind the hills.

A week later our regular soldiers, with the “Rough Riders” and other volunteers, stormed up the steep heights,10 drove the Spaniards pellmell into Santiago, and forced them to take refuge behind the earthworks which protected the town.

Meanwhile Captain Sampson had gone to consult with General Shafter. While he was absent Commodore Schley and the other commanders of the fleet kept up a sharp lookout for Cervera, who was anxious to escape.

On Sunday morning, July 3 (1898), a great shout was sent up from the flagship Brooklyn, and another from Captain Evans's ship, the Iowa: “The Spaniards are coming out of the harbor!” It was true, for the sunken Merrimac had only half corked the bottle after all, and Cervera was making a dash out, hoping to reach the broad Atlantic before we could hit him.

Then all was excitement. “Open fire!” shouted Schley. We did open fire. The Spanish Admiral was a brave man; he did the best he could with his guns to answer us, but it was of no use, and in less than three hours all of the enemy's fleet were helpless, blazing wrecks. Cervera himself barely escaped with his life. He was rescued by the crew of the Gloucester; as he came on board that ship, Commander Wainwright said to him, “I congratulate you, sir, on having made a most gallant fight.” When not long afterward one of our cruisers11 reached Portsmouth, New Hampshire, with Cervera and more than seven hundred other prisoners of war taken in the battle, the people sent up cheer after cheer for the Spanish Admiral who had treated Lieutenant Hobson and his men so handsomely.

272. The end of the war; what the “Red Cross Society” did.— Soon after this crushing defeat the Spaniards surrendered Santiago. Next Porto Rico (Por′to Rēē′kō) surrendered to General Miles. By that time Spain had given up the struggle and begged for peace. An agreement for making a treaty of peace was signed at Washington (August 12, 1898). Our Government at once sent a despatch to our forces at the Philippines ordering them to stop fighting. Before the despatch could get there, Rear-Admiral Dewey and General Merritt had taken Manila.

The war was not without its bright side. That was the noble work done by the “American Red Cross Society” under Clara Barton. They labored on battlefields and in hospitals to help the wounded and the sick of both armies, and to sooth the last moments of the dying. Many a poor fellow who was called to lay down his life for the American cause, and many another who fell fighting for Spain, blessed the kind hands that did everything that human power could do to relieve their suffering. For the “Red Cross” helpers and nurses treated all alike. They did not ask under what flag a man served or what language he spoke—it was enough for them to known that he needed their aid. So, too, it is pleasant to find that the Spanish prisoners of war were so well treated by our people that when they sailed for Spain they hurrahed for America and the Americans with all their might.

While the war was going on we peacefully annexed the Republic of Hawaii (Hah-wy′ee), or the Sandwich Islands (July 7, 1898). Before the end of the contest with Spain our flag waved above those islands, as a sign that they had become part of the territory of the United States. Later, it floated, as a sign of conquest, over Porto Rico, Manila, the capital of the Philippines, and Guam (Gwam), the principal island of the Ladrones, in the Pacific. On New Year's Day, 1899, the Spanish colors were hauled down at Havana, and the stars and stripes took their place, as our sign of guardianship over Cuba.

Less than three years later (1901) the people of Cuba declared themselves independent. At the same time they voted to accept the friendly offer of the United States to continue to watch over life, liberty, and property in that island. In 1902 we withdrew the American flag and acknowledged the independence of the Republic of Cuba. (Provided Cuba fulfilled certain conditions.)

It will be remembered that Havana is the city in which Columbus was believed to be buried (see account of the burial of Columbus in Chapter 1). By order of the Queen of Spain, his remains were sent back after the war (December 12, 1898) to the city of Valladolid (Väl-yä-dō-leed′), his old home in Spain.12 To-day the Spaniards have nothing left on this side of the Atlantic which they can call their own—not even the corpse of the great navigator who discovered the New World, unless by chance his body still rests in the old church in San Domingo.

Many of our people wish to keep all of the islands we have conquered from Spain.13 They believe that by so doing we shall open new markets for our goods in the East, and in China; and that by having possessions in various parts of the globe we shall make the United States a great “world-power,”—the greatest, perhaps, that has ever existed in history.

Many other Americans, who are equally patriotic and equally proud of their country, believe that it would be a mistake for us to keep all of these islands. They say that distant possessions would make us weaker instead of stronger, that they would be likely to get us into quarrels with other nations, and that in the end we should have to spend enormous sums of the people's money in building more war-ships and fitting out new armies.

Time tests all things and all men. Time will not fail to show which of these two parties is right. That decision will add another chapter to the history of our country. Let us hope it will be a chapter that both you and I shall be glad to read.

273. The murder of President McKinley.— In the autumn of 1900 Major McKinley (see section 265) was re-elected President of the United States with Colonel Theodore Roosevelt (see section 271) as Vice President.

The next spring (1901) a grand exhibition, called the Pan-American Exposition,14 was opened at Buffalo, New York. In the autumn President McKinley attended a public reception at the Exposition. On this occasion (September 6) great numbers of people came forward to shake hands with him. Among these was a young man who was the son of emigrants that had come to the United States from Poland.15 At the moment the President was reaching out his hand to the young man the latter shot him twice with a revolver which he held concealed in a handkerchief. The President fell back fatally wounded and died about a week later (September 14). His last words to his friends were: “Good-bye, all; good-bye. It is God's way. His will be done.”

In accordance with law, Vice-President Roosevelt then became President. Five days later (September 19) the body of the dead President was laid in its last earthly resting-place at his late home in Canton, Ohio. President Roosevelt appointed that day for mourning and prayer. It was solemnly kept, not only by all the people of the United States, but by great numbers of the people of Europe, who joined with us in our sorrow.

In London, in Paris, in Berlin, in Edinburgh, and other European cities, the American flag was displayed draped in black, and funeral services were held in Westminster Abbey and other churches. Throughout America a great silence fell upon the people when the body of the murdered President was laid in the grave. In New York, and in many other of our chief cities, cars and steamboats ceased to run for a time; the ever-busy telegraph ceased to click its messages, and thousands of people stood reverently in the streets as if they felt that they were present at the burial-ground in Ohio. It was an occasion that no one who took part in it will ever forget.

274. The unfinished pyramid; making history.— On one of the two great seals of the United States a pyramid is represented partly finished. That pyramid stands for our country. It shows how much has been done and how much still remains to be done. The men whose lives we have read in this little book were all builders. By patient and determined labor they added stone to stone, and so the good work grew. Now they have gone; and it is for us to do our part and make sure that the pyramid, as it rises, shall continue to stand square, and strong, and true.

What is said about the North and the South since the war? Tell about the growth of the South. What is said about the West? What is said about railroads? What is said about people going west?

How long is it since Columbus discovered America? What is said about the celebration of that discovery? What is said about the possessions which Spain once had in North America? What is said of the rebellion in Cuba? What is said about the destruction of the Maine? What did the United States do? Give an account of Commodore Dewey's victory. What is said of Cervera's fleet? What did Hobson do? What is said about the fighting near Santiago? Who were the "Rough Riders"? What happened to Cervera's fleet? When did the end of the war come? What is said of the "Red Cross"? What is said of Hawaii? Over what islands does our flag now wave? What is said about the remains of Columbus? What do people think in regard to keeping all of the islands now under our control? What terrible event occurred at Buffalo in the autumn of 1901? What is said about one of the great seals of the United States? What does the unfinished pyramid stand for? What does it show us? What is said of the men whose lives we have read in this book? Is there anything left for us to do?

Footnotes[edit]

1 Prospered: to prosper is to succeed, to get on in life, to grow rich.

2 Ranches (ran′chez): farms at the West for raising horses and cattle, or sheep.

3 In all, the war lasted from April 21, 1898, to August 12, 1898, but Congress did not formally declare war until April 25. The fighting covered one hundred and seven days—namely from May 1 to August 15.

4 Mine: here this word means a quantity of powder or some other explosive substance placed under water for the purpose of blowing up a vessel. See account of Fulton's torpedo in Chapter 21.

5 See section 272 on the vote of the Cuban people in 1901 accepting the guardianship and protection of the United States.

{{sup| Captain William T. Sampson, who was then Acting Rear-Admiral, has since been promoted to the full rank of Rear-Admiral, and so, too, has Commodore Winfield Scott Shley.

{{sup| Philippine Islands, or the Philippines (Fil′ip-peens); see the Map of the World.

8 Commodore George Dewey—now Admiral Dewey.

9 Lieutenant (Loo-ten′ant), an officer in the navy below the rank of captain.

10 Of El Caney and San Juan (San Wahn), suburbs of Santiago. The battles of El Caney and San Juan were fought mainly by the “regulars”—that is, by the soldiers of the regular standing army of the United States. Volunteers are men who enlist to fight in a war but do not belong to the regular standing or permanent army of the country.

11 Cruisers (krew′zers), vessels of war.

12 Columbus spent the last years of his life there. But it is said that the remains of Columbus were not actually carried to Valladolid, but were deposited in the Cathedral at Seville in Spain.

13 We paid Spain $20,000,000 for the Philippines.

14 Pan-American Exposition, that is, the exhibition of all the nations of North, South, and Central America.

15 The name of the young man was Leon F. Czolgosz (Chol′gosh). He declared himself an Anarchist, that is, one who wishes to overthrow all government. He was executed at Auburn, New York, October 29, 1901. President McKinley is the third President who has been murdered; President Lincoln, shot by Booth in 1865, and President Garfield, killed by Guiteau (Ḡē-toe′) in 1881, being the first two.