Gustav Krist

Gustav Krist | |

|---|---|

| Born | 29 July 1894 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | 1937 Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation | Author, Traveler, Soldier |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Period | 1914 - 25 |

| Genre | History, Travel, Non-fiction, |

| Subject | Soviet Union, Russia, Persia, Afghanistan |

Gustav Krist (29 July 1894 – 1937) was an Austrian adventurer, prisoner-of-war, carpet-dealer and writer. His accounts of unmonitored journeys, in a politically closed and tightly-controlled Russian, and then Soviet Central Asia, offer valuable historical testimonies of the still essentially Muslim region before Sovietization, and the conditions there of the Central Powers prisoners-of-war during and after the First World War.

Background[edit]

The Viennese-born and educated Krist worked as a technician in Germany before being mobilised as a twenty-year-old private in the Austro-Hungarian Army on the outbreak of World War I.[1] Early in the war (November 1914) he was severely wounded and captured by the Russians at the San river[2] defensive line on the Eastern front. This led to nearly five years' internment in Russian Turkistan with other German and Austrian prisoners-of-war.

Internment[edit]

After a period of hospitalisation in Russia proper he had a sharp taste of the misery and hardship to come. He describes how he was one of only four survivors of a trainload of some three hundred prisoners-of-war who were sent from Koslov to Saratov in December, 1915, after the train-load was singled out for barbaric punishment for stealing wood to keep warm. He was only saved at this time by the intervention of Elsa Brändström of the Swedish Red Cross.[3]

His first internment camp in Turkistan was sited at Katta-Kurgan, a frontier town with the Emirate of Bukhara near Samarkand. With a natural gift for languages he took on the role of interpreter, building on some Russian and a smattering of various oriental languages he had acquired before the war. On this basis he was able to become familiar with the peoples, places and conditions of the region over the eight years he remained there. Conditions in the camps were harsh however. Many of his fellow prisoners died of typhus, forced labour and starvation, or in fighting following the collapse of the Central Government. Krist kept a diary of his experiences during the whole period written on cigarette papers and secreted in a Bukharan hubble-bubble pipe to avoid it being confiscated. After the Bolshevik revolution the region was both dangerous and politically confused as Soviets, White Army, Basmachi insurgents and foreign powers struggled for power.

This region of ancient Silk Road cities had been closed to foreigners on political grounds during the war. In 1917 Krist moved to Samarkand, where he worked in the town. Trading with the Sarts and being able to talk to them directly he had a sharp grasp of the situation. His writings offer a valuable glimpse of various peoples and cultures in this area of Central Asia. For seventy years after him the area was seldom visited by foreign visitors unencumbered by official controls and his accounts show life before the Sovietization of the region. Krist came to love the nomadic peoples of the region as well as the Islamic architecture of Samarkand, especially the Shah-i-Zinda complex

Various escapes[edit]

In 1916 Krist escaped Katta-Kurgan to Tabriz in Persia, but due to conditions in Kurdistan and British control of south Persia was unable to return to Austria. En route he had been recaptured but jumped a prison-train, made his way by Merv into northern Afghanistan and crossing into Persia went by Meshed to Tabriz.[4] As Tabriz was a principal centre for Persian carpet production and trade he began working there for a native Iranian in wool and carpets during which he travelled around Persia. Krist described being captured in the Russian military swoop on the German community in Tabriz which destroyed the German Club and German-owned PETAG (Persische Teppiche Aktien Gesellschaft) workshop[5] and was taken to Julfa and then Baku.

Following Krasnovodsk, from where inmates were sent to bury 1,200 Turkish prisoners-of-war on an island south of Cheleken who had died of starvation and thirst,[6] Krist was then sent to Fort Alexandovsky, an isolated penal-camp on the Caspian, where troublesome prisoners were concentrated.[7] The conditions there were atrocious, and eventually, when it was closed down following Red Cross investigations, he was moved to Samarkand,[8] where he was assigned work. After the Bolsheviks freed the prisoners of war, essentially stopping the issue of rations and opening the camp gates, Krist and others were left to fend for themselves and fell into establishing various wheeling-and-dealing industries.

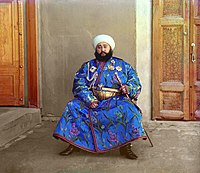

Krist also travelled with Red Cross delegations across Turkistan and in a bizarre episode entered the service of the Emir of Bukhara who was striving to re-establish his full independence in the collapse of the Russian Empire, and helped him set up a mint.[9] This was subsequently wrecked when Krist was driven out of town by the conservative religious leaders. Krist was able to visit the town and the Ark Citadel before its destruction. Bukhara fell to the Soviets under Mikhail Frunze in September 1920 after four days' fighting which left much of the town in ruins. Krist mentions the construction by the emir, using Austrian engineers, of a secret base at Dushanbe in the Tajikistan mountains. This was also bombed from the air by the Soviets and Krist visited the ruins on a later visit to the area.

The local soviet in Turkistan promised a train to take the ex-prisoners home in 1920 in return for aid in suppressing mutinous Bolshevik soldiers in Samarkand. Krist as an NCO led a force of Austrian POWs in disarming them, but after the Austrians had handed in their arms this agreement was reneged on. Krist was amongst those who were later condemned to death for counter-revolutionary activity. Luckily this was commuted to three-months imprisonment at the last minute leaving time to arrange a pardon. Krist and the remaining prisoners were repatriated late in 1921 through the Baltic States and Germany, having to cross a Russia suffering from famine and the Russian Civil War.

Adventurous return[edit]

After returning briefly to Vienna, in 1922 he moved back to Tabriz in Persia to work again as a carpet dealer, transversing Persia for the next two years. In time even this became routine and failed to satisfy his wanderlust. A chance meeting with some Turkmen tribesmen in 1924, led him to slip back across into Soviet territory, which was even then strengthening its controls along the frontier in that area.

Travelling without papers in Soviet territory was impossible. Krist said he'd "would sooner pay a call on the Devil and his mother-in-law in Hell" than attempt to travel without them. However borrowing the I.D. card of a naturalised fellow ex-prisoner in Turkmenistan he came up with a plan to get recognition as a State Geologist of the Uzbeg Soviet in Samarkand. This scheme enabled him to explore the mountainous region to the east without hindrance.

He crossed the waterless Kara-Kum desert (the “black, or terrible, one”) to the Amu Darya. Always a keen observer and with his gift for striking up conversations in Deh i Nau he fell in with a GPU officer who had witnessed the death of Enver Pasha.[10] After revisiting Bukhara, Samarkand and (pre-earthquake) Tashkent he moved up the Ferghana Valley. There he encountered the Kara Kirghiz (Black Kirghiz) with whom he wintered during their last annual migration into the Pamirs, before the Soviet forces rounded them up and they were collectivized. Working his way through modern-day Tajikistan he made his way to the Persian frontier and recrossed with some difficulty.

Final years[edit]

He returned permanently to Vienna in 1926 where he became editor of Die Teppichborse, a monthly carpet industry trade magazine.[11] Here, with some leisure time, and stimulated by occasional visits of former comrades, he pieced together his war diary as “Pascholl plenny!” (literally 'Get a move on, prisoner'). In 1936 his manuscript was accepted by a publisher, and this led to his writing the account of his 1924–1925 adventure later published as “Alone through the forbidden land”. He died as it came off the presses, as a result of the serious injuries he received during the war.[12]

Translator[edit]

Emily Overend Lorimer (1881–1949), Faber & Faber's translator of Krist's work, was a noted translator from the German language (including Krist's fellow Austrian Adolf Hitler[13]). She was also an Oxford philologist, editor of the "Basrah Times", 1916–17, during the First World War and with links to the Red Cross. She was the wife of David Lockhart Robertson Lorimer a Political Officer for the British Indian Political Service in the Middle East.[14][15][16]

Bibliography[edit]

- Pascholl plenny! (Wien: L. W. Seidel & sohn, 1936), translated by E. O. Lorimer as “Prisoner in the Forbidden Land”.

- Allein durchs verbotene Land: Fahrtenin Zentralasien (Wien: Schroll, 1937), translated by E.O. Lorimer as "Alone through the Forbidden Land, journeys in disguise through Soviet Central Asia": 1939.

- Buchara: oraz sąsiednie kraje centralnej Azji [i.e. Bukhara: neighbouring countries and Central Asia], volume 19 of Biblioteka podróżnicza (Warszawa: Trzaska, Evert i Michalski, 1937)

Other information sources[edit]

- Reader’s Union magazine. “Readers’ News” No. 20 (April 1939): Travel Special.

- Bailey, F. M. Mission to Tashkent (London: Jonathan Cape, 1946)

- Hopkirk, Peter. Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin's Dream of an Empire in Asia. (London: Kodansha International, 1984).

References[edit]

- ^ p. 2, Readers' Union, 'The man who went East' in Travel special, Readers' News No. 20 (April 1939)

- ^ p. 15, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 58, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 167, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 185, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 188, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 190, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 252, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 293, Krist, Gustav, Prisoner in the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber, 1938

- ^ p. 82, Krist, Gustav, Alone through the Forbidden Land, Faber and Faber/Readers' Union, 1939

- ^ p. 2, Readers' Union, 'The man who went East', in Travel special, Readers' News No. 20 (April 1939)

- ^ p. 2, Readers' Union, 'The man who went East' in Travel special, Readers' News No. 20 (April 1939)

- ^ India Office Records: Private Papers [Mss Eur F175 - Mss Eur F199], British Library

- ^ "Marriage" (PDF).

- ^ Tuson, P. (2003). Playing the Game: Western Women in Arabia. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-86064-933-2. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- ^ "Brunei Gallery at SOAS: Bakhtiari Kuch - Early European Travellers: Caricature Orientalists or just Men of their Time?". www.soas.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

External links[edit]

- 1894 births

- 1937 deaths

- Writers from Vienna

- 20th-century Austrian writers

- Austrian travel writers

- Austrian orientalists

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I

- World War I prisoners of war held by Russia

- Austrian prisoners of war

- Austrian escapees

- Escapees from Russian Empire detention

- Expatriates in Germany

- Expatriates in the Russian Empire

- Expatriates in Iran

- Explorers of Central Asia