A Brief History of Wood-engraving/Chapter 11

CHAPTER XI

IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES IN GERMANY, ITALY AND ENGLAND

In the portfolios of collectors of works of art of the sixteenth century we frequently meet with very interesting examples of printing in chiaro-oscuro, as it was called, by means of successive impressions of engraved wood-blocks. Sometimes two or three blocks were used, sometimes six or eight, in all cases with the intention of reproducing the appearance of a tinted water-colour drawing or an oil-painting. Those prints which were the least ambitious were the most successful, They were generally printed in various shades of grey and brown—from light sepia to deep umber—and sometimes the effects are admirable. A well-known designer and engraver on wood, Ugo da Carpi (c. 1520), introduced this new style of printing into Venice, and other artists, Antonio da Trento, Andrea Andreani, Bartolomeo Coriolano, and others made many successful efforts in a similar direction; their best works are much prized.

At the same time a group of Venetian artists, who were also engravers on wood, distinguished themselves by copying the works of Titian and other Italian painters. The most celebrated of these engravers were Nicolo Boldrini, Francesco da Nanto, Giovanni Battista del Porto, and Giuseppe Scolari, who all flourished between the years 1530 and 1580. Their productions, which are on a large scale, are greatly valued by artists.

Near the end of the century a book of costume entitled Habiti Antichi e Moderni di tutto il Mondo was designed and published at Venice by Cesare Vecellio, who is said to have been a nephew of the great Titian. This work contains nearly six hundred figures in the costume of every age and country, admirably drawn and engraved; indeed, they are the best examples of the art of wood-engraving in Italy at the time. This excellent work was reproduced in their well-known style by Messrs. Firmin, Didot & Cie in two volumes (Paris, 1860).

An edition of 'Dante' published by the brothers Sessa at Venice in 1578 is well illustrated with good woodcuts.

German artists were also bitten at this time with a mania for reproducing pictures by means of colour blocks. The results, however, were much more curious than beautiful. We have before us a copy of a painting designed by Altdorfer, one of the 'Little Masters,' of 'The Virgin with the Holy Infant on her Lap,' set in an elaborate architectural frame. In this print at least eight different colour-blocks were used, among them a deep red and a vivid green. The printer's register has been fairly well kept, and the mechanical part of the work is worthy of all praise; but we fear the effect on most of our readers would be to produce anything but admiration. A Saint Christopher, designed and probably engraved by Lucas Cranach, printed in black and deep umber, only with the high lights carefully cut out of the latter block, is much more satisfactory.

In the middle and towards the end of the sixteenth century there were several excellent wood-engravings published in London in illustration of Foxe's 'Book of Martyrs' (1562), Holinshed's 'Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland' (1577), 'A Booke of Christian Prayers' (1569), and other works, chiefly from the press of the celebrated John Daye.

PORTRAIT OF JOHN DAYE, THE CELEBRATED PRINTER OF FOXE'S 'BOOK OF MARTYRS,' A.D. 1562

As an example we give one of the illustrations of Holinshed's Chronicles as a frontispiece. There can be no doubt that Holbein designed it; the ornamentation alone would almost prove it to be from his hand. The title-page of the 'Bishops' Bible,' printed about the same time, has a finely engraved border, representing the King handing the volume to the Bishops, who in turn present it to the people. There are many woodcuts in the text, but they are of very low merit.

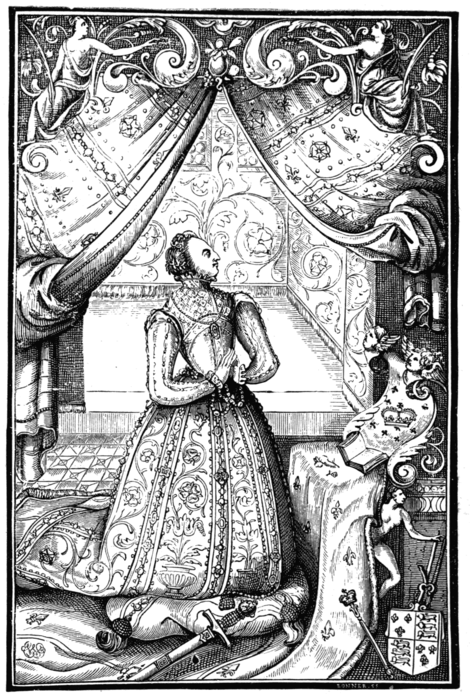

We give an illustration of 'A Booke of Christian Prayers,' known as Queen Elizabeth's Prayer-book, from a fine portrait of Her Majesty kneeling on a handsome cushion, with clasped hands before a kind of altar. The Queen's dress is magnificent, and the ornamentation of the whole design is of a similar character. It is an excellent piece of engraving, and we are able to give a facsimile of it, cut about sixty years ago by George Bonner. Mr. Linton thinks the original was on metal; who engraved it is at present unknown. We fear there was no one in England who could produce such work, nor can anyone tell who made the design. It is printed on the back of the title-page, which is decorated with a border of a 'Jesse-tree,' with a figure of Jesse at the foot and the Virgin with the Holy Infant on her lap at the head. There are woodcut borders to each of the 274 pages, all betraying German origin, and evidently by different hands. A few floral designs and single figures of 'Temperance,' 'Charity,' and the like are the best. Among the rest is a series of 'Dance of Death' pictures, but not by Holbein. Another edition of this work was printed in 1590 at London, 'By Richard Yardley and Peter Short for the assignes of Richard Day dwelling in Bred-street hill at the signe of the Starre.' [Doubtless this was on the site of the present printing office of Richard Clay & Sons.] Richard Day was a son of John Day or Daye, as we often find the name printed.

ELIZABETHA REGINA

(From 'A Booke of Christian Prayers.' Printed by John Daye, London, 1569.)

Another illustrated book, 'The Cosmographical Glasse, conteinyng the pleasant Principles of Cosmographie, Geographie, Hydrographie or Navigation. Compiled by William Cuningham, Doctor in Physicke' (of Norwich), was printed by John Day in 1559, with many cuts. In the ornamental title-page there is a large bird's-eye view of the city of Norwich, with a mark of the engraver, I. B. There is also a large and well-engraved portrait of the author, 'ætatis 28,' a rather sad-looking young man; and many initial letters, some of which have a small I. D. at the foot, which probably tell us that John Day himself engraved them. Others have a small I inside a larger C, and this monogram appears frequently on the small cuts in the border of Queen Elizabeth's Book of Prayers. John Day tells us in a work published in 1567 that the Saxon type in which it is printed was cut by himself.

John Day was a great friend of John Foxe, and assisted him in producing his celebrated 'Acts and Monuments of the Church,' generally known as his 'Booke of Martyrs.' In the 'Acts and Monuments,' printed in 1576, there is a large initial C, evidently drawn and engraved by the artists who produced the Queen's portrait. In this initial, Elizabetha Regina is seen seated in state, with her feet resting on the same cushion that appears in the larger print, attended by three of her Privy Councillors standing at her right hand. A figure of the Pope with two broken keys in his hands forms part of the decoration of the base; an immense cornucopia reaches over the top.

Early in the seventeenth century we meet with the name of an excellent wood-engraver at Antwerp, Christoph Jegher, who worked for many years with Peter Paul Rubens, and produced many large woodcuts. We are enabled to give a much-reduced copy of a 'Flight into Egypt,' which in the original is nearly twenty-four inches in length. Underneath appears the inscription, P. P. Rub. delin. & excud., from which we learn that Rubens himself superintended the printing, for C. Jegher sculp. appears on the other side. Some of this series of cuts were printed with a tint of sepia over them in imitation of the Italian chiaro-oscuro prints of the previous century. Christoph Jegher was born in Germany in 1590 (?) and died at Antwerp in 1670. He lived through many tempestuous years and did much good work. A contemporary wood-engraver named Cornelius van Sichem, living at Amsterdam, produced a few excellent cuts from drawings by Heinrich Goltzius (d. 1617), who copied the Italian school.

THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT. BY RUBENS

Reduced copy of the engraving by C. Jegher

At the end of the seventeenth century the art of wood-engraving reached its lowest ebb. There were a few tolerably good mechanical engravers on the Continent, who were chiefly employed in the manufacture of ornaments for cards, and head and tail pieces for books and ballads, but nearly all the woodcuts we meet with in English books are of the most childish character. The rage for copper-plate engravings had set in with so much vigour among all the printers and publishers that the poor wood-engraver was well-nigh forgotten.

In London a new edition of 'Æsop's Fables,' edited by Dr. Samuel Croxall, and illustrated with many woodcuts much better engraved than was customary at the time, was published by Jacob Tonson at the Shakespear's Head, in the Strand, in 1722. We do not learn the names of the artists. In 1724 Elisha Kirkall engraved and published seventeen Views of Shipping, from designs by W. Vandevelde, which he printed in a greenish kind of ink; and in a portfolio full of woodcuts in the Print Room of the British Museum Mr. W. J. Linton recently discovered a large Card of Invitation (query—to a wedding?) from Mr. Elisha and Mrs. Elizabeth Kirkall, dated 'August the 31st, 1709. Printed at His Majesty's Printing Office in Blackfryers,' which is very firmly and boldly engraved, probably in soft metal. On the left of the Royal Arms, Fame, blowing a trumpet, holds up a circular medallion portrait of Guttenburgh (we follow the spelling); a similar figure on the right holds the portrait of W. Caxton and a scroll; at the foot, in the middle, is a view of London Bridge over the Thames, with the Monument and St. Paul's Cathedral, and on either side is a Cupid—one with a torch and a dove, with masonic emblems at his feet, the other with attributes of painting, sculpture, and music. The Cupids are very like the fat-faced little cherubim we so constantly meet with on seventeenth-century monuments, though Mr. Linton has nothing but praise to give to the engraving, which he says is the first example of the use of the 'white line' in English work.

In Paris there was a family of three generations of engravers named Papillon, who illustrated hundreds of books with small and very fine cuts, in evident imitation of the copper-plates then so much in vogue. Jean Michel Papillon, the youngest of them, published a Traité Historique et Pratique de la Gravure en Bois, in two volumes with a supplement, which, though full of credulous errors, has been of inestimable service to all writers on the history of wood-engraving. This Papillon was probably in England at one time, for he received a prize from the Society of Arts. He was born in the year 1698, began to engrave blocks when only eight years old, and lived till the year 1776.