America's Highways 1776–1976: A History of the Federal-Aid Program/Part 2/Chapter 2

and

Economics

During the early days of the Republic, road management was amateur in most rural areas, and little money changed hands. The “statutory labor system” prevailed in most States. Under this arrangement, a “poll” or per-capita tax was usually levied. The rural citizen could pay it in cash or work it out either by laboring on the road himself or by hiring a substitute. If he provided a team and wagon, his credit for work done went up.

On the other hand, the average town or city dweller was not his own boss. Unlike the farmer, he could not arrange to set his own work aside to work a specified number of days on the road. Consequently, in most municipalities, the residents were taxed for the improvement, maintenance, and management of streets through property taxes, poll levies, or some other form of local tax. In the downtown areas of some of the larger places, businesses were taxed or they contributed voluntarily to the more highly improved streets.

During most of the 19th century, the chief source of funds for financing city and town streets was some form of real estate tax, which fell into three major classes:

- Property taxes levied against all real property for general purposes, the proceeds going into the general funds, from which appropriations were made for highway and other purposes.

- Property taxes levied against all real property specifically for street purposes.

- Special assessments of many kinds levied against specific parcels of real property for street purposes.

In many places, taxes were also imposed on various types of personal property, a portion or all of the proceeds being applied to street purposes.

The level of total annual expenditures on rural roads by all governmental agencies seldom, if ever, exceeded $75 million before 1904. By far the largest portion of this money came from property taxes, although a considerable amount also came from poll and “labor” taxes.

The so-called labor taxes were those imposts adopted to replace the requirement of a labor contribution. Actual labor contributions remained important in the building and upkeep of rural roads in some sections of the country for a long time. In 1914, 18 States reported considerable use of statutory labor. Although only four States, all in the South, reported the use of convict labor, it is known to have been more prevalent than this. The practice is still in use in a few areas today, but the cost of such labor is not eligible for Federal-aid reimbursement, although it can be used in the case of emergency construction following a disaster without disqualifying the entire project.

At the beginning of the automobile era, the street networks of the incorporated places in the United States were in a much higher state of development than were the rural roads. It has been estimated that in 1906, when annual expenditures on rural roads were at the $75 million level, expenditures on city and village streets were averaging about $300 million per year. Borrowing to finance large construction projects of all kinds, seldom resorted to in rural areas at that time, was a common practice in cities, es-pecially in the larger ones.

For highway purposes, borrowing in anticipation of future tax revenue was a local practice at first, but in 1893 Massachusetts became the first State government to contract debt to finance highways, although the territory of Idaho issued wagon road bonds as early as 1890. Other States, notably New York, California, Maryland, and Connecticut, soon followed the lead of Massachusetts, and State borrowing began a long period of steady increase.

The gas station represents the major source of highway financial income today. Will it be able to support future highway construction and maintenance?

Before 1914, county and local road bonds were concentrated in a relatively few States, exceeding $10 million in only seven: Ohio, Texas, Pennsylvania, Indiana, California, New Jersey, and Tennessee.

State Aid for Roadbuilding

State participation in the financing of road construction was an accomplished fact before the motor vehicle became a practical means of transportation. It began with a law enacted in New Jersey in 1891 providing for the appointment of Township Committees to inspect the roads in their townships annually and to develop a systematic improvement plan for them. The committees were empowered to employ engineers or other competent persons as consultants and to prepare plans and estimates. The financing plan obligated the State to pay one-third of the cost of improvements; adjacent property owners, one-tenth; and the county in which the improvement was made, the remaining 57 percent. To the county belonged the responsibility for road maintenance.

Middlesex County, the first to take advantage of the new plan, borrowed some $50,000 to $60,000 to pay the cost of three projects totaling nearly 11 miles. On December 27, 1892, the State paid its share of the construction cost, almost $21,000, “the first money paid by the State of New Jersey for improved roadways.”[1]

The State aid idea caught on rapidly, and, by the close of 1917, all 48 States had enacted such laws, though the patterns of aid varied widely from State to State, some at first providing only advice to the localities.

With the spread of State aid came the development of State highway systems. The first such system was established in Massachusetts in 1893 and the last in Mississippi in 1924. In the early days, State laws granted varying degrees of State control over these systems: Some States had none at all; others had full responsibility for them.

The highway-user tax, which was to become the great provider for large-scale highway development in this country, appeared inconspicuously, first in New York in 1901 with a registration fee of $1.00 per vehicle for regulatory purposes. In 1906, New Jersey established an annual license fee classified on the basis of vehicle horsepower. The rate was $3.00 for vehicles of less than 30 HP and $5.00 for those of 30 or more. The next year, Connecticut provided for a more steeply graduated scale of charges.

Thus, the user charge was in existence at the beginning of this century but not exploited as a source of significant amounts of revenue for highways. Its role as part of a system of motor-vehicle imposts dedicated to furnishing a consistent, dependable flow of revenue for long-term highway financing was not foreseen at this stage of highway development.

The highway-user tax derived from the registration of vehicles, in this case a 1905 Cadillac.

The Federal effort to improve rural post roads was rather disappointing since only 13 States participated in the project.

An Experiment in Federal Aid

The growing demand for highway improvement was reflected in the more than 60 bills introduced in the Congress in 1912 providing for some form of Federal aid for this purpose.[2] Activities leading toward development of a plan for nationwide Federal aid for highways first bore fruit in 1912, when Congress, in passing the Post Office Appropriations Act, took two steps: (1) It created an investigating committee to study the feasibility of providing Federal aidfor improving rural post roads, and (2) it appropriated $500,000 to aid the immediate building of such roads.

The Postmaster General and the Secretary of Agriculture were to administer the program jointly, and they were directed to select and improve certain roads for mail delivery. The States and their subdivisions were to pay two-thirds of the cost of the improvements and the Federal Government, one-third. The $500,000 in Federal funds for immediate construction was supplemented with $1.3 million of State and local funds.

Although the funds were provided through the Post Office Appropriation Act, direct responsibility for operating the program was assigned to the Office of Public Roads. For want of a better basis, the funds were apportioned equally among the States, about $10,000 to each. This approach failed miserably. Some States refused outright to participate, some were unable to do so because of constitutional and other limitations, and others simply did not respond to the offer.

Early use of trucks was limited to local industry because of poor road conditions and few interconnecting roads.

The Public Roads officials, together with cooperative State and local officials, then selected projects that they believed to be representative in such characteristics as topography, soil condition, and climate. The first project to be built under this Act extended for about 30 miles from Florence to Waterloo in Lauderdale County, Alabama. A total of 455 miles of road located in the 13 States that elected to take advantage of the program were improved under this arrangement, successfully demonstrating the possibilities of a Federal-State cooperative road improvement program.

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916

Two years before the landmark Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, revenue for rural roads and bridges had risen from $80 million in 1904 to $240 million, a threefold increase.[N 1] The number of motor vehicles registered had increased from 55,000 in 1904 to nearly 2 million in 1914.[3] But this increase is not as great as it appears to be, since it represents a larger number of States requiring vehicle registration in the later year—47 as compared with only 13 in 1904. Imposts on motor vehicles, rapidly growing in importance as a source of State income for highways, provided $12 million of the $75 million spent by the States for that purpose.

- ↑ In 1904 the Office of Public Roads began a policy of obtaining road mileage and revenue data at 5-year intervals. In 1904 the data were published in Bulletin No. 32 of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The data for the third such investigation (1914) are presented in HIGHWAY STATISTICS: SUMMARY TO 1965, issued by the Bureau of Public Roads in 1967, which is the general source of the financial and motor vehicle data in this chapter.

Of the almost 2.5 million miles of rural roads in1914, only 257,000 were surfaced and a mere 14,000 miles had a high type of surface:

| Bituminous | 10,500 miles |

| Brick | 1,600 miles |

| Concrete | 2,300 miles |

By 1916, 3.4 million autos were registered and 1 truck for every 14 autos. Roads were not equipped to meet the needs of this growing vehicle population. Probably because of the poor condition of most rural roads and their discontinuity, the use of trucks was limited almost entirely to cities and their close-in suburbs. Although trucks were beginning to be used for intercity transportation, this use was not yet economically significant and was largely restricted to the household moving industry.

Yet the potential of trucking was recognized; and farmers, railroads, and others joined the ranks of the auto owners and wheelmen (bicyclists) who were dissatisfied with the progress being made and who were pressing for better roads. One of their loudest complaints was about the lack of completed intercounty and interstate improved routes.

County and local authorities tended to improve those roads that were the objects of the greatest local pressure or were best suited to the needs of the local economy in narrow terms, with little regard for the requirements of the traffic going to and from other jurisdictions. Nor did the States usually make a serious effort to gear their road improvements to those of adjoining States.

A step forward in progress toward connected road systems, the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 contained some of the most important principles still in effect today. The Act reserved to the States the right to initiate projects and determine their characteristics and to perform the work directly or by contract. Completed projects were to be federally inspected and approved for reimbursement to the extent of 50 percent of the funds expended, not to exceed $10,000 a mile. The policy of the United States Government favoring a tax-supported highway system was expressed in a provision that “All roads constructed under the provision of this Act shall be free from tolls of all kinds.”

While the Act itself did not require that Federal aid be spent upon designated-system routes, the Bureau of Public Roads requested that each State highway department designate a limited system to which it would confine its Federal aid. Maintenance was made a State and local responsibility.

In recognition of the longer time span required for financing large capital improvements, funds were appropriated for a 5-year program and were apportioned among the States according to a formula based on area, population, and post road mileage. Thus, the eligibility of roads for improvement with Federal-aid money, adopted from the earlier post road Act, carried forward the justification of Federal aid on the basis of the use of roads for carrying, the mail, although the provision was so broad as to enable almost any rural road to qualify.

World War I and Its Aftermath

At the end of 1917, all 48 States had formed highway departments adequate to meet the requirements of the 1916 Act, and 26 States had submitted for approval 92 projects involving 948 miles of road, expected to cost about $5 million. With United States’ participation late in World War I came general economic dislocations because of the draining of man- power and materials to the war effort. By the 1918 fiscal year, all Federal-aid work was limited to projects essential to that effort. Even so, the required projects were such that the amonut of Federal-aid construction completed and under agreement continued to grow.

Following the Armistice on November 11, 1918, the public began to clamor for a speedup in the regular Federal-aid program. In 1919, Congress increased the appropriation for the period 1916–1921 from $75 million to $200 million. In spite of the handicaps of shortages and high costs of materials and labor, strikes, and unrest, the work accomplished during fiscal year 1920 exceeded by 25 percent all work done previously under the Federal Aid Road Act.

During the year, a survey was launched to obtain data needed to establish a classified system of highways. At the same time, Federal officials were cooperating with the War Department in selecting a system of highways of military importance.

Before the First World War, the military establishment exhibited little interest in trucks and truck transportation. In 1911 the Army began experimenting with their use. In 1912 it tried out trucks of 11 different makes in a cross-country operation from Washington, D.C., to Atlanta, Georgia, and thence to a camp near Sparta, Wisconsin. Only one vehicle, an all-wheel drive truck, finished the journey. The resulting Army report approved the use of trucks for field and supply purposes, but nothing came of it.

By this time, the Office of Public Roads had become interested in the possibilities of overland truck transportation. In 1911, the agency participated in the first coast-to-coast journey made by a truck by designating the driver as a special agent of the Office of Public Roads. Although the trip was accomplished in two entirely separate operations, it reached both coasts and demonstrated that trucks could negotiate the nearly impassable roads and rugged terrain.

World War I was the first “motorized” war, and thousands of trucks were built by American factories for military use. In 1919 a convoy of 20 Army trucks was sent from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco to further demonstrate the capability of such vehicles for wartime transportation. It took 56 days to complete the trip. One of the officers making the journey was Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower, who became greatly impressed with the possibilities of highway transportation. One of the significant roles of highways in freight movement has been to serve “as extenders and connectors for other transportation modes.” One highway extension of rail service, now called “piggyback,” began in a primitive form in the 19th century when circus wagons and wagons carrying farm produce and livestock were transported on flatcars, starting and finishing their journeys on their own wheels.

As now used, the term piggyback service means transporting cargo by both rail and highway, in or on highway trailers and principally in van-sized containers. Beginning in the 1920’s and extending into the 1930’s, extensive experimenting with piggyback service was carried on in an effort to increase the use of motor vehicles in moving freight by overcoming the limitations imposed by poor roads in disconnected systems. Conditions of the time did not support the effort, and it was left to the future.

Uncertainty and Crisis in the States

Failure of the Congress to enact a new highway bill before January 1921 precipitated a major financial crisis in most States. Having no assurance that a Federal-aid highway bill would be passed, the States had to cut back severely on work underway and contemplated. Contracts in progress were modified or canceled. Requests for bid proposals were withdrawn. Clearly a capital program of this magnitude required the regular commitment of funds over the relatively long period from planning to the completion of construction.

The States, seeking new ways to bolster their revenues, had begun to look to the motor vehicle as a potentially productive source. As motor vehicles became more numerous on the highways and their damaging effects on lightly constructed road surfaces became evident during the war period of 1917–1918, the practice of graduating registration fees with the weight or capacity of the vehicle grew until it had spread to all States. By 1917 all States required motor vehicles to be registered at fees averaging a little more than $7.00 per vehicle.

In 1919 the State of Oregon levied the first tax on the sale of fuel for motor vehicles. The tax was adopted by other States because it proved at least a rough measure of highway use, was relatively painless to the taxpayer, and easy for the State to administer. But in 1921 this tax, which later became the prime revenue producer for highways, brought in only $5 million, compared with $116 million for registration fees.

AASHO Recommendation

Shortcomings of the 1916 Act began to be evident by 1919, and the annual report of the Bureau of Public Roads for the 1920 fiscal year contained recommendations made by the American Association of State Highway Officials for modifying some of the financial provisions of the law:

- Federal appropriations should be at least $100 million a year in order to carry out the program.

- The Federal-State 50-50 matching ratio should be modified to increase the Federal share in States where more than 10 percent of the area was public lands.

- The application of Federal aid should be restricted to those roads that would expedite completion of a national highway system.

- Federal appropriations for forest roads should be continued for 10 years at the level of $10 million a year.

The corner of Dearborn and Randolph Streets in Chicago, 1910.

The Federal Highway Act of 1921 provided for only a 1-year continuation of the cooperative Federal–State financing plan by appropriating $75 million for the 1922 fiscal year. But the next year, Congress began the practice of authorizing Federal aid for succeeding periods of 2 or 3 years. These funds were then apportioned to the States in accordance with the previously existing formula with two modifications: one for small States and the other for the large public land States.

For small States, which were receiving virtually meaningless amounts of aid (for example, less than $25,000 apiece for Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont in 1917), a floor of at least one-half of 1 percent of the total apportionment was established. For the large western States, whose extensive areas of untaxable federally owned land put them at a serious disadvantage, the remedy was to increase the Federal share of highway funds above 50 percent in proportion to the ratio of public lands to the total area of the State. The areas within national forests, parks, and monuments were excluded from the calculation.

To insure that Federal funds would be spent on roads of more than strictly local importance, the Act required that all Federal-aid funds be expended on a primary system of highways limited to 7 percent of the State’s total highway mileage on November 9, 1921. This interconnected system included two classes of highways: (1) Primary or interstate highways, comprising 3⁄7 of the system, and (2) secondary or intercounty highways, comprising the remainder. No more than 60 percent of the funds apportioned were to be expended on the primary or interstate highways.

City residents began to benefit from the highway improvement program long before the expenditure of Federal-aid highway funds on municipal streets wa authorized. By focusing attention upon the improvement of intercity and interstate routes, the creation of the Federal-aid primary system under the 1921 Act stimulated more travel over greater distances than had been possible before.

Urban automobile owners began to venture beyond the city limits on “joy rides,” and commercial and intercity trucking developed. On the other hand, although farm-to-market trucking of agricultural commodities became common in many areas, the horse and wagon was still an important factor in such movements.

Highways a Local Program

The highway program was still essentially a local one in 1921, financed largely from property taxes and general-fund revenues and concentrated on county and local roads. If the work-relief expenditures of the thirties are excluded, the estimated capital outlay of $337 million for county and local roads in 1921 was not equaled until the early fifties. At the same time, almost three-fourths ($771 million) of the more than $1 billion of total current revenue (i.e., exclusive of bond proceeds) available for road and street purposes was obtained from county and local sources. The Federal and State governments furnished the remaining $285 million, of which $123 million (43 percent) came from State imposts on motor vehicles.

Bond proceeds of $353 million increased the current (exclusive of bond receipts) highway funds available by about one-third. The county and rural local governments borrowed about 57 percent of this sum ($202 million) and the States the remainder. Borrowing by municipalities was not reported.

Increasing Role of Credit Financing

It was common practice to issue highway bonds secured by a general pledge of the taxing power of the issuing authority. These general obligation or full faith bonds are still predominant among the obligations issued to finance toll-free capital projects.

The same corner in 1966.

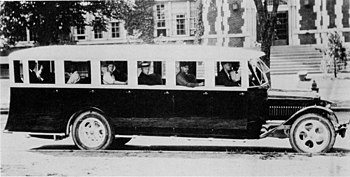

A 1922 deluxe coach manufactured by the Superior Motor Coach Body Company.

During the period from 1921 to 1930, bond proceeds contributed from 25 to 40 percent of all State construction funds. This was the first great period of accelerated bond financing. Illinois, for example, authorized bond issues totaling $160 million; Missouri, $135 million; and North Carolina, $115 million. In these States, and others with similar programs, bond issues formed the bulk of highway construction funds during the decade.

A number of States that did not or, because of constitutional limitations, could not issue bonds did not hesitate to make use of the borrowing power of the counties, townships, and road districts. These units in numerous States either borrowed to build roads that later became State highways or supplied bond proceeds to the State highway departments.

Beginning in the 1920’s, many States undertook to reimburse the counties for these contributions to State highway systems. These obligations usually took one of two forms: (1) An agreement between the State and its local governments whereby the State would reimburse the local governments in annual amounts for costs incurred initially in building roads that later become part of the State systems or (2) an agreement whereby the State would pay to its counties an annual amount equal to the interest and principal on local highway bonds issued for such purposes. The security for this type of obligation was somewhat obscure except when the State had funded or refunded the obligation from the proceeds of its own bond issues.

The practice of transferring funds between levels of government complicates the pattern of highway finance in other ways. The States not only provide financial aid to counties and cities, but they spend money directly on county roads and city streets. There are also arrangements whereby one unit of government performs certain services (maintenance, for example) for another and is reimbursed for the cost of the services.

Most of the Federal expenditures for highways in 1921 were, of course, in the form of aid to the States, amounting to $78 million. The States also received $33 million from county and local rural governments and transferred $22 million to them—a net increase of $11 million in State funds and a corresponding decrease in the county and local funds available for expenditure on roads.

The Federal Highway Act of 1921 confirmed the Federal Government’s policy against tolls on federally aided facilities expressed in the 1916 Act. But large bridges and other crossing facilities, because of their semi-monopoly position and their costliness, had long been widely accepted as suitable for toll-revenue financing. The use of revenue bonds payable solely from the earnings of the facility (tolls) began with the Port of New York Authority bond issues in 1926.

In 1927 Federal policy with respect to tolls was modified by the Oldfield Act (now 23 U.S.C. 129(a)), which allowed the States or their instrumentalities to use Federal funds to construct or acquire toll bridges, provided that net revenues would be applied to the capital costs of the facility or the retirement of its debt and provided that the facility would be toll free upon retirement of its outstanding indebtedness. This Act had the effect of discouraging the construction of privately owned facilities and did not lead to any significant amount of toll bridge construction.

From War to Depression

The period following passage of the Federal Highway Act of 1921 was one of considerable accomplishment, as improvements on the designated Federal-aid system moved forward. Annual Federal authorizations remained at $75 million through 1930 and the onset of the Great Depression.

Total expenditure for highways by all levels of government grew rapidly, reaching $2.5 billion by 1930. State income for highway purposes had risen steadily since 1920. The yield of State motor fuel taxes constituted only 3 percent of State and local imposts on motor vehicles in 1921. By 1926 they totaled $188 million, which was 40 percent of user-tax collections, though still well below the $258 million received from registration fees.

In 1929, the first year in which all the States and the District of Columbia levied the motor fuel tax, its yield exceeded that of registration fees. By 1931 it produced $538 million, nearly three times the 1926 yield and close to twice the income from registration fees of $298 million.

In 1923, when 37 States imposed a motor fuel tax, the average rate was under 2 cents a gallon. In 1929 it averaged approximately 3.7 cents.

A new fee was added to the user-tax family in the twenties. Vehicle-operator and chauffeur licensing began in most States in the early part of the decade. In 1925 the States obtained nearly $10 million from this fee, which is not considered a prime source of revenue for road purposes.

As the decade of the thirties opened, the Depression triggered by the 1929 stock market crash was beginning to be felt in highway financing, but there was a delayed response to economic conditions so that, for a time, the pattern of highway finance continued very much as it had before. The Federal-aid program had been moving forward at a rapid rate. Federal aid for highways of $273 million in 1931 was nearly three times the 1921 figure. Together, Federal and State funds were providing half of all current income available for roads and streets. The equivalent of most of the Federal-aid funds received by the States was passed on to the counties and local governments. Only $50 million of these funds was spent by the States themselves.

State taxes on motor vehicles and their use were now a major element in the tax structure. Totaling $848 million in 1931, they were 93 percent of all State revenue for highways obtained from State sources. They provided nearly seven times their 1921 yield and constituted about 36 percent of the total of $2.3 billion available in that year for highway and street expenditure by all levels of government. State bond proceeds added another $351 million to the available State funds.

On the expenditure side, the total by all levels of government began to decline sharply in 1930 until it reached a low level of about $1.7 billion in 1933. Although declining, State current expenditures (excluding debt retirement) of $1 billion in 1931 were still more than 2½ times their 1921 level. On the income side, on the other hand, average State registration fees and related imposts began to decline only slightly after 1931, largely because of the adoption of graduated fee schedules lowering the rates for certain types of vehicles, notably passenger cars and light trucks.

For county and local roads, expenditures from regular highway funds had reached $700 million in 1930, nearly $100 million more than they were in 1921. Expenditures for city and village streets showed much greater growth, rising from $337 million to a high point (if Federal work-relief expenditures are omitted) of about $800 million. Taken together, these 1930 expenditures by the counties and localities, rural and urban, were more than 1½ times their 1921 level. During the 10-year period since 1921, a change in emphasis had taken place in the financing of local roads and streets. In 1930 the counties and local rural units of government were spending more to maintain and administer their roads and to pay interest on the debt incurred for highways than they were spending for new construction. Expenditure for construction by the urban governments exceeded those of the rural governments by close to $200 million, a foretaste of the effects of the great population movement to the cities.

Failure of the Property Tax

Motor vehicle imposts were relatively unaffected by the Depression. The major problem in highway finance arose from the failure of the property tax to fulfill its customary role in support of the highway function, which had been a major recipient of property tax income in most States. The municipalities were almost totally dependent on the property tax for road and street funds, and the counties and local rural governments only a little less so.

As income from farming and other sources declined, unemployment soared, and prices (especially farm prices) skidded downward, taxpayers began to default on their mortgage and tax payments. Delinquency rates rose rapidly, and mortgage foreclosures and tax sales became common.

State laws were enacted providing for increased leniency toward tax delinquents. Limits were placed on tax rates, the levy of taxes on property for certain purposes was sometimes forbidden, and homeowner and other exemptions were introduced.

Laying a new stone block surface at East 23d and Broadway in New York City in the late 1920’s.

Much automobile travel was evident in the 1930’s despite the Depression, thus, the need for new autos to replace old ones.

In 1931, the States faced difficulty in matching their Federal-aid apportionments. To ease the effects of the Depression, annual Federal highway authorizations were increased to $205 million in 1931, reduced somewhat to $125 million in 1932, and increased again to $229 million in 1933. But the lack of matching funds was only partly the result of these large increases above the $75 million a year previously authorized. Nor did it arise from declining State revenues from motor vehicle imposts, since these revenues declined very little at any time during the Depression. Rather, it stemmed from the large sums used by the States to replace local revenues from property taxes in financing local roads and city and village streets. Moreover, substantial amounts were diverted from highways to meet the rising demand for expenditures for other purposes.

Many States took action to provide tax relief by reducing or eliminating property taxes as a source of revenue for highways. In four States (Delaware, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia), responsibility for administering and financing all county and local rural roads was transferred to the States, except that in Virginia the counties were allowed the option of retaining control of their highways. Following the transfers, local property taxes for highways were customarily reserved for servicing debt already outstanding and sometimes for bridge construction.

Indiana was representative of States that left secondary and local roads under local control but provided for the transfer of State motor-vehicle user taxes to the local jurisdictions for the support of roads. In these States, imposition of property taxes for highways was usually forbidden except for bond service. Most of the remaining States adopted a middle course, transferring some roads from local to State responsibility or providing increased State aid for secondary or local roads.

Emergency Federal Aid

In an act passed on December 30, 1930, Congress advanced $80 million to the States for matching regular Federal-aid apportionments. As conditions worsened, the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 made a further advance of $120 million. It also provided for 1-percent additions to the Federal-aid highway systems that were originally limited by the Federal Highway Act of 1921 to 7 percent of total State highway mileage, as these systems were completed according to standards acceptable to the Bureau of Public Roads.

Unemployment grew to crisis proportions, and Congress was forced to turn from the regular Federal-aid program to other types of financing, emphasizing projects that would provide for as much direct labor as possible. Thus, the regular Federal-aid authorizations were replaced with emergency appropriations. The Federal Government made available a total of $1 billion of such funds for the fiscal years 1934–1936, far more than ever before for a like period of time.

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, while not primarily a highway bill, included several provisions affecting the financing of highways. The President was authorized to make grants of not less than $400 million to State highway departments to provide for the emergency construction of highways. The use of these funds did not carry with it the customary restrictions on the use of Federal-aid highway funds. The funds were to be available without matching by the States. They could be used for projects on the urban extensions of Federal-aid system routes; for paying as much as 100 percent of the costs of preliminary engineering; for projects associated with highway safety, such as building footpaths or eliminating highway-railroad grade crossings; and for construction on secondary and feeder roads off the Federal-aid system. Seven-eighths of these emergency funds were to be apportioned according to the regular Federal-aid formula and the remainder on the basis of population alone. The Act did not specify how the funds were to be allocated to the highway systems. An administrative decision was made to allocate about 50 percent to the rural Federal-aid system, 25 percent to its urban extensions, and 25 percent to secondary and feeder roads.

Some $95 million of the authorized $400 million went to highway projects on secondary or feeder roads not then on the approved system of Federal-aid highways but which were either part of State highway systems or important local highways leading to shipping points on roads that would permit the extension of existing transportation facilities. This was the first major Federal action directed towards secondary or farm-to-market roads.[4]

The Hayden-Cartwright Act of 1934 authorized a highway appropriation of $200 million to be apportioned to the States immediately according to the revised formula of the National Industrial Recovery Act. No less than 25 percent of the apportionment to any State was to be applied to secondary or feeder roads.

The States were relieved from repayment through deductions from future Federal-aid apportionments previously advanced for emergency unemployment relief. Matching by the States was not required, and the money could be used to pay for such preconstruction expenses as surveys and the preparation of plans.

The effect of the 1934 Act was to incorporate as a matter of continuing Federal-aid highway policy the provisions for using Federal funds to improve secondary and feeder roads and to eliminate such traffic hazards as railroad-highway grade crossings. The Act also provided for withholding sums up to one-third of their subsequent Federal-aid highway apportionments from States using motor-vehicle revenue for nonhighway purposes, except in those instances provided for by State laws in force at the time the Hayden-Cartwright Act was passed. This was the genesis of many State so-called “antidiversion” amendments.

State governments have often dedicated income from particular sources to particular purposes. This practice, which is embodied in State constitutions and statutes, has the effect of removing “earmarked” revenues from the regular annual or biennial review of the legislature. Carried to an extreme, it allows no flexibility in applying income to the governmental services determined to be necessary at any given time, so that a case could be—and was—made for the point of view that the special commitment of funds to highway purposes had no valid significance—that all governmental revenues should be general revenues and all expenses should be defrayed out of general funds.

While it was generally acknowledged that the nonhighway purposes to which highway-user revenues had been directed were, for the most part, essential functions for which money must be obtained from some source, nevertheless the antidiversionists pointed to the fact that the State highway-user tax schedules had been predicated on the concept that in paying these taxes the highway user was contributing his due share to the support of the highway system. Highway-user taxes being measured by the requirements for highway expenditures, the product of these taxes, it was argued, should be used for the purpose that determines their magnitude.

Historically, the highway function in this country had always partaken of the nature of a public utility, with aspects both of a private-enterprise and a governmental activity. Before the coming of the motor vehicle, local taxpayers could not meet the demand for land transportation over long distances, and it was left to private capital to provide these facilities. For a while, the pricing mechanism was tolls, and the user-tax principle was partially developed during the period of the early toll roads. These roads were soon put out of business by the railroads, roads once more becoming a local governmental function. Highway-user taxes, then, could with justification be linked to the benefits received from the service to which they were dedicated, inasmuch as they provided an indirect pricing of the benefits of highway use.

With the development of the road-user tax structure and its growing importance as a source of highway funds during the 1930’s, a number of States followed the lead of New Mexico, the first State to issue general obligation bonds secured by a specific pledge of road-user tax revenue. Bonds backed by this type of security proved to be a more attractive investment than bonds secured by the general taxing power of the State.

Although no regular Federal-aid authorizations were made for the fiscal years 1934 or 1935, Federal funds continued to be authorized for forest highways (begun in 1917) and public lands highways (begun in 1931). Other highway funds not administered by the Bureau of Public Roads were made available through the National Park Service, the Forest Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Allocations for Indian reservation roads were made for the first time in 1933.

Although 1934 was a mid-Depression year, the indicators of highway use were on the upswing. Motor vehicle registrations were already close to full recovery.

Present patterns of automobile use were fairly well established at that time. More automobile trips were made for earning a living than for any other purpose, and most auto trips were within a radius of less than 10 miles from home. Average annual automobile travel was generally least in the rural agricultural areas and highest in middle-sized cities.

As motor vehicle ownership increased and private automobile travel became more convenient and dependable, other available passenger service began to dwindle and, in some cases, essentially disappear. Among the casualties—mainly after 1930—were the electric interurbans, local railroad passenger service, and local commuter bus and trolley service. By the late 1930’s, many communities were left with no public passenger transportation service at all.

Moving people and goods: the trolley line, the highway, the canal, and the railroad. By late 1930’s, the trolley lines and the canals had become casualties of the transport war between highways and railroads.

The transportation of goods by highway, on the other hand, was becoming increasingly important economically, so much so that by the late 1930’s the railroads, beginning to view intercity truck transportation as a competitive threat, called for a study of truck taxation. In 1936, the first year such calculations were attempted by the Bureau of Public Roads, the average truck was estimated to have been driven about 10,000 miles a year, and total travel of all trucks was estimated at 41 billion vehicle-miles.

Special fees and taxes had begun to be levied in connection with registration fees on for-hire carriers of persons and property. By the mid-thirties, such imposts were in effect generally in the States, although they were not great revenue producers. Their importance lay in their usefulness as a means of regulation and of applying concepts of equity to the tax schedules.

The 1933 low point of $1.7 billion in total expenditures for highways was followed by an erratic increase, which peaked at almost $2.7 billion in 1938. Then the Federal emergency funds began to run out. But the expenditures from funds normally available for highways continued a gradual upward trend until World War II stringencies began to force a reduction. Federal work-relief expenditures, although continued through 1942, reached a maximum in 1938, when the amount spent on county and local rural roads reached $389 million and on city and village streets, $367 million.

The late 1930’s saw what may be said to be the beginning of the modern toll road movement with the construction of the Pennsylvania Turnpike from 1937 to 1939. The State turned to this method of financing because of insufficient funds to improve existing roads to adequate standards. But the turnpike was not financed as a wholly self-supporting facility. Federal Public Works Administration grants totaling $295 million were supplemented by $40.8 million of bonds sold to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The turnpike suffered badly because of wartime restrictions in the 1940’s, and it operated at a loss most of the time until the end of the war.

Although the total governmental debt for highways included such large revenue bond issues as those for the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the San Francisco Bay Bridge, and the Port of New York Authority’s bridge and tunnel program, the period of the 1930’s produced slightly diminished State highway borrowing. The dominance of Federal-aid funds during this period of depression and recovery reduced the relative contribution of bond proceeds to about 20 percent of the funds used to finance highways. But the reliance on borrowing shifted from the local governments to the State. In 1926 State highway bond issues exceeded those of county and rural local governments for the first time and, with several exceptions, have annually dominated the highway bond market.

The Federal Government’s anti-toll policy was once again written into the statutes with the passage in 1937 of a law authorizing Federal-aid funds to be used for freeing toll bridges on the Federal-aid system. It authorized the payment of Federal money up to 50 percent of the cost of labor and materials actually used in the construction of any toll bridge built after 1927 on the Federal-aid system. In return, the recipients had to agree to remove the tolls.

At the close of the 1930’s, highways had not fully recovered from the effects of the Depression. World War II was raging, and the possibility of an end to United States neutrality was on the horizon. Highway Development During World War II

The Federal Highway Act of 1940 became law more than a year before the Pearl Harbor incident made the United States an active belligerent. The Act provided that, on request of the Secretaries of War and Navy or the head of any other official national defense agency and by order of the Federal Works Administrator, Federal-aid highway funds previously authorized could be used, without matching, to pay for preliminary engineering and for supervising the construction of projects essential to the national defense.

The decade of the 1940’s was marked by two contrasting developments: (1) The cessation of normal highway construction during World War II followed by (2) accelerated construction expenditure accompanied by an increase in borrowing for highway purposes after the war. At the outset, the Nation was entering a period of wartime economic boom that hastened what might otherwise have been a long, slow pull out of the Depression. But the boom found materials, equipment, and labor for normal civilian purposes in short supply.

In 1941, 78,000 miles of highway were designated as the strategic network developed in cooperation with the War Department and used in selecting high-priority projects for construction. Approximately 20 percent of the mileage in this network was found to be seriously inadequate, and the proportion was found to be even higher on other essential roads, such as those providing access to war industries, ammunition depots, and military establishments.

The Defense Highway Act of 1941 appropriated funds for construction on the strategic network, to be apportioned according to the standard formula but with State participation limited to not more than 25 percent of the project cost. Funds were authorized, without apportionment, for projects on access roads, these funds to be available with or without State matching and usable for purchasing right-of-way and for off-street parking.

Policy for the conservation of critical materials called for (1) deferring all nonessential highway construction that would consume large amounts of such materials; (2) substituting less critical materials, where possible; and (3) deferring construction through maintenance operations. These practices plus the inability of governments to stretch the available resources in materials and manpower to cover routine maintenance added to the large volume of unmet highway needs that had been accumulating since the early 1930’s.

Highway expenditures, which had not yet returned to their pre-Depression level, again began to decline. County and local governments, both rural and urban, were receiving from 45 to 47 percent less from their own sources than they had in 1930. Though in 1941 State-collected highway revenues were 36 percent above their 1931 level and the States had stepped up their aid to rural local governments, still the funds available for local roads were substantially below the 1931 figure. Construction expenditures for county and rural local roads reached a low point of $72 million in 1944.

In 1943 and 1944, total expenditures on city and village streets reached their lowest level ($321 million) since 1920. The principal cause was the war-imposed curtailment of construction, which totaled only $71 million in 1943. Expenditures at the Federal and State levels also declined until the close of World War II.

The 1943 Highway Act amending the Defense Highway Act of 1941 served as a bridge between wartime and postwar programs. It extended the emergency funding programs of the 1941 Act and amended the definition of construction in order to continue the use of Federal-aid highway funds for the purchase of right-of-way. It also broadened the provisions related to reimbursing the States and other governments for road damage resulting from national defense and other war-related activities.

Executive Order 8989 of December 18, 1941, created the Office of Defense Transport (ODT) as a wartime agency to assure continued essential operations and maximum use of domestic transport facilities for the successful prosecution of the war. The ODT’s Highway Transport Division, supervising motor transportation, pursued the objective of the order through issuance of orders governing full loading, delivery schedules, and interchange of freight. It also pressed for allocations of fuel, tires, and other critical items in short supply to enable domestic truck transportation to perform its service.

Postwar Problems

When the war ended in 1945, highway agencies entered the postwar period under conditions of great difficulty. It had become apparent that during the period preceding the war, insufficient effort was put into the construction and maintenance of roads and streets to insure that the quality and condition of the highway plant would keep pace with the demands of traffic. The agencies were therefore faced with the necessity of a widespread modernization and reconditioning of highway facilities, both rural and urban. The problem was complicated by the fact that construction and maintenance costs, which rose very materially during the war period, become inflated with the general rise in prices that followed.

The Federal Government’s grand plan of attack on postwar highway problems was embodied in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, which added some important new provisions:

- A new National System of Interstate Highways, not to exceed 40,000 miles in length, was authorized.

- A specific system of secondary Federal-aid highways, not limited in size, was provided for.

- Recognition was given for the first time to a system of urban extensions of rural Federal-aid highways.

- Authorizations were made by systems in a 45-30-25 ratio for primary, secondary, and urban (ABC) systems for each of 3 successive years. No funds were specifically authorized for the Interstate System.

The apportionment formula adopted for the Primary System was continued, giving equal weight to the three factors of population, area, and post road mileage. The formula adopted for the Secondary System was the same except that rural instead of total population was used. The urban apportionment was based on the sole factor of population of municipalities and other urban areas of 5,000 or more.

The Act added to the law a provision authorizing the States to use 10 percent of apportioned Federal funds without matching to eliminate hazards of highway-railway crossings on the Federal-aid systems. The railroads were to contribute 10 percent of the construction cost of those projects benefiting them.

Postwar Taxation for Highways

During the 1940’s, the States strove to improve their revenue positions by increasing the tax rates on motor fuel. In 1947, 8 States raised their rates, and the average rate for all States rose from 4.16 to 4.25 cents a gallon. During 1949, 13 States increased their rates, bringing the average State rate to 4.52 cents.

Regardless of what originally precipitated the adoption of user taxes, no carefully worked out theory preceded their adoption. The theoretical foundation was built after the tax framework was erected. The structure of highway taxes was an evolution brought about over a long time by balancing the demands of conflicting interests with the necessities for the development and support of highways.

The Rio Grande Gorge Bridge, located near Taos, N. Mex. carries the highway over the Rio Grande 650 feet below. Originally, Federal aid was limited to $10,000 per mile for bridges under 20 feet and 50 percent of the cost for bridges over 20 feet. Because bridges are so costly to build, many are financed through bonds or as toll facilities.

Part of the pressure that led to the development of a more organized body of highway tax theory during this period was produced by a changed attitude on the part of the railroad industry. The industry had been a supporter of highway development in the beginning, viewing road improvements as a means of providing better feeders to their lines. At that time they paid taxes without complaint. But as highways encouraged long-distance freight movement by truck, they began to realize that they were facing serious competition. Fearful of the results of growing diversion of traffic, they became active critics of both the operating and the business practices of highway carriers and of the extent to which such carriers paid taxes to support the government expenditures made in their behalf, i.e., the extent of the public subsidy of the motor carrier industry.

The framework of highway tax theory is founded on the principle that taxation for the support of highways should be assessed in proportion to benefits received. There had been nearly universal acceptance of the concept that the provision of highway facilities serves three major interests finding a parallel in three principal sources of highway revenue:

- The interest of access to land and improvements, a service indispensable to personal, family, and business activity (taxes on land).

- The public interest or general welfare, represented by the use of roads in such public activities as national defense, police and fire protection, access to schools, and conservation of natural resources (appropriations from general funds).

- The interest of the motor-vehicle user in providing facilities upon which the private automobile may be used in recreational, social, and personal business activities and the commercial vehicle may be operated in gainful pursuits (motor-vehicle user taxes).

The fact that the owners and occupants of adjacent and nearby property received special benefits from highway improvements had long been recognized by the common practice of imposing special assessments for such improvement. Benefits to property throughout a given area were recognized in taxes upon property in general, and the general property tax was also recognized as representing community benefits as well as those directly assignable to the land.

The fact that the benefit principle was firmly imbedded in the earlier period of highway financing probably paved the way for the adoption of motor-vehicle registration fees and gasoline taxes as means of taxing the motor-vehicle owner for benefits received. Thus, the gasoline tax, during the period when it was being eagerly adopted by State after State, was commonly described as a “metered tax,” and one State, New Hampshire, continued to call its gasoline tax the “road toll.”

The further fact that the rapidly developing use of motor vehicles was bringing about the necessity for greater and greater highway expenditures was also a very potent factor in popularizing the imposition of user taxes. Thus the concepts that underlie the later investigations of the highway tax problem had a natural evolution in the history of highway development.

After WW II it was evident that greater highway expenditures would be needed to cope with the volume of traffic. Highway taxation had to be determined on an equitable assignment of tax responsibility among beneficiary groups in proportion to the benefits received.

The central problem of highway taxation was one of determining an equitable assignment of tax responsibility among various beneficiary groups in proportion to the benefits received or highway costs occasioned by each of these groups. The problem divided itself into two parts: (1) The allocation of the highway tax burden among the major classes of beneficiaries of highway expenditures and (2) once the equitable portion assignable to motor-vehicle users was determined, the allocation of the motor-vehicle user share among vehicles of different sizes, weights, and classes of use. A number of methods with supporting concepts were devised for making these determinations and were used by many States for revising their tax schedules.

Vehicle Registrations and Fuel Consumption

Largely because of the effects of motor fuel rationing, motor vehicle registrations declined only 13 percent during World War II, compared with decreases of 37 and 33 percent, respectively, in travel and fuel consumption. Until the 1940’s the rate of growth in fuel consumption per vehicle closely paralleled the rate in total fuel consumption. But after 1946, the rate per vehicle rose more slowly than that of total consumption, because of the growing density of motor vehicle ownership. While ownership of more than one car increases the total miles of driving, the increase is not proportionate to the number of vehicles owned. Thus, a household with one car averaging 12,000 miles of driving annually does not double that mileage by buying a second car but may increase it to perhaps 15,000 or 18,000 miles. Fuel consumption in 1946 averaged about 746 gallons per vehicle per year.[5]

New Directions in Borrowing

The venerable custom of borrowing money and paying interest on it has its motivation in the simple economic fact that money in hand always has more value than an equal amount in prospect. The existence of a net advantage to be derived from the use of funds now rather than in the future is the criterion justifying public borrowing. The most favorable condition for credit financing is that of a truly accelerated program contemplating a relatively short period of abnormally high capital outlay, during which the highway plant progresses rapidly toward a condition of adequacy. A subsequent lull in construction activity, during which the need for replacements accumulates very slowly, provides the opportunity for retirement of the bonds.

Conditions following the end of the war were ripe for such a program. The need for greatly increased expenditures to permit reaching a standard of adequacy was recognized in most States. The demands for highway capital funds for financing particular urgently needed facilities or statewide “catch-up” programs encouraged the circumvention of constitutional barriers to State-created debt, either by the more direct but less frequent method of amendment or referendum or by the speedier and, hence, more popular device of the nonguaranteed bond that does not have recourse to the full taxing power of the issuing government and does not require approval of the electorate.

Because they command higher interest rates, non-guaranteed bonds almost always carry with them a higher cost to the public. But the additional cost may be a justifiable premium to pay for avoiding the consequences and delays of seeking voter approval.

During the 5-year period 1946–1950, the States, including special State authorities and commissions, issued over $1 billion in highway bonds (not including refunding issues); the counties and other rural local units issued $429 million; and the cities and other incorporated places issued $635 million. The combined total was $2.2 billion of a total outstanding debt at the end of 1950 of about $4.5 billion.

The debt issued during this period tended to be concentrated along the Eastern Seaboard, where so much of the population, industry, and heavy traffic volume were also concentrated. These States accounted for 80 percent of the total.

The toll road movement was the most dramatic development in highway financing, particularly in credit financing, in the years immediately following World War II. The success of the Pennsylvania Turnpike with the public, despite its war-induced financial difficulties, stimulated a boom in toll road construction. These roads proved to be feasible where the traffic potential was high and where the parallel free roads were either in poor condition as to grades, curves, or surfaces or where they were inadequate to serve the traffic in the corridor.

The growth in toll road bond financing in the period 1946–1951 was striking. To the $54 million of toll road bonds outstanding at the beginning of the period, issues totaling $449 million were added. Redemptions during the period were a slim $12 million, leaving $491 million outstanding at the end of 1951.

The postwar period was one of variety and experimentation in the credit financing of highways, and by no means all of the toll roads were financed by the issue of revenue bonds payable solely from the earnings of the facility. The first fully self-supporting issue of toll road revenue bonds was marketed in 1946 by the Maine Turnpike Authority. Elsewhere, general obligation bonds were sometimes issued, and the building of the 15-mile New Hampshire Turnpike was financed from the proceeds of 90-day renewable notes purchased by Boston banks. By this device of short-term financing, not extensively employed by the States in financing highway capital expenditures, the State of New Hampshire was able to save in interest expense by drawing down funds only as needed.

Bridge Tolls

In general, the Federal Government continued to look upon toll financing with disfavor. In the late 1940’s, a Federal statute was enacted to encourage the removal of bridge tolls. The General Bridge Act of 1946 required that, within 20 years of construction or acquisition, tolls be removed from all bridges subject to the Act (i.e., interstate bridges). Bridges wholly inside a State or those between the United States and foreign countries were not covered by this legislation.

In 1948 the Act was amended to extend the period for removing tolls to 30 years. Meantime, the 1937 law authorizing the use of Federal funds to free toll bridges on the Federal-aid system expired. During the time it was in force (1937–1947), nearly $9 million had been spent to free 30 bridges in five States.

While the number of toll facilities owned by counties and local governments is relatively small, in the 1940’s toll charges provided a greater portion of the income from county and local imposts upon highway users than any other single impost. Most of the income derived from these toll charges was spent for highway purposes, chiefly maintenance and operation of the facilities and retirement of the debt incurred when they were built.

The Federal Role in Borrowing

In the wake of the rapid development of toll roads, the Federal Government had not abandoned its belief in toll-free highways. Accordingly, a section of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1950 (section 122, title 23, U.S. Code) provided that any State or local government that issued bonds and used the proceeds to accelerate construction of toll-free facilities on the Federal-aid Interstate or Primary Systems or on extensions of Federal-aid systems within urban areas might apply authorized Federal funds to retire such bonds. Federal funds might not be claimed for the Federal-Aid Secondary System, either in reimbursement of interest payments or for bond proceeds expended on that system.

The Act made the following stipulations:

- The proceeds of the bonds qualifying under the law must have actually been expended in the construction of Federal-aid systems.

- The construction must have been completed in accordance with plans and specifications approved in advance by the Bureau of Public Roads.

- Payments could not exceed the pro rata Federal share specified by law.

- Payments must be made from funds authorized by the Congress.

This program was in no sense a Federal lending device; rather, it had the effect of postponing reimbursement of the Federal share of authorized Federal-aid projects. It had two advantages to the States:

- Programs involving Federal-aid work could be planned and financed in advance of the availability of Federal funds.

- Federal funds might be claimed at times and in amounts determined by the maturity schedule of the bond issue, reducing the demand for current State tax revenue for debt service during the time the bonds were maturing.

Financial Status in 1951

By 1951, the postwar pattern of highway financing was well established, except for the changes to come with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The States were providing nearly two-thirds of the funds (exclusive of borrowings) applied to the highway program (about $2.7 billion), and motor-vehicle user taxes, including tolls, accounted for about 97 percent of these funds.

Contributions from Federal general funds were $492 million. This amount was about $60 million less than was available from this source in 1941, but the 1941 amount had come largely from special unemployment relief appropriations rather than from regular sources of highway aid.

Funds provided by rural and urban local governments had recovered to approximately the level of 1931: $483 million in local revenues of the rural governments and $585 million in local municipal revenues.

Bond issues for road and street purposes during 1951 totaled $794 million, of which $535 million was State borrowings. Beginning in 1948, the States resorted to heavy borrowing to expedite their accelerated highway improvement programs.

By 1951, the program for catching up on deferred maintenance and capital outlay was well underway. Total capital outlay on all systems, which bottomed out at $362 million in 1944, had reached a level of $2.5 billion and was climbing rapidly. Maintenance expenditures had recovered from a wartime low of $640 million to a total of $1.6 billion in 1951. Total highway expenditures were $4.6 billion.

Federal-Aid Funds and the 1956 Highway Legislation

Between 1944 and 1956, Federal legislation dictated few major policy changes. The first Interstate System construction was specifically authorized in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952, which provided for apportionment of $25 million on the basis of a 50-50 Federal–State matching ratio in each of the fiscal years 1954 and 1955. These authorizations were increased to $175 million each year for fiscal 1956 and 1957 by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954, which also raised the Federal share of project costs to 60 percent.

The twin 1956 Acts—the Federal-Aid Highway Act and the Highway Revenue Act—are a major landmark in the highway history of the United States. This legislation broke with tradition and established some new principles:

- It authorized and provided for financing an entire highway network, now designated the National System of Interstate and Defense Hghways.

- It departed from the traditional 50-50 sharing of project costs and the fixed formula for apportionment.

- It established a Highway Trust Fund fed from the proceeds of Federal excise taxes on motor-vehicle users, which thus directly linked to highway expenditures.

The Highway Revenue Act of 1956 continued the biennial authorizations of Federal-aid primary, secondary, and urban highways (popularly termed the ABC program). But the policy of authorizing Federal aid to the States for highways for 1- to 3-year periods was augmented by one of authorizing funds for a long-range program to complete the Interstate Highway System.

A total of $27 billion was authorized for the Interstate System, to be apportioned on the basis of 90–10 percent Federal–State shares of project costs. For the first 3 years of the program, apportionments among the States were to be made on the basis of total population (one-half). After this, the funds were to be apportioned according to the proportion that the estimated cost in each State bore to the total cost of completing the entire System.

It was recognized that some States might be willing and able, with current revenue or bond proceeds, to build their portions of the Interstate System faster than the annual Federal-aid apportionment would permit. The 1956 Act therefore provided for “advance” construction by arranging for later reimbursement to the State for the Federal share of the project costs from apportionments of succeeding years. Federal aid was also made available for the cost of relocating utilities displaced by federally aided highway construction.

In linking Federal excise taxes on highway users and Federal aid for highways, this Act sought to accomplish three objectives: To finance the long-range Federal-aid program, to provide the revenue wholly from user-tax revenues, and to preserve the program on a pay-as-you-go basis. Although automotive excise taxes of one type or another have been levied by the Federal Government since 1917, except for the period 1928–1932, no part of the proceeds of these taxes was earmarked for highways before 1956. Before that date, Federal aid for highways was appropriated from the General Fund of the Treasury and was not related to the income from taxes on motor vehicles or their operation.

In the Highway Revenue Act of 1956, Congress provided revenues for a program of highway expenditures on the Interstate and other Federal-aid highway systems. The mechanism by which this was done was to create a Highway Trust Fund into which were directed the proceeds of certain existing excise taxes on motor vehicles and automotive products and certain additional taxes imposed by the Act itself.

In particular, the Federal gasoline tax was increased from 2 to 3 cents and became the principal source of revenue of the Highway Trust Fund. In order to provide more revenues, certain changes were made by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1959, including an increase in the motor- fuel tax from 3 to 4 cents a gallon.

The creation of the Highway Trust Fund resulted in the direction of the greater part of the Federal automotive tax proceeds into that fund but not all of them. Remaining as General Fund revenues were the proceeds of the 10-percent Federal excise tax on automobiles and motorcycles and the 8-percent tax on parts and accessories. There is also a tax of 6 cents per gallon on lubricating oil. Since only about 60 percent of the lubricating oil is estimated to be consumed in highway vehicles, this tax was ordinarily not as closely associated with motor vehicles and their use as are the taxes on motor vehicles, tires and tread rubber, and motor fuels.

Although nearly all of the income of the Highway Trust Fund was derived from excise taxes paid by highway users, certain amounts were derived from nonhighway sources. The largest such amounts were receipts from taxes paid on gasoline used in aircraft, motorboats, and industrial use, but in this case 2 of the 4 cents per gallon tax, if claimed, was subject to refund to the taxpayer. The proceeds of the tax on tires used off the highway (5 cents per pound) was also placed in the Trust Fund, as was the small amount of income obtained from automotive excise taxes paid by the Department of Defense on behalf of highway-type vehicles used entirely in off-highway service. Although such vehicles were exempt from motor-fuel taxes, payment of taxes on the purchase of trucks, buses, trailers, tires, and inner tubes was required.

Because Federal-aid expenditures for highways were now directly related to the income from certain highway user taxes, the equity of tax payments in relation to benefits and the highway costs occasioned by various types of vehicles had to be considered. The 1956 Act, therefore, called for a highway cost allocation study similar to those conducted by the States but on a nationwide basis in order to bring about “an equitable distribution of the tax burden among various classes of persons using the Federal-aid highways or otherwise deriving benefit from such highways.”

By the end of the 1957 fiscal year, approximately $1.5 billion had been deposited in the Trust Fund, of which $3 million came from interest earned on investments and the remainder from Federal automotive excise taxes. From this total, nearly $966 million was disbursed for work on the Interstate and ABC programs, but there was a balance of obligations of apportioned highway funds of nearly $2 billion.

The 1956 Act also marked the first exercise of Federal limitations on commercial vehicle sizes and weights. It established maximum width and weight limitations on the Interstate Highway System to protect the Federal investment in this system and to prevent overstressing of bridges for safety purposes.

Toll Roads and the Interstate System

Inclusion of toll facilities on the Interstate System has been a major issue since the accelerated program was authorized in 1956. Of the 40,000 miles of highways approved for the System in the early 1950’s, 1,100 were toll facilities. A 1955 report by the President’s Advisory Committee on a National Highway Program indicated that about 5,000 miles of toll roads planned, being constructed, or in actual operation in 23 States would either parallel or coincide with the proposed Interstate Highway System.

The Highway Act of 1956 adopted a Bureau of Public Roads’ recommendation for incorporating toll roads into the Interstate Highway System. The prohibition against the use of Federal funds for constructing toll facilities was modified only to the extent of permitting their use on the approaches to toll roads, with two provisos:

- If the only use of the access road was to serve as an approach to a toll road, the toll road must be made toll free upon retirement of the outstanding debt.

- Satisfactory alternate free routes for bypassing the toll sections must be available.

Seven toll facilities have received Interstate funds on condition that the tolls be removed upon retirement of the debt:

Indiana Toll Road

Northern Illinois Toll Highway

Kentucky Turnpike[N 1]

Maine Turnpike

New York Thruway

Ohio Turnpike

Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike

Because of the legal complexities and contractual requirements under which the various toll facilities were established, a feasible means of freeing those on the Interstate Highway System remains one of the paramount unresolved issues. Many of the toll facilities operating as part of the Interstate System have outstanding debt secured by toll revenues with redemption dates beyond the year 2000. In a number of cases, statutory provisions require tolls on such facilities to be collected indefinitely, beyond the time when the toll-secured debt is retired.

- ↑ Tolls were removed from the Kentucky Turnpike on June 30, 1975.

In some cases, debt proceeds and revenues related to both highway (including Interstate) and nonhighway facilities have been commingled and are not readily identifiable. Toll revenues are primarily used for operating the toll facilities and retiring the outstanding indebtedness but are also used in some instances for other public services (more often in the case of toll bridges than toll roads). Thus, the loss of revenue for other purposes has to be taken into account.

Since 1956, the Federal Highway Administration has refused to approve the location of free routes on the Interstate System in at least three cases where the routes would parallel toll facilities determined to be adequate for traffic needs until 1975, where the financial structure of the toll facilities was in danger of being adversely affected.

Bond Financing in the 1950’s

Toll revenue bond financing was employed by 29 of the 39 borrowing States during the decade of the 1950’s, and in six States—California, Illinois, Indiana, Oklahoma, Texas, and Virginia—it was the only major type of bond financing used. Although revenue bond financing occupied a position of prominence, road-user tax bonds and other limited obligations evidenced a most significant increase. The seven Northern and Eastern States that issued $200 million or more of general and limited obligation bonds accounted for nearly two-thirds of all such bonds issued.

Municipal highway debt showed a much faster rate of growth than that of the counties and other rural local governments. If the debt outstanding at the beginning of 1950 is assigned a value of 100, the comparative volume of municipal debt outstanding at the end of 1960 would be 215.5 and rural local debt, 148. The more pervasive demand for credit financing by the municipalities was partly caused by the relatively greater State financial assistance to rural governmental units and also to the rapid growth of metropolitan areas and urban traffic volumes during the 1950’s. General obligation bonds were the predominant type of local issues.

The Public Corporation Device

Although the device was not new even in the highway field, beginning in the 1940’s and continuing through the 1950’s, public corporations (authorities) came into extensive use. The features that distinguish the authority device are not always clear-cut. For example, a number of State highway departments—and local governments too—directly finance and operate toll projects. But this is not the primary function of a highway public works department. The term “authority” is generally reserved for (1) those instrumentalities whose primary responsibility is the financing of highway facilities with revenue or limited obligation bonds, for which specific revenues are pledged, and (2) those that do not rely upon general tax support or that themselves have the power to levy taxes.