Mexico, as it was and as it is/Journal of journey in the Tierra Caliente

JOURNAL OF A JOURNEY

IN THE

TIERRA CALIENTE:

BEING AN ACCOUNT OF A VISIT TO

CUERNAVACA, THE RUINS OF XOCHICALCO, THE

CAVERN OF CACAHUAWAMILPA, CUAUTLA

DE AMILPAS,

AND SEVERAL

MEXICAN HACIENDAS OR PLANTATIONS.

17th September, 1842. This is still the rainy season in the Valley of Mexico, and the clouds which have hung around the valley for some weeks past, pouring out their daily showers, seem to forbid our departure upon an expedition which I have contemplated making before I leave Mexico; but as the period of my departure is rapidly approaching, I find it necessary to embrace the opportunity presented by the protection of a party of gentlemen who design visiting, during the next two weeks, some of the most interesting portions of Tierra Caliente, south of the Valley of Mexico. It strikes me, too, that as the mountains which surround this valley are the highest in Mexico, it is more probable that the stormy clouds, driven up by the north winds from the sea, gather and are attracted by these heights, and consequently expend themselves over the dearest plains;—the adjoining valleys which are lower than this, are likely, therefore, to be free from the continual deluge of water with which we have been visited for the last two months.

Our preparations have accordingly all been made to set out to-day, about four o'clock.

ST. AUGUSTIN DE LAS CUEVAS.

At three o'clock the court-yard of our houses presented the appearance of a cavalry barrack;—saddles, sabres, pistol-holsters, huge spurs, whips, baggage, horses, and servants. By four o'clock we had all rendezvoused at the dwelling of Mr. G, in the Calle del Seminario. Our party is composed of seven, among whom are Mr. Black the American Consul, and Mr. Goury du Roslan, the Secretary of the French Legation; the rest are chiefly Scotch gentlemen, engaged in commerce in Mexico. Two mules have been hired and laden with a good store of provant—such as hams, corned- beef, portable soups, sausages, sardines, and wine, and these are put under the charge of an arriéro, who, with my servant, and two other servants of our companions, make up a company of eleven, all mustered.

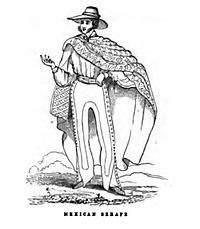

Few things can be more complete for all weathers and all seasons, than the outfit of a Mexican horseman. He has everything that can contribute to the comfort or necessity of the passing hour, strapped to some part of his horse or his usual equipments.

MEXICAN SERAPE

mexican horseman.

Thus mounted on his high-peaked Spanish saddle, with stiff wooden stirrups, over which are long ears of leather,—and his feet armed with the huge Spanish spur, to which is attached a small ball of finely-tempered steel, that strikes against the long rowels at every tread of the man or beast, and rings like a fairy bell,

you have a complete picture of a Mexican horseman, equipped at every point and ready for the road. If he has to fight, he has his weapons; if to feed, he has his laden mule; if it rain, he dons his serape and armas de agua, and rides secure from storm and wind; and if he arrives at an Indian hut, after a long and toilsome journey, and no bed is ready to receive him, he spreads the skins on the earthen floor—his saddle is his pillow, and his blanket a counterpane. He is the compendium of a perfect travelling household.

In this guise were most of us equipped when we mustered in the great square—except, that for leathern jackets, we had substituted blue cloth, and had strapped our serapes on the pillions behind us.

All were punctual to the minute, and the arriéro, together with Gomez, and Antonio, the two other servants, were sent on to the Garrita to pass our carga mules. Gomez was a stanch, wooden-faced old trooper, who had done good service in the troublous times in Mexico; Ramon, a Spaniard,—a thin, hatchet-visaged, boasting, slashing rogue,—who had fought through many a guerilla party of the Peninsular war; and Antonio, a sort of weazened supernumerary, with a game leg, a broken nose, a toothless upper gum, a devilish leering eye, and a pepper-and-salt cur as worthless as his master, who amused himself during the whole of our journey by running bulls, tearing sheep, worrying fowls, and taking twice as much exercise as was necessary.

A party in better spirits never set out. We had the prospect of relaxation, the sight of something novel, and the hope of propitious skies.

As the Cathedral clock struck four we put our animals in motion—sed vana spes! A cloud, which had been for some time threatening, opened its bosom. In a moment our serapes were on, the armas de agua tied round our waists, and the storm of wind and rain was upon us. We consoled ourselves by thinking it was only the baptism of the expedition.

At the city gate the guard of Custom-house officers wished to charge an export duty on our wine, but our passes from M. de Bocanegra and the Governor saved us, and we launched forth on the road to St. Augustin, with the shower increasing every minute. It is useless to say more of this dreary evening. For three hours the rain was incessant; and that the rain of a tropical storm, accompanied by wind and lightning. The water flowed from our blankets like spouts. The road over the plain was no longer a highway but a water-course, rushing and gurgling over every descent. The poor Indians returning from market paddled along, shrouded up in their petates. There was no conversation in the company. Every one was sulky, and felt a very strong disposition to return home and start fair with dry skies to-morrow; but it was decided to push on. Finally, one of our carga mules, with all the provant, tumbled over in the mud, and tried to kick himself clear from his load; the arriéro, however, was directly over him with his long whip, showering blows on head and haunches until he again set him in motion for the village.

It was quite dark when our cold, weary, and uncomfortable party entered St. Augustin, and knocked at the gate of Mr. M——'s country-house, where we were to stay for the night. We hoped to find everything duly prepared for our reception; and among our hopes, not the least was for a blazing fire to dry our bespattered garments. We came up to the door, one by one, silently and surlily. We were not only angry with the weather, but seemed to be mutually dissatisfied. After a deal of thumping, the door was slowly opened, and instead of the salutation of a brilliant blaze in the midst of the court–yard—one miserable, sickly tallow candle made its appearance! A colder, damper, or more uncomfortable crew never reunited after a storm; and we found, notwithstanding the usual protection of Mexican blankets, Mexican saddles, and armas de agua, that the rain had penetrated most of our equipments, and that we were decidedly damp, if not thoroughly drenched.

We entered the house after disposing of our accoutrements in a large hall, and found quite comfortable quarters and beds enough for all parties. A change of dress, a glass of capital Farintosh, (which was produced from the capacious leathern bottle of Douglas,) and a cut at the ham, with a postscript of cigars, set us all to rights again; and at eleven o'clock, as I write this memorandum, the party are singing the chorus of a song to Du Roslan's leading.

Sunday, 18th. I was asleep last night in five minutes, nor did I awake until aroused at 5 o'clock by the loud pattering of the rain against the shutters. Cold, gray, cheerlessly, the day broke; and as cold and cheerlessly did we assemble in the kitchen to take our chocolate. A council was held as to proceeding or waiting for better weather. I adhered to my theory, that the rain was confined to the Valley of Mexico; and that when we had passed the mountains in this day's journey, we would find it dry and pleasant travelling in the warmer and lower country. At any rate there was something consolatory in the hope. The horses were accordingly ordered, the damp dresses packed, our serapes wrung out, and the mules freighted for the day.

As the bells were ringing for mass, and the villagers hurrying through the streets to church, we sallied forth, every man trying to discover the symptom, even, of a break among the dreary brownish clouds that hung low from the mountain-tops to the valley.

As soon as the road leaves the town of St. Augustin, it strikes directly up the mountain, and runs over crags and ravines which in our country would startle the delicate nerves of a lady. Railroads and McAdam have spoiled us; but here, where the toilsome mule and the universal horse have converted men almost into centaurs and are the traditionary means of communication, no one thinks of improving the highways. But, of late years, diligences are getting into vogue between the chief cities of the Republic; and one, built in Troy, has been started on this very road. How it gets along over such ruts and drains, rocks and mountain-passes, it is difficult to imagine!

On we went, however, over hill and dale, the misty rain still drifting around us, and becoming finer and mistier as we rose on the mountain. The prospect was dreary enough, but in fine weather, these passes are said to present a series of beautiful landscapes. In front is then beheld the wild mountain scenery, while, to the north, the valley sinks gradually into the plain, mellowed by distance, and traversed by the lakes of Chalco and Tezcoco. Of the former of these we had a distinct view as the wind drifted the mist aside for a moment, when we had nearly attained the summit of the mountain. Here we passed a gang of laborers impressed for the army, and going, tied in pairs, under an escort of soldiers, to serve in the Capital. This was recruiting! Further on, we passed the body of a man lying on the side-path. He had evidently just died, and, perhaps, had been one of the party we had encountered. No one noticed him; his hat was spread over his face, and the rain was pelting on him.

We saw no habitations—no symptoms of cultivation; in fact, nothing except rocks and stunted herbage, and now and then, a muleteer, a miserable Indian plodding with a pannier of fruit to Mexico, or an Indian shepherd-boy, in his long thatch-cloak of water-flags, perched on a crag and watching his miserable cattle. We were then travelling among the clouds, near 9000 feet above the level of the sea.

INDIAN WITH PANNIER. INDIAN SHEPHERD

After about four hours' journey in this desolation, the clouds suddenly broke to the southward, revealing the blue sky between masses of sullen vapor, and thus we reached our breakfasting house on the top of the mountain.

Imagine a mud-hole, (not a regular lake of mud, but a mass of that clayey, oozey, grayish substance, which sucks your feet at every step,) surrounded by eight huts, built of logs and reeds, stuck into the watery earth, and thatched with palm leaves. This was the stage breakfasting station, on the road from Mexico to Cuernavaca! We asked for "the house;" and a hut, a little more open than the rest, was pointed out. It was in two divisions, one being closed with reeds, and the other entirely exposed, along one side of which was spread a rough board supported on four sticks covered with a dirty cloth. It was the principal hotel!

There was no denying that prospects were most unpromising, but we were too hungry to wait longer for food. We asked for breakfast, but the answer was the slow movement of the long forefinger from right to left, and a "No hai!"

"Any eggs?"

"No hai!"

"Any tortillas?"

"No hai."

"Any pulqué?"

"No hai."

"Any chilé?"

"No hai."

"Any water?"

"No hai!"

"What have you got then?" exclaimed we, in a chorus of desperation.

"Nada!"— nothing!

We tried to coax them, but without effect; and, at length, we ordered a mule to be unladen, and our own provisions to he unpacked. This produced a stir in the household, as soon as it became evident that there was to be no high bid for food.

In a moment a clapping of hands was heard in the adjoining room, and I found a couple of women at work, one grinding corn for tortillas, and the other patting them into shape for the griddle. There were two or three other girls in the apartment, and, taking a seat on a log, and offering a cigarrito to each of them, I began a chat with the prettiest, while the tortillas were cooking. A cigarrito, a-piece, exhausted, and with them, half-a-dozen jokes, I offered another to each of the damsels, and found them getting into better humor. At length, one arose, and after rummaging among the pots in a corner, produced a couple of eggs, which she said should be cooked for me. I thanked her, and by a little persuasion, induced her to add half a dozen more for the rest of the party. By the time that the eggs were boiled and the tortillas baked, I suggested that a dish of mollé de guagelote would be delicious with them, and felt sure that a set of such pretty lasses must know how to make it. "Quien sabe?" said one of them. "Was there not some left from this morning?" said another; and they both arose at once and looked again into the pots. The result was the discovery of a pan heaped with the desired turkey and chilé, and another quite as full of delicious frijoles. These were placed for five minutes over the coals, and the consequence was, that out of "Nada," I contrived to cater a breakfast that fed our company, servants, and arriéro, and which would have doubtless fed the mules also, if mules ever indulged in chilé. I never made a heartier meal, relishing it greatly in spite of the dirty table-cloth, the dirty women, the dirty village, and the fact that my respected tortilla-maker, while engaged in her laudable undertakings, had occasionally varied the occupation, by bestowing a pat on the cake, and another, with the same hand, on the most delicate portion of the leather-breeches of a brat who annoyed her by his cries and his antics. I shall long remember those girls, and the witchcraft that lies in a little good-humor, and a paper of cigarritos. Let no one travel through a Spanish country without them.

********

About one o'clock, we had again mounted, and riding along a level road which winds through the table-land of the mountain-top, we passed the Cruz del Marquez, a large stone cross set up not long after the conquest, to mark the boundary of the estate presented by Montezuma to Cortéz. At this spot the road is 9,500 feet above the level of the sea, and thence commences the descent of the southern mountain-slope toward the Vale of Cuernavaca. The pine forest in many places is open and arching like a park, and covers a wide sweep of meadow and valley. The air soon became milder, the sun warmer, the vegetation more varied, the fields less arid—and yet all was forest scenery, apparently untouched by the hand of man. In this respect it presents a marked difference from the mountains around the Valley of Mexico, where the denser population has destroyed the timber and cultivated the land.

This road is remarkable for being infested with robbers, but we fortunately met none. We were probably too strong for the ordinary gangs—some fifty shots from a company of foreigners, with double-barrel guns and revolving pistols, being dangerous welcome. At the village where we breakfasted, there was an ugly-looking band of scoundrels who hung around our party the whole time we remained there, watching our motions and examining our arms. I cannot conceive a set of figures better suited to the landscape that village presented, than these same human fungi who had sprung up amid the surrounding physical desolation, and flourished in moral rottenness. Every man looked the rascal, with a beard of a month's growth, slouched hats, from under which they scowled their stealthy side-glances, sneaking, cat-like tread, and muffled cloaks or blankets, that but badly concealed the hilts of knives and machetes. None of these gentlemen, however, pursued or encountered us.

After a slow ride during the afternoon, we suddenly changed our climate. We had left the tierras frias, and tierras templadas (the cold and temperate lands,) and had plunged at once, by a rapid descent of the mountain, into the tierra caliente where the sun was raging with tropical fervor. The vegetation became entirely different and more luxuriant, and a break among the hills suddenly disclosed to us the Valley of Cuernavaca, bending to the east with its easy bow. The features of this valley are entirely different from those of the Valley of Mexico, for although both possess many of the same elements of grandeur and sublimity, in the lofty and wide-sweeping mountains; yet there is a southern gentleness and purple haziness about this, that soften the picture, and are wanting in the Vale of Mexico, in the high and rarefied atmosphere of which every object, even at the greatest distance, stands out with almost microscopic distinctness. Besides this, the foliage is fuller, the forests thicker, the sky milder, and everything betokens the sway of a bland and tropical climate.

A bend of the road around a precipice, revealed to us the town of Cuernavaca, lying beyond the forest in the lap of the valley, while far in the east the mountains were lost in the plain, like a distant line of sea. Our company gathered together, on the announcement of the first sight of our port of destination for the night. It was decided, by the novices in Mexican travelling, that it could not be more distant than a couple of leagues at farthest; but long was the weary ride, descending and descending, with scarcely a perceptible decrease of space, before we reached the city.

In the course of this afternoon we passed through several Indian villages, and saw numbers of people at work in the fields by the road side. Two things struck me: first, the miserable hovels in which the Indians are lodged, in comparison with which a decent dog-kennel at home is a comfortable household; and second, the fact that this, although the Sabbath, was no day of repose to these ever-working, but poor and thriftless people. Many of the wretched creatures were stowed away under a roof of thatch, stuck on the bare ground with a hole left at one end to crawl in!

What can be the benefit of a Republican form of government to masses of such a population? They have no ambition to improve their condition, or in so plenteous a country it would be improved; they are content to live and lie like the beasts of the field; they have no qualifications for self-government, and they can have no hope, when a life of such toil avails not to avoid such misery. Is it possible for such men to become Republicans? It appears to me that the life of a negro, under a good master, in our country, is far better than the beastly degradation of the Indian here. With us, he is at least a man; but in Mexico, even the instincts of his human nature are scarcely preserved.

It is true that these men are free, and have the unquestionable liberty, after raising their crop of fruits or vegetables, to trot with it fifty or sixty miles, on foot to market, where the produce of their toil is, in a few hours, spent, either at the gambling table or the pulqué shop. After this they have the liberty, as soon as they get sober, to trot back again to their kennels in the mountains, if they are not previously lassoed by some recruiting sergeant, and forced to "volunteer " in the army. Yet what is the worth of such purposeless liberty or the worth of such purposeless life? There is not a single ingredient of a noble-spirited and highminded mountain peasantry in them. Mixed in their races, they have been enslaved and degraded by the conquest; ground into abject servility during the Colonial government; corrupted in spirit by the superstitious rites of an ignorant priesthood; and now, without hope, without education, without other interest in their welfare, than that of some good-hearted village curate, they drag out a miserable existence of beastiality and crime. Shall such men be expected to govern themselves?

*******

It was long after sunset when we descended the last steep, and passed a neat little village, where the people were sitting in front of their low roofed houses, from every one of which issued the tinkle of guitars. The bright sky reflected a long twilight, and it was just becoming dark when we trotted into Cuernavaca, after a ride of fourteen leagues.

Our companions had already reached the inn, and as we dashed into the court-yard, we found them à tort et à travers with the landlord about rooms. We had seen a flaming advertisement of this tavern and its comforts in the papers of the Capital, and counted largely on splendid apartments and savory supper after our tiresome ride and pic-nic breakfast. But, as at the "diligence hotel" in the morning—everything went to the tune of "No hai!" No hai beds, rooms, meats, soups, supper—nada! They had nothing! We ended by securing two rooms, and I set out to examine them, as well as my legs (stiff from being all day in the hard Mexican stirrups) would let me. The first room I entered was covered with water from the heavy rains. The second adjoined the first; and, although the walls were damp, the floor was dry; but there was no window or opening except the door!

We had secured the room, and of course wanted beds; because, room and bed, and bureau, and wash-stand, and towels, and soap, are not all synonymous here as in other civilized countries. Four of our travellers had fortunately brought cots with them; but I had trusted to my two blankets and my old habits of foraging. At length the master managed to find a bed for two more of us, and a cot for me, and thus the night was provided for. We had resolved not to go without supper, and my talents in that branch of our adventures having been proved in the morning, I was dispatched to the kitchen. I will not disclose the history of my negotiations on this occasion, but suffice it to say that in an hour's time we had a soup; a fragment of stewed mutton; a plate of Lima beans; a famous dish of turkey and peppers; and the table was set off by an enormous head of lettuce in the centre, garnished with outposts of oranges on either side, while two enormous pine-apples reared their prickly leaves in front and rear.

An hour afterward we had all retired to our windowless room, and titer piling our baggage against the door to keep out the robbers, I wrapped myself in my blanket, on the bare, pillowless, sacking-bottom, and was soon asleep.

Monday 19th September. The morning was exceedingly fine, the sun was out brightly, and there were no symptoms of the rain that had fallen during the night, except in the freshness it had imparted to the luxuriant vegetation of the valley.

Before breakfast I sallied forth for a walk over the town. Cuernavaca lies on a tongue of land jutting out into the lap of the valley. On its western side, a narrow glen has been scooped out by the water which descends from the mountains, and its sides are thickly covered with the richest verdure. To the east, the city again slopes rapidly, and then as rapidly rises. I walked down this valley street past the church built by Cortéz, (an old picturesque edifice, filled with nooks and corners,) where they were chanting a morning mass. In the yard of the Palace, or Casa Municipal, at the end of the street, a body of dismounted cavalry soldiers was going through the sword exercise. From this I went to the Plaza in front of it, at present nearly covered with a large wooden amphitheater, that had been devoted to bull fights during the recent national holydays. Around the edges of this edifice, the Indians and small farmers spread out their mats, covered with fine fruits and vegetables of the tierra caliente. I passed up and down a number of the steep and narrow streets, bordered with ranges of one-story houses, open and cool and fronted usually with balconies and porches screening them from the scorching sun. The softer and gentler appearance of the people, as compared with those of the Valley of Mexico, struck me forcibly. The whole has a Neapolitan air. The gardens are numerous and full of flowers. By the street sides, small canals continually pour along the cool and clear waters from the mountains.

At nine o'clock I returned to breakfast, and found it rather better than our last night's supper. While this meal was preparing, I strolled out into the garden back of the hotel.

The house once belonged to a convent, and was occupied by monks; but many years since it was purchased by a certain Joseph Laborde, who played a bold part in the mine-gambling which once agitated the Mexicans with its speculative excitement.

In 1743, Laborde came, as a poor youth, to Mexico, and by a fortunate venture in the mine of the Cañada del Real de Tapujahua, he gained immense wealth. After building a church in Tasco which cost him near half a million, he was suddenly reduced to the greatest misery, both by unlucky speculations, and the failure of mines from which he had drawn an annual revenue of between two and three hundred thousand marks. The Archbishop, however, permitted him to dispose of a golden soleil, enriched with diamonds, which, in his palmy days, he had presented to his church at Tasco; and with the produce of the sale, which amounted to nigh one hundred thousand dollars, he returned once more to Zacatecas. This district was at that period nearly abandoned as a mining country and produced annually but fifty thousand marks of silver. But Laborde immediately undertook the celebrated mine of Quebradilla, and in working it, lost again, nearly all his capital. Yet was he not to be deterred.

With the scanty remains of his wealth, he persevered in his labors; struck on the veta grande, or great vein of La Esperanza, and thereby, a second time, replenished his coffers. From that period, the produce of the mines of Zacatecas rose to near five hundred thousand marks a year, and Laborde, at his death, left three millions of livres. In the meantime, however, he had forced his only daughter into a convent, in order that he might bequeath his immense property unembarrassed to his son; who, in turn, infected like his father with religious bigotry, voluntarily embraced the monastic life, and ended the family's career of avarice and ambition.

During his days of prosperity, Laborde had owned the property on which we are now staying, and embellished it with every adornment that could bring out the beauties of surrounding nature. The dwelling is said to have been magnificent before it was destroyed during the Revolution, but nothing remains now of all the splendor with which the speculator enriched it, except the traces of its beautiful garden. This is situated on the western slope bending toward the glen, and contains near eight acres in its two divisions. These he covered with a succession of gradually descending terraces, filled with the rarest natural and exotic flowers. In the midst of these gardens is still a tank for water-fowl, and over the high western wall rises a mirador or bellevue, from which the eye ranges north, south, and west, to the mountains over the plain, which is cut in its centre by the tangled dell.

The northern division of this garden is reached by a flight of steps from the first, and incloses a luxuriant grove of forest trees, broad-leaved plantains, and a few solitary palms waving over all their fan-like branches. In these dense and delicious shades through which the sun, at noon, can scarcely penetrate, a large basin spreads out into a mimic lake. A flight of fifteen steps descend to it from the bank, and were once filled with jars of flowers. In the centre of this sheet two small gardens are still planted, and the flowers bending over their sides and growing to their very edge, seem floating on the waters. At the extreme end of the grounds, a deep summer-house extends nearly the whole width of the field on arches, and its walls are painted in fresco to resemble a beautiful garden filled with flowers and birds of the rarest plumage. Looking at this from the south end of the little lake, the deception is perfect, and you seem beholding the double of the actual prospect, repeated by some witchery of art.

I would gladly have spent the day in this garden, but we had arranged our journey so as to devote a portion of this morning to visit the adjacent hacienda of Temisco, a sugar plantation, owned by the Del Barrios, of Mexico. Accordingly, after breakfast we mounted, and passing down the steep descents to the east, we struck off into the fields in a southwardly direction.

The beautiful suburbs of Cuernavaca are chiefly inhabited by Indians, whose houses are built along the narrow lanes; and in a country where it is a comfort to be all day long in the open air under the shade of trees, and where you require no covering except to shelter you in sleep and showers, you may readily imagine that the dwellings of the people are exceedingly slight. A few canes stuck on end, and a thatch of cane, complete them.

But the broad-leaved plantain, the thready pride of China, the feathery palm, bending over them, and matted together by lacing vines and creeping plants covered with blossoms—these form the real dwellings. The whole, in fact, would look like a picture from Paul and Virginia—but for the figures! Unkempt men, indolent and lounging; begrimed women, surrounded by a set of naked little imps as begrimed as they; and all crawling or rolling over the filth of their earthen floors, or on dirty hides stretched over sticks for a bed. A handful of corn, a bunch of plantains, or a pan of beans picked from the nearest bushes, is their daily food; and here they burrow, like so many animals, from youth to manhood, from manhood to the grave.

*********

After leaving the city, our road lay for some distance along the high table-land, and at length struck into the glen which passes from the west of Cuernavaca, where, for the first time in Mexico, I actually lost the high-road. Imagine the channel of a mountain-stream down the side of an Alleghany mountain, "with its stones chafed out of all order, and many of them worn into deep clefts by the continual tread of mules following each other, over one path, for centuries. This was the main turnpike of the country to the port of Acapulco, and several of our party managed to continue on horseback while descending the ravine; but out of respect both for myself and the animal I bestrode, I dismounted, and climbed over the rocks and gullies to the bottom of the glen, where we crossed a swift stream on a bridge. Ascending from this to the ridge on the opposite side, in rather a scrambling manner, we entered the domain of the hacienda[1] of Temisco, the buildings of which we shortly reached after passing through an Indian village, where most of the laborers on

the estate reside.

This is one of the oldest establishments of note in the Republic, and passed, not many years since, into the hands of the present owners for the sum of $300,000. The houses (consisting of the main dwelling, a large chapel, and all the requisite out-buildings for grinding the cane and refining the sugar,) were erected shortly after the conquest, and their walls bear yet the marks of the bullets with which the refractory owner was assailed during one of the numerous revolts in Mexico. He stood out stoutly against the enemy, and mustering his faithful Indians within the walls of his court-yard, repulsed the insurgents.

indian hut in the tierra caliente.

We were received by Don Rafael, one of the brothers del Barrio, whom we unexpectedly met on the estate. He conducted us into a long monastic-locking hall, nearly bare of furniture, yet bearing traces of taste and refinement, in a well-selected library and valuable piano in one corner, while a hammock, suspended from the unplastered rafters, swung across the airy apartment. Here we were most hospitably entertained, and enjoyed a pleasant chat with the owner, in French, Spanish, English and German, all of which languages the worthy gentleman speaks,—having not only travelled in, but dwelt long and observingly in every country of Europe. It was strange, in these wild portions of Mexico, in the midst of Indians, to drop thus suddenly and unexpectedly by the side of a well-bred man, dressed in his simple costume of a plain country farmer, who could converse with you in most of the modern tongues, upon all subjects—from the collections of the Pitti Palace and the Vatican, to the breed and education of a game cock!

As we looked over the fields of cane, waving their long, delicate green leaves, in the mid-day sunshine to the south, he pointed out to us the site of an Indian village, at the distance of three leagues, the inhabitants which are almost in their native state. He told us, that they do not permit the visits of white people; and that, numbering more than three thousand, they come out in delegations to work at the haciendas, being governed at home by their own magistrates, administering their own laws, and employing a Catholic priest, once a year, to shrive them of their sins. The money they receive in payment of wages, at the haciendas, is taken home and buried; and as they produce the cotton and skins for their dress, and the corn and beans for their food, they purchase nothing at the stores. They form a good and harmless community of people, rarely committing a depredation upon the neighboring farmers, and only occasionally lassoing a cow or a bull, which they say they "do not steal, but take for food." If they are chased on such occasions, so great is their speed of foot, they are rarely caught even by the swiftest horses; and if their settlement is ever entered by a white, the transgressor is immediately seized, put under guard in a large hut and he and his animal are fed and carefully attended to until the following day, when he is dispatched from the village under an escort of indians who watch him until far beyond the limits of the primitive settlement.

Du Roslan and myself felt a strong desire (notwithstanding the inhibition,) to visit this original community, as one of the most interesting objects of our journey; but the rest of our party objecting, we were forced to submit to the law of majorities in our wandering tribe.

I observed, that on this hacienda the proprietors have introduced all the improvements in the art of making sugar, and obtained their horizontal rollers and boiling-pans from New-York. How they reached their places over the wretched roads, must ever remain a riddle to others but Mexican teamsters; and yet, after all the immense outlay of capital, in the purchase and improvement of this property, the proprietor complains bitterly, this year, of the difficulty of selling its produce, and the general depression of the times. With roads to transport his crop to market, and with ideas beyond the back of a mule as the only means of transportation, he would not be forced to complain long of stagnant trade and trifling profits. Peace, internal improvement, and native enterprise, unmolested by fiscal legislation, are what Mexico requires; and, until she obtains them, the planter may vainly expend his fortune in mechanical improvements.

******

We reached Cuernavaca about 8 o'clock, meeting on the way a number of muleteers, and Indians with their wives, returning from market. A gang of thieves, sent under a guard to the town prison, also passed us en the road.

We entered the city, through the delightful suburb of groves. The families of many of the better classes of the inhabitants were sitting under the shade of their porches, and it was impossible to avoid remarking the delicate beauty of the females.

Indolence is said to be the general characteristic of Cuernavaca; and, as in all fine climates, it is fatal to enterprise and industry. The temperature is too high for these virtues. Man wants but shade, shelter, and a gratified appetite, and there is no inducement to make the interior of dwellings either beautiful or attractive. Working in the open air fatigues—reading, within, makes them drowsy. They rise early, because it is too warm to lie in bed; they go to mass, for exercise in the cool and balmy morning air; they go to sleep after their meals, because it is too warm to walk about; and they go to vespers, to pass the time until the hour arrives for another meal, as preparatory to another nap! And this, between sleep, piety, and victuals, life passes aimlessly enough, in this region of eternal summer.

******

We lounged for an hour or two in Laborde's beautiful garden, watching the sunset over the western glen, and found it difficult to leave even for the promise of a dinner. While we had been on our morning visit to the hacienda, the diligence arrived from Mexico, and the hungry passengers, who had travelled since three o'clock almost without food, made a deep inroad in the larder. It required some energy to repair this havoc, and as our dinner had been ordered at six o'clock, I took occasion to pay my respects to the cook-maid. With the aid of a little cash and persuasion, I managed to preserve our own stores untouched until we penetrate farther into the country, where, in all likelihood, we will need them more.

After dinner, we took a walk by moonlight through the town. The night was as cloudless and serene, as one of our summer evenings by the sea-shore.

Antonio, the broken-nosed hero, and owner of the cur, proposed that we should go to see a fandango, at the house of one of the burghers, who was his friend. He led the way, through several streets, to a neat dwelling in the midst of a garden, where we found a row of elderly ladies strung on high-backed chairs against the wall, while a dozen young and pretty ones (by the light of a couple of starved tallow candles,) received the compliments of as many of the village beaux. Two or three musicians were seated in a corner strumming their bandalones and going through a half hour of preparatory tuning, while the company gathered. At length, when all had assembled, the schoolmaster—a veteran and a bachelor, the briskest and busiest man of the party—constituted himself master of ceremonies for the evening, and insisted on our joining in a contra dance, got up expressly for the strangers. Du Roslan and myself joined the dance, on my principle of "taking people as they are, and doing as they do," besides that I think it always in the worst taste to leave men, no matter how humble or poor they may be, under the impression that you have visited them as curiosities. After footing it through, we handed the servants a couple of dollars to bring in refreshments of "Perfect-love" and "Noyau" for the ladies, and something more likely to be relished by the gentlemen. This we understood was not contrary to the rules of "good society;"—so they sipped and became livelier. A couple took the floor—the lady with castanets and the man chanting an air to the guitar. Another pair followed their example, while the remainder formed a cotillon, to the twang of the rest of the instruments. The Cuernavacans seemed wide awake, for once at least, and we stole off quietly at midnight, in the midst of an uproar of music and merriment.

20th September. At four o'clock, day was just breaking and the moon still shining, when we passed through the suburbs of Cuernavaca. As we reached the highlands of the plateau, where the barranca breaks precipitously, the sun rose. There had been no rain during the night; the sky was perfectly clear, and in the distance lay the mountains of the southern Sierra, with the morning mists resting like lakes among their

folds.

Passing over the declivitous road we had traversed yesterday, we soon struck off to the right, near the hacienda of Temisco, and after crossing a deep ravine, rose to a still higher plateau, where we enjoyed a beautiful view of this splendid estate, with its white walls and chapel tower, buried in the middle of bright green cane-fields, waving with the fresh breeze in the early light.

From this eminence the guide (who was a half-breed Indian and Negro,) pointed out to me a small mountain, at the extremity of the plain in front, on which was situated the Pyramid of Xochicalco—the subject of our day's explorations. The cerro appears to rise directly out of the levels between two mountains, and the plain continuing to its very foot, might seemingly be traversed in half an hour. Accordingly, I expressed this opinion to the guide, and put my horse directly in motion for it; but the half-breed turned off to the right. I remonstrated, as the whole plateau appeared to be a perfect prairie, smooth and easily crossed; yet he insisted that in the straight forward direction, and, indeed, in all directions, it was cut by one of those vast barrancas, which, worn by the attrition of water for ages, break on you unexpectedly in the most level fields, forcing you frequently to tread back your path or to go miles around for a suitable crossing. The space in a direct line over these gullies may be no more than fifty yards before you strike the same level on the opposite bank—and yet to reach it, you are compelled to descend hundreds of feet and ascend again, among rocks and herbage for the distance of a mile. Such was the account of the barrancas, given by our guide, except that he declared the one in front of us to be at present entirely impassable. I submitted, therefore, to his advice, and turning off with him to the right, we trotted away at the head of our party, and soon lost sight of our lagging friends.

In a quarter of an hour we reached one of the barrancas of which he had spoken, and it fully justified his description:—a wide, yawning gulf in the midst of the plain, with precipitous sides tangled with rocks and shrubbery.

Although the path was scarcely broad enough for the horse's feet,—with a steep towering on the right, and a precipice of a hundred yards plunging down immediately on his left,—this bold rider never quitted his animal, but pushed right onward. I confess that I paused before I followed.

Two travellers, who passed us half an hour before, had already descended, and were thridding their way on the other side of the glen among the rocks. Instead, however, of taking the side of the opposite steep in a right line with the descent, as they ought to have done, they had followed the downward course of the stream in seeking for an easier rise, and they were forced to halt before a pile of impassable rocks, from which they shouted to our guide for directions.

When I again caught a glimpse of the half-breed, his head was rising and sinking with the motion of his horse, a hundred feet below me, as he slid along the shelving precipices of the barranca. Yet there was no alternative but to follow him; and as my horse was an old roadster in the tierra caliente, I resolved not to be outdone, and so, giving him his own time and control of the bridle, I trusted to his sagacity, and put him in the path. Nor had I occasion to regret my confidence in the beast; he did his work bravely, feeling his path, leaning against the upper sides of the dangerous passes, and clambering along with the tenacity of a fly and the activity of a cat. But when we were within fifty feet of the bottom of the ravine, a sharp turn to the right disclosed to me an almost headlong wall of rock for the remaining distance, into which steps had been cut that seemed scarcely passable on foot. I looked about me, and found there was room to dismount. Although I had great confidence in the horse, I confess to more in my own feet ; and thus scrambling on ahead, at the length of my lasso, I led the animal to the bottom of the dell, through which ran a broad and rapid stream swollen by the recent rains. Here I found the guide waiting for me. We plunged in at once, and partly swimming the horses and partly scrambling over the huge stones that formed the bed of the torrent, we attained the western bank in safety.

Fairly past one difficulty, another confronted us in the ascent of the opposite side, which seemed steeper and more craggy than the other. Determined to try my horse's mettle, I now continued on his back, and prepared him for what he had to expect by leaping a stone-wall at the foot of the declivity. He took at once nimbly to the crags, sprang after the guide from rock to rock and ledge to ledge, almost at a run; neither laid his ears to his neck for a moment, nor faltered for whip, spur, or word of encouragement; and, in half the time occupied in the descent, placed me on the top of the plateau.

But our companions were missing. From our elevated position, we commanded an uninterrupted view over the levels of the opposite prairie, yet they were neither on it, nor winding down the sides of the glen. Mr. Black soon made his appearance, and followed us up the cliffs; but he was not able to account for the rest of the party. In half an hour, however, they appeared near a mile up the barranca fording the river; and as it was evident that they were in the right direction and saw us, we pushed on. Descending another fold of the ravines, and again crossing an arm of the same stream, and zig-zagging another hill to its summit, we found ourselves at last on the table-land without the interruption of more barrancas.

Here we were rejoined by some of the party, who reported one of the mules to be broken down. The other, however, soon reached us, and it was sent back unladen, for the carga of the useless beast that was detained at the foot of the last declivity.

In half an hour we were again in motion, after a fruitless effort to shoot a young buck we had started in a neighboring corn-field. The sun was now intensely hot, and from its influence and the exercise of the morning, I was drenched with perspiration, nor was it disagreeable to find the pores of the skin thus relieved, after a residence of eight months in the Valley of Mexico, where the sensation is scarcely known.

I put up my umbrella to screen myself as much as possible from the direct rays, but the heat was reflected as scorchingly from the naked plain and shrubless hills. Nevertheless, wearied by the fatigue of six hours in the saddle without food, I soon fell into a doze, which lasted until we entered the bare gorge between the hills through which commences the ascent to the ruined pyramid.

Here, among some scanty bushes which afforded shade and shelter, we dismounted to breakfast; but, unluckily, water had been entirely forgotten by our servants ; there was not a drop in the gourds or canteens. Our pic-nic feast of sardines, ham, sausage, and corned. beef, consequently but added to a parching thirst which there was no hope of allaying but by slow draughts of claret and sherry that had been exposed for hours to a blazing sun on the backs of mules. Nor was this all. Scarcely had we seated ourselves, when clouds of black-flies and mosquitos came down from their nests among the ruins, and I write this memorial of them with hands inflamed by their inexorable stings.

In a bad humor, as you may naturally suppose, for antiquarian researches, I nevertheless mounted my horse as soon as breakfast was over, and ascended the hill with Pedro, while my companions, who had less anxiety about such matters, laid down under an awning of serapes stretched from tree to tree, to finish the nap that had been interrupted at half-past three in the morning.

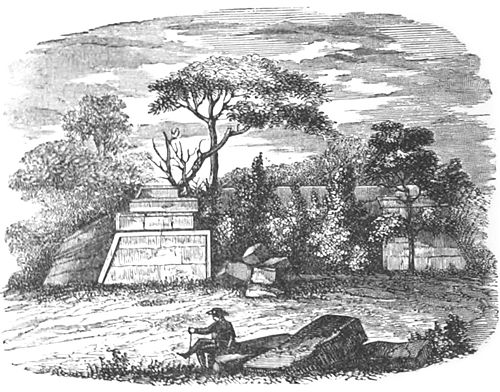

THE RUINS OF THE PYRAMID OF XOCHICALCO.

At the distance of six leagues from the city of Cuernavaca lies a cerro,

three hundred feet in height, which, with the ruins that crown it, is known

by the name of Xochicalco, or "the Hill of Flowers." The base of

this eminence is surrounded by the very distinct remains of a deep and

wide ditch; its summit is attained by five spiral terraces; the walls

that support them are built of stone, joined by cement, and are still quite

perfect; and, at regular distances, as if to buttress these terraces, there

are remains of bulwarks shaped like the bastions of a fortification. The

summit of the hill is a wide esplanade, on the eastern side of which are

still perceptible three truncated cones, resembling the tumuli found among

many similar ruins in Mexico. On the other sides there are also large

Northwest Corner of Xochicalco.

ruins of xochicalco.

The stones forming parts of the conical remains, have evidently been shaped by the hand of art, and are often found covered with an exterior coat of mortar, specimens of which I took away with me as sharp and perfect as the day it was laid on centuries ago.

Near the base of the last terrace, on which the pyramid rises, the esplanade is covered with trees and tangled vines, but the body of the platform is cultivated as a corn-field. We found the Indian owner at work in it, and were supplied by him with the long-desired comfort of a gourd of water. He pointed out to us the way to the summit of the terrace through the thick brambles; and rearing our horses up the crumbling stones of the wall, we stood before the ruins of this interesting pyramid, the remains of which, left by the neighboring planters after they had borne away enough to build the walls of their haciendas, now lie buried In a grove of palmettos, bananas, and forest-trees, apparently the growth of many hundred years.

Indeed, this pyramid seems to have been (like the Forum and Colliseum at Rome,) the quarry for all the builders of the vicinity; and Alzate, who visited it as far back as 1777, relates, that not more than twenty years before, the five terraces of which it consisted, were still, perfect; and that on the eastern side of the upper platform there had been a magnificent throne carved from porphyry, and covered with hieroglyphics of the most graceful sculpture. Soon after this period, however, the work of destruction was begun by a certain Estrada, and it is not more than a couple of years since one of the wealthiest planters of the neighborhood ended the line of spoilers by carrying off enormous loads of the squared and sculptured materials, to build a tank in a barranca to bathe his cattle! All that now remains of the five stories, terraces, or bodies of the pyramid, are portions of the first, the whole of which is of dressed porphyritic rock, covered with singular figures and hieroglyphics executed in a skillful manner. The opposite plate presents a general view of the ruins as seen from the westward.

The basement is a rectangular building, and its dimensions on the northern front, measured above the plinth, are sixty-four feet in length, by fifty-eight in depth on the western front. The height between the plinth and frieze is nearly ten feet; the breadth of the frieze is three feet and a half, and of the cornice one foot and five inches. I placed my compass on the wall, and found the lines of the edifice to correspond exactly with the cardinal points.

The western front is quite clear of bushes and fallen stones, and we had an opportunity to examine minutely the sculpture of the northwestern corner, which is very accurately delineated by Nebel[2] in the second engraving.

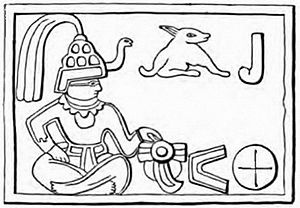

In the left-hand corner of this sculpture will be perceived the head of a monstrous beast, whose bearded and open jaws are armed with sharp teeth, from between which protrudes a forked tongue. In front of this is a crook or staff, terminated by a plume of feathers, similar to that of the head-dress of the figures that will be subsequently described. Beneath the mouth of the monster is a square, resembling a hieroglyph, or perhaps a Chinese letter; and below this is a rabbit, a figure which will be noticed again on the corner stone that formed part of the base of the second story, as well as on the frieze of the first.

Nothing of this pyramid remains so uninjured as the northern front; and this, with the exception of parts of the frieze and cornice, still entire. I present, in the plate marked A, a copy of the drawing made of it by Alzate at the period of his visit in 1777.

It will be perceived, that although the figures at the corners somewhat resemble those already described on the western front, yet the lines proceeding from the mouths of the monsters' heads fall in a curve; and it was doubtless from these that the story repeated by Humboldt originated, that "at the Pyramid of Xochicalco there were representations of crocodiles spouting water." They certainly are not crocodiles, but more probably, some fabulous monsters fashioned from the imaginations of the unknown builders, or compounded, perhaps, of various symbols by which they represented their deities.

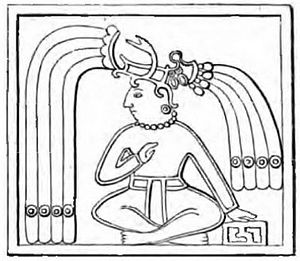

On the frieze are constantly repeated the figures represented by Nebel in the following drawings :

The figures in both of these bassi-relievi are seated cross-legged; plumes depend from a cap of the one, and from an odd head-dress of the other; and the left hand of the figure in the second drawing rests upon an ornament or symbol. In the figure of the first drawing the right hand is placed on the thigh; the left holds a sort of crooked dagger, and a curious bandage, not unlike a pair of spectacles, is over the eyes. Four symbols cover the rest of the square—a rabbit, a figure precisely like the letter J, another like the letter V, on its side, and an oval in which there is a cross. These relievos, as I before observed, run round the whole of the remaining frieze, while the cornice above it is sculptured with the tasteful ovals represented in the drawing of the northwestern angle.

I could not find any remains of color on the sculpture, which is generally between three and four inches deep. I have represented the outlines of the stones of which the edifice is composed in the design of the north-western angle. They are laid upon each other without cement, and kept in place by their weight alone; and as the sculpture of a figure is seen to run frequently over several of them, there can be no doubt that the bassi-relievi were cut after the pyramid had been erected.

Some idea may be formed of the immense labor with which this building was constructed, from measurements I made of several of the masses of porphyry that compose it. The whole building occupies a space of three thousand seven hundred and twelve square feet—the middle stone in the first story at the north end, is seven feet eleven inches long, and two feet nine inches broad; the stone at the northeast corner on the second story, represented in the plate as bearing the figure of a rabbit, is five feet two inches long, and two feet six inches broad; and the stone at the base of the southwest corner is two feet seven inches high, five feet long, and four feet seven inches broad.

When it is recollected that these materials were not found in the neighborhood, but were brought from a great distance, and borne up a hill, (more than three hundred feet high,) we cannot fail to be struck with the industry, toil and ingenuity of the builders, especially as the use of beasts of burden was at that time unknown in Mexico. Nor was this edifice on the summit the only portion of the architect's labor. Huge rocks were brought to form the walls supporting the terraces that surrounded the hill a league in circumference, and the whole of that immense mass was cased in stone. Beyond these terraces again, there was still another immense task in the ditch, of even greater extent, which had to be dug and regularly embanked! When you combine all these difficulties and all their labors, I think you will agree with me, that there are but few works, not of essential utility, undertaken in the present age by civilized nations, that do not sink into insignificance when contrasted with the hill of Xochicalco, from whose summit towered its lofty pyramid of sculptured porphyry.

There appears to be no doubt that a flight of steps rose on the western front from the commencement of the terrace, and terminated before three portals, the remains of which Nebel alleges he discovered; but since his visit, the edifice has been so much injured, and the vegetation has sprung up so vigorously, that I was unable to perceive any indications of the apertures. It is probable that these led to the interior of the Temple, whence there was a communication with the subterranean vaults that have been explored within a few years by persons acting under orders of the Government. I endeavored to examine these underground apartments as soon as I found the opening to them, at the foot of the first terrace on the northern side of the hill; but the guide professed ignorance of the interior, and the Indian he had engaged to pilot me failed in attending. Indeed, such is the superstition of these simple-minded people, that you find it difficult to investigate anything in which their services are required, among the relics of their ancient race. They believe that the mounds and caverns are haunted by the spirits of their ancestors—that they were places of sepulture or holiness—and few have the hardihood to assist in revealing their secrets.

In examining various works on the subject of these ruins, the best notice I have found of them is the account of a visit of certain gentlemen in March, 1835, by order of the Supreme Government.[3] In making a complete examination, both of the pyramid and the hill, this party explored the caverns and vaults.

After describing their course through various dark and narrow passages, the walls of which were covered with a hard and varnished gray cement, that preserved its lustre in a remarkable degree, they came to two enormous pillars, or rather two masses, cleft from the rock of which the hill is composed, affording three entrances, between them, to a saloon near ninety feet in extent. Above them was a cupola of regular shape, supported by cut stones disposed in circles, in the middle of which was an aperture reaching perhaps to the summit of the pyramid. The writer describes the stones that compose the cupola as "diminishing gradually in size as they rise to the top, and forming a beautiful mosaic." It is much to be regretted that these explorers made no drawing of the spot, as it would be most interesting to see the outline of what we are thus led to believe is a regular arch; and it is equally to be regretted, that the superstitions of the Indians and the fear of wild beasts, scorpions and serpents, that are said to fill these sombre crypts, prevent a more extended examination of the interior of the hill. I was alone deterred by the haste of my companions, from delaying, at least another day, and devoting it to the exploration of these vaults.

There is a tradition among the Indians, related by Alzate, that when the pyramid still numbered its five stories, there was on, or near, the hill of Xochicalco, an enormous stone or group, representing a man whose entrails an eagle was tearing; but of this there are now no vestiges. Nebel states, that there was undoubtedly a communication from the interior of the temple to the vaults below; and, founding his belief on Indian tradition and on a discovery he made at the top of the first terrace, he alleges, that an aperture extended from the summit of the pyramid to the crypt we have described, and immediately beneath it was placed an altar, on which the sun's rays fell when that luminary became vertical. What his authorities were it is difficult to determine; but I imagine the tale to be quite as fanciful as many other portions of his beautiful work.

This gentleman has given a drawing of what he terms the "Restoration of the Pyramid of Xochicalco," as it is supposed to have appeared when its terraces were all complete; and although I do not believe he has sufficient authority for the figures with which he adorned the upper stories of the edifice, I have adopted his ideas generally in the following drawing, with the exception of adding a frieze and cornice to each of the stories, as will be seen, also, hereafter, in the outlines of the "Pyramid of Papantla."

restoration of the pyramid of xochicalaco.

Such, in all probability—from the authority of unimpeachable traditions, and the remains now crumbling to ruins and overgrown with the forest at its base—such, was the Pyramid of Xochicalco, when it first rose aloft covered with its curious symbols of mystic rites, and received from the Indian builders its dedication to the gods, or to the glory of some sovereign whose bones were to moulder within. Who those builders and consecrators were no one can tell. There is no tradition of them or of the temple. When first discovered, no one knew to what it had been devoted, or who had built it. It had outlasted both history and memory!

But no matter who built, or what nation used it as temple or tomb, those who conceived and executed it were persons of taste, refinement and civilization; and I venture to assert, that no one who examines the figures with which it is covered, can fail to connect the designers with the people who dwelt and worshipped in the palaces and temples of Uxmal and Palenque.

Fragmentary fragment as this pyramid is, it may still be deemed in outline, material, carving, design, and execution, one of the most remarkable of the antiquities of America. It denotes, besides, an ancient civilization and architectural progress, that may well entitle the inhabitants of our Continent to the character of an Original race. On the other hand, (for those who are fond of tracing resemblances, and believe that whatever there was of art, science, or cultivation among the aborigines, came from the "old world,") there is much in the shape, proportions and sculptures of this pyramid, to connect its architects with the Egyptians.

*******

The day was far advanced, when I stood for the last time on the corner, stone of the upper terrace and looked at the beautiful prospect around me. It was the centre of a mighty plain. Running due north were the remains of an ancient paved road leading over prairie and barranca to the city,[4] distinctly visible at the foot of the Sierra Madre—and, all around, at the distance of some miles, east, west, and south, rose lofty mountains, among whose valley-folds nestled the white walls of haciendas that owed their strength and massiveness to the spoliation of the very ruins on which I stood. Palace, temple, tomb, fortification, whatever it was, (and to all these uses has it been appropriated by the guessing tribe of antiquarians,) the Pyramid of Xochicalco was nobly situated in its day and generation, and no one will now visit its crumbling remains without a better opinion of the unfortunate races who were pushed aside to make room for the growth and expansion of European power.

*******

TETECALA.

It was near three o'clock, when we again took up our line of march under a burning sun; and, lingering with Pedro until after my companions had departed, I found, on reaching the bottom of the hill, that they were already out of sight, and that all traces of them were lost on the path among the trees and bushes. I shouted—but there was no answer. I inquired at the first Indian hut I passed, but no travellers had gone that way; and, although following a distinct and apparently straight, forward road, I acknowledge that I was lost. To add to my disquietude, I had forgotten the name of the village at which we were to lodge. It was useless, however, to sit down in the forest, and I therefore resolved to push onward with confidence that the path led somewhere. I had not gone more than half a mile when I came up with another straggler of our party—lost, like myself—and we trotted along side by side, occasionally shouting for our companions, and then halting a moment to take breath in the close and sultry air filled with clouds of mosquitos and flies that settled on our hands and faces as soon as we drew our bridles.

Suddenly, our road terminated at the margin of a wide stream, which was swollen over its banks by the late heavy rains, and was dashing along with the rapidity of a mill-race. On the opposite shore the road again reappeared, and we judged that this was of course the ford.

Pedro, who was mounted on a stout, long-legged animal, was sent ahead, and partly swimming his animal and partly wading, he reached the bank in safety. I immediately followed, but my horse was both short limbed, and weary from the exertions he had made in the morning. Scarcely had the water risen above his girth when he was off his legs. I kept his head toward the opposite shore, and as much against the stream as possible; but with all his efforts he could make no headway, and was swept bodily down by the current toward a wreck of broken trees and branches that bent over the water from the bank we had quitted. I spurred, whipped, encouraged him, without avail. He made another effort; but failing in that, kept his head above water and resigned himself to the tide. I felt my situation to be dangerous, especially as I was rapidly approaching the long and sharp branches, by which I knew that I should be severely injured. I resolved, therefore, to leap off and swim for the bank, which was not more than a dozen paces distant. But, at that moment, Pedro galloped down to the point opposite which I was drifting, and, as I was about executing my purpose, I saw his lasso, flung with great accuracy, settle around my animal's head. With the end wound round his saddle-bow, Pedro stood firmly on the shore, and, in a minute, the action of the current had swung my horse on soundings. Drenched as I was, I shall ever hereafter feel a debt of gratitude to a lasso—which is rarely felt for anything in the shape of a noose.

My companion and myself continued our journey, both wet, (for he had fared not much better than myself,) but both gratified with our drenching, as it had the effect of a bath, while the evaporation of the water from our soaking clothes, cooled and refreshed us.

Thus through valley and glade, (rarely meeting an Indian or passing one of their miserable houses,) and without intelligence of our party, we pushed onward until about six o'clock in the evening, when we reached a wide and cultivated plain, traversed by a considerable stream, resembling in its verdant banks and soft meadows set in a frame of lofty mountains, the scenery about the sources of our Potomac. We had not long journied over this plain before we passed the hacienda of Miacatlan. At a short distance, to the right of it, appeared the village of Tetecala. As soon as a passing Indian mentioned the name, we recollected it to be that of our halting-place for the night.

We speedily passed an Indian suburb, buried, as usual throughout the tierra caliente, in flowers and foliage, among which lounged the idle and contented population. Here we were met by a guide, who had been sent forward by our courteous entertainers, and we were soon under the shelter of their friendly roof.

Our horses were quickly unsaddled and bounding over the wide corral; and refreshed by a clean suit and a cigarrito, I had strolled over the tasteful village, and visited the market and the church (one of the neatest I have seen, especially in the simple and true taste of its architecture, and the arrangement of the altar and the pulpits,) before our companions made their appearance. It turned out, after all, that they—not we—had mistaken the road, and had wandered much out of their way under the direction of a guide. It is better sometimes to have none.

In addition to all our antiquarian researches, to-day we have travelled nearly fifteen leagues, and although I have earned a right to a soft pillow and bed, yet as there are none of these comforts in the house for me, I wrap myself in my serape on the hard settee, with full expectation of a night of sound repose.

*******

21st September—Wednesday. We left Tetecala rather late this morning, without other refreshments than a cup of chocolate and a biscuit, as our intention was to stop at the hacienda of Cocoyotla, where we arrived about 11 o'clock.

We had no letter of introduction to Señor Sylva, the proprietor; but we were, nevertheless, most kindly received by him. He requested us to dismount, and to amuse ourselves by inspecting his garden and orange-grove while he ordered breakfast.

This is a small, but one of the most beautiful estates in the tierra caliente. A handsome chapel-tower has recently been added to the old edifice; a wing on broad arches has been given to the dwelling, and the garden is kept in tasteful order.

Back of the house and bordering the garden, sweeps along a sweet stream, some twenty yards in width, and, by canals from it, the grounds are plentifully supplied with water. But the gem of Cocoyotla is the orangery. It is not only a grove, but a miniature forest, interspersed with broad-leaved plaintains, guyavas, cocos, palms, and mammeis. It was burthened with fruits; and a multitude of birds, undisturbed by the sportsman, have made their abodes among the shadowy branches.

We sauntered about in the delicious and fragrant shade for half an hour, while the gardener supplied us with the finest fruits. We were then summoned to an excellent breakfast of several courses, garnished with capital wine.

When our repast was concluded, Señor Sylva conducted us over his house; showed us the interior of the neat church, where he has made pedestals for the figures of various saints out of stalactites from some neighboring cavern; and finally dismissed us, with sacks of the choicest fruit, which he had ordered to be selected from his grove.

RANCHO DE MICHAPAS.

P. M. Our journey from this hacienda was toward the Cave of Cacahuawamilpa, which we propose visiting to-morrow, and we have reached, to-night, the rancho of Michapas.

This is a new feature in our travels. Hitherto we have been guests at haciendas and comfortable town dwellings, but to-night we are lodged in a rancho—small farmer's dwelling—an Indian hut.

We arrived about five o'clock, after a warm ride over wide and solitary moors, with a back ground of the mountains we passed yesterday. In front another Sierra stretches along the horizon; and in the foreground of the picture, a lake, near a mile in circuit, spreads out its silver sheet in the sunset, margined with wide-spreading trees and covered with water-fowl.

The house is built of mud and reeds, matted together; that is, there are four walls without other aperture but a door, while a thatch, supported on poles, spreads on either side from the roof-tree, forming a porch in front. This thatch is not allowed to touch the top of the walls, but between them and it, all around the house, a space of five or six feet has been left, by means of which a free circulation of air is kept up within. The interior (of one room,) is in perfect keeping with this aboriginal simplicity. Along the western wall there are a number of wretched engraving of saints, with inscriptions and verses beneath them; next, a huge picture of the Virgin of Guadalupe, with tarnished gilded rays, blazes in the centre; and near the corner is nailed a massive cross, with the figure of our Saviour apparently bleeding at every pore. A reed and spear are crossed below it, and large wreaths and festoons of marigolds are hung around. Six tressels, with reeds spread over them, stand against the wall; and in one corner a dilapidated canopy, with a tattered curtain, rears its pretentious head to do the honors of state-bedstead. The floor is of earth, and, in a corner, are safely stowed our saddles, bridles, guns, pistols, holsters, swords and spurs; so that taking a sidelong glance at the whole establishment, you might well doubt whether you were in a stable, church, sleeping-room or chicken-coop!

Don Miguel Benito—the owner and proprietor of this valuable catalogue of domestic comforts—received us with great cordiality. He is a man some fifty years of age; delights in a shirt, the sleeves of which have been so long rolled up, that there is no longer anything to roll down and a pair of those elastic leather- breeches that last one's life-time in Mexico, and grow to any size that may be required, as the fortunate owner happens to fatten with his years. Not the least curious part of Don Miguel's household, is his female establishment. He appears to be a sort of Grand Turk, as not less than a dozen women, of all colors and complexions, hover about his dwellings, while at least an equal number of little urchins, with light hair and dark, (but all with an extraordinary resemblance to the Don,) roll over the mud floors of the neighboring huts, or amuse themselves by lassoing the chickens.

G, the caterer of our mess, thought it but a due compliment to Don Miguel, who does not disdain to receive your money, to order supper—though we resolved to fall back in case of necessity upon our own stores, and accordingly, unpacked some pots of soup and sardines.

In the course of an hour, a board was spread upon four sticks, and in the middle of it was placed a massive brown earthen platter, with the stew. At the same time, a dirty copper spoon and a hot tortillia were laid before each of us. Although we had determined to hold ourselves in reserve for our soups, yet there was but little left of the savory mess.

Our turtle, flanked with lemons and claret, then came into play; and the repast was ended by another smoking platter of the universal frijoles.

Wild and primitive as was the scene among these simple Indians, I have seldom passed a pleasanter evening, enlivened with song and wit. When we crept to our reed tressels and serapes, at eleven o'clock, I found that the state-bed was already occupied by a smart-looking fellow from the West Coast, (who I take to have been rather deeply engaged in the contraband) and his young wife—a lively looking lass, rather whiter than the rest of the brood—who had spruced herself up on our arrival. Twelve of our party lodged together in that capacious apartment, while Don Miguel betook himself, with the rest of his household, to mats under the porch.

22nd September. It rained heavily last night, but the morning, as usual, was fresh, clear and warm. After a cup of chocolate, we sallied forth toward the Cave of Cacahuawamilpa, having previously dispatched our arriéros with the mules to Tetecala, to await our return on our journey toward Cuautla.

Our forces this morning were increased by the addition of some twelve or thirteen Indians, who had been engaged by Don Miguel to accompany us as guides to the cavern. They bore with them the rockets and torches which were to be burned within, and a large quantity of twine for thridding the labyrinth.

Leaving the lake, situated on the very edge of the table-land, we struck down a deep barranca, at the bottom of which our horses sunk nearly to their girths at every footstep, in an oozy marsh, that had not been improved by last night's rain. But passing these bogs, we ascended a steep line of hills, whence there was a splendid view of the snow-capped volcanoes of Puebla, and soon reached the Indian village of Totlawamilpa, where it was necessary to procure a "license" to visit the cavern, or, in other words, where the authorities extort a sum of money from every passenger, under the plea of keeping the road open, and the entrance safe. As we had special passports from the Mexican Government to go where we pleased in the tierra caliente I thought this precaution unnecessary, but our Indians refused to budge a peg without a visit to the Alcaldé; and therefore, while some of the party entered a hut, and set the women to cooking tortillias, others proceeded with the passports to the civic authorities.

We found the Alcaldé to be a stout old Indian, in bare feet, shirt sleeves, skin trowsers, and nearly as dark as an African. He was enjoying his leisure by a literary conversation with the schoolmaster who was his secretary, and the two were discovered in the midst of a host of ragged boys from eight to sixteen years old, seated on benches and learning their letters.

The moment we appeared, the Alcaldé rose to receive us with great dignity, and handing the passport to his secretary, he listened attentively while he heard that Mr.—— and Mr.——, of the Diplomatic Corps, were fully authorized by the Supreme Government to travel wheresoever they pleased without let, hindrance, or molestation from any of the good citizens of the Mexican Republic. When the secretary had concluded the document, and the Alcaldé had looked at it—upside down— and they had examined the signature of Vieyra and Bocanegra, and expressed themselves perfectly satisfied of their genuineness, they retired to a corner for consultation.

"The Señores," said the Alcaldé, turning to me, "wish to see the cavern, and they have permission from the Alcaldés and Chiefs in Mexico to go where they please;—this is true; but that liberty does not to the Cave of Cacahuawamilpa, which is under ground, while the passport relates only to what is above! The Señores must have a license from the prefect here, and, moreover, they must pay for it."

I told him that the Diplomatic Corps never paid for any such permissions. He shrugged his shoulders and said that might be, and no doubt was all very true in the city of Mexico, but that it was not the custom here; "los diplomaticos must fare like other people and pay for a license."

I thought of Stephens and his "broad seal;" and I produced my passport from the Department of State with the coat of arms of the United States, and the signature of Mr. Webster; but it was all Hebrew to the scribe; the eagle was not the Mexican eagle, and "Webstair," he had never heard of. He shook his forefinger from right to left, as if intimating that it was all a humbug, and that no such man was ever known in Mexico. They were old stagers in the matters of fees, and strangers did not drop down on such visits every day of the year!

While this by-scene was going on, the school exercises were, of course, suspended, and the pupils, with staring eyes and gaping mouths, listened to the discussion. At length, as time was rapidly passing, the Alcaldé was asked how much he wanted, and told that we would give him no extravagant sum. He named, I believe, ten dollars as his price, but we compromised for five—two of which were for the prefect, two for himself and one for the secretary. As I was anxious to get the autograph of so distinguished a functionary, I asked him for a written license; but he replied that it was not necessary. "You may go now," said he; "no one will molest you;" and turning to our guide: "The Señores are muy caballeros; " (which may be translated, "very gentlemen") "take care of them, and at your peril, see that they come back safely."

The secretary made a bow—the Alcaldé another—our guide led the way, and we rejoined our party at the Indian hut, where they had half a dozen women baking tortillas as fast as they could pat them, for our breakfast at the cave.