The passing of Korea/Chapter 25

CHAPTER XXV

ART

It cannot be said that the Korean is lacking in the aesthetic instinct, but its development has been narrow. There has been no scientific development in their art, no formulation of aesthetic laws, no intermixture of a rational or regulative method. The statement that there is a pronounced arithmetical element in music, that geometry is essential to successful landscape gardening or that a knowledge of conic sections is essential to bridgebuilding, would arouse only mirth in the Korean. But it is nevertheless true that the lack of the mathematical element has deprived all Asia of genuine martial music.

A Korean house is a good illustration of the statement that bijouterie is the prevailing aim of their art. However large the house may be or however spacious the site, the place is divided by a network of walls into a vast number of alleys and courtyards, each very pretty in its way, but destroying all possibility of effective combination. The whole space is frittered away in a labyrinth of cheerless walls, which to the Westerner are more suggestive of a prison than a residence. Now the Korean delights in this bee-hive sort of existence. Each suite of rooms has its special charm to him. In one of them he keeps, perhaps, a beautifully embroidered screen, in another an ancient vase which is a family heirloom, and in another a rare potted palm or cactus; but he would never think of exhibiting all these things in combination.

One advantage that arises from their one-thing-at-a-time form of aesthetic development is that it can be shared more equally by high and low alike. If a single flowering plant can give as much pleasure as a whole gardenful, the poor man is much nearer his wealthy neighbour in his opportunities for aesthetic pleasure than is the case in Western countries.

This method has its advantages. It tends to a concentration of attention and a consequent exactness in detail which are not generally found in connection with a broader form of art. His embroidered butterfly will be worked out to a painful point of exactness, while the perspective of the whole scene may be ludicrously wrong. The Korean almost invariably makes the farther edge of the table longer on his canvas than the nearer edge, and I once saw a magnificently embroidered stork standing on one leg, while the other leg, which was held up gracefully, passed behind a tree that stood at least ten feet beyond the bird. It may be that the Korean has always been so closely shut up by walls that he has never so much as imagined such a thing as a " vanishing point."

I am not sure but it is this love of detail that has led to the introduction of the grotesque and monstrous into the art of the whole East; a sort of protest against their limitations. The aesthetic nature having been confined so long in narrow channels was forced to find a vent for itself in some way, and did so by a violent rupture into the realm of the fantastic. So we find in every picture some dwarfed tree or curiously water-worn rock, some malformation that excites the curiosity. No picture of an ancient warrior is correct unless he has warts as big as walnuts all over his face, and eyebrows that rival his beard in length.

As to colour in art, the Koreans are still as primitive as in ancient days. Their red is the red of blood or of the peppers that lie ripening on their roofs. Their green is the vivid green of the new-sprouting rice or the dark blue-green of the pinetree. Nature's colours are in their art as nature's sounds are in their wonderfully mimetic language.

As to form in art, the Korean is strictly a realist, except in so far as he has impinged upon the realm of the fantastic. There are no idealised expressions in his art, no winged cherubs, no personification of any power of nature, no Cupid with his bow and arrows; and it is just because of this lack of imaginative power that such a thing as aesthetic combination is unthought of. Imagination is the power of arranging and rearranging one's mental furniture in such a way as to produce new and pleasing, or useful, combinations; and if a man has not this power, the arrangement of his house furniture, the colours on his canvas, the notes of his music and the flowers of his garden must all suffer. It is this lack which has made Korean history

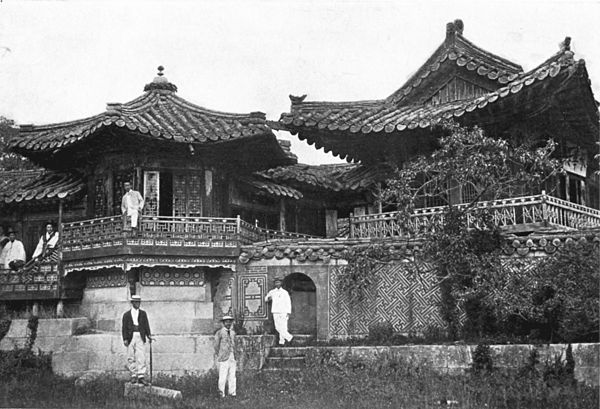

MURAL DECORATIONS IN OLD PALACE

But some may say that the common belief in evil spirits and the genii of mountain, tree and stream implies a high degree of imaginative power. Not so; this is nothing but instinct, the natural working of the law of self-preservation. You might as well say that the porcupine has imagination because he rolls up into a ball and presents the thorny side of life to the approaching enemy. The crudest method of explaining obscure phenomena is the attributing of them to the agency of demons, genii and spirits. So far from being evidence of an imaginative nature, this demon worship argues the very opposite. He fails to see things in their proper relations, and he remains oblivious of the fact that, running through these phenomena, there is a oneness of plan and an adaptation of means to ends which precludes the possibility of his horde of spirits. It is moral instinct which has led him to reason out some personal agency in the conduct of human affairs. In other words, it is conscience, which, from the pagan point of view, does " make cowards of us all." The consciousness of personal demerit makes the Korean picture his spirits and goblins as inimical to man, and produces that servility, as distinguished from humility, which is indelibly stamped upon all pagan worship.

But we must hasten to enumerate briefly some of the most conspicuous forms of Korean art. We have already mentioned music. Architecture has never been looked upon here as a fine art. It is entirely utilitarian, except in the case of royal palaces and temples, and even here art is exhibited almost exclusively in the decorations. These and other architectural decorations may be passed by with brief mention, for they are anything but artistic to the Western eye. In mural decoration they have produced some pleasing effects, but they are very crude and will not bear comparison with what goes under that name in our own lands. Embroidery upon silk is considered by Koreans to be one of their finest achievements in the line of art. Some of it is fairly well executed, but the very best will not begin to compare with even ' the medium grades in China or Japan. Painting sketches of branches of trees, sprays of flowers, bunches of grass, and old stumps and rocks with a brush pen and India ink is a favourite form of artistic work, and here we find regularly formulated laws. Each blade of grass must droop in accordance with a fixed law, and each flower must stand at just the right angle from the stem. After many years of familiarity with these things, even the Westerner finds a certain amount of interest in these pictures, and while they would be called the veriest daubs by the uninitiated, we must confess that they make a certain approximation to what we might call real art. It is a question, however, whether it is worth the time it takes to learn to appreciate it.

In the line of ceramics Korea has nothing to show. Long centuries ago she may have had some slight claims to consideration along this line, but there are very few evidences of it to-day. It is common for travellers to buy small iron boxes ornamented with inlaid silver or nickel. The work is crude, but the Greek key pattern which is usually followed redeems them from utter contempt. Some of the silver filigree work that is done, especially in the far northeast, is worthy of mention, but the artisans have only a few set designs, and these they follow so slavishly as to suggest the idea that they are heirlooms. Inlaying mother-o'-pearl in a kind of lacquer upon boxes, chests, and cabinets has a pleasing effect, but the inartistic forms of the objects thus decorated detract much from the general result. In this also the key pattern is most prominent.