1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Theodoric

THEODORIC, king of the Ostrogoths (c. 454–526). Referring to the article Goths for a general statement of the position of this, the greatest ruler that the Gothic nation produced, we add here some details of a more personal kind. Theodoric was born about the year 454, and was the son of Theudemir, one of three brothers who reigned over the East Goths, at that time settled in Pannonia. The day of his birth coincided with the arrival of the news of a victory of his uncle Walamir over the sons of Attila. The name of Theodoric’s mother was Erelieva, and she is called the concubine of Theudemir. The Byzantine historians generally call him son of Walamir, apparently because the latter was the best known member of the royal fraternity. At the age of seven he was sent as a hostage to the court of Constantinople, and there spent ten years of his life, which doubtless exercised a most important influence on his subsequent career. Soon after his return to his father (about 471) he secretly, with a comitatus of 10,000 men, attacked the king of the Sarmatians, and wrested from him the important city of Singidunum (Belgrade). In 473 Theudemir, now chief king of the Ostrogoths, invaded Moesia and Macedonia, and obtained a permanent settlement for his people near Thessalonica. Theodoric took the chief part in this expedition, the result of which was to remove the Ostrogoths from the now barbarous Pannonia, and to settle them as foederati in the heart of the empire. About 474 Theudemir died, and for the fourteen following years Theodoric was chiefly engaged in a series of profitless wars, or rather plundering expeditions, partly against the emperor Zeno, but partly against a rival Gothic chieftain, another Theodoric, son of Triarius.[1] In 488 he set out at the head of his people to win Italy from Odoacer. There is no doubt that he had for this enterprise the sanction of the emperor, only too anxious to be rid of so troublesome a guest. But the precise nature of the relation which was to unite the two powers in the event of Theodoric’s success was, perhaps purposely, left vague. Theodoric’s complete practical independence, combined with a great show of deference for the empire, reminds us somewhat of the relation of the old East India Company to the Mogul dynasty at Delhi, but the Ostrogoth was sometimes actually at war with his imperial friend. The invasion and conquest of Italy occupied more than four years (488–493). Theodoric, who marched round the head of the Venetian Gulf, had to fight a fierce battle with the Gepidae, probably in the valley of the Save. At the Sontius (Isonzo) he found his passage barred by Odoacer, over whom he gained a complete victory (28th of August 489). A yet more decisive victory followed on the 30th September at Verona. Odoacer fled to Ravenna, and it seemed as if the conquest of Italy was complete. It was delayed, however, for three years by the treachery of Tufa, an officer who had deserted from the service of Odoacer, and of Frederic the Rugian, one of the companions of Theodoric, as well as by the intervention of the Burgundians on behalf of Odoacer. A sally was made from Ravenna by the besieged king, who was defeated in a bloody battle in the Pine Wood. At length (26th of February 493) the long and severe blockade of Ravenna was ended by a capitulation, the terms of which Theodoric disgracefully violated by slaying Odoacer with his own hand (15th of March 493). (See Odoacer.)

The thirty-three years’ reign of Theodoric was a time of unexampled happiness for Italy. Unbroken peace reigned within her borders (with the exception of a trifling raid made by Byzantine corsairs on the coast of Apulia in 508). The venality of the Roman officials and the turbulence of the Gothic nobles were sternly repressed. Marshes were drained, harbours formed, the burden of the taxes lightened, and the state of agriculture so much improved that Italy, from a corn-importing, became a corn-exporting country. Moreover Theodoric, though adhering to the Arian creed of his forefathers, was during the greater part of his reign so conspicuously impartial in religious matters that a legend which afterwards became current represented him as actually putting to death a Catholic deacon who had turned Arian in order to win his favour. At the time of the contested papal election between Symmachus and Laurentius (496-502), Theodoric's mediation was welcomed by both contending parties. Unfortunately, at the very close of his reign (524), the Emperor Justin's persecution of the Arians led him into a policy of reprisals. He forced Pope John to undertake a mission to Constantinople to plead for toleration, and on his return threw him into prison, where he died. Above all, he sullied his fame by the execution of Boetius and Symmachus (see Boetius). It should be observed, however, that the motive for these acts of violence was probably political rathef than religious—jealousy of intrigues with the imperial court rather than zeal on behalf of the Arian confession. Theodoric's death, which is said to have been hastened by remorse for the execution of Symmachus, occurred on the 30th of August 526. He was buried in the mausoleum which is still one of the marvels of Ravenna (q.v.), and his grandson Athalaric, a boy of ten years, succeeded him, under the regency of his mother Amalasuntha.

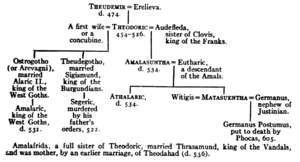

Genealogy of Theodoric.

{{sc|Theudemir}} d. 474. ┬ Erelieva A first wife or a concubine. ┬ {{sc|Theodoric}}. ┬ Audeflada, sister of Clovis, king of the Franks. Ostrogotho (or Arevagni), married Alaric II., king of the West Goths.<br> │<br> Amalaric, king of the West Goths, d. 531. Theudegotho, married Sigismund, king of the Burgundians.<br> │<br> Segeric, murdered by his father's orders, 522. {{sc|Amalasuntha}} d. 534. ┬ Eutharic, a descendant of the Amals. {{sc|Athalaric}}, d. 534. Witigis ┬ {{sc|Matasuentha}} ┬ Germanus, nephew of Justinian. Germanus Postumus, put to death by Phocas, 605. Amalafrida, a full sister of Theodoric, married Thrasamund, king of the Vandals, and was mother, by an earlier marriage, of Theodahad (d. 536).

Authorities.—The authorities for the life of Theodoric are very imperfect. Jordanes, Procopius, and the curious fragment known as Anonymus Valesii (printed at the end of Ammianus Marcellinus) are the chief direct sources of narrative, but far the most important indirect source is the Variae (state-papers) of Cassiodorus, chief minister of Theodoric. Malchus furnishes some interesting particulars as to his early life, and it is possible to extract a little information from the turgid panegyric of Ennodius. Among German scholars F. Dahn (Könige der Germanen, ii., iii. and iv.), J. K. F. Manso (Geschichte des Ostgothischen Reichs in Italien, 1824), and Sartorius (Versuch uber die Regierung der Ostgothen, &c.) have done most to illustrate Theodoric's principles of government. The English reader may consult Gibbon's Decline and Fall, chap, xxxix., and Hodgkin's Italy and her Invaders, vol. iii. (1885), his introduction to Letters of Cassiodorus (1886) and Theodoric the Goth (London and New York, 1891). For the legends connected with the name of Theodoric see the article Dietrich of Bern.

- ↑ In one of the intervals of friendship with the emperor in 483 Theodoric was made master of the household troops and in 484 consul.