Confiscation in Irish history/Chapter 1

CONFISCATION IN IRISH HISTORY

CHAPTER 1

THE TUDOR CONFISCATIONS

The History of Irish Confiscations may almost be said to be the history of Ireland from the first coming of the Anglo-Norman invaders until five centuries later, when confiscation ceased, apparently for much the same reason as a fire burns itself out, because there was nothing more left to confiscate.

The first confiscation, following on the invasion, differed radically from those that came later, because it was carried out by right of sword, without any attempt at justification by legal quibbles. To some extent the Normans in Ireland were only following the example set by their grandfathers in England.

But there was one important point of procedure which has profoundly differentiated the history of the two countries.

William the Conqueror claimed to be lawful King of England, whose right was disputed by the Pretender Harold and other rebels. If the English lost their lands it was as rebels. Theoretically he confirmed all previous laws and customs, and left all loyal subjects in enjoyment of their own.[1]

Practically, at first a considerable number of Englishmen kept their lands, and though this number was afterwards greatly reduced, there was no legal barrier to the acquisition of land by an Englishman, and no Englishman could be deprived of any lands he had, unless under some alleged ground for dispossessing him.

The result was that in a hundred years the two races began to amalgamate, and that at the death of King John, if not sooner, the amalgamation was complete.

But the procedure in Ireland was quite different.

The Irish, with but very few exceptions, were dispossessed of their lands in the conquered districts. Even Giraldus Cambrensis comments on this as likely to hinder the process of conquest. And Sir John Davies in his "Discovery of the True Causes why Ireland was never Entirely Subdued" devotes several pages to showing how the native Irish were shut out from the enjoyment of English laws, and were reputed as aliens.[2] And in particular he dwells on the fact that the native Irish were deprived of their lands.[3] He says—"And though they (the Anglo-Normans) had not gained the possession of one-third of the whole kingdom, yet in little they were owners and lords of all, so as nothing was left to be granted to the natives." And in his letter to the Earl of Salisbury dealing with the Plantation of Cavan he declares—"When the English Pale was first planted all the natives were clearly expelled, so as not one Irish family had so much as an acre of freehold in all the five counties of the Pale." Sir J. Davies is an authority not always to be blindly followed. We can, however, check his statements from the lists of forfeiting proprietors in 1641. From these we find that in Louth, Meath, Dublin, Kildare, South Wexford, Waterford, there were practically no landowners of Irish descent.

In the beginning, no doubt, the process of confiscation—expropriation as some modern writers prefer to call it—was not complete. Mac Gillamocholmog was left in possession of much of south County Dublin. The country round Ferns was left to Murtough Mac Murrough.

The Irish proprietors were not expelled from portions of Westmeath, Ossory, and Leix.[4] But their tenure was precarious. They were allowed to retain the more inaccessible and barren districts until such time as the settlers might feel able and willing to occupy them. Dr. Bonn declares that the law held all the Irish, except "the five bloods," to be villeins, and so incapable of holding freehold estates.

The position, in fact, of those whose lands were not occupied by the settlers was singularly like that of the natives in Rhodesia at the present day. As long as it suited the ruling class they might occupy certain districts, paying whatever rent or Other dues might be extracted from them. But at any moment colonists might settle on these lands, driving them off altogether, or allowing them to remain in a more or less servile condition.

Modern writers seem to hold that the Irish ought to have been, or actually were, satisfied with this state of affairs, just as eels are said to like being skinned.[5] The lower orders, we are told, benefited immensely by the more settled government, with its ensuing security, brought in by the settlers. But this view takes no account of the loss of property and position suffered by the free clansmen. No doubt the servile classes did rise in position, or, what was much the same, saw those who had been their superiors depressed to their own level.[6] But to the free clansmen, and above all to the leading families, the new state of affairs must have been intolerable.

A native Irish writer sums up the position tersely. The foreigners considered every foreigner noble even if he was ignorant of letters, and considered none of the Gael to be noble, even if he owned land. The most exhaustive account of the new order consequent on the Anglo-Norman Invasion is to be found in Dr. Bonn's Englische Kolonisation in Irland, a work indispensable to all students of Irish history.[7] He sums up the position of the Irish shortly—"der Ire war Sache, nicht mehr." "The Irishman was a chattel, nothing more."

Of course the natural result of this was to prevent any coalescence of the two nations. The Irish had to submit to loss of land and of personal liberty, or to fight. Naturally they chose the latter course, helped as they were by the difficult nature of the country, the small numbers of the settlers, and very soon by the feuds of the newcomers. The weakness of the central government soon became apparent. The settlers by themselves were not strong enough to effect a thorough conquest. The Irish learned military skill from the invaders, courage they had never lacked. The result was that some hundred years after the first invasion the Irish began to hold their own; half a century later they began to win back from the colonists the lands which they had lost.

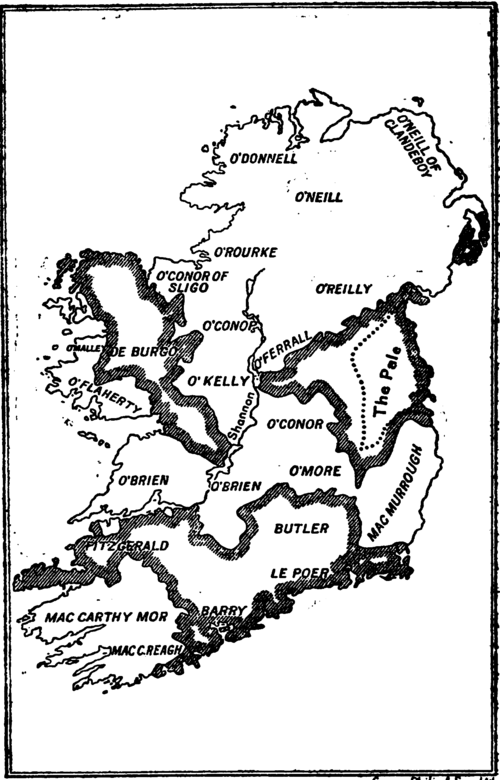

Nor could the Kings of England win over the natives and blend both peoples into one nation by granting to the Irish the protection of the English laws, or by giving them a legal title to the lands still in their occupation. The former course was made impossible by the opposition of the colonists; and the Crown, having granted away practically the whole island to the settlers, was debarred from the latter. The result was that at the opening of the reign of Henry VIII., close on three and a half centuries after the first invasion, the island was divided very unequally between the two nations. About one-third was held by the descendants of the colonists,

George Philip & Son. Ltd.

|

MAP II. |

Of course during this long period a certain amount of assimilation of the two races had taken place. Inter-marriages had become fairly frequent. A very large number of the settlers had adopted Irish laws and manners, and ruled their lands after the fashion of the Celtic chiefs. Nearly all of them had learned the Irish tongue, having in many cases completely abandoned the French or English of their forefathers.

Here and there, too, we find Irish landholders in the districts occupied by the settlers. There were such under the Butlers in south and mid Tipperary, under the Desmonds in Limerick, under the Barrys in Cork.[8] But the number of these was few, and it is noteworthy that the "degenerate" Anglo-Norman Burkes of Mayo and Galway had left scarcely any native landowners in the districts subject to them.[9]

And as regards the mass of the Irish, those of them in the districts subject to English rule had obtained some at least of the rights of citizens. At any rate they could no longer be murdered with comparative impunity.[10]

But viewing the island as a whole, we may distinguish between districts in which all the landowners were of Anglo-Norman descent, and others which were entirely in the hands of the native Irish. In the former districts we must distinguish between those parts, such as the four counties of the Pale, the south of Wexford, Waterford, Kilkenny, &c., where English laws of inheritance prevailed, and those others such as Mayo and Galway in which the settlers had completely adopted Irish customs, and where the inheritance of land was in accordance with the Irish customs of tanistry and gavelkind.

As regards the districts in Irish hands the chief point to be noted is that the Irish element was quite free from any foreign admixture. Some countries such as Tirconnell and Tirowen had never been occupied by the invaders; in others, such for example as Sligo and north Tipperary, the settlers had been altogether rooted out.

Common to the whole island was an almost complete divorce between occupancy of the land and the legal ownership of it. The whole of Ireland had been parcelled out among the invaders, and the claims of their descendants still held good in law. No length of occupation could give a valid title to an Irishman to any lands ever held by an Englishman. Even where there had never been effective occupation it would seem doubtful, whether any Irishman could claim a legal estate.

And in the districts in the hands of the colonists there was a great confusion as to title. The Burkes of Connaught held their lands in defiance of the law, and disposed of them according to tanistry as regards the chiefs, and to gavelkind as regards the lesser proprietors. The title of the Desmonds to their vast possessions was more than questionable. Irregular marriages, illegal alienations had thrown doubt on the titles of many of the minor lords.[11]

All over the island reigned confusion, which could only be put an end to by the intervention of the Government.

When Henry VIII. determined to do in Ireland what he had successfully done in Wales—namely, to unite settler and native in one commonwealth, the following was the state of landed property in the island. Two-thirds of the country was in the hands of the old Irish, who, in the eyes of the law, had no title to the lands they held. The other third was in the occupation of descendants of the settlers. West of the Shannon the De Burgos and all their following held their lands in defiance of the Crown. They had completely abandoned English law, and dealt with their lands after the Irish laws of tanistry and gavelkind. East of the Shannon the lesser proprietors of English descent as a whole held their lands by titles valid in English law; but the titles of the great lords, as I have said above, would too often not have stood an investigation conducted on the lines of the English laws of inheritance.

Henry at once grasped the necessity of a settlement of the land question. As heir to the vast Mortimer inheritance he was already owner of Ulster, Connaught, Leix, and other lands. Here he could give legal titles to the actual occupiers, whether Irish or Anglo-Irish. But over the rest of the island any policy of settlement and reconciliation was hampered by claims of the settlers to lands actually held by the Irish.

The rebellion and forfeiture of the house of Kildare, and the famous statute of Absentees, greatly simplified this difficulty as regards Leinster and Munster, and left Henry free to deal directly with the Irish clans.[12] It has often been said that what he did amounted in reality to a concealed system of confiscation. The lands belonging to the clan were to be handed over to the chief, and in case of his rebellion would then be seized and divided among English settlers. I have dealt with this theory elsewhere.[13] It is sufficient to say here that, though in certain cases this was the actual result of Henry's settlement, there seems no evidence that he intended to vest in the chiefs the lands of their clansmen. As a matter of fact the lands of the O'Tooles of Powerscourt were divided among the clansmen, and again in negotiations with the O'Conors of Offaly—negotiations which unluckily were never brought to completion—the intention was to provide for all claimants to land under Irish custom.

We clearly see, both from the Composition of Connaught in 1585, and from the Books of Survey and Distribution, that the effect of Henry's grants to O'Brien of Thomond and Mac William Burke of Clanricard, was to give them a title good in English law to the lordship of their countries, with the various rights and profits attaching to it, and to the landlordship of the actual castles and demesne lands set apart by the clan for the defence of the territory and the support of the chief. There was of course some injustice here, for of these castles and lands the chief was only a trustee, so that at his death they went or should go to his successor by tanistry: whereas by the new arrangement they were to go on his death to his heir according to English law. But this was an injustice more theoretical than real, and can only have affected the immediate kinsmen of the chief.

The confiscation of the possessions of the House of Kildare and its adherents, and that operated by the Statute of Absentees are the only instances from the reign of Henry VIII. But no "plantation" or introduction of any new strain into the population followed on them, and the effect if not the intention of the latter seems to have been to improve the position of the native Irish occupants of the lands claimed by the forfeiting absentees.

But Henry's grants[14] contained in them the germ of future troubles. In the first place, for some reason unknown to us, they were few in number; and secondly they were so vaguely worded that unscrupulous chiefs, or unscrupulous officers of the Crown, were able at a later period to maintain that the grants actually did give to the chief the landlordship of the clan lands.

With the reign of Mary we come to the first actual case of confiscation accompanied by the dispossession of the occupants of the land, since the days of the invasion.[15]

The territories of Leix and Offaly lay near to the borders of the Pale, touching for a considerable stretch the lands lately subject to the Earl of Kildare. Leix, the south-eastern portion of the modern Queen's County, had been occupied, in part at least, in the early days of the conquest. In the division of the great Marshall inheritance it had come to the Mortimers. But as Friar Clyn tells us, Lysaght O'More "had forcibly expelled the English from his lands and patrimony, for in one night he burned eight castles of the Englishmen, and destroyed the noble castle of Dunamaise belonging to Lord Roger de Mortimer, and usurped to himself the dominion of his fatherland. From a servant he became a lord, from a subject, a prince." Lysaght died in 1342. The Mortimer claims passed ultimately to the Crown. But, in spite of vicissitudes of fortune, for two centuries Lysaght's descendants ruled from the rock of Dunamaise.

Irish Offaly, as it is sometimes called to distinguish it from that part of the ancient territory now included in Kildare, was held by the 0' Conors and their subject clans the O'Dempseys and the O'Dunnes. The latter held the barony of Tinnahinch, in Queen's County, the O'Dempseys held Portnahinch in Queen's County and Upper Philipstown, in King's County; the lands directly under O'Conor comprised the remainder of the eastern part of the modern King's County.[16]

The O' Conors had been close allies of Silken Thomas in his rebellion. Vigorous campaigns and family quarrels greatly reduced their power, and during the later days of Henry VIII. we find alternate hostilities and negotiations going on between them and the Government.[17] At one time it seemed likely that the chief would be made a baron, and that his brothers and all other possessors of lands should obtain legal titles for themelves, and their heirs.[18] Unluckily for the O'Conors this was never brought about. Renewed hostilities under Edward VI. led to the complete overrunning of their lands, and the exile of both O'Conor and O'More, who finally surrendered to the authorities and were sent to England, where O'More died.[19]

This was the first considerable success obtained by the English over the old Irish for more than two centuries, and accordingly the project was formed under Edward VI., and materialised under Mary to extend the shire ground, and secure it by a settlement of men of English blood.

As to the title of the Crown to the lands, Offaly had been claimed with more or less of legal right by the Earls of Kildare, and by their attainder their rights were vested in the Crown. Leix as part of the Mortimer inheritance already was Crown property. The fact that the O'Conors had never been dispossessed of their lands and that the O'Mores had recovered theirs two centuries before was not allowed by the authorities to have any weight, since as alien enemies the Irish had no rights valid according to English law.

The area of confiscation by legal subtleties had, however, not begun, and Parliament contented itself with vesting in the King and Queen the countries of Leix, Slewmarge, Offalie, Leix, and Glynmalire, merely asserting that these lands were their Majesties', and making no attempt to prove any title.[20]

Another Act gave power to the Deputy, the Earl of Sussex, to dispose of the lands to all and every of their Majesties' subjects, English or Irish "borne within this realme, or within the realme of England."[21]

It is to be noted that for the first time since the J invasion power was given to make provision for the Irish. Leix was to be divided, according to a subsequent project, between the original inhabitants and settlers whether from the Pale or from England, and such of the natives as were considered fit to receive grants were to be made freeholders.[22]

Already, three years before Mary's accession, there had been a plan for a settlement put forward by some of the gentry of the Pale. Some settlers had already penetrated into these districts, but this had only led to a new outbreak of the Irish, who were not subdued until 1556.

It is to be noted that the land of the O'Dunnes—Iregan—is not mentioned in the Act of Confiscation. This territory, in fact, was left in the hands of the Irish until the reign of James I. And although Clanmahere, the land of the O'Dempseys, was included in the confiscated area, no effectual confiscation ever took place. O'Dempsey, following the usual fatal policy of the petty Irish chiefs, broke away from his lord, O'Conor, and made terms for himself. In 1563 the then O'Dempsey received a grant which made him owner in fee of all the lands of his clan.[23]

The rest of Offaly, and Leix and Slewmargie[24] were divided among English and Irish grantees.

But the Irish did not tamely submit to any encroachment on their lands.[25] Insurrection followed insurrection—eighteen separate risings are counted between Sussex's first plantation and the death of Elizabeth. Again and again the O'Mores expelled the colonists, broke down the forts, and raided far and wide into the adjoining lands. But the power of the state, helped as it was by jealous neighbours, proved too strong in the end. After half a century of warfare, carried on with the most barbarous cruelty, the remnant of the free clans of Leix, less than three hundred persons all told, were transplanted into Kerry, where Patrick Crosby, the descendant, if we are to believe Irish accounts, of O'More's harper, who had risen on the ruins of his former masters, undertook to give them lands on an estate which he had acquired near Tarbert. Of the O'Conors, most of the chief perished in these wars, a few retained some portions of their former territory.

The new settlers, though reputed English, were often, it must be remembered "mere" English of the Pale. Many, if not most of them, were Catholics. As such their sons or grandsons took part in the wars of 1641—51 on the side of the Confederate Irish, and were duly, as Irish Papists, deprived of their estates by Cromwell.

The reign of Elizabeth is marked by two confiscations on a great scale. The first, that which followed on the death of Shane O'Neill, was only a confiscation on paper, but, on account of its importance in following years it deserves careful study.

Henry VIII. had paid some regard to Irish usages in his dealings with the chiefs. Murrogh O'Brien, last King and iirst Earl of Thomond, was to be succeeded in the Earldom and the lordship of the country not by his son, but by his Tanist, Donough, son of Murrogh's elder brother and predecessor, Conor. Murrogh's son was to be contented with a lesser title, that of Baron of Inchiquin. In a similar fashion Con O'Neill was allowed to select a successor to his dignities, to be named in the patent of the Earldom. For some reason unknown to us he passed over his legitimate sons, and chose as his successor a certain Ferdoragh, anglice Matthew, who was certainly illegitimate, even if he were really Con's son at all. At Con's death the clan rejected Matthew, and chose Shane as O'Neill. He held his ground and compelled Elizabeth to recognize him virtually as lord of almost all Ulster.

But after his tragic downfall and death an Act was passed in 1569 for his attainder.[26] This Act is something of a literary curiosity.

It must be remembered that according to the strict letter of the law Ulster already belonged to the Crown, in right of the Mortimer inheritance, and no title to land therein could be valid in law unless derived from the Crown, the Mortimers, or their predecessors in the Earldom. Now, in the early days of the conquest great parts of Down and Antrim and some of Derry had been overrun and settled. In the fourteenth century, however, a branch of the O'Neills—O'Neill of Clandeboy—had expelled most of the settlers, and seized the greater part of the district east of the Bann and Lough Neagh. Some remnants of the settlers remained in the peninsulas of Lecale and the Ards in Down; and in Antrim the lands along the coast at one time held by the Missetts or Bissetts were claimed by a branch of the Scotch MacDonalds in virtue of the marriage of one of their chiefs to a Bissett heiress. As the MacDonalds were alien enemies it is doubtful if this claim was good in law.[27]

But in the rest of Ulster matters were different. Here, whatever grants may have been made by De Courcy or the De Burgos, no permanent settlements had ever been made, and the native Irish had never been dispossessed. Furthermore, by accepting rent or tribute from some at least of them their position as landowners had to some extent been recognised. And Henry VIII. had received all the chiefs as subjects, and hence, implicitly at least, recognised their rights to the territories they held, although in only one case, that of Con O'Neill, had he secured those rights by an actual grant.

The Act of Attainder gets over all these difficulties with considerable ingenuity. It traces the Queen's title to Ireland and Ulster from King Gormund, second son of the noble King Belin of Great Britain (both needless to say entirely unknown to history) then gets to surer ground with the "conquest" of Henry II., then comes to the grant to De Courcy, and the subsequent devolution of the earldom of Ulster through the Mortimers to the Crown. Incidentally it makes the quite untrue statement that the Act of Absentees vested in the Crown the earldoms of Ulster and Leinster.

Then, having to the satisfaction of the faithful commons proved that Ulster belonged to the Crown, it with curious want of logic proceeds to enact that Tyrone, Clandeboye, O'Cahan's country, the Route, the Glynnes, Iveagh, Orior, the Fews, Mac Mahon's, Mac Kenna's and Mac Cann's countries shall all be vested in the Crown, thus tacitly excluding Tirconnell and Fermanagh.[28] The truth seems to be that Elizabethan lawyers had not yet arrived at that total disregard for the equitable rights of the Irish that marked those of the Stuart period. They seem to have felt the injustice of attempting to deprive the Irish on a mere legal quibble of those lands which they had held without question since the days of Henry II. Hence the enacting part confined itself to confiscating the lands of those Irish who had actually been in rebellion under Shane.

Furthermore, since many of the lesser chiefs of Ulster had manifestly followed Shane only on compulsion, the Queen is prayed to deal leniently with the survivors, and to grant to them such portions of their said several countries to live on by English tenure "as to your Majesty may seem good and convenient." Finally, the Act saves the right of all "meere English" who had rights before the 20th of Henry VIII.

This Act seems to have altogether ignored the rights of Hugh O'Neill, Baron of Dungannon, son of Matthew, to whatever had been granted to Con. Furthermore, it avoided the difficult question as to what lands had belonged to Shane and other chiefs, and what had belonged to the clansmen, by confiscating everything except the church lands in the countries named. At a later date we shall see what advantage was taken by James the First's lawyers of the sweeping provisions of this Act.

The government soon made it known that it did not intend to take any steps to interfere with the lands of the Irish who had submitted. Turlough Lynagh O'Neill, who had been chosen by the clan as Shane's successor, was received into favour, together with all the other chiefs who, more or less on compulsion, had followed Shane.

In spite of this pacific policy advantage was taken of the Act to try some experiments in actual J confiscation and colonisation in Ulster. Grants of portions of the lands east of the Bann and Lough Neagh were made first to a certain Smith, then to Walter Devereux, Earl of Essex. But these attempts at confiscation, after much labours, and atrocities almost past belief, ended in the death or ruin of the grantees, and so need not be dwelt on here.[29] But though Ulster was left for a time undisturbed, in Munster a vast scheme of confiscation and settlement took shape. It is not clear whether the first steps were due to private enterprise, or to the initiative of the government.

A knight of Devonshire, a certain Sir Peter Carew, put forward claims to estates in Carlow and Meath, and to the moiety of the "Kingdom of Cork" as granted by Henry II. to Robert Fitzstephen. His claim to the barony of Idrone in Carlow,[30] and to an estate in Meath actually held by a certain Chevers was upheld by the courts.

It is the fashion to ridicule his claim to lands in Munster. To recognize it was contrary to the principles which had guided Henry VIII. in his dealings with Irish land, and the Tudors in general followed Henry's policy in this respect. But it was certainly the kind of claim that the Crown lawyers in the later days of James I. would have taken up with avidity. With the more accurate knowledge of the history of the early settlers which has been made possible in recent years we can no longer blindly accept the statements made by former writers that the Carew claims had already been investigated and set aside.

We need not accept the mythical "Marquess Carew" who, before such a title was known in England, held part of the coast line of Cork, and "gave his name" to the castle of Dunamark.[31]

But there had been Carews with great possessions in south-west Munster, although several generations had passed since any of them had had any effective occupation of the districts in question. At the moment the Earl of Desmond, who held a large part of the Fitzstephen and De Cogan inheritance, and claimed to be rightful owner of most of those parts of Cork and Kerry actually held by the Mac Carthys and their subject clans, had, to escape a worse fate, surrendered all his estates to the Queen. It was not yet certain whether she intended to pardon him and restore the lands; and to Carew and certain friends and neighbours of his the opportunity seemed a favourable one to obtain riches for themselves, and to establish the English power securely in all the sea coast from Cork to the mouth of the Shannon.[32]

Accordingly propositions for a confiscation and settlement on a great scale were put forward, whether suggested in the first place by the government, or by the gentlemen adventurers is not clear. The immediate effect was a rebellion, sometimes known as the first Desmond rebellion, sometimes as the Butlers' wars, in which the Mac Carthys and the Butlers for once united with their hereditary enemies the Geraldines.

Under the leadership of Sir James Fitz Maurice Fitzgerald, a near kinsman of the Earl of Desmond, the rebellion lasted for some three years, and deluged Munster in blood. The Butlers and Mac Carthys soon fell away from the combination, and made their peace with the Crown, leaving Fitz Maurice to carry on an unequal struggle alone. The whole story is told vividly, though inaccurately, by Froude. The rebellion so far achieved its object that all plans for a confiscation and plantation were dropped; and so the subject need not detain us.

Sir Peter Carew died in 1575, and we hear no more of his claims in Cork and Kerry.[33] The lands which he had recovered in Idrone passed to his nephew, and then by purchase to the Bagenals, a family of English settlers. The head of this family was executed as an Irish Papist guilty of murder in 1641, by the Cromwellian government, after the submission of the Irish forces in Leinster, another curious instance of how the Protestant planter of one generation turns into the Irish Papist of the next.

At the Restoration it was held that he had been unjustly put to death and the lands were restored to his children.

The second confiscation on a large scale during the reign of Elizabeth followed on the suppression of the great Desmond rebellion in 1583.

The procedure adopted on this occasion is worthy of close attention, especially as it is misrepresented in most of our histories. We constantly read statements to the effect that the vast estates of the Earl of Desmond and his adherents, covering half of three counties, and amounting to half a million acres, were confiscated and divided among English "planters." As a matter of fact the three counties of Cork, Kerry, and Limerick have an area of over 3,600,000 acres, and of this extent at the outside 400,000 English acres were finally confiscated.[34]

The whole question of the actual extent of the Desmond estates, their claims and their title to the lands which they either held or claimed is an intricate one, and would be a subject worthy of investigation. Here we may say that through royal grant, or as heirs of the De Cogan moiety of the "Kingdom of Cork" or by purchase or marriage the Earls held central Kerry, the Baronies of Kerrycurrihy, Imokilly, Kinnatalloon, and other large territories in Cork, most of Limerick west of the Maigue, and large tracts east of that river, the western baronies of Waterford, and several manors in Tipperary. In addition they put forward claims more or less well founded to supremacy over the native Irish clans who under the two great branches of the MacCarthy house, MacCarthy Mór, and MacCarthy Reagh, held all west Cork and south Kerry, as well as to the lordship over some of the "degenerate" Anglo-Norman families in these counties and in Limerick.

If we go back to the flourishing days of the Anglo-Norman colony in the reigns of Edward I. and Edward II. we find these possessions divided up into manors. In each manor the chief lord had a castle, the head of the manor, and a certain extent of land in demesne, worked by servile or semi-servile labour, while other portions were held by free tenants, either by Knight's service, or for fixed rents with various defined obligations towards the lord.[35]

In the sixteenth century this state of things persisted in outline, although much overgrown and disguised by Irish usages, and by innovations which had grown out of the lawless state of the country. On the demesne lands of the lord lived a mass of cultivators, mostly of Irish origin, all tenants at will, or at best holding by Irish custom, which would not be recognised by English law. Many of these were still for all practical purposes serfs, and looked on as such both by Irish and English; for villeinage lasted in Ireland long after it had disappeared in England, and was finally only abolished by Chichester in 1604—5. Others were in a better position, the descendants of the Betagii of the earlier inquisitions. These, though unfree according to English ideas, may have ranked among the native Irish as of free status, and economically may have been in a fairly good position, with rights of inheritance, and security against eviction, based on Irish law. Others again may have been to all intents and purposes personally free, belonging to recognized Irish free clans, but not having any permanent landed estates.

But in addition to the inhabitants of the demesne lands there were all those who could claim a freehold estate. Some were offshoots of the Geraldine house, others were descendants of those persons to whom the original tenants in capite had in turn granted large tracts to hold by Knight's service. These had manors of their own, with demesnes and dependent freeholders; they were bound to follow the Earl in war, and to render him other fixed feudal duties and payments. Then there was a very large number of smaller freeholders, mostly of English descent, all bound to pay fixed rents, and render certain services to the Earl. There were some Irish clans in this position.[36]

Then there were the dependent lords, such as the Fitzmaurices, Barons of Kerry or Lixnaw, and the Barretts of Co. Cork, who did not actually hold their lands from the Earl, but who, by more or less of compulsion, had been forced to pay him tribute, and follow him in war.[37] In this class, too, were some minor Irish clans, such as O'Conor Kerry, who had never been dislodged from their lands, but who acknowledged the suzerainty of the Earl.

Finally, there were the two great MacCarthy chiefs, with their multitude of subject clans, MacCarthy Reagh of Carbery, and MacCarthy Mór of Desmond. The former, it was claimed, was bound to follow the Earl in war, and to pay him yearly one hundred beeves.[38] Part of the lands of the latter—the baronies of Iveragh and Magunihy in Kerry—had actually been in possession of the Earl's ancestors in the thirteenth century. The MacCarthys had long since expelled the settlers from these districts, but the Earl still claimed superiority overMacCarthyM6r,a claim which the latter strenuously disputed, as well as a yearly payment of £214 11s. 2d.[39] Concerning this we know that portion of it was assessed on specified townlands in Bere and Bantry, but we may well have some doubts as to the regularity with which it was paid.

Now, the question at once arose—what of all this great inheritance had actually fallen to the Crown by the attainder of the Earl and his adherents?

Acts were passed (28th Elizabeth, Chaps. 7 & 8) attainting the Earl and a large number of his adherents by name. The second Act further attainted all who had died and been slain in their actual rebellion, or had been executed by martial law. But all who had survived the rebellion and who were not mentioned in these Acts had at one time or another been pardoned, and so, to use Sir J. Davies' phrase, "stood upright in law." Those attainted by name had almost all perished during the rebellion, and of the survivors some of the principals were afterwards pardoned.[40]

At first the idea of the Government was to take the widest possible view of the extent of the forfeitures. It was estimated that 577,000 acres had fallen to the Crown. Even the great estates of Fitzgerald of Decies, who had rendered considerable services during the rebellion, were claimed on the ground of a flaw in the grant to his ancestor from one of the Earl's predecessors.

An extensive plan of colonisation was formed. Its details are so well known that we need not go into them. It is sufficient to say that over fiftygreat proprietors—all English and Protestant—were to be created, each of whom was within a given time to settle a specified number of English families, some as freeholders, some by lesser tenures, on his properties. Irish tenants, if allowed at all, were to be moved from the wilder and more inaccessible lands, and to be settled in the open country, where they would be less able to give trouble.

At once a chorus of protest arose from those freeholders of English descent, who saw themselves affected by the new project. It was claimed on behalf of the Crown that as these lands had yielded to the Earl all sorts of Irish exactions—cuddies, cosherings and refections, bonnaught, horses' meat, and dogs' meat, and all the long lists of "cuttings and spendings" which we find so often quoted in the State Papers, the occupants were merely tenants at will. But against this the occupants protested. The Cogans, Cantons, Supels alias Capels, Poers and Carews in Imokilly showed ancient charters proving their title to their lands before Desmond or any Geraldine had any footing in those parts.[41] All uncertain charges which they had yielded to the Earl had but been extorted by force, and they had always protested against them.

Even in the case of those exactions which at first sight seemed to English officials most arbitrary, there were certain fixed limits outside of which the Earl did not go.[42]

Long disputes raged round these points. Various commissions were sent to Munster to determine the matter. The report of the first was distinctly adverse to the old inhabitants. But these did not submit and the controversy went on until the year 1592, nine years after the Earl's death. It was decided finally in favour of the old inhabitants. All who could make reasonable proof of being freeholders were secured in their property, paying to the Crown or to the Undertakers whatever fixed rents and services they had paid to the Earl, and compounding at a certain sum for all the uncertain payments which did not clearly rest on mere extortion.[43]

The result was that, instead of the estimated 577,000 acres, only 202,000 were confiscated and given to the Undertakers.[44] So far, therefore, was the project of a great English colonisation defeated. Besides, those "Undertakers" who finally secured lands did not fulfil the conditions laid down for them; far fewer English families were brought over than had been arranged for, and Irish tenants were brought in to fill the gaps. Of some thirty "Undertakers" only thirteen actually inhabited their properties in 1592,[45] and they had only "planted" two hundred and forty-five English families on their lands.

Yet, especially in County Limerick, a fairly considerable English element was introduced, much less, however, than our popular histories would lead one to believe. In 1611[46] the total armed force of the colonists only amounted to 196 horse and 537 foot. A curious feature, too, is that in 1641 a large number of the descendants of the "Undertakers" were Catholics. As such the Brownes of Killarney, the Spensers in County Cork, the Fittons of Any, the Walshes of Owney, the Thorntons and the Rawleys (these last said to be kinsmen of Sir Walter Raleigh) were all deprived of their estates by the Cromwellian confiscation."[47]

Among the traitors attainted by the Act 28th Eliz., Chap. 7, were several chiefs of Irish clans. The MacCarthys, as hereditary enemies of the house of Desmond, had supported the Crown against the Earl. But the fact that MacCarthy Mor stood by the Crown was enough to throw some of the Irish clans who were nominally subject to him on the side of the Earl. So we find among the list of those attainted, MacCarthy lord of Sliocht Owen Mor of Coshmaing, O'Donoghue Mór of Ross, some minor MacCarthy chiefs in Bere and Bantry, and O'Mahony of Kinelmeaky in Cork.[48]

The attainder of these chiefs opens a new era in the history of confiscation in Ireland. None of them had had any titles from the Crown valid in English law. Yet it was assumed that they held the whole territory of their clan in demesne—an assumption quite untenable not only according to Irish law, but according to the admission of English lawyers in other cases.[49] Hence it was held that by the attainder of these chiefs all the lands of their clansmen had fallen to the Crown; and these lands were accordingly allotted to the Undertakers.

But here a totally unexpected difficulty presented itself. MacCarthy Mór claimed that the lands of Coshmaing, Eoghanacht O'Donoghue, Clan Donnell Roe, and Clan Dermond were his; and that the sub chiefs and all the inhabitants were only his tenants at will, and that therefore on the attainder of these chiefs the lands should naturally pass back to him. And a similar claim was put in by MacCarthy of Carbery to the lands of Kinelmeaky. These claims were utterly preposterous from the Irish point of view. Both O'Donoghue in Kerry, and O'Mahony in Cork had been in possession of their lands for centuries before the MacCarthys had had any footing in these counties. They were both free clans acknowledging the MacCarthys as Kings of Desmond, following them in war, and paying them certain fixed rents in money or kind. Even this much of subordination was denied in the case of O'Mahony.

But the great Irish chiefs had skilled lawyers at their command; they knew that their claims might be made to appear plausible in an English court; they had rendered very great services to the Crown; above all, since a verdict for them would undoubtedly have been to the immediate advantage of the clansmen in the lands concerned, they might hope for a favourable verdict if the case was submitted to a Cork or Kerry jury.[50]

And so we find that a Kerry jury duly found MacCarthy Mór's title to most if not all of the lands he claimed.[51] Coshmaing, Eóghanacht, and Clan Donnell Roe had, however, actually been set out to Valentine Browne and his son Nicholas who were in possession.[52] They were hard to move, and MacCarthy was an improvident drunkard without any legitimate male children. Accordingly a compromise was arrived at. In consideration of a sum of less than £600 the lands in question were mortgaged to the Brownes, and the latter got a Crown grant securing the lands to them on the death of the Earl without heirs.

How the omission in the grant of the word "male" before the word "heirs" appeared at first sight to defeat the hopes of the Brownes, and how an almost endless contest dragged on on account of this between the Brownes and Florence MacCarthy, husband of MacCarthy Mór's daughter Ellen, and his son has been told at length in the "Life and Letters of Florence MacCarthy Mór." It is enough here to say that in the teeth of numerous decisions against them the Brownes kept these lands, which up to lately formed the immense estates of their descendant the Earl of Kenmare.[53]

On the other hand MacCarthy Reagh of Carbery failed to make out his case with regard to Kinelmeaky, and that territory, estimated at two and a half seignories, i.e., 30,000 acres, was set out to the Undertakers.[54]

The above are the first cases where the lands of an Irish sept or clan were confiscated on the pretext that they were the property of the chief. But / this pretext was as a rule not adopted in the reign of Elizabeth. The policy, followed all through her reign, was to confiscate the property of all who actually perished while in rebellion, and to pardon the survivors. Now, apart from questions of right or wrong, it generally suited the Crown better to recognise the clansmen as landowners. By following this policy a great amount of isolated confiscation took place all over the island, although nowhere except in Munster was there any confiscation on a sweeping scale.[55] And it is to be noted that, modern writers notwithstanding, there was a very considerable degree of leniency shown by the Crown even in the case of landowners who actually died in rebellion. Their lands were often granted to their sons or other immediate relatives.

To quote only one instance. When Donnell O'Sullivan Bere fled to Spain after his great march from Dunboy to Leitrim, his territory was not confiscated. The lordship of Bere, with the castles, lands, and rights attached to it, was handed over to Donnell's uncle, Sir Owen of Bantry, or rather to Sir Owen's son, another Owen. And we happen to have a list of the freeholders of Bere and Bantry made before the rebellion from which the remarkable fact appears that practically none of these were dispossessed, since in 1641 their representatives still appear as in possession.[56] This is entirely at variance with popular notions. For instance, Mr. T. D. Sullivan in his "Bantry, Berehaven, and The O'Sullivan Sept" says: "The kinsmen of Prince Donal did not all quit the country after his overthrow: they were not all killed; what happened was that they were robbed, despoiled, disinherited." A glance at the list of landholders in Bere and Bantry in 1641 as given in the Down Survey—one of the maps of which he actually published—would have shown him the absurdity of this statement.[57]

Among isolated confiscations worthy of note are that of Idrone, which I have already spoken of, Shilelagh which I shall mention later on and the Mac Mahon territory of West Corcabaskin in Clare. The ground for this last was the death of the chief while in rebellion—he was accidentally killed by his son. His territory was handed over to Daniel O'Brien founder of the renowned line of the Viscounts Clare.

Furthermore Walter, Earl of Essex, obtained in 1575 a grant of the territory of Farney in Monaghan, an ancient Crown manor which for over a century and a half had been occupied by a branch of the Mac Mahons of Oriel, who held it, nominally at least, tenants of the Crown. Technically, therefore, there was no confiscation here.

To sum up; at Elizabeth's death the area of actual confiscation and colonisation extended to about half Queen's County, one-third of King's County, large and scattered territories in four of the six counties of Munster, and scattered estates in Connaught, Leinster, Tipperary, and Clare. On paper there had been a great confiscation of Ulster, but in reality this had only so far permanently affected the barony of Farney in Monaghan.

The accession of the Stuart dynasty ushers in a very different period.

- ↑ In particular the men of London and of Kent seem to have had all their former customs guaranteed to them.

- ↑ Sir J. Davies expressly contrasts the policy of William the Conqueror in England with that of his successors in Ireland.

- ↑ Discovery. Here Davies exaggerates. There were more than "ten persons of the English nation" among whom all Ireland was cantonised.

- ↑ Orpen: Ireland under the Normans, Vol. II., p. 133.

- ↑ See Orpen and Knox.

- ↑ Pretty full records of the condition of the Irish tenants or rather serfs in the districts subject to the Anglo-Normans are now available in print: for instance in the "Pipe Roll of Cloyne," published in Jour. Cork Hist, and Arch. Soc., 1914; Begley's Limerick, and elsewhere.

- ↑ Specially to be studied in this connection are his chapters III., IV., and V. in Vol. I. For a summary see pp. 128—9, Vol. I.

- ↑ This appears from the Books of Survey and Distribution, and other Cromwellian Records. In Tipperary O'Neills and O'Fogartys; in Limerick, MacInnarighs or MacEnerys and O'Hurleys may be cited.

- ↑ See Knox: History of Mayo.

- ↑ Bonn, Vol. I., pp. 138—9. At first the murder of an Irishman entailed as only penalty the payment of damages to the English lord of such an Irishman, if he had one.

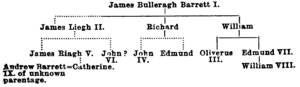

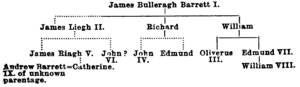

- ↑ See the extraordinary accounts of the marriages or want of marriages, and the ensuing family murders, in the case of the Barretts, of Co. Cork, as given in the Calendars of State Papers. The following rough sketch of a pedigree is curious:—

The numerals give order of succession of chiefs; dotted lines denote alleged illegitimacy.

These statements were made in the course of a dispute as to the lands, and are not to be implicitly believed. But they must have had some foundation in fact. - ↑ 1537. It vested in the Crown the lands claimed by the Duke of Norfolk, the Lord Berkeley, the heirs general of the Earl of Ormonde and others.

- ↑ "The Policy of Surrender and Regrant," Jour. R. Soc. of Antiquaries, Vol. XLIII., 1913.

- ↑ Henry made grants to O'Brien of Thomond, MacWilliam of Clanricard, O'Neill of Tyrone, O'Shaughnessy, Mac- McNamara, MacGillapatrick, and the O'Tooles of Powerscourt and of Castlekevin. Earl Hugh O'Neill claimed that the grant to Con O'Neill made him landlord of all Tir Owen (see Cal. St. Papers, 1606, p. 210). O'Shaughnessy in Cromwell's time appears as owner of the whole clan territory.

- ↑ Of course when, in the fourteenth century the Irish recovered lands from the settlers they slew or expelled the foreign occupants. This was the case notably in north Tipperary, in Leix, and in most of Carlow also. This of course from the settlers' point of view was "confiscation."

- ↑ The rest of King's County was held by O'Molloy, MacCoghlan, O' Carroll, and the Shinnagh or Fox.

- ↑ See the accounts of the capture of O'Conor's new and splendid castle of Dangean. The Irish had just begun to build elaborate castles when the introduction of moveable artillery rendered them useless.

- ↑ State Papers, Henry VIII.', Vol. II., pt. 3, pp. 328 and 560.

- ↑ Bellingham in 1548 overran the territories and built forts.

- ↑ Third and Fourth Philip and Mary, Chaps. 1 and 2.

A very full account of the proceedings with regard to Leix and Offaly, by Mr. R. Dunlop, is to be found in the English Historical Review, 1891. - ↑ Third and Fourth Philip and Mary, chap. 1.

- ↑ Mary in 1554 had released O'Conor at the prayer of his daughter, who, we are told, was skilled in the English tongue, and who went over to England to plead in person for her father.

- ↑ Fiants, Eliz.

- ↑ This is the south-east part of Queen's County.

- ↑ The conditions imposed on the Irish grantees were indeed of such a nature that it would have been almost impossible for them to keep them faithfully.

- ↑ XI. Elizabeth, chap. 1.

- ↑ This branch of the MacDonalds ultimately became known as MacDonnells.

- ↑ Cavan was at this period included in Conn aught. The O'Donnells of Donegal had been on the side of the Crown against Shane; and the Maguires of Fermanagh had apparently broken away from him before his death. Both O'Donnell and the Earls of Kildare put forward claims to some or all of Fermanagh.

- ↑ See in this connection the tale of the murder of Sir Brian MacPhelim O'Neill, of Clandeboye, his wife, and his followers—"young men and maidens" and of the six hundred women and children of the MacDonnells slain in Rathlin Island as told by the Four Masters and by Froude in his Reign of Elizabeth. There was also a grant of part of Co. Armagh to a certain Chatterton, which proved equally ineffectual.

- ↑ This was actually in possession of the MacMurrough Kavanaghs. An agreement was come to with them after a certain amount of disturbance.

- ↑ The whole question of the Carew claims would be a useful subject for study.

- ↑ Froude gives a detailed, and perhaps too highly-coloured account of this colonisation scheme. It came to nothing, and it is doubtful if it was ever really accepted by the government. See a letter of Sir Peter, Car. Cal., 1573.

- ↑ Sir Peter seems to have maintained his claims to the end; but he would appear to have been ready to be satisfied with a head rent from the Anglo-Norman lords and Irish chiefs who were in actual possession of the lands he claimed.

In 1603 Thomas Wadding writes to Sir George Carew on Sir Peter's title in terms that suggest that he hoped Sir George would prosecute the claim. Car. Cal. - ↑ Dr. Bonn puts it that 577,000 acres wore held at first to have fallen to the Crown, and that of these finally only 200,000 acres were confiscated. He does not say whether these were Irish or English acres. If Irish the figure would be over 320,000 English acres. But in the loose calculations of those days we must always allow for under estimates.

- ↑ Details about many of these manors in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries will be found in Begley's Diocese of Limerick.

- ↑ O'Hurleys and MacEnerys in Limerick.

- ↑ The Barretts of Cork had bound themselves by indenture to pay the Earl 12 marks yearly. But this they said had been imposed on them by force. From Clanmaurice the Earl had a money rent called "rent of the acres," amounting to £160 a year as well as 120 cows. Cal. St. Paps., 1610, p. 433.

- ↑ These Earl's beeves were paid by the freeholders of Carbery long after the death of the last Earl, to various grantees. See Cox: Regnum Corcagiense.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps. 1581, p. 368.

- ↑ The White Knight, The Knight of Glyn, Patrick Condon, or their heirs were all ultimately restored to their lands.

- ↑ Cal. State Papers, 1689, p. 256.

- ↑ See for the case of the "chargeable lands" Cal. State Papers, 1589, p. 256. Ibid. May, 1592, p. 528, for very clear directions as to what should be done. Ibid. Oct., 1592, p. 3 for account of the proceedings of the Commissioners. Car. Cal., 1594, p. 102, gives instructions to the final set of Commissioners for granting lands to the Undertakers.

- ↑ Even where they did rest on extortion, but yet had been paid from of old, if they were certain rents they were to be paid to the Crown.

- ↑ These are Dr. Bonn's figures. I cannot find, however, where he gets his 202,000 acres; possibly by adding up the acreage of the actual grants. The acres were probably Irish

- ↑ Cal. State Papers, 1592.

- ↑ Cal. State Papers, 1611—14, p. 218.

- ↑ The four families last-named were in Co. Limerick.

- ↑ Three MacCarthys of Clan Donnell Roe, and one of Clan Dermond, both districts in Bere and Bantry, are mentioned.

- ↑ Cal. State Papers, 1591—92, p. 467. By the attainder of O'Rourke only his own lands came to the Crown, and the other great lords of Connaueht, O'Kelly and others are in like case. "Not one acre of land (in Leitrim) but is ownered properly by one or other, and each man knows what belongs to himself." {Ibid., p. 469).

- ↑ It was pretty certain that once MacCarthy Mór was in possession of the lands there would be no plantation of English settlers, and therefore no eviction of the clansmen. Unfortunately, however, MacCarthy's need of money made him come to terms with the Brownes, leaving them in temporary possession of the lands in dispute.

- ↑ It is not clear what happened as regards Clan Dermond. Part of this territory was in possession of the Earl of Cork in 1641, part in that of its own chiefs.

- ↑ On the death of MacCarthy Mór at the final settlement with the claimants to his estates it was decided that all claims of his to lands in Clan Donnell Roe, Bere, Clan Dermond, and other places were to be extinguished. {Car. Cal., 1599, p. 301).

- ↑ The statement in Burke's Peerage may be consulted as an example of inaccuracy.

- ↑ Full details of the confiscation of Kinelmeaky with the attempts of some of the O'Mahonys to recover possession, and with a somewhat one sided account of MacCarthy Reach's claims are to be found in the Journal of the Cork Archaeological Soc., 1908, p. 189.

As showing the looseness of Tudor calculations of area it may be mentioned that Kinelmeaky has 36,000 English acres. - ↑ The Cal. Pal. Rolls, Jas. I., p. 115, gives a list of about seventy O'Byrnes whose estates, all mentioned by name, and mostly very small, some being only of two or three acres, were forfeited during the insurrections of Baltinglass and Tyrone.

- ↑ For Bere and Bantry the Calendar of State Papers, 1586—8, give details of the controversy between Donnell, and his uncle Sir Owen, lord of these countries by Irish law. Morrin Calendar of Patent Rolls, Eliz., 1594, gives the division of the lordship between them. The grant to Sir Owen, Cal. Pat. Rolls, IX., Jas. I., and the Down Survey and Books of Survey and Distribution show the state of these districts under the Stuarts.

- ↑ So O'Rourke's lands after his execution at Tyburn were granted to his son.