age—are broken and trampled. The only comment obtained in return for all the remonstrance of the united gentry, is that “boys will be boys,—especially at Christmas.”

When New Year’s Eve draws on, these and all other vexations are dismissed, as unworthy to interfere with that repose of mind in which each genuine marked period of the individual human life should close. In one sense, it does not seem real to begin a new year in the very midst of the dead season in which the preceding closes; and I, for one, feel the spring to be, in regard to the face of Nature, the opening of the year. But there are reasons which justify the common consent in the existing arrangement by which our year ends with December; and in the lapse of a complete year there is a sound reality, widely different from the conventional anniversaries which celebrate anything else. New Year’s Eve is then a night of deep and genuine interest. There is no effort in the gentle emotion with which we listen to the chimes, when we have unbarred the shutters and opened the window. If the night is still, and the stars are clear, it is with them for witnesses that we exchange the family kiss all round, and wish one another a Happy New Year.

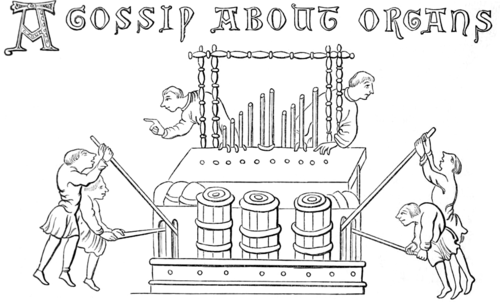

Hand Organ, from the Nuremberg Chronicle.We wonder how many, out of the thousands to whom the tones of the organ are so familiar, ever give more than a passing thought to it, or reflect on the science and skill that have been lavished on it, from the time of the reed-pipes of the ancients up till now, when it has become the most gigantic and complex musical instrument of modern times. Indeed, many amateurs, fond as they are of music, and of church-music in particular, are surprised when they first begin to find out what a vast amount of machinery is packed into such a small compass, and what a number of abstruse and scientific principles have to be attended to before they can extract even one sweet sound. The earliest organ was probably nothing more than a series of reeds blown by the mouth, a proceeding which was found so tiresome, that it was not long before the bellows came into use, so as to ensure a constant supply of wind; but even then it was only a rudiment of the present instrument, since it was not till the eleventh century that a keyboard was first added to the one in Magdeburgh Cathedral. Here was an epoch in the history of sacred music—the lowest step of that platform of divine harmony which has since risen in such noble strains, and which is still ever ascending. What masters in the art have played out their lives since then, filling the world with the glorious creations of their genius!