Confiscation in Irish history/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

THE PLANTATION OF LEINSTER

To James I. and his advisers the new plantation in Ulster appeared a great success. They began to look around for further opportunities for confiscation and these were very soon found.

In the early days of his reign James had made no distinction between the old Irish and the old English. Grants were freely made to all the chief men of both races who took advantage of the Commission for the remedying of Defective Titles or of that for accepting surrenders and making regrants.[1]

But already in 1611 Sir John Davies, on the look out for means to increase the revenue of the Crown, had pointed out the weakness as regards a legal title to their lands of many of the old Irish in Limerick and North Tipperary, the O'Kennedys, O'Mulrians and others. They had expelled the old English families planted in their districts; the heirs of these were not known; hence the lands had come to the Crown by common escheat. Davies, however, did not advise confiscation and plantation. He merely suggested that the Irish might be called on to compound for their estates, which would then be surveyed and regranted to them, no doubt for a substantial payment.[2]

There was, in fact, in the centre of the island, an almost unbroken stretch of territory, along the eastern bank of the Shannon from Leitrim to close to the city of Limerick, occupied by various old Irish clans of no very great individual strength. A large part of this district had formed part of the old kingdom of Meath, and so had formed part of De Lacy's lordship; other portions had been parts of the Leinster sub-kingdoms of Offaly and Ossory; others again were in Munster.[3]

Common to all this tract was that it had been granted to, and to a certain extent occupied by the early invaders; that the Irish clans had expelled the settlers in the 14th century[4]; that the chiefs had submitted to Henry VIII. and had thus been, at least, implicitly, recognised as subjects; that most of the chiefs had made surrenders to the Crown under Elizabeth and James, and had obtained, as they thought, a valid title to their lands; and, finally, that these surrenders and regrants had only affected the demesne lands and private property of the chiefs, without in any way conveying to them the estates of the free clansmen.[5]

The clansmen, moreover, had in most cases taken no steps to secure their rights against the Crown. Their rights as against the chiefs had been recognised, at least implicitly, and it had probably never occurred to them or to anyone else that the Crown would ever seek to deny them any title to what they held.[6]

Now they received a rude awakening. It was discovered that no length of occupation could give an Irishman any right to lands which had once been in English hands. None of the actual inhabitants, therefore, could have any rights to land unless they could show a grant from the former English owners, or—since the rights of these had largely fallen to the Crown—from the Crown.

The native inhabitants naturally enough protested against this theory. They pointed out that they had held their lands for at least two centuries, that they had been recognized as subjects and treated as landowners under Elizabeth and even under James himself, and that during the 16th century no Irish had been deprived of their lands on such grounds as were now put forward.

To this the answer was that the lands held by them had descended, in the case of the chieftaincies by Tanistry, and in the case of the clansmen by Gavelkind. In 1608 the Judges, after hearing arguments for and against, had decided that the law could not recognize descent by Tanistry, and two years before "it was resolved and determined by all the judges that the Irish custom of gavelkind was void and unreasonable in law. … And all the lands of these Irish countries were adjudged to descend according to the course of the common law."[7] The proviso was added that anyone who possessed and enjoyed any portion of land by the custom of gavelkind up to the commencement of the King's reign should not be disturbed in his possessions; but that afterwards all lands should be adjudged to descend according to the Common Law.[8]

Now the effect of these two decisions was practically to reduce all Irish claimants to land in virtue of the two customs condemned to the position of mere squatters.[9]

There remained the grants to the chiefs and to certain prominent members of the clans. Some of these could not be got over; but with others a means was found.

In some of the grants, based on a surrender by the chiefs, there was an express condition that the grant was to be void if a title for the Crown could be established by any other means.[10] And although the Act 12th of Elizabeth, empowering the Lord Deputy to accept the surrenders of the Irish chiefs and to regrant to them the lands thus surrendered, appears to have been framed so as to enable the Crown to give a valid grant to the de facto holders of the chieftainship, yet the decision of the judges in the "Case of Tanistry" was in effect that these surrenders and the consequent validity of the Elizabethan grants might be successfully challenged.[11]

Furthermore, there was frequently a pretext for challenging the legitimacy of the chiefs.

The Canon Law had multiplied impediments to marriage. The Irish chiefs had often taken advantage of this to obtain from the Papal authorities a dissolution of their marriages and liberty to contract new ones.[12] The government by sometimes upholding the validity of the Canonical impediments, and by sometimes refusing to recognize Papal dissolutions of marriage, could in many cases prove that the Elizabethan grantees had left no legitimate offspring.

Thus the lawyers found an ample scope for further proposed confiscations.

When the chief of Leitrim, Sir Teig O'Rourke, died in 1607 the legitimacy of his children was at once called in question, because it was alleged that their mother was really the wife of Sir Donnell O'Cahane.[13]

The first move in the new policy of confiscation under pretext of law was made not in the midlands, but in the northern portion of County Wexford. A large portion of this territory seems to have been left to the Irish at the first invasion.[14] In the fourteenth century the Irish of Leinster had elected as king a descendant of Donnell Kavanagh, illegitimate son of King Dermot MacMurrough,[15] and he and his posterity had expelled the settlers from most of Carlow, all north Wexford, and such parts of Wicklow as they had occupied.

On the death of Cahir "Mac Innycross," who had been chosen king in 1531 none of his kinsmen could be found willing to assume the dangerous royal title[16]; and through family feuds and the encroachments of the English the power of the MacMurrough Kavanaghs was greatly diminished, and the various subordinate clans seem to have largely fallen away from their control.

In particular the inhabitants of the northern portion of Wexford had begun to adopt English ways, and several of the old English from the southern part of the county had acquired lands among them either by purchase or by force.

In 1609 the inhabitants of this district determined to take advantage of the Commission for Defective Titles, and to surrender their lands in order to have them regranted to them by the Crown. Leave was granted to make the surrenders, and the freeholders obtained three commissions to the King's escheator and others to enquire into their lands and to accept their surrenders. On two of these nothing was done. But on January 27, 1610,[17] the surrenders were accepted. The time, however, limited by proclamation for surrender being then past, action was suspended because of the discovery in the

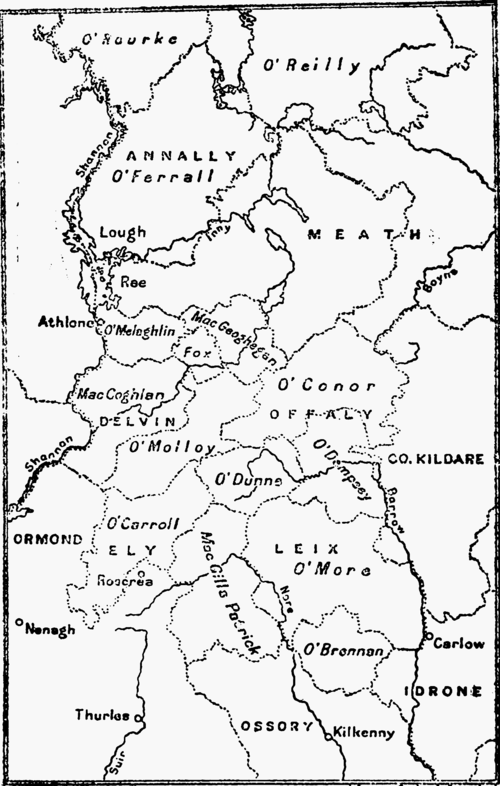

George Philip & Son. Ltd.

|

MAP III. |

The first reference in the State Papers to the King's title is in a letter from Chichester to Salis bury in June 1610, in which it is referred to as a "new discovery." In December of the same year he asked that the lands in question should not be granted to the natives or to any other suitor but to Sir Edward Fisher and Sir Laurence Esmonde according to a form sent by Fisher. It would appear that having now looked into the "new discovery" he had determined not to regrant to the natives, but to make a plantation, and that the grant thus asked for was merely of a temporary nature to enable him to proceed with the work.

The new title was briefly this. Art MacMurrough Kavanagh and his subject chiefs had agreed with Richard II. to give up their Leinster territories by a certain day, and to set out and conquer new homes for themselves in some other part of the island, of which the King was to give them estates of inheritance. Whether anyone ever believed that this preposterous agreement could be carried out seems open to doubt; besides it is not clear how Art and his chiefs could surrender lands of which they were only trustees for their clansmen.

However the King at once granted seven manors of the lands then held by Art and his subjects to Sir John Beaumont. His interest descended to Francis Lord Lovel who rebelled against Henry VII., disappeared at the battle of Stoke, and was duly attainted. His lands thus came to the Crown. Queen Elizabeth afterwards granted the manor of Dipps to the Earl of Ormond (really Dipps seems to have been Kildare property) and that of Shilelagh to Sir H. Harrington; the remaining five, lying between the Slaney on the south, the Blackwater of Arklow on the north, the sea on the east, and the Counties of Kildare and Carlow on the west were still in the King's hands, and the actual occupiers were only intruders.[19]

The next step was that in May, 1611, the King authorized Chichester to accept surrenders, and mentions a plantation. It would appear that the former surrenders were either unknown to him, or were considered to be of no effect. Accordingly Fisher, Esmonde and the King's Surveyor General visited Wexford, acquainted the natives with the King's intention to plant, proceeded to measure the country and persuaded fifty persons "of the best understanding and ability in the country and a few of the meaner rank" to make surrenders to the King without any manner of promise or assurance.

The report of Fisher and his colleagues is curious. They estimate the extent of the lands in question at 65,000 acres of profitable land, whereas the actual area of the Irish territories in Wexford is about 396,000 statute acres, or if we exclude the barony of Bantry, and that part of Scarawalsh west of the Slaney it is about 240,000 acres.[20]

They declare that two small territories totalling together 4,000 acres and called Roche's land and Synnott's land should not be interfered with, as the owners were old English, and claimed to have good titles, and in any case should not be disturbed. Two thousand acres belonged to the See of Ferns, and thirteen thousand had been recently granted to various persons by Letters Patent. There remained, then, 46,000 acres at the King's disposal. They considered that 24,000 acres were necessary to content the Irish and old English, but that few of the former should have lands, and, of those few, none of the Irish were to have more than 1,000 or less than 100 acres.

Thus 22,000 acres, or one-third of the country were available for a plantation. In reality the loss to the Irish was much greater than a third. For first there were several of the old English who had by purchase or by grant obtained heavy chief rents on certain of the districts in question, and these were now to be commuted for grants of land, and Sir Richard Masterson had claims to a large extent of land, which claims were to be fully satisfied; and secondly very few Irish were to be provided for in distributing the 24,000 acres set apart for the old inhabitants.[21]

These proposals caused dismay among the natives. Fortunately they were able to secure the services of many of the old English equally threatened by the project, and in particular those of a lawyer named Walsh.

It was held to be necessary that the King's title should be found by a jury of the county. At the first trial the jury refused to find a verdict for the Crown. Then the case was tried again in the Exchequer with the same jury. Eleven were for the King; five were against him, and were duly sent to prison. The case was then sent back to Wexford, and the eleven compliant jurymen together with Sir Thomas Colclough, and John Murchoe, a patentee in the new plantation, found a title for the King based on the forfeiture of the Beaumont grant.

While this trial was going on, or soon after, the inhabitants sent over to London (Dec. 1611) a petition by the hands of Walsh setting forth the injustice which they considered had been done to them. The facts set forth in it seem in the main correct, for they agree with the findings of a subsequent government commission of enquiry.[22] In particular they stated that when authority was given to receive their surrenders in February, 1609—10, Chichester himself had by Act of Council directed the Commissioners for Defective Titles to declare that they should have letters patent on their surrenders, the lands to be holden in free and common socage.

The Commissioners for Irish Causes after recital of the facts advised that the surrender of 1609 be accepted, and that regrants of all their lands should be made to the former holders, thus upsetting all plans for a plantation.[23]

Accordingly in January, 1612, the King wrote to Chichester, revoking his letter of May, 1611, and directing that there should be no plantation. Chichester protested to Salisbury against this decision and stayed all proceedings pending further directions.[24]

The King, influenced probably by Salisbury, changed his mind.[25] On the pretext that he had been deceived by the agents for the natives, he revoked his letter of January and informed Chichester that he might proceed with a plantation, but that owing to abuses on the part of those formerly concerned in the business Chichester himself was personally to see to the carrying out of it.

In December of the same year the King had received and considered Chichester's project, and transmitted for his consideration a scheme of his own.[26]

Noteworthy points in this scheme are that not many natives were to be made freeholders; that it was to be considered whether all or most of the natives should hold only for a term of years; and that lands now planted were not to be passed or sold to the natives. Furthermore it was suggested that 20,000 acres were not enough for the new settlers.

Chichester fell in readily with all the royal suggestions. The work of evicting the former owners and putting in the new ones was proceeded with.[27] But the scandal was so notorious that an investigation into the whole business was ordered to be made by the Commissioners sent over in 1613 to enquire into Irish grievances. The Report of the Commissioners gives a summary of the whole proceedings and some interesting statistics. They estimate the area at 66,800 acres, and say that the possessioners claim by descent after the custom of Irish gavelkind as freeholders, and as freeholders they have been empanelled on juries since the King's time.[28]

The number of freeholders who had made a surrender of their lands was 440, but the inhabitants declared that the true number was 667. Fourteen of them had patents from the Crown. Of the claimants only fifty-seven had got any lands, and no one had got any who failed to make out a title to 100 acres, or in some rare cases 60 acres. The vast majority of the former owners were thus deprived of their lands. The total population left in the condition of mere tenants at will is said to amount to 14,500. It is not very clear whether this number includes the dispossessed owners and their families. If it does, allowing five persons to a family, we find that the landowning class in Wexford numbered a little over 3000 persons, out of a total population of about 15,000.[29] This is interesting as being almost the only information we have as to the proportion among the Irish of the free landowning classes to the semi-servile dependent population who had no claims to land.

Furthermore the Commissioners found that the inhabitants complained of gross frauds in admeasurements.

The result of this Report was a new project, drawn up in London by the Lords of the Council, and transmitted to Ireland in August, 1614.[30]

This project completely upset all Chichester's proceedings. It first provided that all who claimed land, whether old English or Irish, and all patentees whether old or new, thus including such of the undertakers as had already got lands, were to surrender their holdings before Christmas, 1614.

Then a quarter of the lands in dispute, viz., 16,500 acres of arable and pasture lands besides barren mountain and boggy or unpasturable woods, were to be bestowed upon eleven of such new patentees as Chichester should choose: each getting 1,500 acres, "or such other fit natives as will accept the same if the said patentees refuse." The lands thus allotted to the undertakers were to be in the more inland and hilly parts, along the borders of the Irish countries of the Dufferin, Ferrenoneale, Shilelagh and the Lordship of Arklow; and those who actually held these 16,500 acres including " old pretended patentees" were to be competently satisfied by the rest of the inhabitants.

The remaining three-fourths of the country, comprising the parts along the sea and the more level inland parts, were to be repassed to such of the natives and former inhabitants as the Lord Deputy and his assistants shall deem fit to be freeholders; none of the freeholders to have less than twenty acres, and such as had formerly less to be made tenants to others either British or Irish. The portion set apart for the old inhabitants was however to provide lands to compensate Sir Richard Masterson and one of the Synnotts for chiefries arising out of some of the territories, and further to compensate Esmonde, Fisher and one Blundell for their labours over the plantation, besides providing an estate for "Brady the Queen's footman." Should the natives refuse to surrender, then the present patentees {i.e. the Undertakers and such of the old inhabitants as had obtained patents) were to be at liberty to stand on their patents, and the lands so refused to be surrendered were to be granted to others, of British birth, and then all parties were to be left to the law, but in the meantime the natives were to be continued in possession until evicted.

Chichester was much offended at the new project. We learn from Sir Oliver St. John in December, 1614, that Chichester was keeping entire control of the proceedings, although several persons had been named by the Council as his assistants.[31] And we also learn from the same source that " the inhabitants shun to surrender their estates."[32]

This was certainly bad policy on their part, especially as their agents, or some of them in England, had accepted the Council's project.

So in March, 1615, new directions came from London. Since the natives refused conformity with the King's project, Chichester was to proceed as directed in such an eventuality, i.e., to give the whole territory to Undertakers or old patentees; but all the natives were to be put back into possession of the lands already in the hands of the new patentees, until evicted by due course of law.

Chichester thereupon proceeded to distribute 23,300 acres among eighteen Undertakers, all Englishmen, and of course Protestants. To his nephew he gave 4000 acres, to his son-in-law 1000. To eight more Undertakers he was preparing to give 5,840 acres. But he forbore to carry out the full severity of the Council's order, as he thought that the London authorities would finally wish to give the old inhabitants some satisfaction, and so reserved 36,860 acres for them.[33]

He was right in his suppositions. The Council in England suddenly veered round again and, in December, 1615, sent Chichester letters of general restraint. They decided to adhere to the scheme of August, 1614, namely, to give three-quarters of the lands to the old proprietors and ordered that the new patentees should surrender their grants.[34]

Chichester of course protested against this in a letter to the Lord Carew, but he suggested that if his nephew Trevilian gave up his 4000 acres there would only remain 2,800 acres to be cut off from the Undertakers and that they "will undoubtedly be gotten in a measurement"—a significant admission.[35]

By March of 1616 Chichester understood that most of the new patentees had surrendered; but, as late as December of the same year we find him writing to the Lord Carew protesting against giving only 16,500 acres to the Undertakers, and suggesting that twenty of them should get 25,300 acres, leaving almost two-thirds to the old inhabitants.[36] In the same month he wrote to the Lords of the Council giving a history of all his dealings in the matter.[37]

His first plan had been to assign 32,000 acres to the planters, and 34,000 to natives: among these he must have included some at least of the native patentees. Then he explains the subsequent course of the proceedings, evidently trying to justify himself against any charges of unfair dealing. It appears that by now the old inhabitants, or the chief of them, had submitted to the King's decision of 1614.

In the meantime there must have been a curious state of affairs in Wexford. As far as can be made out, although it was finally decided that only one-quarter of the territory was to be given to the Undertakers, only the fifty-seven old proprietors provided for under the scheme of 1611, and possibly the old patentees, had so far got any of the lands thus reserved from the planters.[38]

The old inhabitants, possibly owing to the admixture of old English amongst them, showed great pertinacity in pushing their complaints. Chichester on his side was equally pertinacious. The resources of a superior civilisation were called into play; and by false measurements one-half of the whole country was set apart for the Undertakers, instead of one-fourth.

But the Irish prevailed so far as to have the lands resurveyed by the King's surveyor general. In March, 1618, the fraud was discovered and room was found to give freehold estates to eighty more of the old inhabitants. Three-quarters of the territory, less the area set apart to satisfy the claims of the Queen's footman, Esmonde, Masterson, &c. was exactly distributed to the natives, making choice of the chief of every sept and others found by the general office to have been proprietors, freeholders of less than 80 or 100 acres not being included in the distribution as not good for themselves.[39]

In this way while 150 of the chief inhabitants obtained estates good in law, all the smaller landowners were deprived of everything. They numbered certainly 290, possibly over 500. Two hundred of them proceeded to Dublin to urge their claims in person. They even pleaded for consideration on the ground that their ancestors had first brought the English over! For answer they were thrown into prison, and the Deputy St. John proposed to transport some of them to the new colony of Virginia: a short and cheap method of dealing with Irish landlords which might commend itself to modern Chancellors of the Exchequer.

Complaints still continued. In 1632 Hadsor, an English official who spoke the Irish language, reported that individuals had been unfairly treated and stated that the Irish gentlemen appointed to distribute them helped themselves to the lands which they were to divide amongst others.[40]

I have dealt thus at length with the plantation of Wexford because in it we find all the features of the confiscations carried through under James I. They took place in a time of peace, without any pretext of rebellion; they discriminated against the native Irish, who had, if anything, been rather better treated than the old English under the Tudors; they were founded on old titles for the Crown, based on legal quibbles and raked up out of the obscurity of centuries; they struck at the root of the Tudor policy which had in the main recognized the occupier as the equitable owner of lands: they upset or at least rendered insecure all grants by Elizabeth, or even by James in his early years, based on surrenders by the occupier. And at the same time they show a real desire on the part of the authorities in London to deal fairly with the Irish, a desire frustrated as a rule by the greed and unscrupulous methods of the officials on the spot.

Above all they exasperated the natives far more than any confiscation based on conquest in war could have done. Had the plantations been fairly carried out, it is possible that the Irish would not greatly have resented them. The land available was large, the population scanty[41]; if some lands were taken from the Irish, yet, as compensation, the rest was legally secured to them, the uncertain exactions of the chiefs were done away with, peace was secured. But the capital mistake was made of absolutely suppressing the small landowner, a mistake apparently honestly founded on the doctrine that "the multitude of small freeholders beggars a country." The result was that while the more influential clansmen were discontented, the smaller men, deprived of their all, lost all confidence in the justice of the administration, a loss that has never up to now been made good.

The plantation of Longford shows most of the features mentioned above. The territory of the O'Ferralls, the ancient Annaly, the modern County Longford, had been for nearly a generation the subject of controversy. First, under Elizabeth, the two chiefs O'Ferrall Boy and O'Ferrall Bane, seem to have endeavoured to "grab" the lands of the clansmen. These efforts had been successfully resisted; and the clansmen were recognised as the owners of the lands not comprised in the demesnes of the chiefs.

Next the Baron of Delvin and his mother had got a grant to be satisfied out of any forfeited lands in Longford which might have come to the Crown during Tyrone's rebellion; and during the early days of James I. a violent controversy was carried on as to what these grants amounted to[42] There were also charges of chief rents and of beeves, originally payable to the Crown, but which had been granted the one to Sir Nicholas Malby, and the other to Sir Richard Shaen.[43] Against these, or at least against the way in which they were assessed, the inhabitants protested.

It is noteworthy that in these controversies both the King and Chichester showed themselves favourable to the O'Ferralls, and that there was no hint of any attempt to deprive them of their lands.[44]

A portion of the O'Ferralls had joined in Tyrone's rebellion, and had been attainted and outlawed—chiefly, said they, through Lord Delvin's procurement. Lord Delvin sought to obtain possession of their lands, by virtue of a grant to him by Elizabeth of forfeited lands value £100 a year.[45]

The O'Ferralls had submitted to the Crown under promise of pardon and remission of forfeiture; nevertheless the widow and son of Lord Delvin had obtained a warrant to pass to themselves nearly one-half of the County Longford. The King, however, ordered Delvin's patent to be cancelled, and the O'Ferralls to be restored.[46] At first his idea was that the surviving O'Ferralls and the chief inhabitants should repossess what they had before the war, and that the lands of those who had died in rebellion should go to Lord Delvin.[47] But the latter got into trouble with the government,[48] and in 1608 Chichester proposed to get rid of his claims altogether, and to settle the O'Ferralls so that ' ' all the inferiors of their septs may hold immediately of the King.'[49]

Neither then, nor for some years afterwards, was there any mention of a plantation, but a settlement was delayed owing to the controversy with Shaen and Malby.

Apparently during this period it was discovered that a large part of the county was vested in the King, by virtue of the Act of Absentees, as having once belonged, at least in name, to the Earls of Shrewsbury.[50]

In May, 1611, the Lords of the Council gave explicit directions to grant all the lands in the county, after satisfying the claims of Shaen and Malby, to the ancient proprietors. Apparently even those whose feoffors or ancestors had been attainted or killed in rebellion were to be restored. A noteworthy point is the following direction: "Where small parcels are claimed by many through colour of gavelkind, the grant to be to the eldest and worthiest in each cartron, he being required to grant estates to others (if need be); yet they are to consider that the multitude of small freeholders beggars the country, whereof none to have less than one cartron."

Here there is a deliberate crushing out of the small landowners, who were to become leaseholders on the estates granted to the wealthier clansmen.

So far there had been no question of any confiscation or plantation. There is a gap in the records relating to Longford of four years, during which nothing seems to have been done towards securing the O'Ferralls in their lands. Then in 1615 came a letter from the King to Chichester, reversing all his former decisions. He finds "no remedy for the barbarous manners of the mere Irish which keeps out the knowledge of literature and of manual trades … so ready and feasible as, by first, by settling a firm estate in perpetuity on such of the present inhabitants as have the best disposition to civility … and, secondly, by intermixing among them some of the British. He is given to understand of some titles he has as well general as special to all or part of Longford, Leitrim and other Irish countries." Chichester was to inquire into these titles.[51] In other words, founding his right to Longford not on the surrender of the O'Ferralls but on the Statute of Absentees, he directed that the inhabitants were to be treated as intruders, and a plantation was to be made on the lines of that of Wexford.

It is noteworthy that, in this very same year, the King wrote ordering Letters Patent to be made out for their estates for all the landowners in Clare and Connaught, as had been intended by the late Queen at the time of Perrot's Composition of Connaught in 1585.[52] Three years later St. John prepared a scheme for a settlement. He estimated that there were 50,000 acres of arable and good pasture land in the county, besides lands of patentees and unprofitable land.[53] Incidentally we learn that many of the natives had built good stone houses and that they were "reasonably reclaimed by civil education." As a matter of fact in the Carew MSS. Vol. 625 we find an account of Longford which goes far to show that the distribution of land by gavelkind was not the uncertain and scrambling distribution which Davies in some of his pleadings represented it to be: but that what distribution there was was confined within the limits of the inheritance of one family. In Longford, as in Wexford, Fermanagh and Leitrim every acre had its owner, and each individual clansman knew what acreage he was entitled to. It is noteworthy that some of the estates were very small, and that they lay not altogether, but scattered in different townlands.[54]

Against this scheme of a plantation the O'Ferralls urged possession for centuries, the injustice of raking up an old forgotten title three hundred years old, the services to the Crown of some of them, their conformity to the laws, and above all the solemn promises of the late Queen and the present King, the Lord Deputy Devonshire, and the Lords of the Council.

But no attention was paid to their complaints, and a more or less voluntary submission was finally extracted from them. In theory three-quarters of the best part of the country was to be given over to the old inhabitants. But as usual, deductions were made from this to satisfy special favourites of the King or the Deputy, to redeem charges granted away by the Crown, to provide for forts and corporate towns. There were false admeasurements, the officials and the surveyors lived on the country during the survey and helped themselves to estates[55]; some of the old inhabitants by influence got more than their shares, others were deprived of what they were entitled to. The small landowners were swept away. Anyone who, after deduction of a fourth, saw his acreage reduced below 100 acres was liable to lose all: no one got less than 60 acres.

The dispossessed landowners were to obtain leases from the Undertakers, or from their more fortunate kinsmen. But none of the natives were to sell to any of the old Irish, or to give leases to them for more than forty years or three lives; provisions clearly against James' policy of making no distinction between the two races in his early days.

In the end 142 of the natives received estates. But amongst them we find about thirty names of old English extraction, men like the Earl of Westmeath who received the largest grant, the Earl of Kildare and several Nugents and Fitzgeralds.

Finally "it fell out so that divers of the poor natives or former freeholders of that county, after the loss of all their possessions or inheritance there, some ran mad, and others died instantly for very grief, as one James Mac William O'Farrell of Clangrad, and Donagh Mac Gerrot O'Farrell of Cuillagh, and others whose names for brevity I leave out, who on their death-beds were in such a taking that they by earnest persuasions caused some of their family and friends to bring them out of their said beds to have abroad the last sight of the hills and fields they lost in the same plantations, every one of them dying instantly after.[56]

At the same time as the plantation of Longford a similar project had been set on foot for the territory of Ely O'Carroll, and for Leitrim, and a general inquiry was made into the King's title to lands in Westmeath, King's County, and Queen's County.

Already in 1611 Chichester had informed the Privy Council that Ely appeared to be now of right part of His Majesty's inheritance. The grounds on which this title was based, as given in Vol. 625 of the Carew MSS. at Lambeth, are curious.

Sir Teig O'Carroll had held Ely by Irish custom, and without any title good by the laws of the realm, until mindful of his duty to his Sovereign he had made a surrender of all that he was in possession of to Edward VI. who thereupon made him a regrant of what he had surrendered.[57]

This was evidently, from the context, a surrender and regrant of the lands, castles and duties attached to the chieftainship, and not of the clan lands as a whole, although this is not explicitly stated in the abstract of title.

Sir Teig died without heirs male, and the lands reverted to the Crown. His base brother. Sir William, succeeded as O'Carroll. He too made a surrender, and obtained a regrant. [58]

He made a settlement of his property, and enfeoffed certain persons for this purpose. His lawful sons, named in the settlement, apparently predeceased him; for the MS. says that he left only one lawful child, a daughter named Johan, who was married to Redmund Burke.

When Sir William died his base son Sir Charles succeeded as O'Carroll. The feoffees of Sir Ham's settlement released to him all their rights; and so did his sister Johan, after her husband had died in rebellion.

Sir Charles died in 1600 leaving no lawful issue; but he had at least one son, a minor.[59]

Apparently then the lands, castles and duties attached to the lordship had reverted to the Crown. As to the rest of the inhabitants their claims were apparently set aside on the pretext that they held no estates known to the Common Law; although up to the time of the plantation they had been treated as freeholders in various dealings with the government.

Ely had 931 plough lands, each of 200 acres.[60]

Of these the Lord had had 37 in demesne, and a chief rent out of the rest of the country amounting to £70 lls. 7d. Under the plantation scheme young O'Carroll was to have ten plough lands; fifty other natives were to have forty plough lands divided between them; certain lands were set apart for forts, glebes, &c. Seven plough lands were already held by letters patent, and the residue—thirty plough lands—was to be divided among British servitors and undertakers.

The actual area taken from the clansmen here was not very great, since most of the lands set aside for the British settlers could have come from the demesne lands. But in practice the real hardship must have been that the smaller landowners lost everything.

As for Leitrim it had for some time attracted the attention of the government. In 1607 Sir Teig O'Rourke, Lord of Leitrim,[61] had died and the attention of the government had been called to a doubt as to the legitimacy of his children, for it was alleged that his wife had been previously married to Sir Donnell O'Cahane.[62]

Leitrim had been included in Perrott's settlement of Connaught in 1585. But it did not form part of the De Burgo Lordship of Connaught. It happened that at the time of the Anglo-Norman invasion Tiernan O'Rourke, King of Breffny, was also in possession of Meath, and by a curious reversal of the real state of affairs, the grant to De Lacy of Meath was held to include Breffny.[63] No permanent settlements had ever been effected in either Cavan or Leitrim. But in 1607 Richard Plunkett of Rathmore claimed Breffny O'Reilly in virtue of his descent from Margery, third daughter and co-heiress of Sir Thomas de Verdon, who on her father's death had received Breffny O'Reilly as her share of his lands.[64] And Lord Gormanston and a certain Mr. J. Rochford claimed Breffny O'Rourke, or most of it, in virtue of their descent from one Nangle to whom that territory had been granted by an early lord of Meath.[65]

Hence the O'Rourke title under the Composition of Connaught was not very secure. By the execution at Tyburn of Brian O'Rourke for having aided the ship-wrecked Spaniards of the Armada, the lands attached to the chieftainship had come to the Crown. But, as Bingham had pointed out to Burghley, his attainder had not affected the rights of the clansmen, for as to the rest of the country "every acre of land is properly ownered by one or other." But the clansmen themselvss were not secure. Many had been in rebellion; others had not fulfilled the conditions of the Composition.

In 1611 Chichester had noted that Leitrim was never well sub-divided, nor disposed to freeholders, but was left for the most part to the power and greatness of the chief of the O'Rourkes.[66]

So now, in 1615, designs were formed to remedy this by a resettlement of the country, involving a partial confiscation. The inhabitants seem to have made but little opposition. Young Brian, Sir Teig's son, and reputed heir, was the King's ward; but this was no protection to him. The Gormanston claims were found very useful in order to defeat the title of the O'Rourkes; but as against the King they were strongly resisted; and were finally bought off by a grant of lands contingent on the death of the late chief's widow.[67]

Some two hundred freeholders surrendered their lands. One-half of the country was divided among them; but here, as in other plantations, we must suppose that the smaller landowners lost everything.[68]

The work of confiscation went merrily on. That Mac Gillapatrick of Upper Ossory had received a grant of his lands from Henry VIII. with the title of baron; that his son had been " bedfellow" of Edward VI.; that the family since then had preserved among all temptations its loyalty to the Crown did not prevent the seizure of one-fourth of the territory, which was granted to the Duke of Buckingham.[69]

Sir John Mac Coghlan of Delvin had served the late Queen well in her wars; his estates seemed secure by a grant from her, and at the same time she had directed that the rest of the inhabitants of Delvin were to have letters patent, every man of his own; chief and clansmen in O'Molloy's country seemed equally secure; O'Dunne of Iregan had received from James himself a grant setting out fully all the rents and services which he was to receive from the clansmen in lieu of the old

George Philip & Son. Ltd.

|

MAP IV. |

Yet even here we find that curious inconsistency in wrong-doing which marks all James' dealings with the Irish. He or his advisers did not press the claims of the Crown to O'Melaghlin's territory of Clancolman, or to Mac Geoghegan's territory of Moycashel. Here much of the land was held by letters patent, and most of the rest, though formerly held by gavelkind, was now disposed of by conveyance, purchase, &c. according to the course of the Common Law. The King's title was doubtful, and the inhabitants were well disposed to civility; therefore it was recommended that there should be no plantation; but that the whole of the lands should be granted by letters patent to the inhabitants.[70]

The curious can find in Vol. 625 of the Carew MSS. at Lambeth summaries of the proceedings with regard to finding the King's titles in these districts, with most interesting details, the dues payable to the chiefs, the methods of estimating the areas, and other information which makes it very regrettable that, as far as I know, none of the contents of the volume have ever been calendared.[71]

There is one point in which the Leinster plantations differed very materially from that in Ulster. The mass of the Irish inhabitants were not expelled to make room for tenants of British extraction. It is true that the Undertakers were all Protestants, and almost exclusively British, and that they were bound to settle a certain number of British families on their lands. But they were allowed to have Irish tenants on the residue. To these, or at least to as many of them as had before been landowners, they should have given leases. But in most cases neither of these conditions was fulfilled. Very few British families were established—even the Undertakers themselves often were absentees—and the Irish seldom obtained leases, very largely it seems because they themselves preferred yearly tenancies.

Another point to be noticed is that the Irish landowners in these districts were forbidden to sell or give leases for more than forty years to any Irish—it is not clear whether old English were included in this prohibition.

The results of James' policy were that some years before his death the lands forming the present County Wicklow were almost the only Leinster districts in possession of the old Irish in which there had been no definite scheme of confiscation and plantation.[72]

It was of course considered "dangerous" that close to Dublin the fertile valleys and bleak moorlands of Wicklow should still remain to a great extent in Irish hands. Proposals were made to start a fresh plantation there. But the designs of Falkland, the Lord Deputy, found an unexpected check in this. The Commissioners for Irish Causes wrote to the Privy Council advising against any further plantations.[73] Those already undertaken had not yet been properly completed; they were causing general exasperation; they had been much practised by the private aims of many particular persons; every Irish landowner was beginning to feel that his turn might come next.[74] Falkland wrote protesting violently against these views. But James followed the advice of the Commissioners and for the moment a stop was put to confiscation.

Yet the Irish were not left unmolested. Falkland persisted in his designs on at least part of Wicklow. His dealings with Phelim O'Byrne, son of the famous Pheagh Mac Hugh, are some of the most discreditable transactions in the history of Irish officialdom. They are set forth at length in Carte's Ormond, and are dealt with both by Miss Hickson and Mr. Bagwell. As however they did not result in any sweeping confiscation and plantation they need not detain us here.[75]

Incidentally we may remark, as illustrating the confusion as to rights of property, that three distinct claims were set up, namely, that the district in dispute, the lands of Ranelagh and Cosha—the modern Glenmalure and the country around Aughrim and Tinahely—(a) belonged to Phelim Mac Pheagh O'Byrne, (b) belonged to the freeholders, i.e., the O'Byrne clansmen, (c) belonged to the King.[76]

However, projects for the plantation of that part of Wicklow known as Crioch Brannach or Byrnes' Country were put forward from time to time.[77] Lord Carlisle was one of the movers in the matter, and in 1631 obtained a grant of all the King's rights in the district. He had, however, to promise to settle the freeholders at a moderate rent and on just terms. But nothing seems to have come of this. In 1628 directions had been given that the freeholders were to surrender and have their lands back; and a letter from Lord Esmond to Lord Dorchester in 1631 says that by the former's means the Byrnes had passed their lands.[78]

In 1634 we have a draft from the King regarding a plantation. In this it is said that King James in 1611 had signified his pleasure that surrenders should be accepted and regrants made to the freeholders; but that the revenue secured had been too small. "We believed at the time" (possibly in 1628) "that the persons settled had good estates to surrender to us, whereas it now appears by report from the Irish Council that the property should belong to the Crown."[79]

Directions were given for a plantation. "Persons who hold by our former letters shall not be displaced when the Commission (to find the King's title) reports; but shall submit to our title and receive a portion of their lands, at the rent which you may think fit." The rest was to be divided among fitting persons, which probably means English Protestants. The Earl of Carlisle and others who had got letters patent were to be dealt with to surrender their lands.

It was probably in pursuance of this scheme that in April, 1638, an Inquisition was taken and a return made finding the King's title to Byrnes' country, that is, to the whole barony of Newcastle and parts of the baronies of Arklow and Ballinacor. It gives as boundaries the sea on the east, Killincargie and Delgnie and Glancapp on the north, Fartir, Sangheine, Imaal and Clonmore in Co. Carlow on the west, and on the south Shilelagh, Co. Wexford, and "the shires of Arklow."[80]

Thus both Ranelagh and Cosha were included in the area dealt with. The jurors found that Richard II. was seized of these territories, and so they had come to the King. This finding of course invalidated all previous grants, either to Englishmen based on the attainder and forfeiture of the freeholders, or to such of the freeholders themselves as had survived and had surrendered their lands and obtained regrants of them either under James or Charles. The lands thus declared to be in the King's hands were in or about 1640 vested in trustees who were to make grants to the Protestants of the lands of which they were possessed, no doubt on payment of certain fines.[81] The Irish freeholders were probably to be treated as in other plantations, i.e., they were to lose one-fourth or one-third of their lands, and receive good titles for the rest.

The outbreak of 1641 probably prevented any effectual steps for a plantation here. According to the Down Survey about forty-three Catholics had land in Byrnes' country in 1641. Summing up James' dealings with Irish land we find that in the six plantation counties of Ulster there had been an absolute confiscation, about one-seventh of the total area being restored to certain chief men of the Irish. In Leinster, the whole of Longford, the north-eastern portion of Wexford, the baronies of Brawny, Clonlonan and Moycashel in Westmeath, about two-thirds of King's County and one-third of Queen's County had been declared to be the property of the Crown. But here the rights of the inhabitants were to some extent recognized. In theory they were to retain three-quarters of their lands.[82] In reality, owing to sharp practices on the part of the officials, they did not retain anything like this amount, and furthermore all the smaller landowners were deliberately deprived of their property "as not good for themselves." Finally in Connaught County Leitrim had been treated in the same way as the Leinster counties.

In Ulster the plantation was accompanied by the wholesale eviction of the Irish from the greater part of the lands settled. They were only allowed to dwell in certain specified lands, viz., those granted to the Bishops, the servitors and the old Irish. In Leitrim and in Leinster there was no such removal of the old inhabitants.

As to the rest of the island the policy followed by James had been in the main an equitable one. To most of the Anglo-Irish lords and to many of the chief men of the old Irish he had given tenures good in law; and he had taken steps to secure in their lands the innumerable landholders in Connaught and in Clare.

- ↑ See Sir John Davies: Discovery.

- ↑ Car. Cal., 1611, p. 104.Some of the chiefs of these districts already had obtained grants from the King of the demesne lands and rents and services attached to the chieftainship. Davies probably referred to the smaller landowners.

- ↑ The clans were O'Rourkes and their subject clans in Leitrim; O'Ferralls in Longford; O'Melaghlins and MacGeoghegans in West Meath; O'Shinnaghs or Foxes, O'Molloys, MacCoghlans and O'Carrolls in the modern King's County; O'Dunnes and MacGillapatricks in Queen's County; O'Kennedys, O'Meaghers, Mac I Briens, O'Mulrians, O'Dwyers in Tipperary.

- ↑ Friar Clyn under date 1346 tells us that Thadeus son of Roderic, princeps of Elycarwyl, i.e., Ely O'Carroll, had slain, exiled and cast out from his lands of Ely those of the "nations" of Barry, Milleborne, Dc Bret and other English, And held and occupied their lands and castles.

- ↑ The grant for example to O'Molloy is explicit as to this. Carew MSS. Vol. 625.

- ↑ See the lists of chief rents, and the dues of cattle, hogs, oats, reapers, ploughdays, mowers, &c. in grants such as those to O'Dunne and to Mac I Brien of Ara in Cal. Pat. Rolls James I. and to O'Molloy. Carew MSS., Lambeth Vol. 625. Q. Elizabeth's grant to MacCoghlan granted to the chief all lands, &c. in his possession, and the "rest," i.e., evidently the clansmen, were to have letters patent. Car. MSS., Vol. 625.

- ↑ Quotation from the resolution of the Judges given in A. Ua Clerigh: History of Ireland to the coming of Henry II., p. 237.

- ↑ As a matter of fact the Books of Survey and Distribution clearly show cases in Connaught of lands divided according to gavelkind as late as 1641.

- ↑ Vol. 625 of the Lambeth MSS. founds the King's "general title" to these districts on the two facts that the chieftainships went by tanistry, but that there was no estate of inheritance thereby by the common laws of the Realm, but only a temporary taking of the profits thereof; and that those who held land by gavelkind have no estates therein by the common laws of the Realm.

- ↑ So in Elizabeth's grant to O'Molloy there was a clause that the grant was to be void if Her Majesty had any other right to the land either by record, Act of Parliament or otherwise, other than by O'Molloy's surrender. Car. MSS., Vol. 625.

- ↑ Le Case de Tanistry turned on the point as to whether a surrender by Conor of the Rock, Lord of the O'Callaghans by Tanistry, was valid in face of the fact that his predecessor in the lordship, who was the senior representative of the family, had under the Common Law made a settlement of his lands and lordship on his grandson and greatgrandson. This by Irish law he had of course no right to do. The Judges held that Conor had had no estate which he could surrender, hence the re-grant to him was void. I can find no instance in which this precedent was extended to other cases.

- ↑ For cases of doubtful marriages of the chiefs see those of the first Earl of Clanrickard, three of whose wives appeared before the Commissioners who were sent to decide who was heir to the Earldom; Sir Cormac MacTeig MacCarthy of Muskerry speaks of Ellen Barrett "whom he had used" as his wife. The marriages of the Barretts themselves werea source of litigation.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1607, p. 196, and 1611, p. 16.

- ↑ Orpen: Ireland under the Normans, Vol. I., p. 390. But Ferns appears later as an important manor of the lordship of Wexford. Then the Crown held the castle until the Mac Murroughs took it towards the end of the 14th century. They held it until 1536. Hore. Hist. of Wexford, Vol. VI.

- ↑ Donnell MacArt Kavanagh: chosen King about 1327: Journ. Kil Arch. Soc. Vol. II. New Series, p. 75.

- ↑ Hughes: Fall of the Clan Kavanagh: Jour. R. Hist, and Arch. Assoc, of Ireland 4th Ser. Vol. 2, p. 282. He gives the succession of the last kings of Leinster as follows:—Morogh Ballogh, died 1511; Art the Yellow, second cousin to Morogh'a grandfather, 1511—18; Gerald, brother of Art, 1518—1522; Morrogh son of Gerald, 1522—1531. It is uncertain whose son Cahir Mac Innycross was, or when he died. His successor Muriertagh, son of Art the Yellow, was only styled "MacMurrough." He died in 1547. A distant cousin, Cahir MacArt, succeeded, and in 1550 publicly renounced the style of "MacMurrough" which was never afterwards resumed.

- ↑ The report says 1609; this is probably old style, the year beginning on March 25th.

- ↑ The King's title was first spoken of during a trial between Sir R. Masterson and one of the Kavanaghs. This was before the orders for accepting surrenders were made. The Deputy had not heard of the King's title when the orders were made.

- ↑ This title is set out in the report of the Commission of 1613. Cal. St. Paps., p. 439.The seven manors were Fernegenall, O'Felmigh, Shelmalier, Lymalagoughe (or Kynelaghowe?), Shelelagh, Gory and Dipps. It is curious that we are not very certain as to why no such scheme was planned for parts of Carlow and Wicklow which had also been subject to Art MacMurrough.Of the manors mentioned above we know that Fernegenall and O'Felimy lay along the sea, north of Wexford harbour. (Orpen. Ireland under the Normans, Vol. I., p. 390). Gory is all or part of the modern Barony of Gorey, Shelelagh is obviously Shilelagh now in Co. Wicklow, which seems to nave been inhabited by O'Byrnes. There are two modern baronies of Shelmalier. Shelmalier east seems identical with Fernegenall: it is not clear how much if any of Shelmalier west was occupied by the Irish. The barony of Bantry was for the most part in Irish hands in the early days of Henry VIII.: some of it had since been seized by the Butlers and others, who had got grants of what they had conquered. It was not included in the area now in dispute. The "Duffry," between Enniscorthy and Mt. Leinster, also lay outside the area. The Statute of Absentees had vested Carlow and the feudal rights over English Wexford in the Crown.Other names mentioned are Farrenhamon, Farren Neale, Clanhanrick. Kilcooleneleyer, Kilhobuck. (Bagwell: Ireland under the Stuarts, Vol. I., p. 154).The boundaries were the Slaney, the sea, and the modern Co. Wicklow.See also Hore. History of Wexford.

- ↑ The Irish parts of Wexford west of the Slaney were apparently held to be vested in the Crown by the Act of Absentees, and had been dealt with by Elizabeth, at least as regards the chief men.

- ↑ The Report of the Commission of 1613 gives different figures. According to it nineteen Undertakers got 19,900 acres; Sir R. Masterson 10,000; fifty-six others of the old inhabitants got 25,000, leaving 12,000 acres available for "martial men," i.e. servitors.

- ↑ See the Report of the Commissioners sent over in 1613. Miss Hickson prints it in full.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1611, pp. 175—177.

- ↑ Chichester to Salisbury. March 5th, 1612. Cal. St. Paps., p. 252.

- ↑ King to Chichester. March 22nd, 1612. Cal. St. Paps., p. 259.

- ↑ December, 1612.

- ↑ May, 1613.

- ↑ This report is very inaccurately summarised in Cal. St. Paps. It is printed from Harris' Desiderata Curiosa Hibernica in Miss Hickson's Ireland in the Seventeenth Century. It says that 35,210 acres had been allotted to fifty-seven of the former inhabitants. Of this about 10,000 to Sir R. Masterson.Of the fifty-seven named, eight are said to be old patentees (one being a certain Richard Cromwell). Two other patentees are mentioned as having got no allowance under the scheme for the lands surrendered by them. The fifty-seven names include Sir Richard Masterson and about twenty-two "old English."

- ↑ If they are not included the total population would have been, roughly, about 18,000.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1614, pp. 492—96.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1614, p. 531.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 540.

- ↑ Car. Cal., February, 1616, p. 324.

- ↑ Apparently in the interval the old inhabitants, or some of them, had submitted.Car. Cal., 1616, Chichester to the Lords of the Council, p. 332.

- ↑ Car. Cal., 1616, p. 324.

- ↑ Car. Cal., 1616, p. 330.

- ↑ Car. Cal., 1616, p. 332.

- ↑ At least eight of the old patentees appear in the list of the fifty-seven old proprietors as printed by Miss Hickson.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1620, p. 303.

- ↑ Hadsor to the King. Cal. St. Paps., 1632, p. 681.

- ↑ Some of the Irish asserted that 100,000 people were affected by the plantation. This figure is quite impossible: the baronies in question had in 1901 about 45,000 inhabitants. The Commissioners apparently give the population as about 15,000. Even if it numbered 20,000 there was ample room for new settlers.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1605, p. 312, gives the case for Ld. Delvin. It would appear that it was chiefly O'Ferrall Bane and his followers who were affected.Cal. St. Paps., 1606, p. 536, and 1606, p. 45, also deal with this controversy.

- ↑ £200 a year to Malby; 120 beeves to Shaen. The latter is said to have been an Irishman of low origin. He claimed kinship with the O'Ferralls.

- ↑ King to Chichester. Cal. St. Paps., 1607, p. 134: also Deputy and Council to the Privy Council. Ibid, p. 157.

- ↑ Cal. Stat. Paps., 1607, p. 159. Statement of the proceedings in the case between Ld. D. and the O'Fs.

- ↑ By a letter of Jan., 1605—6: referred to but not given in Cal. St. Paps., 1608, p. 522.

- ↑ King to Chichester. Cal. St. Paps., 1607, p. 220: also same to same, 1608, p. 522.

- ↑ Amongst other things he was accused of having threatened to murder Salisbury.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., March, 1608, p. 437, Chichester to Salisbury, and May, 1608, p. 522, the King to Chichester on behalf of the O'Ferralls.

- ↑ In Feb., 1610, or possibly 1611, Cal. St. Paps., p. 581. Ld. Delvin states that it was by his travail and great charges that the King's title to Longford was first brought to light. In Oct., 1611, p. 148, we find the K's title through the Stat. of Absentees to the manor of Loughsewdie and other lands, making up a large part of the county, which anciently belonged to the Earls of Shrewsbury, mentioned as an obstacle to a final settlement.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1615, April, p. 35.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., July, 1615, p. 108.

- ↑ A survey given in Car. Cal., 1618, p. 381, states that there were 57,803 acres of arable and pasture and 8,387 of profitable wood in the county, besides 23,959 (profitable, unprofitable) either granted by patents, or abbey lands, 25,843 acres of bog, 12,459 acres of unprofitable wood and bog, 1,710 acres unprofitable mountain, and 195 acres glebe lands, in all 130,356 acres. The true area is 269,000 statute acres.

- ↑ The Inquisitions in the printed Volume of Inquisitions "Lagenia" show a minute subdivision of land especially in Wicklow. We read of one man having one-sixty-fourth part of each of certain lands, another having one-seventh of one-sixteenth, another having one-seventh of one-fourth of some lands, one-seventh of one-sixteenth of others and one seventh of one-sixth of others. These fractions are due to distribution by gavelkind. From the analogy of Wales it is possible to conclude that not the lands but the profits from them were really sub-divided, the lands being tilled or pastured in common.

- ↑ Such as Sir Christopher Nugent, H. Crofton, and Thomas Nugent of Collamber.

- ↑ Memorial from the inhabitants of Longford. Hickson: Ireland in the Seventeenth Century, p. 283, Vol. II.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., Oct. 1611, p. 148.

- ↑ 20th Eliz.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., July, 1613, p. 386, Viscount Butler, guardian of John O'Carroll, to have liberty to surrender and get a regrant of his estate.Cal. St. Paps., 1612, p. 278, asserts that it had been found by office that the country of Ely with divers seignories and castles had descended to John on the decease of Sir William and Sir Charles.It was asserted that John's mother was already married when she married Sir Charles.

- ↑ The real area of Ely is 102,900 statute acres.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps. 1603, p. 84. By the execution of Sir Brian O'Rourke Leitrim had come to the Crown. A grant is to be made to Teig O'R., only legitimate son of Sir B., and to the heirs of his body of whatever had lawfully belonged to his father.From Cal. St. Paps., 1591—2, p. 467, it appears that it was recognised that only the demesne lands had come to the Crown.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1607, p. 196, and Ibid, 1611, p. 16.

- ↑ Knox: History of Mayo, p. 314.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1609, p. 221. Breffny O'Reilly corresponded to Co. Cavan; Breffny O'Rourke to Leitrim: both together made up "the rough third of Connaught."

- ↑ Cal.. St. Paps., 1592, p. 590, and 1621, p. 334. The Earls of Kildare claimed the northern portion. Cal. St. Paps., 1591, p. 406.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1611, p. 10.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1621, p. 334. It cannot be maintained against the King because they have been expulsed by the Irish 200 years, and the land recovered from them at the charge of the Crown.

- ↑ The chief had had 166 quarters, and a yearly sum of £276 13s. 4d. out of 445 quarters held by the free tenants, in lieu of the former Irish exactions. Pat. Rolls, Jas. I., p. 9.

- ↑ The title was derived from Isabel Marshall who married Gilbert de Clare, through their son Richard, whose son, another Gilbert, had one son who died without offspring and three daughters and coheiresses, one of whom, Elizabeth, married William de Burgo. Then through the Mortimers it, with the rest of the de Burgo inheritance, came to the Crown. (Inquis. Lageniae).

- ↑ Lambeth MSS., Vol. 625.

- ↑ In Fox's country of Kilcoursey thirty natives besides some previous patentees were to have lands. There was no plantation. In Delvin sixty natives were to get estates, the same number in Fercal.In Iregan the chief was to have about three-eighths; thirty of the clansmen three-eighths, and the remaining one-quarter was to be given to British planters, to the Church, and to a corporate town. The area of Iregan is 53,000 stat. acres.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., May, 1623, p. 409, Ranelagh, Imale, Glencap, Cosha, part of Birnes', Shilelagh and Duffry not yet settled. Duffry was in Co. Wexford. Imale belonged to the O'Tooles. These also claimed Glencap, but the government held that it belonged to freeholders, dependent directly oa the Crown. Cosha was between Aughrim and Tinahely, in Wicklow.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1623, p. 427.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1624, p. 306, for the fears of the "holders of land within the English Pale."

- ↑ Much of Wicklow passed however at this time into English hands, partly as having been the property of freeholders who had died in rebellion in Elizabeth's reign, partly by the attainder of some of the chiefs in her time, partly as being of old the property of the Crown. The barony of Shilelagh seems to be an example of the latter case. Part of Phelim O'Byrne's lands were seized, and later on passed into the hands of Strafford.

- ↑ The whole controversy, first as between Phelim and the freeholders, secondly between both parties and the King, can be followed out in the Cal. of St. Paps. The lands claimed by Phelim, i.e., the territories of that branch of the O'Byrnes called the Gavel Rannell, must be carefully distinguished from the rest of the clan territory, the coast district from Delgany to near Arklow alluded to in the Calendars as "Byrnes' Country," in Irish Crioch Brannach. Points to be noted are: that Phelim undoubtedly tried to seize the clan lands, and asserted that he had four times obtained letters from James and twice from Charles to that effect; that he and his sons ultimately retained possession of part of the lands, although various planters, notably a Scotchman named Graeme got some: that the lands of "Byrnes' country" were held to be the property of the freeholders and that much of this district was granted to Parsons and others since many of the freeholders had perished in rebellion under Elizabeth; and that there are repeated instructions in the State Papers to pass the rest to the freeholders. Cal. Pat. Rolls. Jas. I. has on page 90 a grant of certain lands to Phelim, and of a rent of £100 old money of England out of the territory of Ranelagh and Pubble Kilcamman, which rent is payable by the free tenants and ter tenants in money or cattle.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1628, pp. 330, 380, 395; 1631, p. 604. Also in vol. 1647—60; Addenda, 1625—60, p. 338. The Cal. of Pat. Rolls Jas. I. has on p. 465 a surrender of lands in Byrnes' country by about 140 natives, besides some Palesmen and English. (17th James), ibid. p. 521 (19th James) there is a grant to Sir L. Esmond of lands both in Byrnes' country and in Cosha; but he is to regrant to the free tenants according to the proportions directed by the inquisition taken in the Co. Wicklow.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1631, p. 627.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1634, p. 52.

- ↑ Inquisitions Lageniae: Killinccargie and Delgnie are the modern Killincarrick and Delgany. Glancapp corresponded more or less to the parish of Kilmacanogue. Sangheine (Salvum Kevini) was the Church land round Glendalough, called St. Kevin's Land in the Down Survey. The "five shires" of Arklow apparently took in the parish of Kilbride north of the Avoca river, and as much of the present Barony of Arklow as lies south of that river. This district belonged to the Ormonds.

- ↑ Reference in Ld. Powerscourt's book on Powerscourt to a Patent of Charles II. reciting this. Also Cal. St. Paps., 1640, p. 238.

- ↑ And in a few districts there was no actual plantation or confiscation, i.e., in Clancolman, Moycashel and Kilcoursey, the King's title being doubtful.