Weird Tales/Volume 36/Issue 2/The Liers in Wait

| The | Liers in Wait |

By Manly Wade Wellman

Here lies our Sovereign Lord the King,

Whose word no man relies on,

Who never said a foolish thing.

Nor ever did a wise one.

—Proffered Epitaph on Charles II

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

Yes, Jack Wilmot wrote so concerning me, and rallied me, saying these lines he would cut upon my monument; and now he is dead at thirty-three, while I live at fifty, none so merry a monarch as folks deem me. Jack's verse makes me out a coxcomb, but he knew me not in my youth. He was but four, and sucking sugar-plums, when his father and I were fugitives after Worcester. Judge from this story, if he rhymes the truth of me.

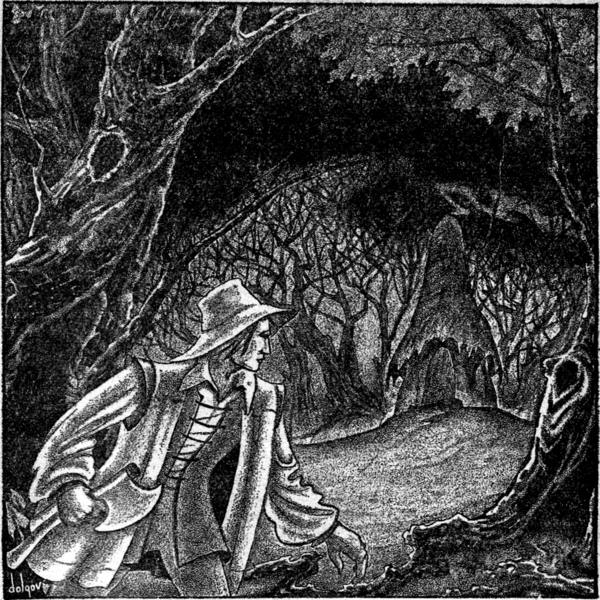

I think it was then, with the rain soaking my wretched borrowed clothes and the heavy tight plough-shoes rubbing my feet all to blisters, that I first knew consciously how misery may come to kings as to vagabonds. Egad, I was turned the second before I had well been the first. Trying to think of other things than my present sorry state among the dripping trees of Spring Coppice, I could but remember sorrier things still. Chiefly came to mind the Worcester fight, that had been rather a cutting down of my poor men like barley, and Cromwell's Ironside troopers the reapers; How could so much ill luck befall—Lauderdale's bold folly, that wasted our best men in a charge? The mazed silence of Leslie's Scots horse, the first of their blood I ever heard of before or since who refused battle? I remembered too, as a sick dream, how I charged with a few faithful at a troop of Parliamentarian horse said to be Cromwell's own guard; I had cut down a mailed rider with a pale face like the winter moon, and rode back dragging one of my own, wounded sore, across my saddle bow. He had died there, crying to me: "God save your most sacred Majesty!" And now I had need of God to save me.

"More things than Cromwell's wit and might went into this disaster," I told myself in the rain, nor knew how true I spoke.

After the battle, the retreat. Had it been only last night? Leslie's horsemen, who had refused to follow me toward Cromwell, had dogged me so close m fleeing him I was at pains to scatter and so avoid them. Late we had paused, my gentlemen and I, at a manor of White-Ladies. There we agreed to divide and flee in disguise. With trie help of two faithful yokels named Penderel I cut my long curls with a knife and crammed my big body into coarse garments—gray cloth breeches, a leathern doublet, a green jump-coat—while that my friends smeared my face and hands with chimney-soot. Then farewells, and I gave each gentleman a keep-sake—a ribbon, a buckle, a watch, and so forward. I remembered, too, my image in a mirror, and it was most unkingly—a towering, swarthy young man, ill-clad, ill-faced. One of the staunch Penderals bade me name myself, and I chose to be called Will Jones, a wandering woodcutter.

Will Jones! "Twas an easy name and comfortable. For the nonce I was happier with it than with Charles Stuart, England's king and son of that other Charles who had died by Cromwell's axe. I was heir to bitter sorrow and trouble and mystery, in my youth lost and hunted and friendless as any strong thief.

The rain was steady and weary. I tried to ask myself what I did here in Spring Coppice. It had been necessary to hide the day out, and travel by night; but whose thought was it to choose this dim, sorrowful wood? Richard Penderel had said that no rain fell elsewhere. Perhaps that was well, since Ironsides might forbear to seek me in such sorry bogs; but meanwhile I shivered and sighed, and wished myself a newt. The trees, what I could see, were broad oaks with some fir and larch, and the ground grew high with bracken reddened by September's first chill.

Musing thus, I heard a right ill sound—horses' hoofs. I threw myself half-downways among some larch scrub, peering out through the clumpy leaves. My right hand clutched the axe I carried as part of my masquerade. Beyond was a lane, and along it, one by one, rode enemy—a troop of Cromwell's horse, hard fellows and ready-seeming, with breasts and caps of iron. The)' stared right and left searchingly. The bright, bitter eyes of their officer seemed to strike through my hiding like a pike-point. I clutched my axe the tighter, and swore on my soul that, if found, I would the fighting—a better death, after all, than my poor father's.

But they rode past, and out of sight. I sat up, and wiped muck from my long nose. "I am free yet," I told myself. "One day, please our Lord, I shall sit on the throne that is mine. Then shall I seek out these Ironsides and feed fat the gallows at Tyburn, the block at the Tower."

For I was young and cruel then, as now I am old and mellow. Religion perplexed and irked me. I could not understand nor like Cromwell's Praise-God men of war, whose faces were as sharp and merciless as, alas, their swords. "I'll give them texts to quote," I vowed. "I have heard their canting war-cries. 'Smite and spare not!' They shall learn how it is to be smitten and spared not."

For the moment I felt as if vengeance were already mine, my house restored to power, my adversaries chained and delivered into my hand. Then I turned to cooler thoughts, and chiefly that I had best seek a hiding less handy to that trail through the trees.

The thought was like sudden memory, as if indeed I knew the Coppice and where best to go.

For I mind me how I rose from among the larches, turned on the heel of one pinching shoe, and struck through a belt of young spruce as though I were indeed a woodcutter seeking by familiar ways the door of mine own hut. So confidently did I stride that I blundered—or did I?—into a thorny vine that hung down from a long oak limb. It fastened upon my sleeve like urging fingers. "Nay, friend," I said to it, trying to be gay, "hold me not here in the wet," and I twitched away. That was one more matter about Spring Coppice that seemed strange and not overcanny—as also the rain, the gloom, my sudden desire to travel toward its heart. Yet, as you shall see here, these things were strange only in their basic cause. But I forego the tale.

"So cometh Will Jones to his proper home," cjuoth I, axe on shoulder. Speaking thus merrily, I came upon another lane, but narrower than that on which the horsemen had ridden. This ran ankle-deep in mire, and I remember how the damp, soaking into my shoes, soothed those plaguey blisters. I followed the way for some score of paces, and meseemed that the rain was heaviest here, like a curtain before some hidden thing. Then I came into a cleared space, with no trees nor bush, nor even grass upon the bald earth. In its center, wreathed with rainy mists, a house.

I paused, just within shelter of the leaves. "What," I wondered, "has my new magic of being a woodcutter conjured up a woodcutter's shelter?"

But this house was no honest workman's place, that much I saw with but half an eye. Conjured up it might well have been, and most foully. I gazed at it without savor, and saw that it was not large, but lean and high-looking by reason of the steep pitch of its roof. That roof's thatch was so wet and foul that it seemed all of one drooping substance, like the cap of a dark toadstool. The walls, too, were damp, being of clay daub spread upon a framework of wattles. It had one door, and that a mighty thick heavy one, of a single dark plank that hung upon heavy rusty hinges. One window it had, too, through which gleamed some sort of light; but instead of glass the window was filled with something like thin-scraped rawhide, so that light could come through, but not the shape of things within. And so I knew not what was in that house, nor at the time had I any conscious lust to find out.

I say, no conscious lust. For it was unconsciously that I drifted idly forth from the screen of wet leaves, gained and moved along a little hard-packed path between bracken-clumps. That path led to the door, and I found myself standing before it; while through the skinned-over window, inches away, I heard noises.

Noises I call them, for at first I could not think they were voices. Several soft hummings or purrings came to my ears, from what source I knew not. Finally, though, actual words, high and raspy:

"We who keep the commandment love the law! Moloch, Lucifer, Bal-Tigh-Mor, Anector, Somiator, sleep ye not! Compel ye that the man approach!"

It had the sound of a prayer, and yet I recognized but one of the names called—Lucifer. Tutors, parsons, my late unhappy allies die Scots Covenentors, had used the name oft and fearfully. Prayer within that ugly lean house went up—or down, belike—to the fallen Son of the Morning. I stood against the door, pondering. My grandsire, King James, had believed and feared such folks' pretense. My father, who was King Charles before me, was pleased to doubt and be merciful, pardoning many accused witches and sorcerers. As for me, my short life had held scant leisure to decide such a matter. While I waited in the fine misty rain on the threshold, the high voice spoke again:

"Drive him to us! Drive him to us! Drive him to us!"

Silence within, and you may be sure silence without. A new voice, younger and thinner, made itself heard: "Naught comes to us."

"Respect the promises of our masters," replied the first. "What says the book?"

And yet a new voice, this time soft and a woman's: "Let the door be opened and the wayfarer be plucked in."

I swear that I had not the least impulse to retreat, even to step aside. 'Twas as if all my life depended on knowing more. As I stood, ears aprick like any cat's, the door creaked inward by three inches. An arm in a dark sleeve shot out, and fingers as lean and clutching as thorn-twigs fastened on the front of my jump-coat.

"I have him safe!" rasped the high voice that had prayed. A moment later I was drawn inside, before I could ask the reason.

There was one room to the house, and it stank of burning weeds. There were no chairs or other furniture, and no fireplace; but in the center of the tamped-clay floor burned an open fire, whose rank smoke climbed to a hole at the roof's peak. Around this fire was drawn a circle in white chalk, and around the circle a star in red. Close outside the star were the three whose voices I had heard.

Mine eyes lighted first on she who held the book—young she was and dainty. She sat on the floor, her feet drawn under her full skirt of black stuff. Above a white collar of Dutch style, her face was round and at the same time fine and fair, with a short red mouth and blue eyes like the clean sea.

Her hair, under a white cap, was as yellow as corn. She held in her slim white hands a thick book, whose cover looked to be grown over with dark hair, like the hide of a Galloway bull.

Her eyes held mine for two trices, then I looked beyond her to another seated person. He was small enough to be a child, but the narrow bright eyes in his thin face were older than the oldest I had seen, and the hands clasped around his bony knees were rough and sinewy, with large sore-seeming joints. His hair was scanty, and eke his eyebrows. His neck showed swollen painfully.

It is odd that my last look was for him who had drawn me in. He was tall, almost as myself, and grizzled hair fell on the shoulders of his velvet doublet. One claw still clapped hold of me and his face, a foot from mine, was as dark and bloodless as earth. Its lips were loose, its quivering nose broken. The eyes, cold and wide as a frog's, were as steady as gun-muzzles.

He kicked the door shut, and let me go. "Name yourself," he rasped at me. "If you be not he whom we seek—"

"I am Will Jones, a poor woodcutter," I told him.

"Mmmm," murmured the wench with the book. "Belike the youngest of seven sons—sent forth by a cruel step-dame to seek fortune in the world. So runs the fairy tale, and we want none such. Your true name, sirrah."

I told her roundly that she was insolent, but she only smiled. And I never saw a fairer than she, not in all the courts of Europe—not even sweet Nell Gwyn. After many years I can see her eyes, a little slanting and a little hungry. Even when I was so young, women feared me, but this one did not.

"His word shall not need," spoke the thin young-old fellow by the fire. "Am I not here to make him prove himself?" He lifted his face so that the fire brightened it, and I saw hot red blotches thereon.

"True," agreed the grizzled man. "Sirrah, whether you be Will Jones the woodman or Charles Stuart the king, have you no mercy on poor Diccon yonder? If 'twould ease his ail, would you not touch him?"

That was a sneer, but I looked closer at the thin fellow called Diccon, and made sure that he was indeed sick and sorry. His face grew full of hope, turning up to me. I stepped closer to him.

"Why, with all my heart, if 'twill serve," I replied.

'"Ware the star and circle, step not within the star and circle," cautioned the wench, but I came not near those marks. Standing beside and above Diccon, I felt his brow, and felt that it was fevered. "A hot humor is in your blood, friend," I said to him, and touched the swelling on his neck.

But had there been a swelling there? I touched it, but 'twas suddenly gone, like a furtive mouse under my finger. Diccon's neck looked lean and healthy. His face smiled, and from it had fled the red blotches. He gave a cry and sprang to his feet

"'Tis past, 'tis past!" he howled. "I am whole again!"

But the eyes of his comrades were for me.

"Only a king could have done so," quote the older man. "Young sir, I do take you truly for Charles Stuart. At your touch Diccon was healed of the king's evil."

I folded my arms, as if I must keep my hands from doing more strangeness. I had heard, too, of that old legend of the Stuarts, without deeming myself concerned. Yet, here it had befallen. Diccon had suffered from the king's evil, which learned doctors call scrofula. My touch had driven it from his thin body. He danced and quivered with the joy of health. But his fellows looked at me as though I had betrayed myself by sin.

"It is indeed the king," said the girl, also rising to her feet.

"No," I made shift to say. "I am but poor Will Jones," and I wondered where I had let fall my axe. "Will Jones, a woodcutter."

"Yours to command, Will Jones," mocked the grizzled man. "My name is Valois Pembru, erst a schoolmaster. My daughter Regan," and he flourished one of his talons at the wench. "Diccon, our kinsman and servitor, you know already, well enough to heal him. For our profession, we are—are—"

He seemed to have said too much, and his daughter came to his rescue. "We are liers in wait," she said.

"True, liers in wait," repeated Pembru, glad of the words. "Quiet we bide our time, against what good things comes our way. As yourself, Will Jones. Would you sit in sooth upon the throne of England? For that question we brought you hither."

I did not like his lofty air, like a man cozening puppies. "I came myself, of mine own good will," I told him. "It rains outside."

"True," muttered Diccon, his eyes on me. "All over Spring Coppice falls the rain, and not elsewhere. Not one, but eight charms in yonder book can bring rain—'twas to drive your honor to us, that you might heal—"

"Silence," barked Valois Pembru at him. And to me: "Young sir, we read and prayed and burnt," and he glanced at the dark-orange flames of the fire. "In that way we guided your footsteps to the Coppice, and the rain then made you see this shelter. 'Twas all planned, even before Noll Cromwell scotched you at Worcester—"

"Worcester!" T roared at him so loudly that he stepped back. "What know you of Worcester fight?"

He recovered, and said in his erst lofty fashion: "Worcester was our doing, too. We gave the victory to Noll Cromwell. At a price—from the book."

He pointed to the hairy tome in the hands of Regan, his daughter. "The flames showed us your pictured hosts and his, and what befell. You might have stood against him, even prevailed, but for the horsemen who would not right."

I remembered that bitter amazement over how Leslie's Scots had bode like statues. "You dare say you wrought that?"

Pembru nodded at Mistress Regan, who turned pages. "I will read it without the words of power," quoth she. "Thus: 'In meekness I begin my work. Stop rider! Stop footman! Three black flowers bloom, and under them ye must stand still as long as I will, not through me but through the name of—"

She broke off, staring at me with her slant blue eyes. I remembered all the tales of my grandfather James, who had fought and written against witchcraft. "Well, then, you have given the victory to Cromwell. You will give me to him also?"

Two of the three laughed—Diccon was still too mazed with his new health—and Pembru shook his grizzled head. "Not so, woodcutter. Cromwell asked not the favor from us—'twas one of his men, who paid well. We swore that old Noll should prevail from the moment of battle. But," and his eyes were like gimlets in mine, "we swore by the oaths set us—the names Cromwell's men worship, not the names we worship. We will keep the promise as long as we will, and no longer."

"When it pleases us we make," contributed Regan. "When it pleases us we break."

Now 'tis true that Cromwell perished on third September, 1658, seven year to the day from Worcester fight. But I half-believed Pembru even as he spoke, and so would you have done. He seemed to be what he called himself—a lier in wait, a bider for prey, myself or others. The rank smoke of the fire made my head throb, and I was weary of being played with. "Let be," I said. "I am no mouse to be played with, you gibbed cats. What is your will?"

"Ah," sighed Pembru silkily, as though he had waited for me to ask, "what but that our sovereign should find his fortune again, scatter the Ironsides of the Parliament in another battle and come to his throne at Whitehall?"

"It can be done," "Regan assured me. "Shall I find the words in the book, that when spoken will gather and make resolute your scattered, running friends?"

I put up a hand. "Read nothing. Tell me rather what you would gain thereby, since you seem to be governed by gains alone."

"Charles Second shall reign," breathed Pembru. "Wisely and well, with thoughtful distinction. He will thank his good councillor the Earl—no, the Duke—of Pembru. He will be served well by Sir Diccon, his squire of the body."

"Served well, I swear," promised Diccon, with no mockery to his words.

"And," cooed Regan, "are there not ladies of the court? Will it not be said that Lady Regan Pembru is fairest and—most pleasing to the king's grace?"

Then they were all silent, waiting for me to speak. God pardon me my many sins! But among them has not been silence when words are needed. I laughed fiercely.

"You are three saucy lackeys, ripe to be flogged at the cart's tail," I told them. "By tricks you learned of my ill fortune, and seek to fatten thereon." I turned toward the door. "I sicken in your company, and I leave. Let him hinder me who dare."

"Diccon!" called Pembru, and moved as if to cross my path. Diccon obediently ranged alongside. I stepped up to them.

"If you dread me not as your ruler, dread me as a big man and a strong," I said. "Step from my way, or I will smash your shallow skulls together."

Then it was Regan, standing across the door.

"Would the king strike a woman?" she challenged. "Wait for two words to be spoken. Suppose we have the powers we claim?"

"Your talk is empty, without proof," I replied. "No. mistress, bar me not. I am going."

"Proof you shall have," she assured me hastily. "Diccon, stir the fire."

He did so. Watching, I saw that in sooth he was but a lad—his disease, now banished by my touch, had put a false seeming of age upon him. Flames leaped up, and upon them Pembru cast a handful of herbs whose sort I did not know. The color of the fire changed as I gazed, white, then rosy red, then blue, then again white. The wench Regan was babbling words from the hair-bound book; but, though I had. learned most tongues in my youth, I could not guess what language she read.

"Ah, now," said Pembru. "Look, your gracious majesty. Have you wondered of your beaten followers?"

In the deep of the fire, like a picture that forebore burning and moved with life, I saw tiny figures—horsemen in a huddled knot riding in dejected wise. Though it was as if they rode at a distance, I fancied that I recognized young Straike—a cornet of Leslie's. I scowled, and the vision vanished.

"You have prepared puppets, or a shadow-show," I accused. "I am no country hodge to be tricked thus."

"Ask of the fire what it will mirror to you," bade Pembru, and I looked on him with disdain.

"What of Noll Cromwell?" I demanded, and on the trice he was there. I had seen the fellow once, years agone. He looked more gray and bloated and fierce now, but it was he—Cromwell, the king rebel, in back and breast of steel with buff sleeves. He stood with wide-planted feet and a hand on his sword. I took it that he was on a porch or platform, about to speak to a throng dimly seen.

"You knew that I would call for Cromwell," I charged Pembru, and the second image, too, winked out.

He smiled, as if my stubbornness was what he loved best on earth. "Who else, then? Name one I cannot have prepared for."

"Wilmot," I said, and quick anon I saw him. Poor nobleman! He was not young enough to tramp the byways in masquerade, like me. He rode a horse, and that a sorry one, with his pale face cast down. He mourned, perhaps for me. I felt like smiling at this image of my friend, and like weeping, too.

"Others? Your gentlemen?" suggested Pembru, and witliuut my naming they sprang into view one after another, each in a breath's space. Their faces flashed among the shreds of flame—Buckingham, elegant and furtive; Lauderdale, drinking from a leather cup; Colonel Carlis, whom we called "Careless," though he was never that; the brothers Penderel, by a fireside with an old dame who may have been their mother; suddenly, as a finish to the show, Cromwell again, seen near with a bible in his hand.

The fire died, like a blown candle. The room was dim and gray, with a whisp of smoke across the hide-spread window.

"Well, sire? You believe?" said Pembru. He smiled now, and I saw teeth as lean and white as a hunting dog's.

"Faith, only a fool would refuse to believe," I said in all honesty.

He stepped near. "Then you accept us?" he questioned hoarsely. On my other hand tiptoed the fair lass Regan.

"Charles!" she whispered. "Charles, my comely king!" and pushed herself close against me, like a cat seeking caresses.

"Your choice is wise," Pembroke said on. "Spells bemused and scattered your army—spells will bring it back afresh. You shall triumph, and salt England with the bones of the rebels. Noll Cromwell shall swing from a gallows, that all like rogues may take warning. And you, brought by our powers to your proper throne—"

"Hold," I said, and they looked upon me silently.

"I said only that I believe in your sorcery," I told them, "but I will have none of it."

You would have thought those words plain and round enough. But my three neighbors in that ill house stared mutely, as if I spoke strangely and foolishly. Finally: "Oh, brave and gay! Let me perish else!" quoth Pembru, and laughed.

My temper went, and with it my bemusement. "Perish you shall, dog, for your saucy ways," I promised. "What, you stare and grin? Am I your sovereign lord, or am I a penny show? I have humored you too long. Good-bye."

I made a step to leave, and Pembru slid across my path. His daughter Regan was opening the book and reciting hurriedly, but I minded her not a penny. Instead, I smote Pembru with my fist, hard and fair in the middle of his mocking face. And down he went, full-sprawl, rosy blood fountaining over mouth and chin.

"Cross me again," quoth I, "and I'll drive you into your native dirt like a tether-peg." With that, I stepped across his body where it quivered like a wounded snake, and put forth my hand to open the door.

There was no door. Not anywhere in the room.

I turned back, the while Regan finished reading and closed the book upon her slim finger.

"You see, Charles Stuart," she smiled, "you must bide here in despite of yourself."

"Sir, sir," pleaded Diccon, half-crouching like a cricket, "will you not mend your opinion of us?"

"I will mend naught," I said, "save the lack of a door." And I gave the wall a kick that shook the stout wattlings and brought down flakes of clay. My blistered foot quivered with pain, but another kick made some of the poles spring from their fastenings. In a moment I would open a way outward, would go forth.

Regan shouted new words from the book. I remember a few, like uncouth names—Sator, Arepos, Janna. I have heard since that these are powerful matters with the Gnostics. In the midst of her outcry, I thought smoke drifted before me—smoke |hat stank like dead flesh, and thickened into globes and curves, as if it would make a form. Two long streamers of it drifted out like snakes, to touch or seize me, I gave back, and Regan stood at my side.

"Would you choose those arms," asked she. "and not these?" She held out her own, fair and round and white. "Charles, I charmed away the door. I charmed that spirit to hold you. I will still do you good in despite of your will—you shall reign in England, and I—and I——"

Weariness was drowning me. I felt like a child, drowsy and drooping. "And you?" I said.

"You shall tell me," she whispered. "Charles."

She shimmered in my sight, and bells sang as if to signal her victory. I swear it was not I who spoke then stupidly—cunsult Jack Wilmot's doggerel to see if I am wont to be stupid. But the voice came from my mouth: "I shall be king in Whitehall."

She prompted me softly: "I shall be duchess, and next friend—"

"Duchess and next friend," I repeated.

"Of the king's self!" she finished, and I opened my mouth to say that, too. Valois Pembru, recovering from my buffet, sat up and listened.

But——

"STOP!" roared Diccon.

We all looked—Regan and I and Valois Pembru. Diccon rose from where he crouched. In his slim, strong hands was the foul hairy book that Regan had laid aside. His finger marked a place on the open page.

"The spells are mine, and I undo what they have wrought!" he thundered in his great new voice. "Stop and silence! Look upon me, ye sorcerers and arch-sorcerers! You who attack Charles Stuart, let that witchcraft recede from him into your marrow and bone, in this instant and hour—"

He read more, but I could not hear for the horrid cries of Pembru and his daughter.

The rawhide at the window split, like a drum-head made too hot. And cold air rushed in. The fire that had vanished leaped up, its flames bright red and natural now. Its flames scaled the roof-peak, caught there. Smoke, rank and foul, crammed the place. Through it rang more screams, and I heard Regan, pantingly:

"Hands—from—my—throat——!"

Whatever had seized her, it was not Diccon, for he was at my side, hand on my sleeve.

"Come, sire! This way!"

Whither the door had gone, thither it now came back. We found it open before us, scrambled through and into the open.

The hut burnt behind us like a hayrick, and I heard no more cries therefrom. "Pembru!" I cried. "Regan! Are they slain?"

"Slain or no, it does, not signify," replied Diccon. "Their ill magic retorted upon them. They are gone with it from earth—forever." He hurled the hairy book into die midst of the flame. "Now, away."

We left the clearing, and walked the lane. There was no more rainfall, no more mist. Warm light came through the leaves as through clear green water.

"Sire," said Diccon, "I part from you. God bless your kind and gracious majesty! Bring you safe to your own place, and your people to their proper senses."

He caught my hand and kissed it, and would have knelt. But I held him on his feet.

"Diccon," I said, "I took you for one of those liers in wait. But you have been my friend this day, and I stand in your debt as long as I live."

"No, sire, no. Your touch drove from me the pain of the king's evil, which had smitten me since childhood, and which those God-forgotten could not heal with all their charms. And, too, you refused witch-help against Cromwell."

I met his round, true eye. "Sooth to say, Cromwell and I make war on each other," I replied, "but——"

"But 'tis human war," he said for me. "Each in his way hates hell. 'Twas bravely done, sire. Remember that Cromwell's course is run in seven years. Be content until then. Now—Godspeed!"

He turned suddenly and made off amid the leafage. I walked on alone, toward where the brothers Penderel would rejoin me with news of where next we would seek safety.

Many things churned in my silly head, things that have not sorted themselves in all the years since; but this came to the top of the churn like fair butter.

The war in England was sad and sorry and bloody, as all wars. Each party called the other God-forsaken, devilish. Each was wrong. We were but human folk, doing what we thought well, and doing it ill. Worse than any human foe was sorcery and appeal to the devil's host.

I promise myself then, and have not since departed from it, that when I ruled, no honest religion would be driven out. All and any such, I said in my heart, was so good that it bettered the worship of evil. Beyond that, I wished only for peace and security, and the chance to take off my blistering shoes.

"Lord," I prayed, "if thou art pleased to restore me to the throne of my ancestors, grant me a heart constant in the exercise and protection of true worship. Never may I seek the oppression of those who, out of tenderness of their consciences, are not free to conform to outward and indifferent ceremonies."

And now judge between me and Jack Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. There is at least one promise I have kept, and at least one wise deed I have done. Put that on my grave.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was legally published within the United States (or the United Nations Headquarters in New York subject to Section 7 of the United States Headquarters Agreement) before 1964, and copyright was not renewed.

- For Class A renewals records (books only) published between 1923 and 1963, check the Stanford University Copyright Renewal Database.

- For other renewal records of publications between 1922–1950 see the University of Pennsylvania copyright records scans.

- For all records since 1978, search the U.S. Copyright Office records.

- See also the Rutgers copyright renewal records for further information.

Works published in 1941 would have had to renew their copyright in either 1968 or 1969, i.e. at least 27 years after they were first published/registered but not later than 31 December in the 28th year. As this work's copyright was not renewed, it entered the public domain on 1 January 1970.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1986, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 37 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

It is imperative that contributors search the renewal databases and ascertain that there is no evidence of a copyright renewal before using this license. Failure to do so will result in the deletion of the work as a copyright violation.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse