America's Highways 1776–1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program/Part 1/Chapter 7

Beginning

of

Scientific

Roadbuilding

The appointment of Logan Waller Page as Director of the Office of Public Roads brought a new type of leader—the scientifically trained civil servant—into the highway movement. In 1893, when only 23 years of age, Page was appointed director of the road materials laboratory of the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard University and also geologist and testing engineer of the Massachusetts State Highway Commission. At this time, although standard practice in France, the laboratory testing of road materials was unknown in the United States. Page enrolled in the French Laboratory of Bridges and Roads where he learned the French methods, introducing them later into his Massachusetts laboratory.[1] After 7 years of distinguished work for the Commission, Page was invited to Washington in 1900 to set up a road materials laboratory in the Bureau of Chemistry of the Department of Agriculture.[2] This laboratory tested thousands of specimens for the OPRI under the object lesson road program, and Page was instrumental in establishing testing laboratories in some of the States. In the reorganization of 1905, Page’s laboratory became the Division of Tests of the Office of Public Roads and eventually one of the world’s famous physical research organizations.

The Jefferson Highway near DeQueen, Arkansas, before improvement.

The Jefferson Highway after improvement as a gravel road.

Expansion of the Object Lesson Road Program

When Page became director of the Office of Public Roads (OPR) in 1905, only 14 States had highway departments, and 5 of these were less than 6 months old.[N 1] The mileage of roads under State control was very small, and State expenditures, mostly in the form of aid to the counties and townships, were only about 3 percent of total road expenditures in the United States.[N 2]

It was as evident to Director Page as it had been to his predecessors that the main effort for improving the rural roads would have to be directed to the counties and townships. Up to this time, the OPR’s most popular work with the local governments had been the object lesson roads, and already ample evidence of their effectiveness was beginning to accumulate. This evidence was summarized by Director Dodge in 1904:

. . . a section of good road built as an object lesson under the direction of the United States Government in any community has the effect of awakening much greater interest than such a road constructed by the local authorities. That the people desire instruction by the building of object lesson roads and are willing to bear the expense incident thereto is fully proved by the requests received for cooperation, the number being far more than we are able to comply with. That the results are almost uniformly satisfactory and frequently beyond the most sanguine expectation is demonstrated by reference to the letters embodied in this report from representative citizens in the sections where the roads were built and by personal investigations by representatives of this Office. In some instances the object lesson resulted in the slow but steady improvement of the common roads; in a few cases the results were the inauguration of extensive systems of road building. In practically every instance some measure of progress resulted from the object lesson. It would seem to be conservative to estimate that an average of at least 10 miles of improved highways are constructed as a result of the building of each of these roads. . . .[5]

- ↑ Massachusetts (organized 1893), New Jersey (1894), Connecticut (1895), Rhode Island (1896), New York (1898), Vermont (1898), Pennsylvania (1903), Ohio (1904), Iowa (1904), Illinois (1905), Michigan (1905), Minnesota (1905), New Hampshire (1905), Washington (1905).[3]

- ↑ In 1904 total road expenditure, including the estimated value of statute labor, was $79.77 million, of which $2.6 million was State aid.[4]

. . . Experience has shown that our earth roads can, in general, be very much improved by proper construction and systematic maintenance at a cost well within the reach of almost any community. Furthermore, these improved earth roads serve as the best possible foundation for further improvements with a hard surface as means become available. . . .[6]

Post road in Lauderdale County, Alabama. Small hump in distance is chert which will be cut and used for surfacing.

The concept of stage construction, enunciated by Page in the above quotation, became one of the guiding principles of Federal road policy for the next 50 years.

During 1908, 1909 and 1910, the OPR supervised the construction of 1,300 miles of earth roads and 440 miles of sand-clay roads.[N 1] Inevitably, object lesson roads to demonstrate the use of local materials became, in some respects, experimental roads as well. The OPR’s Road Expert, W. L. Spoon, who was handling the object lesson road work in the southern States, thought that clay might be made into a suitable road surfacing material by burning or roasting it in place on the road. A small experimental project was set up the summer of 1904 near Clarksdale, Mississippi, in which 300 feet of clay “gumbo” road was burned by wood and bark fires until the clay was nonplastic. The resulting surface compared favorably to gravel and cost only one-fourth as much.[8]

The OPR also cooperated in the construction of experimental sand-clay roads in Iowa, Kansas and Nebraska to determine whether sand-clay was suitable for areas with cold climates and deep frost penetration.

Sand-clay road in San Patricio County, Texas. Smoothing with road drag after rain. No roller available and the road is not yet thoroughly compacted by traffic.

Experimental Roads Expand Knowledge of Roadbuilding

These experiments were not the first in which the Office had been involved. In 1898, the Office of Public Road Inquiries had built short steel trackway roads at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition at Omaha and at Ames, Iowa, and St. Anthony Park, Minnesota. These proved to be impractical. Another experimental trackway road, this one of bricks, was built on the Department of Agriculture grounds in Washington in 1900. The most important of these early experiments, however, was the oil treatment of a 4,650-foot section of the Queens Chapel Road in the District of Columbia.

In 1900 the automobile was not a significant cause of road dusting, and road oiling was practically unknown outside of Los Angeles County, California, where 6 miles of road were oiled in 1898 to lay the dust “which, churned beneath the wheels of yearly increasing travel during the long dry season in that region, had become a most serious nuisance.”[9] The Queens Chapel Road had a surface of sandy clay and loam. This was shaped up and sprinkled with oil delivered by an ordinary water-sprinkling wagon.

The oil used for this experiment was “that which is left of crude petroleum after such volatile substances as naptha, kerosene, benzine and gasoline have been extracted.” The results of the treatment appeared to be good, but the OPRI elected to reserve judgment on its ultimate effectiveness:The ordinary sprinkling wagon was found quite satisfactory, especially as the weather was warm, so that the oil ran quite fast enough to be gradually taken up by the surface and not so fast that it would flow into the side ditches, as would have been the case had the required amount been applied at once.[10]

This road was treated several weeks ago, and so far as we are now able to judge the new system is a success as a dust layer. We believe that where roads have so much traffic and dust as to require the use of the sprinkling cart in dry weather, the residue oil, or roadbed oil, as it is called by dealers, could be used very effectively and economically. The fact that it settles the dust and kills weeds was first recognized and utilized by the West Jersey and Seashore Railroad. It is now being applied annually to about thirty of the leading railroads throughout the country, and its use is being gradually extended to the ordinary country roads. It is claimed by some that the application of crude oil will make a surface impervious to water, and consequently comparatively free from frost and mud. If this be the case, oil will supersede gravel and stone in the improvement of country roads. The test of time alone can settle this very much disputed question.[11]

Out of these early experiments there gradually evolved a new program, the object of which was not so much to demonstrate good construction practice as to acquire new knowledge and experience.

In 1908 the OPR began a study to determine whether blast furnace slag could be made into a suitable road aggregate by mixing it with lime, limestone, tar or asphaltic road oil. This investigation had an immense economic potential, since about 20 million tons of slag were produced annually in the United States, most of which had no commercial value.

Between 1908 and 1916, the OPR supervised or participated in the construction of several dozen experimental roads, ranging from earth-oil mixtures to Portland cement concrete and paving brick. These were inspected periodically and their service evaluated and correlated with the laboratory records of the materials that went into them. Eventually the OPR engineers drew up specifications for each type of construction based on their experiences with these experimental roads and the numerous object lesson roads. These specifications were published in bulletins, some of which went into five editions, and were widely used by counties, States and engineering colleges as references. In particular, the OPR’s specifications for bituminous road binders became the standards for the industry and were adopted by most of the State highway commissions.

Electric car on steel track at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition at Omaha in 1898.

The Dust Nuisance and Road Preservation

The light duty macadam and gravel roads constructed during the Good Roads Movement served their purpose very well until appreciable numbers of automobiles began to use them.[N 1] Many engineers, Page among them, were convinced that the solution to this troublesome problem lay in using something other than stone dust or clay as a binder for stone and gravel roads. Hot-laid asphalt paving had been used on city streets in Europe and the United States since the early 1870’s, but was considered far too expensive for country roads. However, liquid materials containing bitumen cement, such as petroleum, coke-oven tar and water-gas tar, were plentiful and cheap and seemed promising as dust layers.

An opportunity to test these materials came in 1905 when the Madison County Roads Association and the city engineer of Jackson, Tennessee, sought the OPR’s cooperation in experiments to determine the value of coal tar and petroleum oils for building dustless roads. Page agreed to participate by supplying expert supervision and the facilities of the OPR laboratory. The Tennessee experiments were moderately successful, and 3 years later, in 1908, the tar and residual petroleum oil (asphalt) treatments were pronounced “on the whole very satisfactory,” but the crude oil treatment had disappeared, leaving the roads as dusty as ever.[13]

The dust nuisance.

In the summer of 1907, the OPR joined with the Massachusetts Highway Commission to make experimental application of water-gas tar and coal tar on the main New York to Boston highway and also co-operated with Warren County and Bowling Green, Kentucky, to investigate the fitness of rock asphalt as a binder for macadam.

These projects all pointed to the need for a more systematic knowledge of bituminous products and methods for using them. To get some of this knowledge, the OPE, arranged a cooperative research project with Cornell University at Ithaca, N.Y., to test the relative value, under practically uniform conditions, of different bituminous road binders applied by different methods. As its contribution to the project, the OPR added two chemists to its laboratory staff and stepped up its testing and research on asphalts and tars.

The field tests showed that both the penetration method and the mixing method of making bituminous macadam surfaces gave good results. The laboratory studies were especially fruitful:

In succeeding years the dust abatement program was enlarged, until by 1916, the OPR was involved in experiments on 28 roads in 11 States and the District of Columbia. Gradually, the emphasis shifted from “dust prevention” to “road preservation,” and the building up of tar or asphalt wearing courses over macadam, slag or gravel bases. This led to the general adoption of bituminous surfaces wherever automobiles were an appreciable portion of the total traffic. Through its laboratory work the Office has been able to offer valuable advice in regard to specifications for bituminous road binders and in many instances to frame such specifications upon the request of various public bodies.

Many worthless road preparations have been and are at present being manufactured and sold to the public through ignorance on the part of both producer and consumer with regard to the requisite characteristics of such materials to meet local conditions. These materials are sold under trade names, and as a rule carry no valid guarantee of quality. Specifications for such materials are therefore needed for the protection of the public. . . . Some manufacturers have already followed the work of the Office along this line, and are either manufacturing materials in accordance with specifications of the Office or stand ready to do so upon request.[14]

In 1909 the science of producing Portland cement concrete was in its infancy. This early rotary mixer was used at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

The Office of Public Roads’ dust prevention and experimental roads programs were the training grounds for the small group of highway engineers and physical scientists who later laid the foundations of soil engineering and pavement design.

Dragging the Dirt Roads

Dirt roads will not stand up under traffic unless they are shaped and kept free of ruts so that water will shed quickly and not soak in and soften the roadbed. Even before the Civil War, some township supervisors were smoothing their roads by dragging them with “a stick of timber, shod with iron, and attached to its tongue or neap obliquely, so that it is drawn over the road ‘quartering,’ and throws all obstructions to one side.”[15]

Applying bitumen on a stretch of road at Cornell University in 1910.

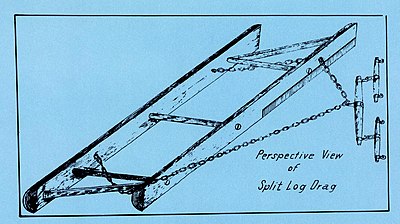

apart by struts and the lower edge of the front log was shod with a ¼-inch steel cutting plate. A hitching chain attached to the front log could be adjusted so that the drag would move earth to either side of the road as the device was pulled behind a team. This drag could be made on the farm for about $2.[16]

The King split-log drag was a surprisingly effective maintenance machine. After a little instruction and practice, an average farmer could easily drag 6 to 8 miles of road per day and could keep a well-graded dirt road in good shape for light traffic for as little as $8 per mile per year. The appearance of the King drag coincided with Director Page’s decision to place greater emphasis on earth and sand-clay roads in the object lesson road program, so Page decided to promote dragging as well. In 1906 he had King write a manual on how to make and use the split-log drag. This was published by the Department of Agriculture as a Farmer’s Bulletin, and thousands of copies were distributed. The OPR assigned experts to deliver lectures and make demonstrations in the use of the drag. A number of States passed “King Drag Laws” authorizing the township supervisors to contract with abutting farmers to drag the public roads.[17]

This activity, in a few years, brought about a remarkable improvement in the condition of the country dirt roads and brought home to the local supervisors, as nothing else had before, the importance of prompt and intelligent maintenance.

Experimental Maintenance

In 1911 the French roads were not only the best in the world, but were also the best maintained. Maintenance was strongly centralized and closely supervised; every road was divided into short segments of a few kilometers, each the full-time responsibility of a paid patrolman who lived nearby, usually within walking distance. Page wanted to try out the French system under American conditions, and in 1911 at his recommendation, the Secretary of Agriculture contracted with Alexandria County, Virginia, for a 2-year experimental maintenance project to include 8 miles of earth roads. Under this contract, the county supervisors agreed to shape up the roads and put them in good condition, after which the OPR hired a local farmer as a patrolman to maintain the roads under OPR supervision. The patrolman was paid $60 per month plus an extra $1 per day whenever he used his team for dragging.

The roads selected for the experiment—Columbia Pike and the Mount Vernon Road—were among the heaviest-traveled in the county,[N 1] yet the patrolman kept them in first-class condition most of the time at a cost of $95.77 per mile per year.[18] This, however, was far more than the average rural county was spending to maintain its roads. In the final analysis, this experiment demonstrated not so much the efficiency of the patrol system as the desirability of more durable surfaces for all but the very lightest-trafficked roads.

- ↑ One section near Fort Myer carried 173 wagons and 96 cavalry horses per day, plus a few runabouts.

The Washington-Atlanta Maintenance Demonstration Road

The Alexandria County experiment was the beginning of a major effort by the OPR to raise maintenance standards in the counties. By 1912, a decade of promotion by the good roads associations, the motorists, and the Office of Public Roads and others had trebled the funds available annually for roadbuilding. Hundreds of counties had issued bonds to finance road programs, and about half of the States had State-aid programs, some of which were financed by State bond issues.[N 1] Roads were improved with borrowed money faster than the supervisors could arrange to take care of them, and in this emergency, the counties turned to the OPE for advice and assistance.

To meet this demand, Page set up a Division of Maintenance in the OPR under Edwin W. James which embarked on an ambitious program of instruction and demonstration. James’ engineers studied the details of State maintenance in States that had effective highway departments and also in selected counties, some with good maintenance programs and some with poor ones. They also persuaded a number of strategically located counties with new bond-financed roads to introduce adequate maintenance on one selected demonstration road in each county, the work to be under OPR supervision.

Knowing who is responsible for the condition of the road and appealing to the pride of the patrolman.

The capstone of the maintenance program was a mammoth demonstration road, involving 49 counties in Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia, the purpose of which, in Page’s words, was “conducting an object lesson in road maintenance on a sufficient scale to attract general attention, and at the same time render the largest amount of assistance at the least relative cost to the Office of Public Roads . . .”[20] Under the plan adopted for this “Washington-Atlanta Highway,” a continuous route between these cities was traced over existing county roads, the combined length of which was 1,038 miles. The participating counties agreed first to put the selected roads in good condition and then to accept the supervision of an engineer assigned by the OPR who would approve all maintenance expenditures.

Removing the ridge with a drag after a cultivator has loosened the material.

The work began in the spring of 1914 with only 723 miles under the cooperative plan and three experienced engineers detailed by the OPR to supervise the work. The experiment continued until 1917 when the OPR had to withdraw its engineers for more urgent work. The success of the maintenance plan was attested by the fact that, from March 1915 through June 1916, a total of 876 miles of road had been under OPR supervision and “had not been closed to traffic at any point, even in the winter months,”[21] and by the adoption of the OPR maintenance methods by many other counties not on the Washington–Atlanta route.

Among these last was a group of 13 counties in North Carolina which joined with the State Highway Commission in 1916 to petition for OPR supervision over a proposed Central Highway from Morehead City to Statesville, about 338 miles. The OPR assigned two engineers to this project until the United States’ entry into the European war made it necessary to withdraw them.

The Problems of Road Management

The OPR’s four road construction demonstration teams could fill only a fraction of the requests for object lesson roads. However, in many cases what was needed was not so much a demonstration road as good advice from a road expert. After 1904 Page began detailing experienced engineers, upon request, as consultants to counties to get them started properly on their road programs. These assignments, each lasting from 2 days to a week, covered every conceivable aspect of road engineering and management and occupied most of the time of the OPR special agents.

As an example of this work, San Joaquin County, Cal., may be mentioned. At the request of the proper authorities an engineer was detailed to make a comprehensive study of all conditions affecting the highways of that county. About three months were required for this work, during which time his salary was paid by the Government and his local expenses by the community. The final report, besides containing a full and detailed description of the existing conditions, embodied also detailed recommendations for a system of improvements in road administration, construction, and maintenance within the reach of the people and which they have since adopted. A bond issue of about $1,800,000 was voted to provide the necessary revenues, and a system of roads is now under construction which will place San Joaquin County among the foremost counties of the State in the matter of transportation facilities.[22]

The “model systems” program was an instant success. By assigning as many engineers as he could spare from other work, Page in 10 years was able to assist 144 counties in 28 States to reorganize and modernize their road operations. Most of these counties sold bonds to finance a start on the programs recommended by the OPR advisers.

County patrolmen in New York were responsible for 2 to 8 miles of road and were paid $3 per day in 1914.

Bennington County, Vermont, carried the model system idea one step further. In 1912, 69 of the 74 road officials of the county, with the approval of the State Highway Commissioner, petitioned the OPR to detail an engineer for 1 year to supervise all road work in the county and its townships. Page assigned an engineer in 1913, who was in effect the County Engineer, in direct charge of all road work carried on in the county. This arrangement, one of the most extraordinary in U.S. highway history, lasted until December 1913. “The officials of Bennington County were so pleased with the results of this object-lesson supervision that they have since employed an engineer to take charge of the road work of the county.”[23]

The Shortage of Highway Engineers

The Bennington County experience pointed up one of the most serious problems of this period—the general lack of engineering expertise at the county level. Some critics asserted that, because of this lack, from one-quarter to one-third of all the money spent on the country roads was wasted. Most of this waste came about because the roads were originally poorly located or poorly drained, and these errors were perpetuated when the roads were later upgraded. Repeatedly, in its bulletins and expert advice, the OPR urged that the old locations be revised to reduce grades and unnecessary curvature, and to improve drainage before expensive bond-financed surfacing was undertaken. Such improvement required engineering study and advice.

Many, perhaps most, counties thought they were too poor to afford an engineer. Others didn’t really want one for fear he might lead them into expensive road schemes that would raise taxes. Still others clung to the ancient tradition of amateur supervision of inefficient statute labor. Those counties that wanted to hire engineers had difficulty finding them, since the supply of civil engineers with highway training was exceedingly small.

The shortage was so serious that Director Dodge in 1903 had recommended that Congress establish in Washington, in connection with the Office of Public Road Inquiries, a National School for Roadbuilding, similar to the famous School of Bridges and Roads which had trained French road engineers since 1747. This institution, as envisioned by Dodge, would be “. . . a post-graduate school, where graduates in civil engineering from the land-grant colleges could secure a thorough course in theoretical and practical road building. . . . The American school of road building should include a series of lectures by experts of this Office, and some practical work in the road-material laboratory and in connection with the object-lesson road work of the Office in different parts of the country.”[24] Most of the students would be employees of the States, counties and cities who would return to these agencies after completing their training.

This school was never established, but after he became Director, Page obtained Department approval for a training program under which a limited number of young civil engineering graduates, after taking competitive examinations, were appointed to the position of civil engineer student in the OPR, at a salary of $600 per year. These young men learned practical roadbuilding in the field with the OPR’s object lesson road teams. They received instruction in testing road materials in the laboratory and were detailed as assistants in the OPR’s other activities to learn by doing. After 1 year in the training program, they were eligible for promotion to junior highway engineer without further examination.[25]

Despite the small compensation, the OPR had no trouble recruiting all the civil engineer students it needed. Over a period of 10 years, some 70 engineers were hired, of whom about 36 resigned within a year of completing their training to accept positions with colleges, counties and State highway departments. Page accepted these losses philosophically:. . . the engineers after a few years’ training in the office are in great demand for State and county work. The practice of permitting these engineers to resign is detrimental in one sense to the service, in that the office is constantly losing some of its best men, but the benefits derived by the various States and counties through the distribution of trained men to all sections of the country are so great as to be a vindication of the wisdom of this project.[26]

Page also realized that his ability to expand the Federal good roads effort would depend on attracting additional experienced engineers to his staff. His first acquisition was Arthur N. Johnson, the able highway engineer of the Maryland Roads Commission.[N 1] Johnson agreed to take over the supervision of the OPR’s far flung field operations. Later, Page got Edwin W. James, who had supervised road work in the Philippines, to transfer to the OPR from the War Department. However, in the long run, the major source of recruitment for the OPR’s permanent force of engineers was the civil engineer student training program. Page’s foresight was forcefully demonstrated 12 years later when the trainees he had selected for this program became the backbone of the Bureau of Public Roads organization for administering the immense Federal-aid appropriations.

Director Page’s interest in the education and training of engineers went far beyond his own organization. In 1909 he had the OPR survey the status of highway engineering instruction in all the technical schools and colleges in the United States, and he furnished advisors to help the schools set up practical courses in highway design and construction. The OPR aided a number of schools to set up first-class testing laboratories, and whenever its agents and engineers could be spared from other work, they were detailed to lecture on highway engineering in the colleges.

Federal Roads on Federal Lands

Since the two agencies were in the same department of the Government, it was natural for the Forest Service to turn to the Office of Public Roads for help with its road problems, and the OPR was furnishing occasional advice on forest trails as early as 1905.[27]

However, it was not until 1913 that a formal arrangement was made for the OPR to handle road work in the national forests.[N 2] Congress in 1912 had required that 10 percent of the revenues from the national forests should be spent to construct roads and trails within these forests.[29] By the end of fiscal year 1912, $210,925 had accumulated in the forest road fund, and the Forest Service found that it needed expert advice on where and how to spend the money. The Chief Forester asked Director Page to assign highway engineers to inspect all the existing roads and to recommend how these should be improved and where others should be built. The OPR then assigned five engineers to this work, one for each of five forest districts.

About this time, the Secretary of the Interior also asked for assistance to help with the planning of roads in the national parks. Page responded by placing an engineer and a field survey party in Yosemite National Park during the summer of 1914 and promised to begin work in five other parks as soon as he could find the engineers.[N 3]

- ↑ Johnson resigned 2 years later to become chief engineer of the Illinois Highway Department, and he subsequently became one of the most distinguished American highway engineers and one of the founders of the science of traffic analysis.

- ↑ In 1910 the OPR, at the request of the Crater Lake Highway Commission, a private body, assigned a road expert to supervise the construction of a road through the Crater Lake National Forest to the Crater Lake National Park and to plan a system of roads and trails for the Park. This road was financed by county funds and private subscriptions and was not actually Forest Service work.[28]

- ↑ At this time, there was no National Park Service; each park superintendent reported directly to the Secretary of the Interior and did his own road work, except for Yellowstone where the roads were built by the Corps of Engineers. In 1914 there were 12 national parks.

To handle this sudden increase in workload, Director Page set up a Division of National Park and Forest Roads within the OPR and assigned responsibility for the Division to T. Warren Allen. The work in federally owned areas built up so rapidly that, by 1916, the OPR was maintaining 160 miles of road, constructing 170 miles and making surveys and plans for yet another 477 miles—a total program that was spread over 12 States and Alaska, and which exceeded the programs of a number of State highway departments. This far-flung program would soon receive a major boost from Congress in the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916.

Publicity Adds Momentum to the Good Roads Movement

Most of the OPR’s engineers were as much at home on the lecture platform as in the field or the laboratory. The special agents spent most of their time on such work, and they and the Washington Office staff were in great demand as speakers at road conventions and meetings of trade associations and professional groups. Director Page supplied lecturers only upon invitation and then only upon assurance that the meeting had been properly advertised and that the attendance would justify the expense. He was never able to satisfy the demand, even though he doubled and then trebled the number of men assigned to the work. In 1906 the OPR engineers gave about 100 lectures in 14 States. By 1912, 27 lecturers were giving 1,139 lectures which were heard by 208,472 persons in 37 States.[30]

To reach even more people, Page, in 1907, launched an information campaign directed at the rural population. Twenty-five hundred county newspapers co-operated by publishing short practical articles on road construction and maintenance written by the OPR staff. Through this program, Page estimated that he could reach up to 10 million people a year.[31][32]

Important as it was, the OPR publicity was only a small part of a nationwide outpouring of good roads propaganda. The magazine, Good Roads, founded by the League of American Wheelmen, was still the leading publication in the good roads field, but it had many competitors. In 1908 the American Automobile Association (AAA) launched the American Motorist to speak for the rapidly increasing number of automobile owners. Hardly a month passed without an article on good roads appearing in the influential Saturday Evening Post or in Harper’s Magazine, and between 1910 and 1915, it is safe to say that no national issue received greater coverage in the country and city newspapers.

Show Business in the Road Business

In 1908 Congress authorized a Government exhibit at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition and specifically provided that the Office of Public Roads should be represented. For its part of the exhibit, the OPR prepared a series of scale models, complete with miniature machinery, showing every aspect of roadbuilding. These were supplemented with a handbook, a series of moving pictures and stereopticon slides and a lecture on roads.

The Seattle exhibit of 1909 was so successful that the OPR made up several others like it which were shown at national expositions and fairs in 1910. These boosted the demand still further, so Page arranged to transfer a professional model maker from the Smithsonian Institution to augment the OPR’s effort. The models were loaned to various State fairs and expositions, which agreed to cover the cost of installation and transportation. The exhibits were accompanied by an OPR road expert to show the slides and give lectures. Between 1910 and 1917, the exhibits were shown at over 100 places and were seen by some 2½ million people.

In 1911 the Pennsylvania Railroad offered to provide a “Road Improvement Train” to carry the OPR exhibit throughout the State of Pennsylvania, and arrangements were made with the State Highway Department and the Pennsylvania State College to sponsor the tour. The train consisted of an exhibit car, a lecture car and two flat cars carrying full-sized crushers, rollers, graders and even split-log drags. The train stopped at 165 places during its 2-month tour. The crowds were so large in the larger towns that the lectures had to be held in court houses and opera houses. Over 53,000 people saw the exhibits and heard the lectures.[33]

Not to be outdone by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Southern and five other eastern and midwestern railroads petitioned the OPR to outfit Road Improvement Trains for them, and these took to the road in 1911 and 1912, carrying the good roads gospel to some 163,000 people in 650 towns. The last Good Roads Train in American history toured the State of Iowa in 1916.

The American Highway Association

By 1910 there were literally scores of organizations in the United States devoted to the promotion of good roads. A few of these were strong, effective, and national in scope. The American Automobile Association founded by the motorists in 1902 and the American Road Makers, bringing together State engineers, road contractors and road machinery manufacturers, were in this category. However, many of the good roads associations were primarily pressure groups whose purpose was to get improved roads by influencing legislation. Most of these had no dues-paying members but depended on commercial interests—railroads, materials producers, automobile manufacturers—for financial support.

The interior of the exhibit car of the Road Improvement Train.

Secretary of Agriculture Wilson and L. W. Page visiting the Road Improvement Train October 4, 1911.

This Association sponsored the First American Road Congress at Richmond, Virginia, in 1911 which passed strong resolutions recommending:[34]

- That Congress extend financial aid to the States to encourage them to build and maintain good roads.

- That no appropriation for road construction should ever be made without proper provision for maintenance afterward.

- That all States provide for State supervision of main highways through a State highway department, and that liberal financial assistance be given through State aid in the building and maintenance of such roads.

- That the work of construction and maintenance of all public highways of any locality or State should be under the direction of experienced highway engineers.

- That all the States enact laws providing for the employment of prison labor for the improvement of public highways.

- That, for safety of the public, all vehicles be required to display a lighted lamp at night, visible at least 200 feet ahead, and a red light visible from the rear.

- That the use of the muffler cut-out and the unnecessary use of horns and bells be forbidden in thickly settled sections.

- That slow-moving traffic be required to drive to the right so that faster vehicles may pass.

- That uniform speed regulations be adopted by all States, and the local authorities in cities, villages, and towns be prohibited from fixing local speed regulations.

- That officials responsible for bridges be required to inspect them periodically and post safe weight limits.

- That all roads be systematically placarded by sign boards giving directions and distances to towns and cities.

A plank bridge in South Carolina a half mile long and too narrow for two teams of horses to pass.

These resolutions were a complete and unambiguous statement of the principles that were to guide the American highway movement for the next 5 years.

In 1912 the Association shortened its name to American Highway Association and joined with the American Automobile Association to sponsor the Second American Road Congress. The Third and Fourth American Road Congresses followed in 1913 and 1914.

A number of State highway commissioners and chief engineers assumed very active roles in the American Highway Association, but most of the State men felt a need for an organization more specifically tailored to their needs. Such an organization, with membership restricted to the chief officials of the State highway departments and their staffs, was proposed by Virginia’s Commissioner of Highways, George P. Coleman, in January 1914. Page endorsed the idea, although he had hoped the State officials would organize within the framework of the American Highway Association, and in March 1914 he wrote to Mr. Coleman:It has become increasingly apparent to me during the past few years that some medium should be provided for bringing the heads of the various State Highway Departments and of this office into closer touch, for the consideration of questions of mutual interest. Some sort of organization is, to my mind, highly desirable, but I think the best results can only be obtained by limiting the membership strictly to official heads of departments and their immediate staff, thus making the organization strictly official and enabling full and frank consideration of questions, particularly those of a technical character untrammeled by commercialism or popular prejudices.[35]

With Page’s blessing, the formation of the new body was assured, and in December 1914 the American Association of State Highway Officials was organized “for the purpose of providing mutual cooperation and assistance to the State highway departments and the several States and the Federal Government, as well as for the discussion of legislative, economic and technical subjects pertaining to the administration of such departments.”[36]

One of the first acts of the newly formed association was to instruct the executive committee to prepare, for the consideration of Congress, a bill authorizing Federal aid to highways.

REFERENCES

- ↑ L. Page, The Selection of Materials for Macadam Roads, Proceedings of the Third American Road Congress (Detroit, Mich., Sept.–Oct. 1913), (Waverly Press, Baltimore, 1914) p. 170.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1919, pp. 34, 35.

- ↑ AASHO—The First Fifty Years, 1914–1964 (American Association of State Highway Officials, Washington, D.C., 1965) pp. 322–330.

- ↑ M. Eldridge, Public-Road Mileage, Revenues and Expenditures in the United States in 1904, Bulletin No. 32 (Office of Public Roads, Washington, D.C., 1907) pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1904, pp. 442, 443.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1909, p. 7.

- ↑ A. Rose, Historic American Highways—Public Roads of the Past (American Association of State Highway Officials, Washington, D.C., 1953) p. 92.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1905, pp. 427, 428.

- ↑ A. Rose, supra, note 7, p. 101.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1900, p. 287.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ 1971 Automobile Facts and Figures (Automobile Manufacturer’s Association, Detroit, 1971) p. 18.

- ↑ Office of Public Roads, Progress Reports of Experiments With Dust Preventives, Circular No. 89 (U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., 1908) p. 26.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1910, pp. 785, 786.

- ↑ W. Gillespie, A Manual of the Principles and Practice of Road-Making (A. S. Barnes, New York, 1871) p. 191.

- ↑ Office of Public Roads, The Road Drag and How It Is Used, Farmers’ Bulletin 597 (U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., 1914) p. 5.

- ↑ Kansas King Drag Bill, American Highways, Vol. 1, No. 10, Mar. 1907, p. 277.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1913, p. 9.

- ↑ Office of Public Roads, Public Road Mileage and Revenues in the United States, 1914, Bulletin No. 390 (U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.O., Jan. 12, 1917) p. 3.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1914, p. 6.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1916, p. 4.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 6, p. 27.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 20, p. 4.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1903, p. 332.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 8, pp. 434, 435.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1911, p. 28.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 8, p. 434.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 26, pp. 25, 26.

- ↑ Agricultural Appropriation Act of 1912 (37 Stat 288).

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1912, pp. 33, 34.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1907, pp. 22, 27.

- ↑ Bureau of Public Roads Annual Report, 1908, p. 6.

- ↑ BPR, supra, note 26, p. 42.

- ↑ American Association for Highway Improvement, Papers, Addresses, and Resolutions Before the American Road Congress (Richmond, Va., Nov. 1911) (Waverly Press, Baltimore, 1912) pp. 187–190.

- ↑ Supra, note 3, p. 50.

- ↑ Id. p. 52.