The New Forest: its history and its scenery/Chapter 7

CHAPTER VII.

THE SOUTH-WESTERN PART—BROCKENHURST, BOLDRE, SWAY, HINCHELSEA, AND BURLEY.

At present we have seen nothing of the actual Forest. It is only as we go northward that we begin to enter its woods. Instead of the old Forest track, a road now runs from Beaulieu to Brockenhurst, along which we will go. So, leaving the village, and passing a few straggling half-timbered cottages, we reach Stickland's Hill, where, down in the valley, we can see the Exe winding round the old Abbot's House set amongst its green elms. Farther on we come to Hatchet Gate, and the Forest then spreads before us, with Hatchet Pond on our left, and Little Wood and the Moon Hill Woods on our right; whilst, here and there on the common, rise scattered barrows.

And now, instead of keeping to the road, let the reader make right across the plain, by one of the Forest tracks, to the woods at Iron's Hill. The stories, with which most books on the Forest abound, of persons being swamped in morasses, are much exaggerated. Mind only this simple rule—wherever you see the white cotton-grass growing, and the bog-moss particularly fine and green, to avoid that place.

And now, when you are fairly out on the moor, you will feel the fresh salt breeze blowing up from the Solent, and see the long treeless line of the Island hills in strange contrast with the masses of wood in front; whilst the moor itself, if it be August, waves with purple and crimson, except where, here and there, rise great beds of fern—green islands, in the red sea of heath.

Most of the finest timber at Iron's Hill and Palmer's Water has been lately cut. Keeping on, however, we shall again come out upon the road which leads down to the stream, close to a mill. Passing over the footbridge, we skirt Brockenhurst Manor, where, at Watcombe, once lived Howard the philanthropist, and so at last reach the village.

So greatly has the Forest been reduced in size, that Brockenhurst, once nearly its centre, is now only a border village. Its Old-English name (the badger's wood), like that of Everton the wild-boar place, on the southern side of the Forest, tells its own story. It consists of one long straggling street, and a few scattered houses, with one or two village inns. Much of its wildness has been spoilt by the railroad; and in consequence, too, of the adjoining manor of Brockenhurst, it appears even less than it really is in the Forest. Still, however, if the reader wishes to see the Forest woods and heaths towards the south, let him come here, and the village accommodation will only give an additional charm to the scenery. I, for my part, do not know that a clean English village inn, with its sanded floor, and its best parlour kept for state occasions, makes such bad quarters. It is a real pleasure to find some spots on the earth not yet disfigured by fashionable hotels.

At Brockenhurst existed one of those tenures of knight-service once so common throughout England. Here Peter Spelman, an ancestor of the antiquary, held a carucate of land by the service of finding for Edward II. an esquire clad in coat of mail for forty days in the year, and whenever the King came to the village to hunt, litter for his bed, and hay for his horse, which last clause will give us some insight into the often rough living and habits of the fourteenth century.[1] Here, too, not many years ago, droves of deer would at night, when all was still, race up the village street, and the village dogs leap out and kill them, or chase them back to the Forest.

The church, one of the only two in the Forest mentioned in Domesday,[2] is built on an artificial mound on the top of a hill, a little way out of the village, so that it might serve as a landmark in the Forest.[3] The church has been sadly mutilated. A wretched brick tower has been patched on at the west end; and on the north side a new staring red brick aisle, which surpasses even the usual standard of ugliness of a dissenting chapel. On the south side stands the Norman doorway, with plain escalloped capitals, and an outside arch ornamented with the indented and chevron mouldings. The chancel is Early-English, whilst the plain chancel arch which springs without even an impost from the wall, is very early Norman. Under one of the chancel windows rises the arch of an Easter sepulchre, whilst a square Norman font, of black Purbeck marble, stands at the south-west end of the nave.

If the church, however, has been disfigured, the approach to it fortunately remains in all its beauty. For a piece of quiet English scenery nothing can exceed this, A deep lane, its banks a garden of ferns, its hedge matted with honeysuckle, and woven together with bryony, runs, winding along a side space of green, to the latch-gate, guarded by an enormous oak, its limbs now fast decaying, its rough bark grey with the perpetual snow of lichens, and here and there burnished with soft streaks of russet-coloured moss; whilst behind it, in the churchyard, spreads the gloom of a yew, which, from the Conqueror's day, to this hour, has darkened the graves of generations.[4]

But the charm of Brockenhurst, as of all the Forest villages, consists in the Forest itself. To the north runs the small Forest stream, blossomed over in the summer with water-lilies. On the left lies Black Knoll, with its waste of heath and gorse, running up to the young plantations of New Park. On the right, Balmor Lawn, with its short, sweet turf, where herds of cattle are pasturing, stretches away to Holland's Wood, with old thorns scattered here and there, in the spring lighting up the Forest with their white may.

Just now though, it is the southern part of the Forest we must see. So going back again for a little way upon the Beaulieu Road, and leaving it just above the foot-bridge for Whitley Lodge, let the reader go on to Lady Cross. Suddenly he will come out upon the northern edge of Beaulieu Heath, and see again the Island Hills. To the people in the Forest, the Island is their weather-glass. If its hills look dark blue and purple, then the weather will be fine; but if they can see the houses and the chalk quarries on the hill sides, the rain is sure to come.

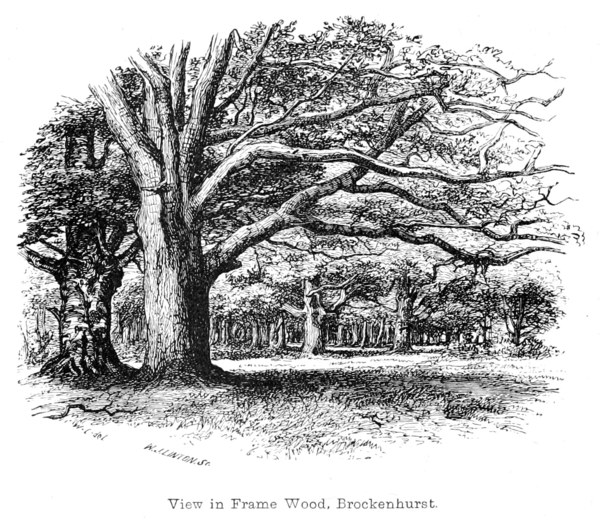

Keeping straight on, with Lady Cross Lodge to our left, we enter Frame Wood, with its turf and its bridle roads winding under the Forest boughs. Down in the bottom runs the railroad bending away to the north. On the other side, the thick woods of Denny rise; and the clump of solitary beeches on the top of the knoll shows the last remains of Wood Fidley, so well known as having given rise to the Forest proverb of "Wood Fidley rain," that is, rain which lasts all the day.

Here you can wander on for miles, as far as the manor of Bishop's Ditch, belonging to Winchester College, which the Forest peasant will tell you was a grant of land as much as the Bishop of Winchester could in a day crawl round on his hands and knees. As to losing yourself, never mind. The real plan to enjoy the Forest is to wander on, careless whether you lose yourself or not. In fact, I believe the real method is to try and lose yourself, finding your greatest pleasure in the unexpected scenes of beauty into which you are led.

There are plenty of other Forest rambles round Brockenhurst which must not be forgotten. Just at the western edge of Beaulieu Heath, about three miles off, stands Boldre Church, with its solitary churchyard surrounded by trees. On one side, it looks out upon the bare Forest; and on the other, down into the cultivated valley. Most suggestful, most peaceful is this twofold prospect, telling us alike both of work and companionship, as, too, of solitude—all of them, in religion, so needful for man. Its tower stands boldly out, almost away from the church, just between the nave and the chancel, serving formerly, like Brockenhurst steeple, as a landmark to the Forest; whilst the long outline of the nave is broken only by the south porch, and its three dormer windows. Close to the north side, under the shadow of a maple, lies one of the truest lovers of Nature—Gilpin, the author of the Scenery of the New Forest, with a quaint, simple inscription on his gravestone written by himself. In the church are tablets both to him and Bromfield, the botanist, a man like him in many ways, but who, dying abroad, was not allowed to rest beside him in this quiet graveyard.

Here, too, Southey married his second wife, Caroline Bowles. The south aisle is the oldest part, with its three Norman arches rising from square piers, whilst the north aisle is divided from the nave by a row of Early-English arches springing from plain black Purbeck marble shafts. In the east window of this aisle were once painted the arms of the Dauphin of France—the fleurs de lis—blazoned, as they were formerly, over the whole field, telling us the story of Lewis having been invited to England and crowned king by John's barons, and whose traditional flight at Leap has been mentioned.

Down below, in the valley of the Brockenhurst Water, lies Boldre, the Bovre of Domesday, with its meadows and cornfields. It is worth while to pause for a moment, and notice the corruption of Boldre into Bovre by the Norman clerks. The word is from the Keltic, and signifies the full stream ("y Byldwr"), and has nothing to do with oxen. We must, too, bear in mind that the various Oxenfords and Oxfords are themselves corruptions, and really come not from oxen at all, but Usk, literally meaning the stream-ford or stream-road, and are in no way connected with the various Old-English Rodfords to be found in different parts of the kingdom. This corruption of language we see daily going on in our own Colonies, but it is well to pause and remember that the same process has taken place in our own country.

Passing over the bridge, and up the village, and under the railway arch, we once more reach the Forest at Shirley Holms, coming out on Shirley and Sway Commons. Here again, as on Beaulieu Heath, there is not a single tree, nothing but one vast stretch of heather, which late in the summer covers the ground with its crimson and amethyst. There is only one fault to be found with it, that when its glory is past it leaves so great a blank behind: its grey withered flowers and its grey scanty foliage forming such a contrast with its previous brightness and cheerfulness.

But these two commons will at all times be interesting to the archaeologist and historian. On the north-east side lies the Roydon, that is, the rough ground, a word which we find in other parts of the Forest; and not far from it is Lichmore or Latchmore Pond—the place of corpses—which is confirmed by the various adjoining barrows.[5]

After this point, there is nothing to attract the traveller, unless he is a botanist, to the south. Wootton, and Wilverley, and Setthorns, and Holmsley, are all young plantations, whilst at Wootton the Forest now entirely ceases, though once stretching five miles farther, as far as the sea. So let him make his way to Longslade, or Hinchelsea Bottom, as it is indifferently called, where about the middle of June blossoms the lesser bladderwort (Utricularia minor), and about the same time, or rather later, the floating bur-reed (Sparganeum natans).

Above, rises Hinchelsea Knoll, with its old hollies and beeches; and still farther to the north the high lands round Lyndhurst and Stony Cross crowned with woods. Westward, the heather stretches over plain and hill till it reaches Burley, Making right through Hinchelsea, and then skirting the north side of Wilverley plantations, we shall come to the valley of Holmsley, so beloved by Scott, and which put him in mind of his native moors, without seeing which once a year, he so pathetically said, he felt as if he should die. Its wild beauty, however, is in a great measure spoilt by the railroad, and the large trees which grew in Scott's time have all been felled.

Burley itself, which now lies just before us, is one of the most primitive of Forest hamlets, the village suddenly losing itself amongst the holms and hollies, and then reforming itself again in some open space. So thoroughly a Forest village, it is proverbially said to be dependent upon the yearly crop of acorns and mast, or "akermast," as they are collectively called. To the south-west stands Burley Beacon, where some entrenchments are still visible, and the fields lying round it are still called "Greater" and "Lesser Castle Fields," and "Barrows," and "Coffins," showing that the whole district has once been one vast battle-field.

Close to the village are the Burley quarries, where the so-called Burley rock, a mere conglomerate of gravel, the "ferrels," or "verrels," of North Hampshire, is dug, formerly used for the foundations of the old Forest churches, as at Brockenhurst, and Minestead, and Sopley in the Vale of the Avon. The great woods round Burley have all been cut, except a few beech-woods, but here and there "merry orchards" mingle themselves with the holms and hollies, wandering, half-wild, amongst the Forest.[6]

Turning away from the village, and going north-east, before us rise great woods—Old Burley, with its yews and oaks, where the raven used to build; Vinney Ridge, with its heronry at one extremity, and the Eagle Tree at the other; whilst behind us are the young Burley plantations. Here, near the Lodge, scattered in some fields, stand the remains of the "Twelve Apostles," once enormous oaks, reduced both in number and size, with

And high tops bald with dry antiquity."

And now, if the reader does not mind the swamps—and if he really wishes to know the Forest, and to see its best scenes, it is useless to mind them—let him make his way across to Mark Ash, the finest beechwood in the Forest, which even on a summer's day is dark at noon. Thence the wood-cutter's track will take him by Barrow's Moor and Knyghtwood, where grows the well-known oak. Here a different scene opens out with broad spaces of heath and fern, where the gladiolus shows its red blossoms among the green leaves of the brake; whilst on the hill, distinguished by its poplars, stands Rhinefield, with its nursery, and, below, the two woods of Birchen Hat, where the common buzzard yearly breeds.

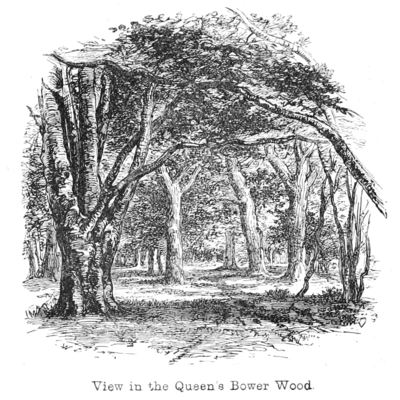

Keeping along the main road, which is just before us, nearly as far as the New Forest Gate, we will turn in at Liney Hill Wood, going through the woods of Brinken, and the Queen's Mead, and the Queen's Bower, following the course of the stream.

Very beautiful is this walk, with its paths which stray down to the water's edge, where the cattle come to drink; the stream pausing round some oak roots, which pleach the banks, lingering in the darkness of the shade, and at last going away with reluctance.

Few things, of their sort, can equal these lowland Forest streams, the water tinged with the iron of the district, flashing into amber in the sunlight, and deepening into rich browns in the shade, making the pebbles hazel as it ripples over them.

All the way along grow oaks and beeches, each guarded with its green fence of kneeholm, and furred with moss, which the setting sun paints with bands of light. And so, in turn, passing Burley and Rhinefield Fords, and Cammel Green, and the Buckpen, where the deer used to be fed in winter, the path suddenly comes out by a lonely grass-field, known as the Queen's Mead, and immediately after enters the Queen's Bower Wood. At the farther end, a bridge crosses the brook by the side of one of the many Boldrefords in the Forest; and in the distance, across Black Knoll, shine the white houses of Brockenhurst.

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ Blount's Fragmenta Antiquilatis. Ed. Beckwith, p. 80, 1815. Testa de Nevill, p. 235 a (118). We know, however, that our forefathers, long before this, possessed beds, or rather cots, hung round with rich embroidered canopies. For their general love, too, of comfort and personal ornament and dress, we need go no further than to Chaucer's description of "Richesse," in his Romaunt of the Rose. Englishmen, however, were still then, as now, ever ready to lead a rough life if necessary, and to make their toil their pleasure.

- ↑ In that portion of it which comes under the title of "In Foresta et circa eam." See chap. iii. p. 31.

- ↑ All over England did the church towers serve as landmarks, alike in the fen and forest districts. Lincolnshire and Yorkshire can show plenty of such steeples. At St. Michael's at York, to this hour, I believe, at six every morning, is rung the bell whose sound used to guide the traveller through the great forest of Galtres; whilst at All Saints, in the Pavement, in the same city, is shown the lantern, which every night used to serve as a beacon.

- ↑ The following measurements may have some interest, and can be compared with those of the oaks and beeches in the Forest, given in chap. ii. p. 16, foot-note:—Circumference of the oak, twenty-two feet eight inches. Yew, seventeen feet. An enormous yew, completely hollow, however, stands in Breamore churchyard, measuring twenty-three feet four inches. There are certainly no yews in the Forest so large as these; and their evidence would further show that at all events the Conqueror did not destroy the churchyards. As here, too, there remains some Norman work in the doorway of Breamore church.

- ↑ For some account of these barrows, see chapter xvii.

- ↑ The word is from the French merise. At Wood Green, in the northern part of the Forest, a "merry fair" of these half-wild cherries is held once a week during the season, probably similar to that of which Gower sung.