Number 13

posterior position of the center of gravity of the body in the standing posture; and the correlation of it to certain bony landmarks was easily added, as will be described.

AUTHORS' METHOD OF DETERMINING THE CENTER OF GRAVITY IN THE ERECT POSITION

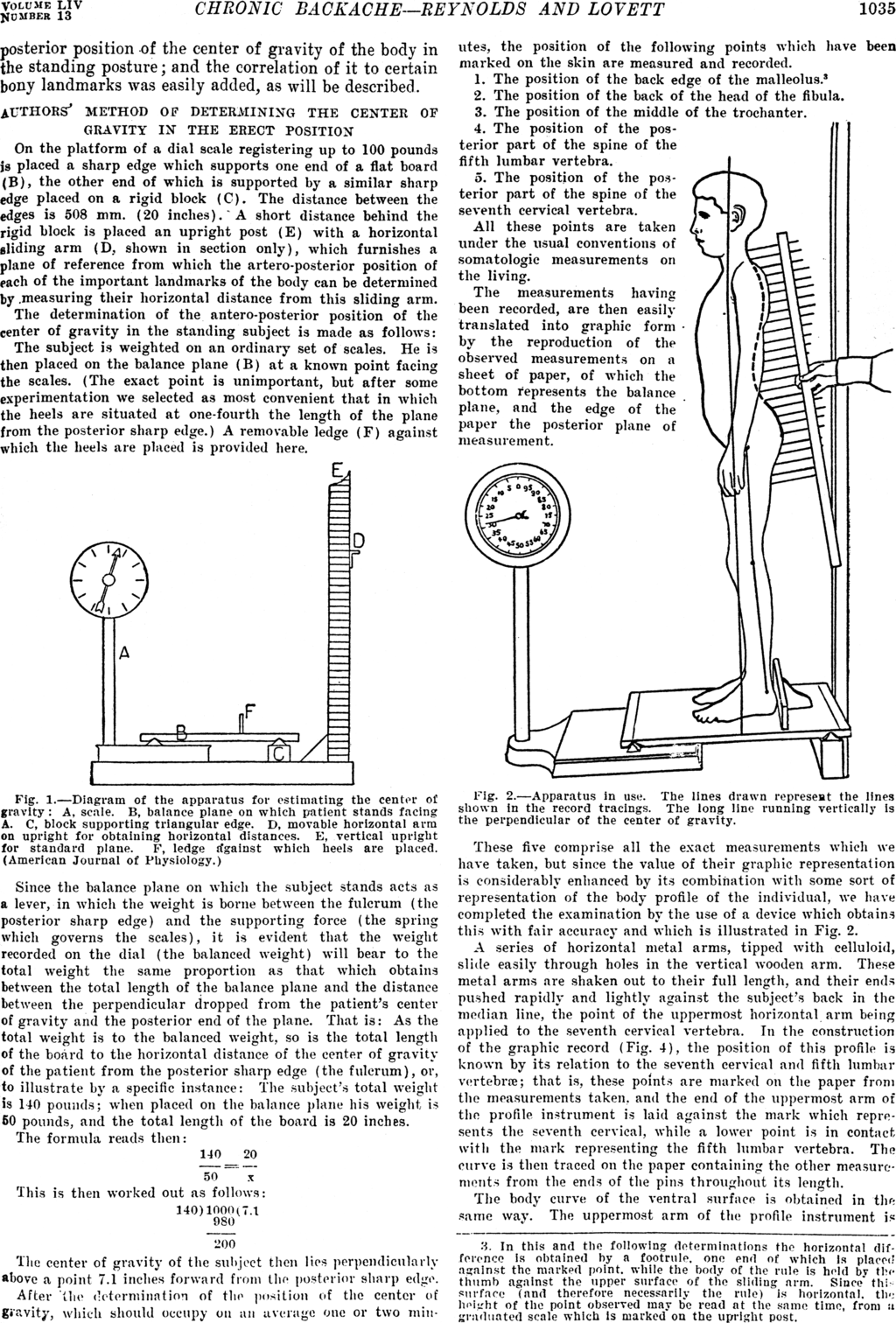

On the platform of a dial scale registering up to 100 pounds is placed a sharp edge which supports one end of a flat board (B), the other end of which is supported by a similar sharp edge placed on a rigid block (C). The distance between the edges is 508 mm. (20 inches). A short distance behind the rigid block is placed an upright post (E) with a horizontal sliding arm (D, shown in section only), which furnishes a plane of reference from which the artero-posterior position of each of the important landmarks of the body can be determined by measuring their horizontal distance from this sliding arm.

The determination of the antero-posterior position of the center of gravity in the standing subject is made as follows:

The subject is weighted on an ordinary set of scales. He is then placed on the balance plane (B) at a known point facing the scales, (the exact point is unimportant, but after some experimentation we selected as most convenient that in which the heels are situated at one-fourth the length of the plane from the posterior sharp edge.) A removable ledge (F) against which the heels are placed is provided here.

Fig. 1.—Diagram of the apparatus for estimating the center of gravity: A, scale. B, balance plane on which patient stands facing A. C, block supporting triangular edge. D, movable horizontal arm on upright for obtaining horizontal distances. E, vertical upright for standard plane. F, ledge against which heels are placed. (American Journal of Physiology.)

Since the balance plane on which the subject stands acts as a lever, in which the weight is borne between the fulcrum (the posterior sharp edge) and the supporting force (the spring which governs the scales), it is evident that the weight recorded on the dial (the balanced weight) will bear to the total weight the same proportion as that which obtains between the total length of the balance plane and the distance between the perpendicular dropped from the patient's center of gravity and the posterior end of the plane. That is: As the total weight is to the balanced weight, so is the total length of the board to the horizontal distance of the center of gravity of the patient from the posterior sharp edge (the fulcrum), or, to illustrate by a specific instance: The subject's total weight is 140 pounds; when placed on the balance plane his weight, is 50 pounds, and the total length of the board is 20 inches.

The formula reads then:

This is then worked out as follows:

The center of gravity of the subject then lies perpendicularly above a point 7.1 inches forward from the posterior sharp edge.

After the determination of the position of the center of gravity, which should occupy on an average one or two minutes, the position of the following points which have been marked on the skin are measured and recorded.

- The position of the back edge of the malleolus.[1]

- The position of the back of the head of the fibula.

- The position of the middle of the trochanter.

- The position of the posterior part of the spine of the fifth lumbar vertebra.

- The position of the posterior part of the spine of the seventh cervical vertebra.

All these points are taken under the usual conventions of somatologic measurements on the living.

The measurements having been recorded, are then easily translated into graphic form by the reproduction of the observed measurements on a sheet of paper, of which the bottom represents the balance plane, and the edge of the paper the posterior plane of measurement.

Fig. 2.—Apparatus In use. The lines drawn represent the lines shown In the record tracings. The long line running vertically is the perpendicular of the center of gravity.

These five comprise all the exact measurements which we have taken, but since the value of their graphic representation is considerably enhanced by its combination with some sort of representation of the body profile of the individual, we have completed the examination by the use of a device which obtains this with fair accuracy and which is illustrated in Fig. 2.

A series of horizontal metal arms, tipped with celluloid, slide easily through holes in the vertical wooden arm. These metal arms are shaken out to their full length, and their ends pushed rapidly and lightly against the subject's back in the median line, the point of the uppermost horizontal arm being applied to the seventh cervical vertebra. In the construction of the graphic record (Fig. 4), the position of this profile is known by its relation to the seventh cervical and fifth lumbar vertebræ; that is, these points, are marked all the paper from the measurements taken, and the end of the uppermost arm of the profile instrument is laid against the mark which represents the seventh cervical, while a lower point is in contact with the mark representing the fifth lumbar vertebra. The curve is then traced on the paper containing the other measurements from the ends of the pins throughout its length.

The body curve of the ventral surface is obtained in the same way. The uppermost arm of the profile instrument is

- ↑ In this and the following determinations the horizontal difference is obtained by a footrule, one end of which is placed against the marked point, while the body of the rule is held by the thumb against the upper surface of the sliding arm. Since this surface (and therefore necessarily the rule) is horizontal. the height of the point observed may be read at the same time, from a graduated scale which is marked on the upright post.