The Boy Travellers in Australasia/Chapter 12

CHAPTER XII.

THE provincial district of Canterbury is both an agricultural and a pastoral country, part of it being well adapted to grain-growing, and the rest to grazing. Its staple productions are grain and wool, and

UNDER THE SHEARS.it ships large quantities of both to England and other countries. There are more than 5,000,000 sheep in the district, besides 200,000 cattle and horses; the annual product of wheat is nearly 7,000,000 bushels, and of oats half that amount. Evidently the Canterbury pilgrims did not choose unwisely when they came here to found their Utopia.

A SHEEP-SHEARING SHED IN NEW ZEALAND.

The party was ready at the time appointed; in fact, it was ready some minutes before the time, in accordance with the promptness which characterized the movements of Doctor Bronson and his nephews. They found the railway-station large and commodious, and arranged after the plan of an English station in a community of much greater extent. "It was built for our future rather than for our present needs," said Mr. Abbott. "In time we hope to require all the space at our command, but just at present there is sometimes a suggestion of loneliness about it."

The country through which the train passed on its way to Springfield bore evidences of careful cultivation, and our friends found it difficult to believe that previous to 1850 this whole region was a wilderness. Certainly the Canterbury pilgrims were not inclined to idleness, and the condition of their fields indicated that they belonged to men of industry and intelligence. As the train moved westward the mountains became more and more distinct, and long before Springfield was reached they filled the whole of the western horizon with their towering peaks.

"We have an agricultural college at Lincoln," said Mr. Abbott, "where our young men can learn practical and scientific agriculture adapted to the colony. It is under the control of the Canterbury College Board of Governors, and has a farm of five hundred acres, and comfortable buildings for the students. Agriculture is taught practically, and we have every reason to expect excellent results from the college in the course of the next few years."

From Springfield a ride of a few hours carried the party to the sheep-station, where they were warmly welcomed. The sun was just setting when they arrived, and it was too late to examine the place and its surroundings. A supper consisting of mutton in cutlets and stew, accompanied by bread baked on hot stones, and washed down with tea, received careful and appreciative attention by the hungry travellers. The sleeping accommodations were limited but comfortable, and in the morning all were out in good season, and ready to consider the sheep-raising question.

Horses were brought, and though somewhat unruly at first, they proved very satisfactory to their riders; at any rate, nobody had any bones broken in the forenoon's ride, though there were some narrow escapes. Accompanied by their host, the party rode over the sheep-run for several miles, visiting the herders in charge of their flocks, and studying the peculiarities of the country. Frequently during their ride Mr. Abbott drew rein and called attention to the natural and other advantages or disadvantages of the business, and showed them wherein it differed from sheep-farming in America.

A FLOCK OF SHEEP AMONG THE HILLS.

"Here, as everywhere else," said he, "we must make sure of a plentiful supply of water if we want to prosper. Some of the streams run dry at certain seasons of the year, and it is necessary that a man should know before he locates if a stream can be relied upon throughout the year. On some of our runs we have made trenches and brought water for long distances, as it is cheaper to have the water run where we want it than to drive the sheep several miles. There is an abundance of water flowing from the mountains, but it is not properly distributed by nature; therefore we have called science to our aid, and extensive irrigation-works have been made by the local and colonial governments, and in this way thousands upon thousands of sheep-pasturing and agricultural lands that were formerly almost worthless are now valuable. You probably observed some of the irrigating-ditches as we were coming along the railway.

"In the lower hills we do not suffer from snow-storms, but some of the sheep-farmers who have established themselves high up among the mountains have lost heavily from this cause. Sometimes there will be several years without a severe storm, and then will come one that kills off thousands and thousands of sheep in a very few days. This was the case a few years ago, when the losses were very heavy; one flock of more than a thousand sheep was shut up in the mountains, and perished with their herder, who was found dead by their side. Other flocks were buried and died in the snow, but the herders managed to save themselves.

"But the rabbits and parrots are our worst enemies, as you may have heard."

"Yes, I've heard so," replied Frank; "at least I've been told that the rabbits have been terribly destructive of grass, and ruined many thousand acres of pasturage."

"Rabbits were first introduced," said Mr. Abbott, "as a table luxury and to furnish hunting sport; and besides, it was thought they would be handsome ornaments on a place. But very soon it was found that they were a great pest; they increase very rapidly, and as the country was sparsely settled, the settlers were unable to keep them down. Men were hired to trap, shoot, or capture them in some way, and were paid at the rate of twopence for each rabbit-skin; but this plan was not effective, as it was not rapid enough, and after many experiments we took to poisoning the creatures by wholesale."

"How did you do it?"

"By means of grain saturated with phosphorus; we prepare barrels with closely fitting lids, and fill them half full with oats; then we pour boiling water on the oats, and when they are thoroughly soaked and swollen we pour in a quantity of phosphorus, quickly replacing the cover, so that the poisonous fumes cannot escape. This grain scattered over the ground is death to the rabbits, but the disadvantages of the plan are that sheep are often killed by the poisoned grain.

SHEEP AND HERDER KILLED IN A SNOW-STORM.

REDUCING THE RABBIT POPULATION.

"Australia and Tasmania are equally afflicted by rabbits," the gentleman continued, "which were introduced into those countries from New Zealand for the same reasons that they were introduced here. Millions of pounds sterling would not compensate for their ravages, and the public and private expenditure for their destruction has already mounted into those figures. Dogs, ferrets, poison, trapping, drowning, and every other known means have been tried to reduce them, but without success. Occasionally the whole population turns out for a rabbit 'battue,' in which many thousands of the animals are killed. The owners of sheep and cattle runs have built hundreds of miles of rabbit-fences, and the colonial governments have done likewise; the fences stop the progress of the vermin for a time, but after a while they manage to burrow beneath them and come up on the other side, and so the fences are not effective to prevent the spread of the pest."

"Haven't I read about their being killed by forcing noxious gases into their warrens?" one of the boys asked.

"Yes," was the reply, "that has been done, but the machines for making and using the gas are costly and cumbersome, and in rocky regions they do not work satisfactorily.

"Recently the Government of New South Wales has offered a reward of twenty-five thousand pounds to any one who will devise a successful system of destroying rabbits, provided it is not dangerous to live-stock and to human beings. The attention of the scientific world is directed to the subject, and perhaps the remedy may be found. Pasteur, the celebrated French scientist, has proposed to inoculate a few rabbits with chicken-cholera and allow them to run among their kindred, and thus introduce the disease. He says it is harmless to all animals, with the exception of rabbits and chickens, and believes that the whole rabbit population could in this way be killed off, though at the same time our domestic fowls would be killed too, unless they were carefully shut up. We could afford to lose every fowl in the southern hemisphere if we could only get rid of this great pest of rabbits; but it will be necessary to proceed very cautiously, lest our sheep and cattle should suffer."

The youths had a realizing sense of the extent of this pest in the Australasian colonies, when they saw on several occasions whole hillsides and stretches of plain that seemed to be in motion, so thickly was the ground covered with rabbits. Mr. Abbott further told them that Dunedin and other cities had a regular exchange, or market, for rabbit-skins, where dealings were conducted as in the grain, wool, and other exchanges. The skins mostly find their way to London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and Naples, where they are made into "kid" gloves of the lower grades. They are also made into hats, and it is hoped that they may be found useful for other purposes, so as to make profitable the wholesale slaughter of the animals on whose backs they grow.[1]

"How about the parrots?" Fred asked, when the rabbit question was disposed of.

"That is a strange piece of history," replied Mr. Abbott. "When the sheep-farmers first established their stations among the mountains there were flocks of the kea, or green parrot, living in the glens and feeding entirely on fruit and leaves. They were beautiful birds, and nobody suspected any harm from them.

"After a time it was observed that many of the sheep, and they were invariably the finest and fattest of the flocks, had sores on their backs, and always in the same place, just over the kidneys. Some of the sores were so slight that the animals recovered, but the most of them died or had to be killed to end their sufferings.

"The cause of these sores was for some time a mystery, but at length a herdsman on one of the high ranges declared his belief that the green parrots were the murderers of the sheep. He was ridiculed and laughed at, but was soon proved to be right, as a parrot was seen perched on the back of a fat sheep and tearing away the flesh.

"Investigation showed that in the severe winters the parrots had come at night to the gallows, where the herdsmen hung the carcasses of slaughtered sheep. They picked off the fat from the mutton, and showed a partiality for that around the kidneys; how they ever connected the carcasses with the living sheep is a subject for the naturalists to puzzle over, and especially how they knew the exact location of the spot where the choicest fat was found in the living animal. It seems that the attacks on the sheep began within a few months after the parrots had first tasted mutton at the meat-gallows."

"Have they done much damage?" one of the youths asked.

"Yes, a great deal," was the reply; "but not so much of late years, as they are being exterminated. One man lost nineteen fine imported sheep out of a flock of twenty, killed by the parrots; and another lost in the same way two hundred in a flock of three hundred. Every flock in the mountains suffers some from this cause, probably not less than two per cent.

"A shilling a head is now paid for keas, and there is a class of men who hunt them for the sake of the reward; but the sagacious birds PARROTS.

Frank and Fred asked about the profits of the sheep-raising business, but the information they obtained did not encourage them to become sheep-farmers in New Zealand. What with the rabbits and the parrots, with diseases among sheep, fluctuations in wool, the high price of labor, especially at shearing-time, when extra men must be engaged, with a full knowledge of their importance, the profits are not what they were in the early days of the industry.

From the sheep-station they returned to Springfield, and took train again in the direction of Christchurch. At the second or third station from Springfield they were met by a carriage, which took them to the wheat-farm, which was one of the objects of the journey. Time did not permit a lengthened stay here, but it was sufficient to enable them to see a good deal before their departure.

Here is a summary of what they learned about wheat-farming in New Zealand:

"About four hundred thousand acres of ground are utilized for wheat in the different counties of the colony. The farmers expect twenty-five

A NEW ZEALAND PEST.bushels to the acre in most localities, but frequently this figure is exceeded, the average throughout the country for one year being in excess of twenty-six bushels. Consequently, the wheat crop may be set down at ten million bushels, of which by far the greater portion is available for exportation."

Frank made a note here to the effect that half a million acres of land were devoted to raising oats, at an average of thirty-five bushels to the acre. Barley, hay, potatoes, and other things brought the amount of land under crop up to a million and a half acres, while there were five and a half million acres under grasses, including grass-sown land that had not been previously ploughed. The figures were about evenly divided between the two islands. The colony contains about fourteen million sheep, seven hundred thousand cattle, and one hundred and sixty thousand horses.

"Of late years the export of wheat has fallen off, owing to the competition of India and America in the markets of Europe; the wheat-farms of New Zealand are so unprofitable that the owners talk of putting much of their ground into grass, though they will continue the cultivation in order to supply enough for home consumption and to employ the machinery they have on hand.

A STEAM THRESHING MACHINE.

"The open country of South Island is admirably adapted for wheat, and the soil is so easy to manipulate that double-furrow ploughs are used. The large farms are provided with all the latest improvements in machinery and implements; and we found the intelligent farmers thoroughly familiar with American reapers and mowers, steam threshing-machines, steam wagons, and other things, so that we felt quite at home. They asked us about the wheat-farms of America, and were inclined to shake their heads when we told them of fields so large that a plough could only turn a single furrow around one of them in a day's time.

"'Do you really mean it?"' said one of them, with an emphasis of surprise.

"Doctor Bronson assured them of the correctness of the statement, and added that on the Dalrymple farm in Dakota, or rather on one of the Dalrymple farms, there was a single field of thirteen thousand acres. 'That makes,' said he, 'about twenty square miles, and I doubt if you have any team that could plough more than one furrow around such a field in a day.'

"They acknowledged that such was the case, and though they had fields containing hundreds of acres inside a single fence, they had nothing that approached the wheat-fields of Dakota. We were sorry afterwards that we mentioned our enormous wheat-fields, as we thought it set them to thinking of American competition, and the effect it might have on their own business in future; but of course we couldn't resist our national tendency to 'brag' a little.

"Afterwards, when we were visiting a dairy-farm, a matter-of-fact Scotchman who owned the place remarked that he presumed we had much larger dairy-farms in America, as he had heard of one where they had a saw-mill which was propelled by the whey that ran from the cheese-presses, and also a grist-mill operated by buttermilk!

"In the wheat-growing belt of South Island there is a scarcity of timber, the forests being mainly in the hilly and mountain region. The scarcity of timber has led to the planting of forests. Considerable attention is given to this both by the authorities and by individuals, and good results are predicted at no distant day. There is also a scarcity of water, and to meet it irrigation-works have been constructed, as already stated.

"Wheat-farmers are troubled by rabbits, and also by sparrows, which were introduced to kill off caterpillars and other insect pests. The sparrows increased in numbers almost as rapidly as the rabbits; they changed their habits, and from carnivorous taste turned to eating fruits and grains. The New Zealand sparrow shuns the caterpillars and worms he was imported to devour, and feeds on the products of the garden and the field. The same is the case in Australia, where the sparrows are now in countless millions, the descendants of fifty birds that were imported about 1860. The colonial governments have offered rewards for the heads and eggs of the sparrows, and though this has caused an extensive destruction it has not perceptibly diminished their numbers.

ENGLISH SPARROWS AT HOME."In an official investigation of the 'sparrow pest,' one man testified that he sowed his peas three times, and each time the sparrows devoured them. Another told how the birds destroyed a ton and a half of grapes, in fact cleared his vineyard, and others said they had been robbed of all the fruit in their gardens."

This is a good place to say something about the exotics that have been introduced into the Australasian colonies. Cattle, horses, sheep, and swine have been of unequivocal benefit, and so has been the stocking of the rivers with trout, carp, and other food fishes of Europe. Larks and a few other song-birds have thus far proved of no trouble, but even they may yet give cause to regret their introduction. In addition to the animal pests already mentioned, the Indian mina, or minobird, a member of the starling family, has become a great nuisance, almost equal to the sparrow.

We will now turn from the animal to the vegetable exotics.

Wheat, oats, and the other grains are of course in the same beneficial category as the domestic animals. The innocent water-cress, which is such a welcome addition to the breakfast and dinner table, has grown with such luxuriance as to choke the rivers, impede the navigation of those formerly navigable, and cause disastrous floods which have resulted in loss of life and immense destruction of property. In the Otago and Canterbury districts of New Zealand, the Government makes a large expenditure every year to check the growth of this vegetable pest.

The daisy was introduced to give the British settler a reminder of home, and already it has become so wide-spread as to root out valuable grasses. Years ago an enthusiastic Scotchman brought a thistle to Melbourne, and half the Scotchmen in the colony went there to see it. A grand dinner was given in honor of this thistle, and on the following day it was planted with much ceremony in the Public Garden of Melbourne. From that thistle and its immediate descendants the down was carried by the winds all over Victoria, and many thousands of acres of once excellent fields are now covered with tall purple thistles to the exclusion of everything else. Large amounts of money have been expended in the effort to eradicate the thistle, but all in vain.

The common sweetbrier is another vegetable exotic that has become a pest. It was introduced for the sake of its perfume, but has become strong and tenacious, spreading with great rapidity, and forming a dense scrub that utterly ruins pasture-lands. Money has been expended for its destruction, but it refuses to be destroyed.

The English sparrow is the subject of much discussion in the United States, and the opinion seems to be gaining ground that he is a pest to be put out of the way if possible. Those who are inclined to advocate his continued presence under the Stars and Stripes would do well to study his history in the Australasian colonies, where the damage he has caused is practically incalculable.

Our friends returned to Christchurch, and after another day in that city proceeded by railway in the direction of the South Pole. At the earnest solicitation of one of their acquaintances, they stopped a few hours at Burnham, eighteen miles from Christchurch and on the line of railway, to visit the industrial school for children whose parents have neglected to care for them properly. The object is to instruct the children in useful trades and occupations which can afford them an honorable support in later years. The school has extensive buildings and grounds, and has constantly about three hundred children under instruction. Nearly all the ordinary trades are taught there, and the manager said the children generally showed great proficiency in learning what was set for them to do.

"The main line of railway to Dunedin," wrote Frank in his journal, "has several branches which serve as feeders by developing the country through which they pass. Portions of the line are through rolling or hilly country, and there are other portions which stretch across plains resembling the prairies of the western United States. On the western horizon rises the line of snow-clad mountains, again reminding us of railway travelling over our own plains as we approach the range of 'The Rockies.'

"We crossed several fine bridges spanning the rivers Rakaia, Ashburton, Rangitoto, and Waitaki; these rivers flow through wide beds, and though ordinarily of no great volume become tremendous torrents in seasons of floods. In the early days many a traveller came to his death while seeking to ford one of these treacherous streams, and many sad memories are connected with their history.

CLASS IN THE INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL.

"As we approached Timaru, one hundred miles from Christchurch, Mount Cook, the highest mountain of New Zealand, was pointed out to us. It is 12,349 feet high, and its top is covered with perpetual snow; it is the highest peak of the Southern Alps, which stretch along the west coast of New Zealand for nearly two hundred miles, very much as the Andes lie along the west coast of South America. Fred and I thought we would like to climb Mount Cook, and spoke to Doctor Bronson about it. The Doctor dampened our enthusiasm by saying that it was more difficult of ascent than Mont Blanc, and he was unaware that the feat had been accomplished since Rev. W. S. Green and two Swiss companions reached the top of the mountain in 1883.

"He added that Mr. Green was a member of the famous Alpine

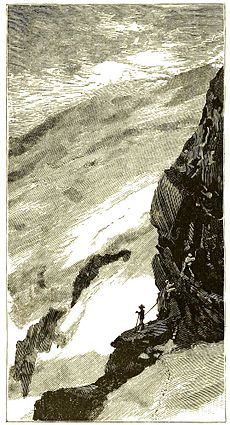

A PERILOUS NIGHT-WATCH.

"They had all the variety of adventures recorded in the history of Alpine climbing," said a gentleman who was in conversation with Doctor Bronson at the time the query was propounded, "except that of being swept into crevasses or down the slope of the mountain and losing their lives. Mr. Green has published a book, entitled 'The High Alps of New Zealand,' in which you will find a description of the ascent of Mount Cook. After you have read it I don't think you'll want to follow the example of that gentleman, unless you have more than the ordinary enthusiasm about mountain-climbing."

"As we looked at the peak of Mount Cook rising sharply into the sky," Frank continued, "we concluded that a view of the mountain from below would satisfy all our desires. The gentleman roused our curiosity, however, when he told us about the wonderful glaciers that lie on the lower slopes of the great mountain, some of them larger than any of the glaciers of Switzerland. Then on the way he pointed out several lakes that are fed by the glaciers on Mount Cook and other peaks of the Southern Alps just as the lakes of Switzerland and Italy are fed by the glaciers from the Alps of Europe. Some of these lakes are forty or fifty miles long, and of almost unknown depth; indeed, some of them are deeper than the level of the ocean, though their bottoms have been filling up for ages with the débris brought down by the glaciers.

"Look on the map and find Lake Tekapo; it is fifteen miles long and three wide, and is supplied by the great Godley glacier, which lies just above it. The Tasman glacier, eighteen miles long, is the largest in New Zealand, though this statement is disputed by some authorities. At any rate, there are a great many glaciers, and all have not been fully explored. They are on the western as well as on the eastern slope of the mountains; one of them descends from Mount Cook to within seven hundred feet of the sea-level, and for a long distance is bordered by magnificent vegetation in which tree-ferns and fuchsias are conspicuous. In this respect the glacier resembles that of Grisons, in Switzerland, which comes down far below the snow-level, and is bordered with pine forests and almost by cornfields.

THE SUMMIT OF MOUNT COOK.

"Some of the moraines, or channels, cut by the glaciers are very deep, and most of the lakes lie in what were moraines ages and ages ago, when the ice extended much farther than it does now. Lake Pukaki is a fine example of this; it is shut in by an old terminal moraine which attains a height of one hundred and eighty-six feet above the surface of the lake. On the western side of the Alps there are deep channels which are called 'sounds,' and greatly resemble the fiords of Norway. Some of them are eighteen or twenty miles long, and vary from half a mile to two or three miles in width; their sides rise almost perpendicularly, sometimes for hundreds of feet, and they are nearly all too deep to permit ships to anchor. Sounding-lines a thousand feet

ATTEMPT TO CLIMB THE EASTERN SPUR.long often fail to find bottom there. Perhaps they are called sounds because they can't be sounded.

"These sounds are supposed to be ancient moraines, and during the ice period of the world they were the beds of glaciers coming from immense lakes, encircling the bases of the mountains and covering areas of thousands of miles. Altogether the scenery of the Southern Alps is said to be magnificent."

Doctor Bronson had decided to make no stop on the way until reaching Dunedin, and though earnestly urged to spend a day at Timaru, in order to see the harbor works there, the establishment for freezing meat, the barbed wire factory, and other enterprises, he did not swerve from his resolution. The party reached Dunedin late in the evening, and went to the hotel which had been recommended as one of the best. They had no occasion to complain of it, and in the morning were ready to "do" the sights of the place.

Dunedin has the reputation of being the largest, best built, and most important commercial city of New Zealand; it is the capital of the provincial district of Otago, and the commercial centre of a large area of country. The settlement of Otago was projected in 1846, and it was intended to be exclusively occupied by adherents of the Free Kirk of Scotland, just as Canterbury at a later date was to be the monopoly of adherents of the Church of England. The colony was not especially prosperous under its exclusive system, though the thrifty settlers had not much to complain of except the scarcity of neighbors.

But gold changed the whole scene, and broke down the barrier which the projectors of the colony had erected. In 1861 rich gold-diggings were discovered about seventy miles from Dunedin; diggers flocked in from Australia and from other parts of the world, and from the beginning of the gold rush Dunedin dates its prosperity.

RIVER ISSUING FROM A GLACIER.

It has all the characteristics of a thriving city; gas, paved streets, horse-railways, race-course, theatres, schools, academies, churches, colleges, parks, gardens, museum, manufactories, and numerous other urban things and institutions, all are to be found here. There are three daily papers published in Dunedin, and a score of weeklies and monthlies, and there is an excellent library, supported partly by the municipal authorities, and partly by contributions of enterprising citizens. With its immediate suburbs it has a population of fifty thousand, and is steadily increasing year by year. Its Scotch origin is apparent in the faces and accent of the great majority of the residents, and by the statue of the Scottish poet. Burns, which stands protected by a railing in front of the town-hall. Most of the streets are named after those of Edinburgh and Glasgow.

HYDRAULIC MINING.

"I wanted," said Frank, "to make a note of the things they manufacture in Otago, and especially at Dunedin, but the list was so long and time so scarce that I didn't try; but I'll remark particularly that they manufacture a good deal of woollen cloth, leather, cotton, and other fabrics, which is something very unusual for so young a colony. There is more manufacturing here than in any other part of New Zealand, and the Scotch settlers of Otago seem to have brought here the thrift and industry for which their native land is celebrated."

Doctor Bronson asked Fred if he had learned anything about the product of gold in Otago.

"I have the figures right here," was the reply. "From 1861, when the first discoveries were made, down to the end of March, 1884, the Otago gold-fields produced 4,319,544 ounces, which were valued at £17,026,320, or about $85,000,000. Most of the gold has been obtained from alluvial washings of various kinds, such as sluicing, tunnelling, and hydraulic washing; auriferous reefs have been successfully worked in several instances, and unsuccessfully in more. Gold-mining has become a regular industry of the country, and is less subject to fluctuations than in former times. Once in a while a new field is opened, and there is a rush to work it; but the excitement over such discoveries is not like that of the five or ten years following 1861.

A SQUATTER'S HOME

From Dunedin our friends proceeded by rail again to Invercargill, 139 miles from Dunedin, or 369 from Christchurch. Invercargill is a

A MOUNTAIN WATER-FALLprosperous town of some eight or ten thousand inhabitants, and is near the southern end of South Island, a sort of jumping-off place, as Frank called it while looking at its location on the map. The real terminus of the island, though not its most southerly point, is The Bluffs, about seventeen miles below Invercargill, which stands on an estuary called New River Harbor.

The morning after their arrival the travelling trio took the train for Kingston, eighty-seven miles, at the southern end of Lake Wakatipu. The train carried them through a fine country of broad plains dotted here and there with tracts of forest. The region appeared to be well settled, as there were little villages scattered at irregular intervals, fields and pastures surrounded by fences, herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, isolated farms, saw-mills, and other evidences of settlement and prosperity. Several branch railways diverge from the main line and open up agricultural, pastoral, mining, lumber, and other districts of much present or prospective value.

"As we approached the lake," said Frank in his journal, "the country became more mountainous and picturesque. The train wound through a long defile, and then came out upon the 'Five Rivers Plains,' which take their name from five streams of water that pass through them. We passed through the Dome Gorge, and at Athol, sixty-nine miles from Invercargill, the conductor told us we were in the lake country. The hills and mountains were everywhere about us, and in the west the great range of the Alps rose into the sky. At Kingston the railway ends, and we stepped on board the steamboat, which carried us the whole length of the lake. The lake is sixty miles long, and reminded us of Lake Lucerne in Switzerland.

"We spent the night at Queenstown, a mining and agricultural town about twenty miles from Kingston, and on the next day completed our journey to the head of the lake. The scenery is magnificent, and I can no more describe it adequately in words than I can tell how a nightingale sings or a mangosteen tastes. All around us are the mountains, the highest peaks covered with perpetual snow that seems to flash back the rays of the sun, before whose heat it refuses to melt. In the distance, higher than all the rest, is Mount Earnslaw; we saw it clearly defined against the sky, but it is very often veiled by the fleecy clouds that sweep around it.

SHOTOVER GORGE BRIDGE.

"We were urged to stop at Queenstown and see the mining operations in the neighborhood, but time did not permit us to do so, and we returned to Invercargill as quickly as the railway and steamboat could carry us. Queenstown is one of the mining centres of the Otago goldfields, which we have already mentioned, and has had the usual ups and downs of mining life. The Otago mines cover a wide extent of country, and as much of the region in which they lie is agricultural, living is cheaper here than in most other mining regions.

"A good many Chinese are engaged in mining in the New Zealand gold-fields, and we were told that in one place—Orepuki—there was a mining population of four hundred Chinese that subscribed £100 ($500) towards building a Presbyterian church, the total cost being less than a thousand dollars. And yet I presume there are white men in Orepuki who would call one of their Mongolian neighbors a 'heathen Chinee!' Near Dunedin and other places, as well as in the neighborhood of most of the Australian cities, the market-gardening is largely managed by the Chinese. They seem to have almost a monopoly of this business, and we were told that no European could successfully compete with them when they went at it in earnest."

ON THE SHORE OF THE LAKE.

- ↑ A recent writer on this subject says: "On the arid, barren Riverina plains (whereon naturally not even a mouse could exist) there are pastured at present some twenty or twenty-five millions of high-class merino sheep. These sheep are being gradually eaten out by rabbits. The following will serve as an illustration, and it must be borne in mind that it is only one of many which could be adduced.

"On the south bank of the river Murray, consequently in the colony of Victoria, there is a station named Kulkyne, which has about twenty miles frontage to that river. The holding extends far back into arid, naturally worthless, waterless country. On that station, by skilful management and by command of capital, there came to be pastured on it about 110,000 sheep. When I two or three years ago visited that station I found that the stock depasturing it had shrunk to 1,200 sheep dying in the paddock at the homestead; 110,000 sheep to 1,200 sheep!

"The rabbits had to account for the deficiency. On that station they had eaten up and destroyed all the grass and herbage; they had barked all the edible shrubs and bushes, and had latterly themselves begun to perish in thousands."