Archaeological Journal/Volume 6/Memoir on Roman Remains and Villas Discovered at Ickleton and Chesterford, in the Course of Recent Excavations

The investigation of that important period in the early history of Great Britain, the invasion and establishment of the Romans, has recently been pursued with increasing zeal and interest. Much had been effected by antiquaries of the last century, in tracing out the great outline, but many evidences remained by which the results of that extraordinary crisis in our history might be more clearly shown and appreciated. It did not suffice to mark with careful accuracy the great military works, the entrenchments and high-ways, monuments of extended conquest; a field of more interesting- inquiry was to be sought in the scattered vestiges of Roman occupation, serving to show the powerful influence of the introduction of foreign arts and manners. It is no idle labour to trace out the results issuing from that hostile ambition or cupidity which had tempted the Romans to our shores, not merely tending to civilisation in social life, and advancement in public institutions, but to the extension of the light of Christian faith to these remote islands.[1]

In the absence of written records regarding the Romans in Britain, the historian must call the antiquary to his aid. It is by the detailed investigations which are still in progress, and the intelligent care with which those researches are directed, that the antiquities of this period acquire an interest, in details relating to the arts and usages of private life, which the dry recitals of Horsley or Stukeley may have failed to excite. It were much to be desired that all these materials could be united and arranged; and it is gratifying to hear that the publication of an extended "Britannia Romana" has been undertaken in earnest. The antiquaries of the Northern Marches, neighbouring to the great works of Hadrian and Severus, may best carry out this useful project; but we feel assured, that when they collect the fruits of research in other parts of England, not only Woodchester or Bignor, but later discoveries at Chesterford, Durobrivæ and Caerleon, will meet with the attention which they merit.In a recent notice of the researches of Mr. Neville on the borders of Cambridgeshire and Essex, and the site of ICIANI, as recorded in two interesting contributions to Archaeological literature from his pen,[2] we adverted to further discoveries of Roman remains at Chesterford, then in progress. Of these, Mr. Neville has from time to time kindly communicated particulars and plans, with various interesting fictilia and antiquities, exhibited at the meetings of the Institute. We have now the gratification of acknowledging his kind liberality in enabling us to place before our readers the following detailed report of these discoveries; and cordial thanks are not less due for thus permitting us to anticipate their publication, which we hope may be expected from his own hand, than for his generous donation to the Institute of the illustrations by which the present memoir is accompanied.

About the middle of August, 1848, the attention of Mr. Neville was drawn to a field at Ickleton, in the tenancy of Mr. Samuel Jonas, who had noticed that in certain places the crops every year were "burned." This was so marked last May, that a son of Mr. Jonas was enabled to make a rough plan of the spot. The field is called "Church Field," and is situated about a quarter of a mile from the village. On the 21st August, Mr. Neville ascertained, by the use of a crowbar, the existence of foundations, on the spots pointed out, and the next day his men commenced the work of disinterment. Walls were rapidly laid bare, and rooms uncovered. Several fragments of tiles and a red tessera were quickly found, giving rise to the idea that the building was Roman. This notion was soon confirmed by the discovery of various fragments of "Samian" ware, third brass coins (twenty or thirty in number); and, lastly, before a fortnight's work, a hypocaust was found, with numerous piers formed of square tiles in situ, and buried in soot and light ashes. Under one of the piers, when it was removed, was found a first brass coin of Hadrian. The excavations were continued, and the entire vestiges of a villa were gradually uncovered, of the arrangement and dimensions of which a correct notion may be formed from the ground-plan, which we are enabled to submit to our readers. A second hypocaust was found, with its piers of brick in situ, and some flue-tiles remaining also in their original position. Three adjacent rooms, connected with the main building only by a single wall, running diagonally from the S.W. angle, were likewise discovered, as shown in the annexed plan, the result of a detailed survey by Mr. J. C. Buckler. Mr. Neville has favoured us also with a valuable description of the architectural features of these remains, communicated by Mr. Buckler.

In this villa were found numerous fragments of different kinds of fictile ware, including the moiety of a "Samian" dish, of a common type, and a fragment of the rim of a vessel of dark-coloured ware, upon which were traced with a sharp point the letters—CAMICIBIBVN . . . . very probably, according to the reading proposed by Mr. Neville—ex hoc amici bibunt. About thirty coins of the Lower Empire were found; numerous tesseræ of various sizes for Mosaic pavement, chiefly of large size and coarse material, but some were small and of finer quality, of white, red, and dingy black, or blue colour, as if a pavement of superior description had at some period existed here. There were also many tiles, with various scorings, but none bearing the potter's stamp, or any legionary mark: some of them had been impressed, whilst in a soft state, with feet-marks, two or three being prints of dogs' feet, one that of a human foot, and another of a cloven hoof, like the foot of a deer. Two glass beads, and upwards of twenty pins, needles and styli of bronze and bone, were found. Amongst the foundations there were brought to light the bones of not less than six infants, aged from two to four months.

In one of the three detached rooms were found two bronze keys, and at a little distance to the south of these rooms was found a deep hole filled with fragments of fresco paintings, which had apparently been purposely broken up and thrown there. Mr. Neville has preserved in his museum at Audley End numerous specimens of different patterns, some of which are of elegant design, and strikingly contrasted colours, as bright as if the painting were freshly executed. Besides numerous ornaments composed of flowers, trellis-work, &c., Fragments of Castor Ware. | ||

| | ||

ANTIQUITIES DISCOVERED IN THE RUINS OF ROMAN BUILDINGS AT ICKLETON AND CHESTERFORD.

PLAN OF A COLUMNAR BUILDING, DISCOVERED BY THE HON. RICHARD NEVILLE, AT ICKLETON.

Remains of South Eastern Angle.

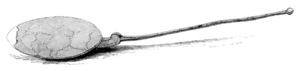

After this villa had been fully bared, trenches were made in various parts, to ascertain if there were any other foundations adjacent to it, and further remains were discovered about thirty or forty yards to the S.E. of the villa. When these foundations were laid open, they represented the curious building, which has been variously denominated by those who have examined the remains, as Temple, Church, and Basilica.[3] Of this singular structure a ground-plan is given, from Mr. Buckler's measurements and design. A detailed description by Mr. Buckler is also subjoined, with a representation of the eastern side of the north-eastern angle, a good specimen of Roman walling. The walls are composed of flints mixed with chalk, the angle being composed of seven courses of wall-tiles (now remaining) laid upon a kind of footing. The tiles average 112 inches in thickness; the joints 114 inches. In the progress of excavating this building, there were found a celt, of simple form, of green-stone, a material of remarkably tough and hard quality; two bone instruments for marking pottery; two bone combs; two bone pins of elegant shape; a massive bronze bracelet, in the shape of a serpent; a second brass coin of Hadrian; and about twelve third brass, of different emperors. By Mr. Neville's liberality, we are enabled to give representations of one of the combs, which is of unusual form, and of the bronze armilla. The bones of six infants were also found in this building.

The original destination of this building is a point of difficult decision, which must be left to future research. Mr. Nee has received from an intelligent correspondent, resident near the spot, the following remarks, which his kindness permits us to give, in connexion with this inquiry:—

"In consequence of your discovery of the temple with the bases of its columns, I write you a few lines to set forth more clearly what I believe I once hinted. Just to the right of the gate as you go out, is the smallest possible dip in the turnpike road, seemingly too trifling to obtain a name, but being no doubt the remains of a rather deeper one, filled up by the way-wardens. This is known by the name of Church Bottom; upon which I will suggest the following remarks:—

1. It is entirely remote from Ickleton Church, of which you can only see thence the top of the steeple in the distance. 2. Ickleton Church is, in its present site, of remote antiquity; its west door and nave being (as I believe) in the oldest style of Norman or semicircular architecture. 3. The Church Bottom is as closely contiguous to your Temple or columnar Building, as a public road can well be to a rural church, allowing to the latter any yard or purlieus at all. 4. I believe the coinage found is mostly of, or after, the reign of Constantine.

Therefore, I can hardly refrain from inferring as follows:—That your columnar Building was used (whether constructed or not) as a Christian Church. That it was still standing when the East-Anglian Saxons became possessed of these parts. And that, upon their conversion to Christianity, it resumed its office of a church for this parish, and was succeeded by the Norman building, now standing in another place. Because, if the ancient Temple Church of our Roman predecessors had been swept away finally, or finally desecrated in the fifth or sixth century, the vernacular name, Church Bottom, would be completely unaccountable.

You will perceive a corollary to all this. The dip or bottom is much too trivial to have been observable upon land; and it must have been named in reference to the road. From which you ascertain that there was a regular road or way precisely in the direction of the existing road, at the time when the Roman building was still in use as a church."

The villa, which has lately been laid bare by Mr. Neville at Chesterford, is the ancient site formerly mentioned by Stukeley under the name of "Templi Umbra," in the Borough Field, as shown in his plan of the Station, given in his "Itinerary,"[4] and the sketch engraved in the "Reliquiæ Galeanæ."

The account of this supposed Temple, and of the survey of Chesterford, in July, 1719, given by Stukeley in his "Itinerarium Curiosum," does not differ essentially from the observations contained in his letter addressed to Roger Gale, immediately after his visit. As this last, however, apparently less known to those who have written on the remains of this Station, has the additional value of having been the record of recent impressions, it may not be uninteresting to cite the passage. Speaking of Chesterford Magna, and the great Icknild-street there crossing the Cam, Stukeley says:—"I had the pleasure to walk round an old Roman city, there, upon the walls, which are still visible above ground; the London road goes fifty yards upon them, and the Crown Inn stands upon their foundations. Thither I summoned some of the country people, and, over a pot and pipe, fished out Anglo-Roman Pottery, probably fabricated at Castor, with Ornaments in relief and painted.

Discovered in a Romnn villa at Chesterford, Essex, October, 1848.

| |

| |

The land, where the site of the Temple was traced by Stukeley, being this winter in such a state that excavation would occasion no injury, Mr. Neville, with the permission of Mr. Owen Edwards, to whom the field belongs, commenced operations immediately after he had finished at Ickleton. Stukeley's measurements were compared, and foundations were found very nearly on the spot which he described; on being uncovered, they proved to be the remains of a structure bearing no resemblance to a Temple, but simply a Roman dwelling-house. The excavation was commenced on Oct. 10, 1848, and quickly showed the Roman character of the remains: innumerable fragments of various kinds of Anglo- Roman pottery were discovered, including two small vases of the peculiar embossed ware, supposed to have been fabricated in the potteries of Castor, according to the valuable researches of the late Mr. Artis.[6] (See Woodcuts). Also, a specimen of "Samian," ornamented with the ivy-leaf pattern in high relief, and a very singular vase of pale red-coloured ware, not lustrous, of peculiar form, and having on each side a ring attached, as imitative handles, resembling in its general fashion the curious vessel found at Felmingham, Norfolk, with a remarkable assemblage of Roman remains.[7] There were also found an olla of brown-coloured ware, impressed apparently by three fingers, whilst the clay was soft, possibly a mark of capacity; (See Woodcut); and a large two-handled amphora, similar to one figured in Mr. Neville's "Antiqua Explorata," Pl. V. Numerous bronze and bone pins were found, with tesseræ, fragments of tiles, a bronze armilla of slender fabric, and a curious object of bronze, resembling the pendant, or tag, of a girdle, but fitted to a kind of sheath, the use of which it is difficult to explain. A similar relic of bronze is preserved in the York Museum, found with Roman remains; and another, deprived of its sheath, is given in Mr. Artis' Durobrivæ, Pl. XLI., Fig. 10. A small bronze spoon, was also discovered. The ground-plan of this building, taken by Mr. Buckler, and illustrated by his observations, will supply satisfactory information in regard to this example of the habitations of Roman times.

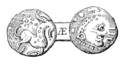

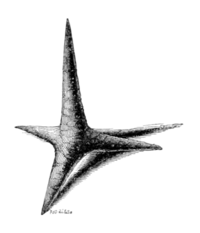

Of the fictile vessels, some were found within, and others just outside the walls. Besides the relics now enumerated, there was afterwards found, in breaking up and removing the foundation walls, a diminutive brass coin, much defaced by age and decay, an undescribed type of the British period, and attributed by some antiquaries to Cunobelin. On the obverse appears to be represented the head of an animal (?) On the reverse, slightly convex, a goat, (?) with a flower or star of ten points over it. No similar type is found in the British Museum, or amongst the coins of the earliest age, of which a series is represented in the recently published "Monumenta Historica Britannica." A small ring-fibula of bronze, set with four fictitious gems of blue paste (one of them lost), was also discovered, of which a figure, of the original size, is given. It is difficult to conceive how similar ornaments of this diminutive size, which occur not only amongst Roman, but Medieval remains, could have been used. Various implements, formed of iron, much decayed with rust, were also found amongst these remains, including some objects of great rarity, namely, caltraps, formed of four points radiating, each in a different plane, from a common centre, as shown in the woodcut. It has been supposed that these were used, as in Roman races at the present time, where the horses run without riders, to stimulate their speed, being attached to pendant straps in place of the calcar. This is possible; it is certain that caltraps were used in Roman times to annoy cavalry. Vegetius relates how advantageously tribuli were scattered by the Romans, when assailed by the scythed chariots of Antiochus and Mithridates. His description of them precisely corresponds with the specimens before us. Valerius Maximus calls them murices. One, supposed to be Roman, is figured by Caylus, Recueil, t. iv. Pl. XCVIII. Another in the Encycl. Method.In order to ascertain whether any other buildings had existed near the site of this villa, Mr. Neville caused trenches to be cut in every direction around it, but no trace of foundation appeared, nor any of the pillars of which Stukeley makes mention. A single fragment of a pillar, with its base, was found in the villa, measuring about three feet in height. Amongst the foundations of this structure, again, were discovered the bones of three infants, and one male skeleton. The occurrence of the remains of children of very early age, found, as it has been stated, in or near the various ancient buildings investigated by Mr. Neville, is a fact not undeserving of special notice. Juvenal makes allusion to the usage of interring infants without cremation:—

"Terra clauditur infans,

Et minor igne rogi."—Sat. xv. 139.

This is confirmed by the observation of Pliny, who, speaking of the usual period of dentition,—"editis (infantibus) primores septimo mense gigni dentes, priusquam in supera fere parte, haud dubium est," remarks subsequently—"hominem priusquam genito dente cremari, mos gentium non est." Hist. Nat. lib. vii. c. 16; and ibid. c. 54, "aiunt mortuos infentes in suggrundariis condi solere." The eaves of the house were termed suggrundæ, or subgrundia; so that the practice appears to have been to inter infant remains closely adjacent to the external wall of the dwelling. Thus also Fulgentius remarks,—" Subgrundaria antiqui dicebant sepulcra infantium, qui necdum quadraginta dies implessent; quia nec busta dici poterant, quia ossa, quæ comburentur, non erant; nec tanta cadaveris immanitas, qua locus tumesceret. Unde Rutilius Geminus in Astyanacte ait: Melius subgrundarium misero quæreres, quam sepulcrum." (Facciol. in v.) It is striking to find, after the lapse of so many centuries, the deposit of these fragile remains, so fully in accordance with the tradition of this ancient custom, and corroborative, if indeed such evidence were requisite, of the Roman origin of these buildings.[8]

The following observations on these vestiges of ancient architecture, and peculiarities of their construction, have been most kindly placed at our disposal by Mr. Neville. They comprise the results of a careful examination by Mr. J. C. Buckler, and illustrate, in a very interesting manner, the character of the discoveries which we have endeavoured to describe:—

"As the remains of one of the residences are at a considerable distance from those of the other, it may, perhaps, be useful to precede their description by a few observations upon the general appearance of a tract of ground, which, although now devoted to agricultural purposes, seems to have been once distinguished by habitations of a superior character, the relics of which have appeared wherever the ground has been opened.

This interesting district is situated nearly midway between the public road from Newport to Bourne Bridge, on the south, and the village of Ickleton towards the north; the road to the last place forming the eastern boundary of the field, within which the discovery of foundations was first made. In a direction nearly parallel with the road just named, and not more than from 600 to 700 yards distant from it, is another road leading to Cambridge. In both instances, the remains are on the west side of these public highways; but there is a feature near the latter which merits remark, the Borough Ditch, adjoining the road, or, rather, intercepted by it, and extending westward. It is several hundred yards in length, and, thus far, regular and distinct in its breadth and depth; but tillage has effaced all further traces of its extent in either direction. The railroad passes over the ground midway between the ruins of the two ancient dwellings, the one of smaller dimensions being in a south-easterly direction from the larger mansion, with which another building is in close proximity: but its all these remains will be better understood by a particular reference to their forms and dimensions, and their relative positions, with regard to the modern appropriation of the ground, be more readily imagined by an examination of the different plans annexed, it will be unnecessary to dwell at greater length upon this part of the subject.

I see no reason to doubt the accuracy of the conjecture that two of the buildings recently discovered were residences of persons of consequence in the immediate neighbourhood of an important station. The extent and order of the plans upon which they were built, would lead to the supposition that they were mansions of no common character. Both houses had their principal fronts facing the east, and, in both instances, the wings advance before the centre, but more boldly in the larger of the two. As the description I am about to give will, perhaps, be more clear by the examination of each separately, I will limit my attention to the one standing nearest to the village of Ickleton, about a quarter of a mile southward of the Church—the remains of which were brought to light early in August of the last year. It measures about 100 feet in length; the extent of the wings is 68 feet, and their width 25 feet, projecting 15 feet from the centre or body of the house. Attached to the south-west angle by a wall of inconsiderable length, in a slant direction, was a building the foundation of which measures 53 feet by 24 feet, unequally divided into three parts by other foundation walls, the largest nearly 1912 feet in width in the centre. The west side of the house must have presented a very irregular appearance in elevation. The hypocaust is in the centre, 16 feet square on the inside, partly within the walls of the house, and jutting out considerably beyond their boundary, but falling short of the wings, which are narrower on this side than in front. The western- most extremity of the south wing, 12 feet square within, contained another hypocaust; but, at the time of the destruction of the building, these underground portions suffered so excessively, that only a fragment here and there escaped removal, so that the regular order in which the brick piers were originally placed cannot now be ascertained. This smaller hypocaust appears to have been constructed for the communication of heat to the apartments at the south-west angle, the flue being carried through the oblique wall whereby they are connected with the main building. All the ground-floors of the house were on one level, 16 to 18 inches below the soil, and 12 inches below the present summit of the walls. The floor of the hypocausts is little more than 2 feet lower than the floor of the house, nearly the full depth to which the foundations of all the walls are carried. In no instance is any additional substance given to the walls, for the sake of a broader basement; the tallest fragment does not exceed 3 feet 6 inches in height, and it is of equal thickness throughout. It should be observed that nearly the whole of the work now seen was intended to remain buried in the ground, and that, if the walls above were reduced, the diminution took place on a higher level. The ground, to a considerable extent, slopes away from the village before named, both towards the east and south; the descent is gradual and regular, and it has been proved that the whole area occupied by the building was excavated to one level depth, in order to receive the foundations; and such was its solidity, that nothing, in addition to the thickness of the walls, as already observed, was deemed necessary for their permanent security, beyond the precaution of filling up the cavities with the solid material which had been previously removed. The fact that the plan as we now view it, refers only to the foundations, presents a difficulty with which it is impossible to contend successfully; there is no accounting for the purpose intended by the introduction of several of the walls—they are all bound together in so complicated a manner that no distinction can possibly be made between those designed merely as ties for security, and others provided to support the principal weight of the superstructure.

This baffles conjecture as to the order of the principal rooms; their position, facing the east, admits of no doubt, and it would not be difficult to arrange a plan to suit these remains, however unsafe it might be to attempt a description of what we may suppose the house to have been when perfect.

The floors of several of the lower range of apartments remain in a tolerably perfect condition, and, judging from the appearance of the ground during the recent excavation, accumulation has carried it above their level, whereas at the time of building, these basement floors were above the surrounding ground. The external walls are 2 feet 8 inches and 2 feet 6 inches in thickness, and not many of the cross walls are of less substance. They are uniformly composed of flint and chalk, well compacted and laid in courses, the external angles being formed of brick of the usual dimensions: this material occurs in layers in other places, but was not generally used underground except to give firmness to the angles, and in these positions the quantities were not sparingly applied, as may be seen by reference to the annexed figure. The floors of the rooms were mostly overlaid with composition of light colour, but two, opening to each other, one towards the south, 12 feet 10 inches by 11 feet in the wing, the other 26 feet 2 inches by 9 feet 2 inches on the west side, were finished in a superior manner, having had a kind of skirting formed of concrete and finished with cement, the floors being laid with the collected fragments of tessellated pavements and freestone, bound together with gravel and lime, and forming an even and solid floor, the strength of which has not been materially impaired by the damp which has proved so destructive to a portion of the materials of the walls. It should be observed that as soon as the foundations were constructed, the inside surface of the walls throughout were coated with plaster—a coarse composition of broken brick and lime, and then the hollows filled with rubbish to a level height, and covered with the floors composed in the manner described. The principal hypocaust has a double line of brick pillars remaining, five courses high, near the north wall, which is pierced with two flues in a vertical direction, 12 inches in width, but its perfect form is not seen. Attached to the west wall and extending in nearly parallel lines, are four distinct walls of flint, indicating that this part, at least, required a preparation of greater strength than that afforded by brick piers 7 inches square. These walls were added at the time of some alteration in the building over, as the plaster appears on the boundary wall in places where these flue walls have been destroyed—they are 2 feet 6 inches, 2 feet 4 inches, and 2 feet 3 inches in thickness, 10 inches apart; and attached to one, is a brick pier, the recommencement of the usual mode of construction beyond the point where the necessity for the stone-work ceased. The fire was kindled on one side, and the chamber for this purpose is also clearly defined in the smaller hypocaust at the south-west angle, on the floor of which, portions of several of the piers remain.

The plan of the other mansion, discovered at Chesterford, was of a more compact kind than the one just described. (See Plan). It exceeded 100 feet in length on either side, and each end measured 49 feet, the width of the wings being 26 feet, and the depth of the centre or body of the house full 40 feet. Each wing contained two apartments, and the centre three, towards the east, with a gallery or corridor at the back. The hypocaust was sunk under the room in the north-west angle, the flues being formed in a solid mass of flint-work, the cavities are about 9 inches wide, laid herring-bone fashion, the sides being finished with plaster. The adjoining room retains a fragment of the tessellated pavement with which it had been completed: it is in small squares of an uniform red colour. The principal walls are 2 feet 8 inches in thickness, composed in the manner common in this neighbourhood, of flint and blocks of chalk in even courses, but without any extra thickness at the bottom. The angles, as in the previous example, are formed wholly of brick, varying from 1512 inches to 1012 inches square, and 812 inches to 112 inch in thickness, and mortar joints of 1 inch. There is no appearance of this material in any other part of the construction. The whole of these foundations have sustained considerable injury: at the highest point they measure 2 feet 7 inches, but none of the walls have been entirely uprooted. The course of the flues designed to communicate warmth to all the apartments, seems to be clearly indicated by the thinner walls upon which they were supported, passing from the heating chamber in two places, from one along the gallery and turning at right angles stretching along the south wing, from the other by a branch extending along the centre, but at a greater distance from the front wall than in the parallel line of flue on the west side. The same mode of giving security to the foundations and of preventing in some degree the penetration of the damp, was adopted in this as in the foregoing instance: in both, the process of excavation has produced a vast variety of specimens of painting, showing that the walls of the different apartments of these houses possessed expensively finished decorations of this kind. The colours remain perfectly brilliant, and several fragments of plaster thus finished were found of sufficiently large dimensions to exhibit figures and patterns, such as a foot and the lower part of the toga, of (apparently) a person dancing, a very perfect red rose and flowers, arranged as trellis-work. A small circular pillar of stone, exactly similar to one found in the Roman villa at Hadstock, was discovered here: pottery also in abundance appeared, but in small fragments, many of superior quality, and with embossed ornaments, as well as much of a very common kind. Tiles of a curved form, some with zigzag patterns, flanged on one side, like those used to form covers to graves, or over apertures, were among the rubbish removed from the ruins, and the bones of animals have been discovered on all these occasions.

The subject of the latest discovery in this prolific tract of ground is of singular interest, on account of the general resemblance the building represented by the foundation bears to a "temple," the name which was at once given to it by the workmen upon the disclosure of its complete figure. Without adopting this notion, or hazarding too strong an opinion as to what might have been the precise use of the building in question, there can be little doubt that it was designed for some public purpose. It stood about 100 yards from the first mentioned villa, and had two walls extending from its eastern side, one in the centre, the other being an elongation of the north end of the structure. Nothing exists to show that this was anything more than an enclosed space of open ground; if it were, it is singular that all traces leading to a different conclusion should have disappeared, so much being left of what is proved to have been a building of regular figure, with exact internal arrangement. But we must accept the remains in the condition in which we find them. As mere foundations, they exhibit nothing more than the solid basement which upheld the edifice, every trace of which is gone, and nothing else was found buried in the earth within or around the walls applicable to any part of the superstructure. The dimensions within the walls, which are 3 feet in thickness, are 78 feet by 36 feet. It enclosed two ranges of pillars 712 feet distant from the blank walls, designed, it would seem, for the support of the floor, the room over having been undivided. This is probable from the slenderness of the pillars and their sustaining basements, which are little more than 3 feet square, of rough flint-work, having tie-walls connected with those of the exterior; and, in one instance, at the north end, the tie is carried from pillar to pillar across the centre. There are seven detached piers on either hand; upon three towards the east, and upon four on the opposite side, are still to be seen the blocks of stone upon which the pillars were deposited; these are nearly 2 feet square, each formed of a single block of Ketton stone. The design presents no particular merit, and the whole is rendered more irregular by the partial manner in which the plinth blocks are uniformly edged on two of the sides. The average height of these remains corresponds with that of those before described. The building, on being reduced to ruins, was left to lie encumbered and overspread with earth and rubbish, screening the remnants from further ravage, and they have remained undisturbed in the condition in which they were left to the present time."

We cannot close these memorials of the successful labours of Mr. Neville, which have contributed so largely to the extension of Archaeological science, and added to the treasures of his instructive Museum at Audley End, without the renewal of grateful acknowledgment for his generous assistance on the present occasion. Our cordial thanks are also due to his zealous and obliging coadjutor in these pursuits, Mr. John Lane Oldham, to whose friendly aid we have been frequently indebted in the endeavour to record the discoveries of which he had been a daily witness. A. W.

- ↑ A novel and interesting example of the occurrence of a Christian symbol amongst Roman remains in England, is afforded by the fragment of "Samian," ornamented with a Cross, and found at Cataractonium. See a representation of this relic, communicated by Sir William Lawson, Bart., in a subsequent page.

- ↑ The "Antiqua Explorata," and "Sepulchra Exposita," noticed in this Journal, vol. v. p. 235.

- ↑ In stating the conjectures regarding the ancient appropriation of this building, we must admit our inability to offer any satisfactory conclusion. Although neither Temple nor Basilica, it is very probable that it served some public purpose.

- ↑ Itinerarium Curiosum, 1776. Stukeley surveyed the remains at Chesterford in 1719.

- ↑ Reliquiæ Galeanæ, Bibl. Topogr. Brit. vol. iii. part 2, p. 113. In Plate IV., Fig. 4, an outline plan is given, corresponding in general form with the ground-plan developed by Mr. Neville's excavations.

- ↑ The Durobrivæ of Antoninus Identified and Illustrated, &c. London, 1828. Compare Plates XXVIII. and XXX.

- ↑ Antiquities of Norfolk, by the Rev. R. Hart, Plate II. Norwich, 1844.

- ↑ A similar usage, as regards cremation, existed amongst the Greeks. See the account of the mode of burying a Greek child, in Stackelberg, Gräber der Hellenen. The bones were arranged symmetrically, with Greek vases of various sizes.