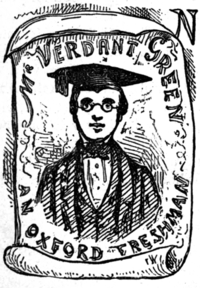

Little Mr Bouncer and His Friend Verdant Green/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II.

LITTLE MR. BOUNCER EXTRACTS FROM MR. VERDANT GREEN THE CAUSE OF HIS DESPONDENCY.

OW then! spit it out, Giglamps!" said little Mr. Bouncer, as he sat on the edge of a table, and puffed his cigar.

OW then! spit it out, Giglamps!" said little Mr. Bouncer, as he sat on the edge of a table, and puffed his cigar.

Thus encouraged, Mr. Verdant Green made a sudden and desperate plunge into the deep waters of his trouble. "I 've been persuaded to make a book."

"What! to come the literary dodge and do the complete author? Well! I did n't think it was in you, any more than rat-hunting is in a lamb. And what is it to be called? Is it to be the Whole Duty of Man style, as applied to Freshmen in general and Verdant Green in particular? or, is it to be some thing facetious, 'Grins by Giglamp,' or something of that sort? What 's the book about?"

"It 's about the Derby," said Mr. Verdant Green, with a heavy sigh.

"About the Derby! Oh! that 's the sort of book, is it? I see, now, which way the wind lies." Little Mr. Bouncer gave a meditative and prolonged whistle, which, being mistaken for a signal by Huz and Buz, immediately sent them on a vain quest for rats in every corner of the room. "A book about the Derby!" said the little gentleman, when, by the aid of thwacks from his post-horn, he had reduced his dogs to a deceitful tranquillity similar to that of a volcano before eruption; "why Giglamps, you could just as soon write 'Paradise Lost,' like that mute, inglorious Milton did."

"I 've lost my paradise—at any rate, my peace of mind," groaned Mr. Verdant Green, too occupied by his own thoughts to take notice of the false application of his friend's quotation.

"Tell me how it all came about, and I 'll see if I can help you," said little Mr. Bouncer, after some thoughtful pulls at his cigar. "Two heads are better than one, although mine 's but an addled one. The fact is, I 'd too much pap when I was a baby, and it got into my noddle. But, how was it?"

"You know Blucher Boots?—the Honourable Blucher Boots, son of Lord Balmoral?" added Mr. Verdant Green in explanation.

"Know him!" cried little Mr. Bouncer; "yes! who doesn't know him? Although he 's Honourable by name, he 's not by nature. He 's as genuine a cad as was ever pupped; and if some feller would give him a good licking, and take the conceit out of him, it would be a public benefit. And did he help you to make your book on the Derby, Giglamps?"

"He did," replied the other. "At least he made it all himself; for I did not understand anything about it. I never saw a horse-race, and have never been accustomed to read much about them; and I am quite ignorant about taking bets, and laying odds, and all that sort of things; so Blucher Boots undertook to make what he called a book for me."

"I see!" said little Mr. Bouncer; "it 's like the old rhyme—'Who 'll make his book? I, says the Rook.' And Blucher Boots is a regular rook. He 'd bet with his own grandmother, if he could, and would cheat her out of every penny if he could get on her blind side. He 's a nice young man for a small tea-party, I don't think. The less you have to do with him the better, Giglamps. Now let's hear all about it. Where did you tumble up against him?"

"I met Mr. Flexible Shanks, Lord Buttonhole's son, at Fosbrooke's wine party," replied Mr. Verdant Green, "and he very kindly asked me to come to his rooms, and I went; and there I met Blucher Boots, and he invited me to breakfast with him the next morning, and I accepted, and went."

"That little pig went to market, and this little pig stayed at home!" sang little Mr. Bouncer, in a voice that was almost too much for the feelings of Huz and Buz, who gave vent to their emotions by smothered growls. "It would have been better for you, Giglamps, if you stayed at home with this little pig—meaning me—and not have gone to Blucher Boots's breakfast."

"I went," said Verdant, simply, "because I thought it a great compliment to be invited to the rooms of two sons of noblemen, when I was not previously known to them, and was only a Freshman."

"Precisely!" rejoined little Mr. Bouncer, "I 'll say nothing against Flexible Shanks, for he 's a regular brick; but I expect it was because you were a Freshman that Blucher Boots asked you."

"But, at any rate, it was very friendly and polite of him to invite me to breakfast," argued Mr. Verdant Green, who would have wished it to be thought that the attentions of Lord Balmoral's son were due solely to his personal merits, and were not to be attributed to the fact of his being a Freshman.

"And so you went," said little Mr. Bouncer, "with the tear of gratitude in your eye, and a burst of loyalty in your bosom. Well, and what then? Cut along, my hearty."

"After breakfast," continued Verdant, "the men gradually went away; but he asked me to stop, and have a weed with him; and I did so, because I was all right for Lectures, having posted an Æger."

"Posted an Æger!" echoed Mr. Bouncer. "My gum, Giglamps, you 're coming it, for a Freshman. You pretend to be Æger, or sick and peaky, when you 're in robust health. And then, after your Æger breakfast where, of course, you behaved yourself like a sick man ought to do, and had nothing but tea and dry toast—what came next?"

"Then Blucher Boots and I were left alone, and he was very friendly and pleasant, and asked me about Warwickshire, and places that I knew; and his claret-cup was very nice; and he talked a good deal about horses and races, and the odds."

"Odd if he would n't!" said little Mr. Bouncer, puffing at his cigar; "I know his horsey proclivities. And then he offered to make your Derby book?"

"Well," replied Mr. Verdant Green—as people often do when they are speaking of something that is not at all well, but bad—"something like it. He told me that he had a friend who had been kind enough to tell him, quite in confidence, which horse is to win the Derby. It is not the favourite; but it is a horse that, at present, is not much talked about. He said it was a dark horse; but whether a black or a brown, I don't know."

Little Mr. Bouncer involuntarily winked his eye, and smiled, as though he would direct an imaginary companion's attention, and say, "Oh, here 's a go!" but his Freshman friend was too much engaged in his narrative to notice the action.

"And Blucher Boots' friend," continued Verdant, "has kept his eye on the horse for a long time, and has seen him tried on a private course, and is in a particular position to obtain correct information on the subject. And Blucher Boots himself has seen this dark horse, whose name I may tell you—but of course, in the strictest confidence."

"Of course! the very strictest of the strict, Giglamps! I 'll be as dark as the horse."

"His name is 'The Knight.'"

"That Knight ought to be ridden by Day, ought n't he? Oh, Day and Knight, but this is wondrous strange! as Shikspur says." And the countenance of little Mr. Bouncer, as he watched Mr. Verdant Green, was quite a study.

"And," continued that innocent gentleman, "Blucher Boots, to use his own expression; is sweet upon The Knight, and is firmly convinced that no other horse, not even the favourite, has the slightest chance to win the race from him. So that he is going to support him to the best of his ability, and said that he should put a pot of money on him—an expression that I do not fully comprehend."

"It means," explained Mr. Bouncer, "that the money he will bet on the dark horse will go to the pot—that is, will be all U. P. and done for; like classical parties, who, when dead, were burnt, and had their ashes put into pots or urns." The little gentleman knocked off the ash of his cigar, and asked, "And what did B. B., which stands for Bad Boy, do then?"

"Why, then he spoke about having made his book for the Derby, and that he had done it so cleverly, and on such a sure plan, that he must be a gainer even if The Knight did not win; although he thought such an event, was an impossibility. And then he offered to show me how to make a book; and I tried to comprehend him, but I could not do so; although I fear that I gave him to understand that his explanations were quite clear to me. And he rather confused me by referring to a sweep; and although I knew that, on a race-course, people must meet with all sorts of queer characters, yet I thought it rather odd that a nobleman's son should appear to be so familiar with a sweep. And he strongly advised me to do what seemed to me a very strange thing; and that was, to join him in a sweep."

Little Mr. Bouncer chuckled to himself, and said, "I suppose, Giglamps, you took him for a cannibal of the Fa-fe-fi-fo-fum species; and, if you did, old fellow, you'd not be very far off the mark; for Blucher Boots would pick your bones as clean as a chicken, and get every shilling out of your pocket. He 's so hard up that he can scarcely rub two half-crowns against each other, and a sovereign might dance in his pocket without breaking its shins. Did he get anything out of you?"

"I am sorry to say he did," sighed Mr. Verdant Green, with a retrospective glance at his past conduct. "He talked to me so much about my Derby book, and joining him in the sweep, and other things which I could not properly understand—and he put it to me in so many ways about the great advantages that I should secure by backing The Knight at long odds,—I think that was his expression—that, at last, when he asked me if I could oblige him with change for a five-pound note"—

"I 'm interrupting you," said little Mr. Bouncer; "but, did you see that five-pound note, Giglamps?"

"No; I did not."

"If you had, you would have seen what his creditors have not yet been privileged to witness, much less to handle," observed Mr. Bouncer. "Well, young 'un, go ahead!"

"And I told him that I could not change him the note; for, curiously enough, I myself wanted change for a five-pound note; my papa—I mean, my Governor—having, that morning, sent me, in a letter, three five-pound notes. And, when Blucher Boots asked if I had got the notes with me, I said 'Oh, yes!' and pulled them out of my pocket-book. And he said that they had been sent most opportunely, and that I could n't do better than to let him lay them out for me; and that they would bring me in ever so much more. And he, in fact—that is to say," stammered Mr. Verdant Green, as he somewhat hesitated to make a full disclosure of the truth, even to his friend—"in short—I—at last I handed them to him."

"What! you gave Blucher Boots the three five-pound notes? My gum, Giglamps!" Little Mr. Bouncer did not say much. Perhaps, like the monkeys, he thought the more. There was a silence for a few minutes. Mr.

Verdant Green sat in a dejected posture, with his head leaning upon his hand. Mr. Bouncer puffed savagely at his cigar; flung the stump out of the window; hit Buz abstractedly, yet sharply, with his post-horn, causing that canine monster to show his teeth in a highly threatening way; and, at length, said, "I don't wonder, Giglamps, that you look in a blue funk!"

Although Mr. Verdant Green attached very indefinite ideas as to the nature and sensations of a "blue funk"—a subject on which Gainsborough's "Blue Boy" might have been able to throw some light—yet, the phrase sounded ominously in his ears, and, if possible, plunged him yet deeper into the deep waters of his trouble.