Admiral Phillip/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

The causes which led to the colonisation of New South Wales—Cook's voyages, the overcrowded state of the English gaols (one consequence of the American revolution), the proposals of Matra, Sir George Young, and Sir Joseph Banks for forming colonies—can only be briefly referred to here.

Phillip has no place in the prologue to the story of the establishment of Greater Britain under the Southern Cross, and it is with Phillip only that this book has to do. Yet, for a proper appreciation of Phillip as a Builder, it is necessary to give some account of the share which those who were the architects of the structure actually had in the undertaking.

Ask ninety-nine out of every hundred persons, 'Who discovered Australia?' They will answer, 'Captain Cook.' The answer is, in a sense, correct, but the brilliancy of the great navigator's fame will lose nothing by the truth, and the truth is that he never even saw the site of the first settlement in the Antipodes. What the name of Columbus is to America, that should the name of Cook be to Australia, and although Phillip and his transports can scarcely be compared with the Pilgrim Fathers and the Mayflower, yet, as the pioneers of settlement in Australia, the officers of the First Fleet ought to be remembered as colonisers, with something of the same admiration we have for those sturdy Puritan adventurers.

Leaving out of the story the Portuguese and Dutch explorations on the western coast of Australia, something of the eastern coast was known (although not to Englishmen) a couple of hundred years before Cook's voyage. But Cook surveyed it and made it British territory; and the publication of the narrative of his voyage suggested schemes for its colonisation. One James Maria Matra in 1783, thirteen years after Cook's return from his Botany Bay voyage, submitted a proposal for colonising the new territory with American loyalists. Sir Joseph Banks, the naturalist who accompanied Cook, was, however, the man who not only had most to do with the matter, but until the day of his death in 1820 took the keenest interest in the colony's progress. Banks gave evidence before a Committee of the House of Commons which had been appointed in 1779 to inquire into the question of transportation, and spoke strongly in favour of Botany Bay as a place suitable for the purpose. Admiral Sir George Young was also consulted, and after many plans had been submitted and much time consumed, the Government decided to take action, and then left it to Lord Sydney, at this time Secretary of State for the Home Department, to carry out a modification of the various proposals which had been made.

That minister had to choose an officer to command the fleet of transports and govern the new territory, and little is known of the actual reasons for Phillip's selection. Presumably, however, he was appointed on his merits, as he appears to have had no private influence whatever with his superiors. On the 31st August 1786, Lord Sydney wrote to the Lords of the Admiralty a voluminous letter, dated from Whitehall, notifying them that His Majesty had been pleased to signify his royal commands that 750 convicts then under sentence of transportation and lying in the various gaols 'should be sent to Botany Bay, on the coast of New South Wales, in the latitude of 33° south, at which place it is intended that the said convicts should form a settlement.' Then followed an intimation that the Lords of the Treasury would provide means of conveyance, together with provisions and other supplies to keep these wretched outcasts of society alive, 'as well as tools to enable them to erect habitations, and also implements for agriculture.' A ship of war 'of a proper class'—how Phillip must have writhed when he learnt that it was the wretched Sirius—with a sufficient complement of officers and men, and another vessel of 200 tons as a tender, was to be ready simultaneously with the convict transports to act as convoy, and to prevent the prisoners overpowering the military guards on board the chartered vessels of the fleet. The letter is too long to be given here in detail, though the great results that attended this despatch of the 'First Fleet' lend it an importance that would not be accorded to a mandate of the Government ordering a fleet away on some warlike enterprise. The instructions to the Admiralty were explicit and complete, but Phillip was destined to gain to the full his bitter experience of red-tapeism before he sailed. The prisoners were to be put on board the various transports at sundry points in the Thames, whence Phillip was to convoy them to Plymouth, and at that port he was to pick up another ship with its load of felons. Further instructions were given that the fleet should, at the discretion of the officer commanding the expedition, call in at certain ports to provision and water the ships, the Cape of Good Hope being especially named as a place where fresh supplies could be obtained.

To secure due obedience and subordination from the convicts, and for the defence of the settlement against attacks by the natives, it was considered expedient to provide a small force of disciplined men, and '160 private marines, with a suitable number of officers and non-commissioned officers,' were to be so furnished. Solemn assurance was given that this force would be properly victualled after their landing—a promise which was not fulfilled—and another cheering intimation was given that such tools, implements and utensils as this body of men would have occasion for 'to render their situation comfortable … at the new intended settlement,' would be duly forthcoming. Then came the official chestnut—perhaps unintentional—for the marine cats to pluck, stating that the period of service, 'it is designed, shall not exceed a period of three years.'

With this letter was enclosed the 'Heads of a Plan' upon which the new settlement was to be formed, together with the proposed establishment for its regulation and government. It is unnecessary to reproduce this document in full, but some quotations from it may be given. The ships were to take on board as large a quantity of provisions as could be stowed—sufficient at any rate to last for two years. 'Supposing,' wrote Lord Sydney, 'one year to be issued at whole allowance, and the other year's provisions at half allowance, which will last two years longer.' The Government 'presumed' that by the end of that time the settlement, with the live stock and grain which might be raised by the common industry, would be able to maintain itself as far as food was concerned. The difference of expense, however, it was added, between this mode of disposing of the convicts of the country and that of the usual ineffectual one, was too trivial to be a consideration with His Majesty's Government, 'at least in comparison with the great object to be attained by it, especially now the evil' (the convict element) 'is increased to such an alarming degree, from the inadequacy of all other expedients that have hitherto been tried or suggested.'

The advantages likely to result to the new settlement from the cultivation of the New Zealand hemp or flax plant were then alluded to. The supply of hemp was of great consequence to Great Britain as a naval power—the production of hemp by felons has a certain suggestive humour—and already English manufacturers of rope and canvass believed that the New Zealand material made better canvass than that grown in Europe, and reported that a ten-inch cable of New Zealand hemp was superior in strength to one of eighteen inches made of the European plant. The Government had also no doubt but that 'most of the Asiatic productions'—none were specified—could be cultivated in the new colony, and that, in a few years after its foundation, recourse to European countries by England for such commodities would be unnecessary. The possibility of exploiting the vast kauri forests of New Zealand for masts and other ship-building purposes was next mentioned, such material being designed for the use of the navy in the Indian seas. The anticipations in regard to the cultivation of flax in the new colony, it may be stated, were never realised, but the export of timber from New Zealand soon became a great and profitable industry, and has so remained.

Lord Howe, First Lord of the Admiralty, duly replied to this letter, and in his reply said:—

'I cannot say the little knowledge I have of Captain Philips (sic) would have led me to select him for a service of this complicated nature. But as you are satisfied of his ability, and I conclude he will be taken under your direction, I presume it will not be unreasonable to move the King for having His Majesty's pleasure signified to the Admiralty for these purposes as soon as you see proper, that no time may be lost in making the requisite preparations for the voyage.'

This correspondence throws no light on the reasons for the appointment of Phillip. The position was one which it was scarcely likely many importunate friends of the Government would clamour for, and as the management of the colonisation scheme was practically left by Pitt and his Cabinet in the hands of their colleague, the Home Secretary, in the absence of evidence to the contrary. Lord Sydney should have the credit of having selected Phillip solely on his merits.

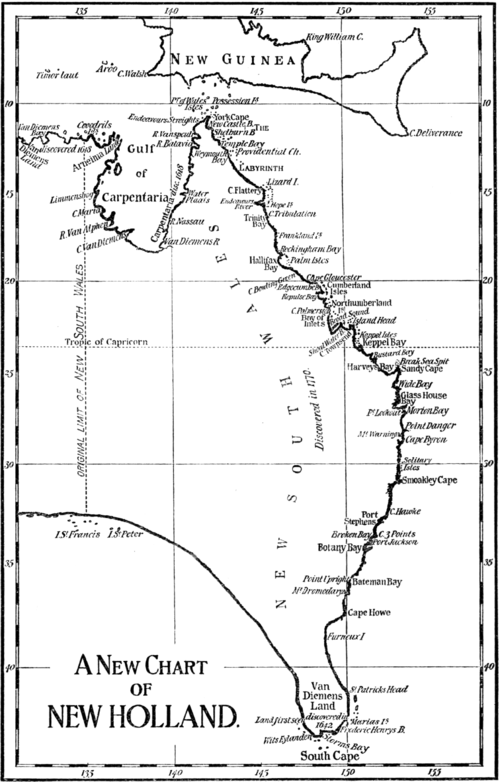

Map of the Eastern Half of Australia, shewing extent of Phillip's Government, 1787.

On the 12th October, the Lords of the Admiralty informed the Home Office that 'in obedience to His Majesty's commands, we immediately ordered the Sirius, one of His Majesty's ships of the sixth rate, with a proper vessel for a tender, to be fitted for this service; and … the ship will be ready to receive men by the end of this month.'

On the same date Phillip received a short commission appointing him Governor of New South Wales, but this was afterwards replaced by a longer and more formal document.

This last commission, dated 2d April 1787, appointed Arthur Phillip, Esquire, 'to be our Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief in and over our territory called New South Wales, extending from the Northern Cape or extremity of the coast called Gape York, in the latitude of 10 degrees 37 minutes south, to the southern extremity of the said territory of New South Wales or South Cape, in the latitude of 43 degrees 39 minutes south, and of all the country inland westward as far as the 135th degree of east longitude, reckoning from the meridian of Greenwich, including all the islands adjacent in the Pacific Ocean, within the latitudes aforesaid, etc., etc'

A reference to the map of Australia will show that the territory which Phillip was appointed to govern included about half the continent. It was not until ten years later that Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) was proved by Bass to be an island, and the 'South Cape' named in the commission, and still the name of the southernmost point of Tasmania, when Phillip's commission was drawn, was supposed to be part of the continent.

The commission, which gave Phillip all the usual powers, a short Act of Parliament, an Order in Council, the Letters Patent constituting the Courts of Law, and a Letter of Instructions, were all that the Governor had to guide him in conducting the enterprise to a successful issue.

The 'Instructions' order the Governor 'to fit himself with all convenient speed,' and land the 600 male and 180 female convicts, intended to form the new colony, as soon as possible at Botany Bay. Teneriffe, Rio de Janeiro, and the Cape of Good Hope are named as places where the ships were to refresh on their way out, and seed-grain and live stock were to be taken on board. The Governor is enjoined to be expeditious in getting the land into cultivation, to practise economy, to explore the coasts, to reserve ample land for further batches of convicts which were to follow, to protect the natives and endeavour to conciliate them, and to do many other things, which, when they are of interest, will be referred to hereafter. The concluding paragraph says:—

'And whereas it is our royal intention that every sort of intercourse between the intended settlement at Botany Bay, or other place which may be hereafter established on the coast of New South Wales and its dependencies, and the settlements of our East India Company, as well as the coast of China, and the islands situated in that part of the world, to which any intercourse has been established by any European nation, should be prevented by every possible means: It is our royal will and pleasure that you do not on any account allow craft of any sort to be built for the use of private individuals which might enable them to effect such intercourse, and that you do prevent any vessels which may at any time hereafter arrive at the said settlement from any of the ports before mentioned from having communication with any of the inhabitants residing within your Government, without first receiving especial permission from you for that purpose.'

This was penned only one hundred and twelve years ago. Now, besides the Orient, the Peninsular and Oriental, and the many other steamship lines running magnificent vessels to 'the settlement,' there are two German companies, a French and a Japanese company carrying on a regular service, and 10,000 ton steamers are dry-docked and floated again within twenty-four hours at a part of 'the settlement' which, long after Phillip landed in it, remained unpeopled.