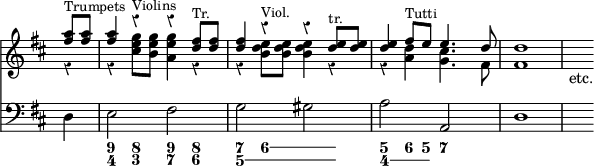

passAges of the most advanced character: notably one, beginning at the eighth bar of the introductory Symphony, in which the Discords struck by the Trumpets are resolved by the Violins, and vice versa, with a boldness which has never been exceeded.

It would be difficult to find two passages more unlike each other, in detail and expression, than this, and the alternate Chords for Stringed and Wind Instruments in Beethoven's [1]Symphony in C minor: yet, in principle, they are absolutely identical, both owing their origin to a constructive peculiarity which Purcell turned to good account more than a hundred years before the idea suggested itself to Beethoven. And this is not the only remarkable point in the first English 'Te Deum' that was ever enriched with full Orchestral Accompaniments. The alternation of Solo Voices and Chorus is managed with exquisite skill; and sometimes—as at the words 'To Thee Cherubim,' and 'Holy, Holy, Holy,'—produces quite an unexpected, though a perfectly legitimate effect. The Fugal Points, in the more important Choruses, though developed at no great length, are treated with masterly clearness, and a grandeur of conception well worthy of the sublime Poetry to which the Music is wedded. The Instrumentation, too, is admirable, throughout, notwithstanding the limited resources of the Orchestra; the clever management of the Trumpets—the only Wind Instruments employed—producing an endless variety of contrast, which, conspicuous everywhere, reaches its climax in the opening Movement of the 'Jubilate'—an Alto Solo, with Trumpet obbligato—in which the colouring is as strongly marked as in the masterpieces of the 18th century. Judged as a whole, this splendid work may fairly be said to unite all the high qualities indispensable to a Composition of the noblest order. The simplicity of its outline could scarcely be exceeded; yet it is conceived on the grandest possible scale, and elaborated with an earnestness of purpose which proves its Composer to have been not merely a learned Musician, and a man of real genius, but also a profound thinker. And it is precisely to this earnestness of purpose, this careful thought, this profound intention, that Purcell's Music owes its immeasurable superiority to that of the best of his fellow-labourers. We recognise the influence of a great Ideal in everything he touches; in his simplest Melodies, as clearly a in his more highly finished Cantatas; in his Birthday Odes, and Services, no less than in his magnificent Verse Anthems—the finest examples of the later School of English Cathedral Music we possess. The variety of treatment displayed in these charming Compositions is inexhaustible. Whatever may be the sentiment of the words, the Music is always coloured in accordance with it; and always worthy of its subject. It has been said that he errs, sometimes, in attempting too literal an interpretation of his text, as in the Anthem, 'They that go down to the sea in ships,' which begins with a Solo for the Bass Voice, starting upon the D above the Stave, and descending, by degrees, two whole Octaves, to the D below it. No doubt, this passage is open to a certain amount of censure—or would be so, if it were less artistically put together. Direct imitation of Nature, in Music, like Onomatopoiea, in Poetry, is incompatible with the highest aspirations of Art. Still, there is scarcely one of our greatest Composers who has not, at some time or other, been tempted to indulge in it—witness Handel's Plague of Flies, Haydn's imitation of the crowing of the [2]Cock, Beethoven's Cuckoo, Quail, and Nightingale, and Mendelssohn's Donkey. We all condemn these passages, in theory, and not without good reason: yet we always listen to them with pleasure. Why? Because, apart from their materialistic aspect, which cannot be defended, they are good and beautiful Music. A listener unacquainted with the song of the Cuckoo, or the bray of the Donkey, would accept them, as conceived in the most perfect taste imaginable. And we have only to ignore the too persistent realism in Purcell's passage also, in order to listen to it with equal satisfaction; for, it is not only grandly conceived, but admirably fitted, by its breadth of design, and dignity of expression, to serve as the opening of an Anthem which teems with noble thoughts, from beginning to end.[3]

This peculiar feature in Purcell's style naturally leads us to the consideration of another, and a very brilliant attribute of his genius—its intense dramatic power. His Operas were no less in advance of the age than his Anthems, his Odes, or his Cantatas, his keen perception of the proprieties of the Stage no less intuitive than Mozart's. The history of his first Opera, 'Dido and Æneas,' written, in 1675 [App. p.785 "as to the date of Purcell's 'Dido and Æneas,' see Purcell in Appendix"], for the pupils at a private boarding-school in Leicester Fields, is very suggestive. Though he produced this fine work at the early age of 17, it not only shows no sign of youthful indecision, but bears testimony, in a very remarkable manner, to the boldness of his genius. Scorning all compromise, he was not content to produce a Play, with incidental Songs,

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 570b.

- ↑ Quoted under Oboe, vol. ii. p. 488a.

- ↑ The passage was written for the quite exceptional Voice of the Rev. John Gostling, Sub-Dean of S. Paul's. Few Bass singers can do it justice; but many of our readers must remember its admirable interpretation by the late Mr. Adam Leffler.