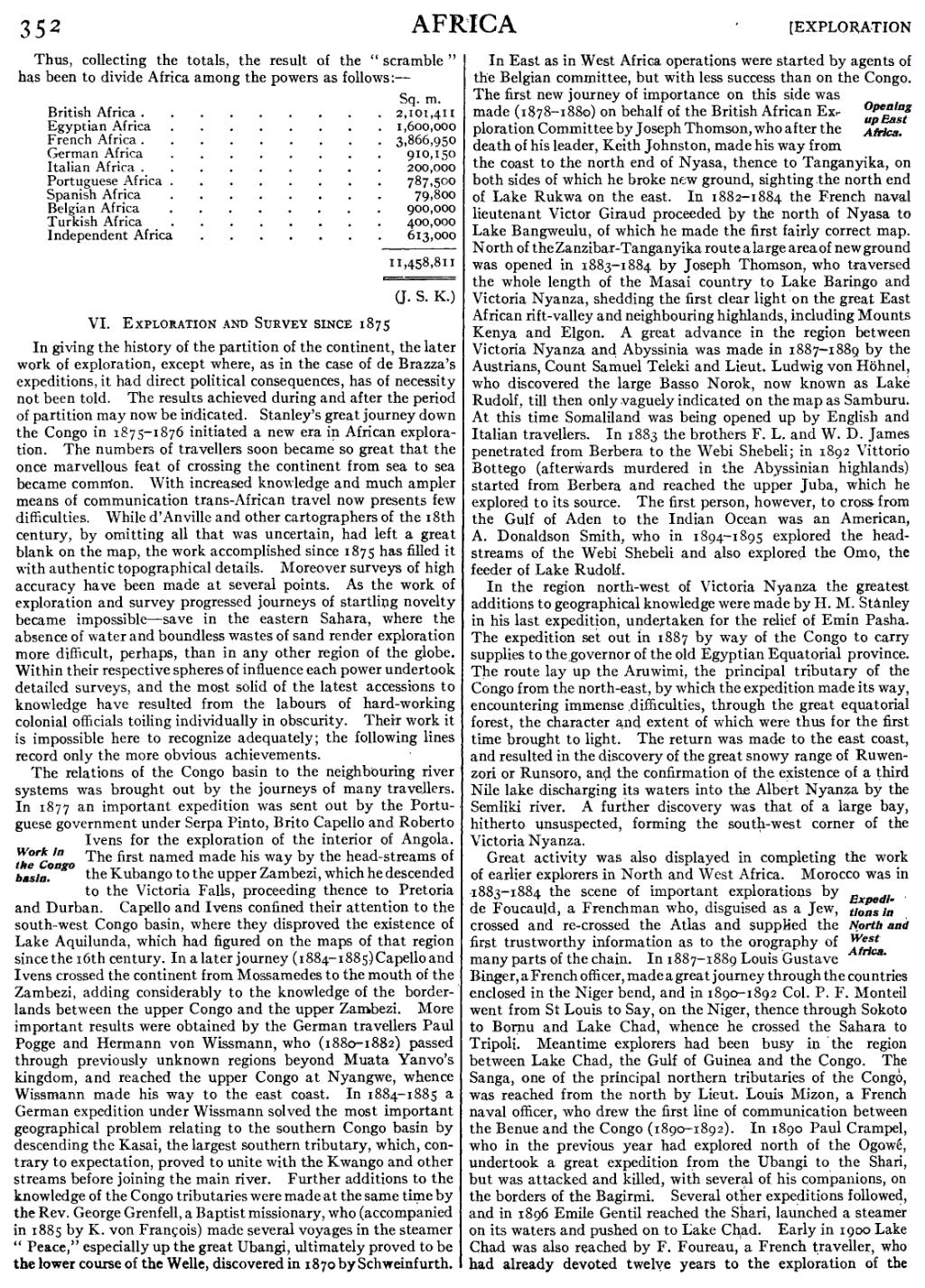

Thus, collecting the totals, the result of the “scramble”

has been to divide Africa among the powers as follows:—

| Sq. m. | ||

| British Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 2,101,411 |

| Egyptian Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 1,600,000 |

| French Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 3,866,950 |

| German Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 910,150 |

| Italian Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 200,000 |

| Portuguese Africa. . . . . . . . . | 787,500 | |

| Spanish Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 79,800 |

| Belgian Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 900,000 |

| Turkish Africa | . . . . . . . . . . . | 400,000 |

| Independent Africa. . . . . . . . | 613,000 | |

| 11,458,811 | ||

(J. S. K.)

VI. Exploration and Survey since 1875

In giving the history of the partition of the continent, the later work of exploration, except where, as in the case of de Brazza’s expeditions, it had direct political consequences, has of necessity not been told. The results achieved during and after the period of partition may now be indicated. Stanley’s great journey down the Congo in 1875–1876 initiated a new era in African exploration. The numbers of travellers soon became so great that the once marvellous feat of crossing the continent from sea to sea became common. With increased knowledge and much ampler means of communication trans-African travel now presents few difficulties. While d’Anville and other cartographers of the 18th century, by omitting all that was uncertain, had left a great blank on the map, the work accomplished since 1875 has filled it with authentic topographical details. Moreover surveys of high accuracy have been made at several points. As the work of exploration and survey progressed journeys of startling novelty became impossible–save in the eastern Sahara, where the absence of water and boundless wastes of sand render exploration more difficult, perhaps, than in any other region of the globe. Within their respective spheres of influence each power undertook detailed surveys, and the most solid of the latest accessions to knowledge have resulted from the labours of hard-working colonial officials toiling individually in obscurity. Their work it is impossible here to recognize adequately; the following lines record only the more obvious achievements.

The relations of the Congo basin to the neighbouring river systems was brought out by the journeys of many travellers. In 1877 an important expedition was sent out by the Portuguese government under Serpa Pinto, Brito Capello and Roberto Ivens for the exploration of the interior of Angola. The first named made his way by the head-streams ofWork in the Congo basin. the Kubango to the upper Zambezi, which he descended to the Victoria Falls, proceeding thence to Pretoria and Durban. Capello and Ivens confined their attention to the south-west Congo basin, where they disproved the existence of Lake Aquilunda, which had figured on the maps of that region since the 16th century. In a later journey (1884–1885) Capello and Ivens crossed the continent from Mossamedes to the mouth of the Zambezi, adding considerably to the knowledge of the borderlands between the upper Congo and the upper Zambezi. More important results were obtained by the German travellers Paul Pogge and Hermann von Wissmann, who (1880–1882) passed through previously unknown regions beyond Muata Yanvo’s kingdom, and reached the upper Congo at Nyangwe, whence Wissmann made his way to the east coast. In 1884–1885 a German expedition under Wissmann solved the most important geographical problem relating to the southern Congo basin by descending the Kasai, the largest southern tributary, which, contrary to expectation, proved to unite with the Kwango and other streams before joining the main river. Further additions to the knowledge of the Congo tributaries were made at the same time by the Rev. George Grenfell, a Baptist missionary, who (accompanied in 1885 by K. von François) made several voyages in the steamer “Peace,” especially up the great Ubangi, ultimately proved to be the lower course of the Welle, discovered in 1870 by Schweinfurth.

In East as in West Africa operations were started by agents of the Belgian committee, but with less success than on the Congo. The first new journey of importance on this side was made (1878–1880) on behalf of the British African Exploration Committee by Joseph Thomson, who after the death of his leader, Keith Johnston, made his way fromOpening up East Africa. the coast to the north end of Nyasa, thence to Tanganyika, on both sides of which he broke new ground, sighting the north end of Lake Rukwa on the east. In 1882–1884 the French naval lieutenant Victor Giraud proceeded by the north of Nyasa to Lake Bangweulu, of which he made the first fairly correct map. North of the Zanzibar-Tanganyika route a large area of new ground was opened in 1883–1884 by Joseph Thomson, who traversed the whole length of the Masai country to Lake Baringo and Victoria Nyanza, shedding the first clear light on the great East African rift-valley and neighbouring highlands, including Mounts Kenya and Elgon. A great advance in the region between Victoria Nyanza and Abyssinia was made in 1887–1889 by the Austrians, Count Samuel Teleki and Lieut. Ludwig von Höhnel, who discovered the large Basso Norok, now known as Lake Rudolf, till then only vaguely indicated on the map as Samburu. At this time Somaliland was being opened up by English and Italian travellers. In 1883 the brothers F. L. and W. D. James penetrated from Berbera to the Webi Shebeli; in 1892 Vittorio Bottego (afterwards murdered in the Abyssinian highlands) started from Berbera and reached the upper Juba, which he explored to its source. The first person, however, to cross from the Gulf of Aden to the Indian Ocean was an American, A. Donaldson Smith, who in 1894–1895 explored the head-streams of the Webi Shebeli and also explored the Omo, the feeder of Lake Rudolf.

In the region north-west of Victoria Nyanza the greatest additions to geographical knowledge were made by H. M. Stanley in his last expedition, undertaken for the relief of Emin Pasha. The expedition set out in 1887 by way of the Congo to carry supplies to the governor of the old Egyptian Equatorial province. The route lay up the Aruwimi, the principal tributary of the Congo from the north-east, by which the expedition made its way, encountering immense difficulties, through the great equatorial forest, the character and extent of which were thus for the first time brought to light. The return was made to the east coast, and resulted in the discovery of the great snowy range of Ruwenzori or Runsoro, and the confirmation of the existence of a third Nile lake discharging its waters into the Albert Nyanza by the Semliki river. A further discovery was that of a large bay, hitherto unsuspected, forming the south-west corner of the Victoria Nyanza.

Great activity was also displayed in completing the work of earlier explorers in North and West Africa. Morocco was in 1883–1884 the scene of important explorations by de Foucauld, a Frenchman who, disguised as a Jew, crossed and re-crossed the Atlas and supplied the first trustworthy information as to the orography ofExpeditions in North and West Africa. many parts of the chain. In 1887–1889 Louis Gustave Binger, a French officer, made a great journey through the countries enclosed in the Niger bend, and in 1890–1892 Col. P. F. Monteil went from St Louis to Say, on the Niger, thence through Sokoto to Bornu and Lake Chad, whence he crossed the Sahara to Tripoli. Meantime explorers had been busy in the region between Lake Chad, the Gulf of Guinea and the Congo. The Sanga, one of the principal northern tributaries of the Congo, was reached from the north by Lieut. Louis Mizon, a French naval officer, who drew the first line of communication between the Benue and the Congo (1890–1892). In 1890 Paul Crampel, who in the previous year had explored north of the Ogowé, undertook a great expedition from the Ubangi to the Shari, but was attacked and killed, with several of his companions, on the borders of the Bagirmi. Several other expeditions followed, and in 1806 Emile Gentil reached the Shari, launched a steamer on its waters and pushed on to Lake Chad. Early in 1900 Lake Chad was also reached by F. Foureau, a French traveller, who had already devoted twelve years to the exploration of the