The Republic of Plato

THE REPUBLIC

PLATO

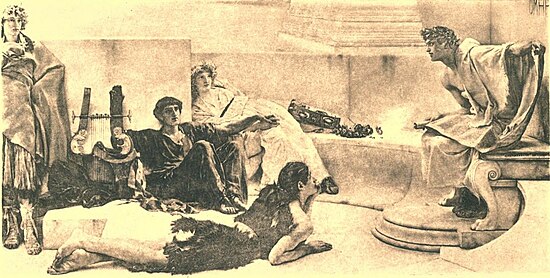

A READING FROM HOMER.

Photogravure from the original painting by Laurence Alma-Tadema.

THE REPUBLIC OF PLATO

AN IDEAL COMMONWEALTH

TRANSLATED BY

BENJAMIN JOWETT, M. A.

LATE REGIUS PROFESSOR OF GREEK

IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

WITH A SPECIAL INTRODUCTION BY

WILLIAM CRANSTON LAWTON

PROFESSOR OF GREEK LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

IN ADELPHI COLLEGE, BROOKLYN, N. Y.

REVISED EDITION

Copyright, 1901,

By THE COLONIAL PRESS.

SPECIAL INTRODUCTION

Among classical authors Plato is second in importance to Homer only, if even to him. To call the founder of the Academy the chief of philosophers ancient or modern is a very inadequate statement, and even, in one important respect, misleading. Though at war with many of the strongest moral tendencies of his race and time, he was none the less himself a Greek, an Athenian, to the core. That is, he was an artist, with eyes opened wide for all beauty in color, form, and motion. The Athenians saw, as perhaps no folk of later days have seen, the glorious charm of the universe, of life, of man. The varied pageant of earthly existence did not pall upon them. Only after a century or two of provincial enslavement is Menander’s cry heard:

“That man I count most happy, Parmeno,

Who, after he hath viewed the splendors here,

Departeth quickly thither whence he came.”

To be sure, there is a vein of occasional repining in the Hellenic poets, as, indeed, in all thoughtful men, just sufficient to show that they saw, also, the pathos of life. In the Platonic “Apology” Socrates declares that death, even if it be only a dreamless sleep, is still a gain, since there are few days or nights in a long life which a wise man can recall that were so happy as the night when he slumbered most unconscious. But it is from the lips of the Homeric Achilles, bereft and conscious of imminent doom, from the octogenarian poet of an Œdipus himself world-worn, or from a Socrates already upon the threshold of old age, strenuous to reconcile himself and his to the inevitable, that such utterances fall.

To Pindar and the countless lesser lyric poets, to the Tragic Three and their forgotten rivals, as to Homer, life, and especially youth and early manhood, seemed far more fair than any “casual hope of being elsewhere blest.” The gods and heroes, the kindly lesser powers that haunt mountain, wood, and stream, were almost as near to the fifth-century Hellenes as to the mythic age itself. Ordinary men knew all the Homeric poems by heart. In popular tradition, in the myriad forms of painting and sculpture, above all as vivified afresh by the genius of dramatic poetry, the legends

“Of Thebes or Pelops’ line,

Or the tale of Troy divine,”

still hung like a splendid tapestry about the calmer reality.

That reality itself was anything but commonplace. The glorious war against the Persian invader left the most deep-rooted confidence that the Hellene had no rival, and that Athens was the natural capital and university of Hellas. Pericles lived and died in that belief: and Plato’s life all but overlapped that of the idealistic statesman. He must have actually looked on, an eager-eyed boy, when the armada sailed forth upon the Sicilian expedition, amid yet wilder dreams of occidental empire.

The failure and disillusion came—swift and bitter, indeed. Yet victorious Sparta did not destroy, or even utterly and permanently humble, her nobler rival. Throughout Plato’s mature life Athens was again self-governed; she had regained a fleet, some commerce, and even a modest leadership in a maritime league, though never her pristine haughtiness and far-reaching hopes. Her people looked backward, rather than forward, with fond pride. Their instinct was right. Macedon, not Attica, was to lead Hellenism to world-wide dominion, though the culture, the art, and the speech of the race were to remain always essentially Attic.

Throughout the fourth century B.C., indeed, supremacy in things spiritual still abode with Athens. With Plato walked and talked, under the over-arching trees of Academe, the choicest spirits of Hellas—greatest of all, Aristotle, “master of them that know”—though less happy than Plato and all they that are dreamers with him of the dream divine. Aristotle was drawn to Athens by the great teacher, and spent there his happiest and most useful years.

Plato, then, was no mere introverted musing psychologist of the closet. Indeed, he is our chief source of knowledge for the conversational speech of fourth-century Athens. The streets, the gymnasia, the beauty of youth, the pride of manhood, and the teeming life of the city generally, are revived in his dialogues as nowhere else. The picturesque setting, the sharply outlined characters, the realistic grace and variety in speech, and the easily unfolding plots of his most perfect dialogues, such as the Protagoras and Symposium, show that he might have been—that, indeed, he actually is, along with the other sides of his composite manifold lifework—as masterly a dramatist as Sophocles. Even as a fun-maker, he is but second, though indeed a far-away second, to his contemporary, the unapproachable mad spirit that in the name of conservatism and the “good old ways” turned all the decencies and realities of life upside down in his comedy. Aristophanes himself, it should be remembered, is a welcome guest at the Platonic Banquet. He speaks there, even on the topic of Love, wittily and with bold creative fancy, though Socrates’ eloquence makes all that went before seem idle chatter. He drinks well and manfully, too, though here again he meets his match. The Symposium ends with a glimpse of Socrates, sober still and argumentative to the end, sitting, as the long night wanes, between Aristophanes and their host, the tragic poet Agathon. While they quaff in turn from the great bowl, the philosopher is convincing the reluctant and drowsy pair that the consummate dramatist will fuse comedy and tragedy, or become alike supreme in both. We need not call this a prophecy of Shakespeare’s advent. It was already largely made true in Plato’s own noble art, which saw life whole, alike an amusing and a pathetic spectacle.

We must insist, then, that Plato’s was a great, all but the greatest, dramatic genius. The characteristics of that most noble of arts, including even the effacement of the artist’s own person, are seen at once from the fact, that all his works are—not didactic sermons, in form at least, but—realistic dialogues: and the chief interlocutor in most, a prominent figure in nearly all, is that most grotesque and most pathetic, most ugly and most fascinating of figures, whether in fiction or in real life, “short of stature, stout of limb,” satyr-faced and siren-voiced, Socrates the Athenian.

The question, how much in these wonderful dialogues is Socratic and how much Platonic, can never be fully answered. From the sober, pious, prosaic-minded Xenophon we have a sketch of Socrates’ life, and a report of numerous conversations. The sketch is apparently truthful, and evidently most inadequate. Neither the love nor the hate inspired by that unique life can be sufficiently explained from the Xenophontic “Memorabilia.” Plato’s “Apology,” though a masterpiece of self-concealing art, contains nothing which Socrates could not or may not have said before his judges: and we have every reason to believe that Plato was actually present during the trial. On the other hand, the equally famous and vivid “Phædo” describes the sage’s last day, surrounded in the prison by his faithful disciples, and assuring them of the soul’s immortality: but in this case Plato’s own absence through illness is noted in the text itself. The argument in the “Phædo” shows wide philosophic thought and study, and includes largely doctrines which are generally believed to be Plato’s own. But at any rate such a dialogue as the “Timæus” can contain little that is truly Socratic. The master himself utterly condemned the childish guesses of his age at astronomical truths and physical science generally, and constantly advised whole-hearted devotion to the practical problems of man’s soul and moral nature. Yet in the “Timæus,” as in the grand myth which closes the “Republic,” there is an elaborate hypothesis as to the form and significance of the universe, with an attempt to explain from it the whole nature and destiny of man.

The general fact, then, is clear, that Plato, surviving his master some fifty years, lived his own life of unresting mental activity and wondrous growth, yet always retained in writing the conversational form of his own personal teaching: and, almost to the end, retained also that most picturesque central figure in all discussions: thus proclaiming his obligation, for all he had acquired, to the original inspiration of Socrates. So Dante’s Beatrice, a chief saint in heaven, has the features, the name, even the nature, of the child and maid so well beloved at nine and at twenty. Such loyalty does not lessen the claim of either poet or philosopher to originality and to direct inspiration from the highest sources.

Plato is always a student and teacher of ethical psychology. The “Republic” is an investigation as to the exact nature and definition of justice. The avowed purpose in outlining the ideal State is to descry, writ large therein, the quality which we cannot clearly see in the microcosm, man. To take for granted the essential identity between the individual life and the career of a State is an example of Plato’s splendid poetic audacity. Socrates’ favorite pupil, here fully in accord with the real Socrates, firmly believed that accurate knowledge in such matters was the only secure road to character: that knowledge, reasoned knowledge, is essentially one with virtue, and that ignorance is the true source of folly, of sin, of misery. Aristotle assures us that the real Socrates discovered inductive reasoning and showed the value of general definitions; both weighty contributions to true philosophy. Yet we may be sure that in the “Republic,” the masterpiece of Plato’s later maturity, the chief contribution is from the author’s own creative imagination.

In many of the dialogues we are taught that man’s soul is triple in its nature. The most magnificent illustration of this doctrine is the myth of the “Phædrus,” where the baser appetite and the nobler passionate impulse appear as a pair of steeds, one usually bent on thwarting, the other on aiding, the charioteer, who is, of course, the Will. In the “Republic” this triple division reappears, the workers and the soldiers of the State being alike under the guidance of the counsellors.

Again, Plato firmly believes that our life is a banishment of the soul from an infinitely higher and happier existence, and that each may hope to rise again, when worthy, to the sphere from which he has fallen through sin. Naturally blended with this creed is the belief in reincarnation, in metempsychosis; a faith not peculiar to any land or age. So the Hindu to-day hopes to escape at last, after many lives lived out with innocence, from the merciless “wheel of things.” Some memory, even, of the higher sphere, the soul may still retain. Here Wordsworth’s loftiest ode will help to explain the faith of Plato.

Most famous perhaps of all Plato’s beliefs is the doctrine of the Ideas. No quality, no attribute, no material form, even, exists in our world of sense in its perfection. Out of many manifestations of, for instance, courage or generosity, of man or beast, or even of actual chairs or tables, we come nearer to some typical conception, or, as Plato poetically puts it, we recall imperfectly to mind that ideal type which the soul actually beheld in its higher estate. Even in its crudest and half-grotesque statements this belief is evidently an approach, as is so often the case with Plato’s sublimest guesses, to the methods of modern science.

These peculiar doctrines of Plato, more fully defended in other dialogues, are here largely taken for granted from time to time as the argument requires. In general, the philosopher is at war with the spirit of the age. Perhaps this has been and must be always true, until, as Socrates says, “the kings of earth become sages, or the sages are made our kings.” Then, as now, the average man sought wealth, luxury, power, fame, by means more or less selfish and unscrupulous. Now, as then, the art most studied is the art of “getting on in the world.” The Sophists, against whom so many a Socratic or Platonic arrow of satire is sped, taught very much what, mutatis mutandis, business colleges, schools of commerce, etc., undertake to-day. For such fluency in rhetoric and oratory, or such general information, as would help to ready success in business or politics, there was a good demand, at generous prices; and the “Sophists” have continued to pocket their fees, though the barefoot Socrates and the wealthy aristocrat Plato never wearied of gibing at them for it.

The features of Plato’s commonwealth most repugnant to Greek or Yankee, community of goods, dissolution of the family, etc., were expressly intended to force upon a reluctant folk a somewhat ascetic ideal of simple living, with abundant leisure for high, philosophic thought. It was a scholar’s paradise; and the late Thomas Davidson doubtless re-established in his summer home many of the conditions under which Plato actually dwelt with his disciples of the suburban Academy. The monastery, and its offspring the mediæval university, have close kinship with the dream as with the reality of Academeia. But the great mass of men still prefer free social life, and individualism in gaining and spending; perhaps they always will. Though the plan itself of such an ideal State was felt by Plato himself to be unattainable, and was, indeed, profoundly modified by its author in the later and more practical dialogue, “The Laws,” yet a flood of instructive light is incidentally thrown on numberless problems of real life, political and social, as well as moral.

The opening scene has always been especially admired, the discussion on old age containing nearly all the best thoughts embodied three centuries later by Cicero in his essay, “De Senectute.” The rest of Book I. is less important, the various current definitions of justice being set up only to be bowled over, more or less fairly, by Socrates.

It is in Book II. that the ideal State, with its three classes, is interestingly developed. The division and subdivision of mechanical labor are advocated in phrases that often sound strangely modern.

Education is the especial subject of Book III. Poetry and music must be austerely and rigidly limited to the creation of better citizens. The attack directed at this point against the ignoble theology of Homer is a magnificent piece of literary criticism. Myths are to be invented expressly to justify the organization of the State. Individuals are to pass easily from one to another class, according to their fitness.

Already in Book IV. justice is defined as the force that keeps the three elements in equilibrium and each devoted to its proper functions. The analogy to the individual man is now elaborately pointed out. The conclusion is solemnly urged that justice is the only path to prosperity and happiness, whether for a State or a man. The original subject seems all but exhausted at this point.

The fifth book will shock nearly all readers. Socrates is here forced to explain in detail the plans by which he would destroy the family altogether, prevent each child from ever knowing who were his actual parents, and all parents from ever singling out their own offspring. Woman, to Plato, is but lesser man. She must share all gymnastic exposure and training, with the tasks of war, to the limit of her powers.

Books VI. and VII. discuss, in a higher and more mystical strain, the philosophic education of those who are to be the guardians of the commonwealth. The argument culminates in what we now call transcendentalism; that is, all the sensual phenomena of our world are but unsubstantial shadows of the eternal and divine realities, to which true education should direct the spiritual vision. At the beginning of Book VII. occurs the most famous of Plato’s similes. This world is likened to a cave wherein we sit as prisoners, facing away from the light, and seeing only distorted shadows of realities.

Books VIII. and IX. form, again, a single important section. Here the baser forms of commonwealth are treated as progressive stages of degeneracy and decay from the ideal State. The analogy with the individual man is still insisted upon at every stage. The whole discussion has close and practical relations with the actual history of various Greek city-States, and is full of political wisdom.

Book X. is largely taken up with a renewed attack upon poetry in what men still consider its noblest forms. Especially to be condemned, as we are told, is its effect in widening our human sympathies! Lastly, the rewards of justice are described. Since they are often clearly inadequate as seen in this life, the immortality of the soul, and the unerring equity of the Divine Judge, are revealed in a magnificent myth, or vision of judgment.

The thoughtful reader will prefer to keep his notebook in hand, and to build up for himself a much more detailed analysis. He should not fail to notice the consummate grace with which every transition in the wide-ranging discussion is managed, and often concealed. No one can or should read the “Republic” in a spirit of unquestioning approval. The furious assault by this great poet, myth-maker, and imaginative artist generally, upon his fellow-craftsmen in that guild must remind us that he is at times a perverse, even a self-contradictory doctrinaire. The proposal to dissolve all true family ties is a still more atrocious attack on the holiest and most helpful of human institutions. In regarding our earthly life as a mere purgatorial transition between two other and infinitely more important states of being, Plato again broke boldly with the prevailing Hellenic sentiments of his day. Here, however, the large Hebraic and Oriental element in the creeds of Christendom enables us to understand, often to sympathize with, utterances which then seemed novel and startling. In general, no thoughtful man or woman can turn the pages of the “Republic” without infinite enrichment and widening of mental range. It has had a great influence on all later visions of ideal States: but especially is this true, and indeed freely and frequently avowed, in the Utopia of Sir Thomas More.

The version of all Plato's works by Professor Jowett is the most important piece of translation made during the last generation, at least; it has added to our own literature a masterpiece of artistic form and manifold wisdom. The rendering is not slavishly literal, but all the more faithful to the spirit. In the "Republic" the style of Plato himself is usually so transparent that very little need of annotation will be felt. We may, however, in closing, mention a few helps for the special student of Plato. The chief standard work in English is Grote's "Plato and the other Companions of Socrates," in which each dialogue is carefully discussed. Walter Pater's "Plato and Platonism" is the best of brief compendiums. Zeller's "History of Ancient Philosophy," in German, or in English translation, is indispensable to the thorough student.

CONTENTS

Of Wealth, Justice, Moderation, and their Opposites |

1 |

The Individual, the State, and Education |

35 |

The Arts in Education |

66 |

Wealth, Poverty, and Virtue |

105 |

On Matrimony and Philosophy |

137 |

The Philosophy of Government |

176 |

On Shadows and Realities in Education |

209 |

Four Forms of Government |

240 |

On Wrong or Right Government, and the Pleasures of Each |

272 |

The Recompense of Life |

299 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

A Reading from Homer |

- Photogravure from the original painting

Early Venetian Printing |

136 |

- Facsimile of a frontispiece printed at Venice in 1521

Gemma Augustea |

209 |

- Photo-engraving from a sardonyx cameo

![]()

![]() This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

| Original: |

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |

|---|---|

| Translation: |

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |