Archaeological Journal/Volume 2/Usages of Domestic Life in the Middle Ages. The Dining Table (Part 2)

USAGES OF DOMESTIC LIFE IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

THE DINING-TABLE.——PART II.

We take the first opportunity to continue our remarks on the ancient dining-table and its appendages.

Those of our forefathers who were opulent enough had plates and dishes of silver, although "treen," or wooden, spoons and platters for the table held their place for many a day in the domestic offices of the great and the dwellings of the humble. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries pewter[1] was applied to the manufacture of similar articles, but the price of that metal, which continued high even till the early part of the eighteenth century, prevented the general use of it among the lower classes. Harrison in his description of England, written about 1580, adverting to the reputation of English pewterers, says, "in some places beyond the sea a garnish of good flat English pewter of an ordinarie making, . . . . is esteemed almost so pretious, as the like number of vessels that are made of fine silver; and in maner no lesse desired amongst the great Estates, whose workmen are nothing so skilful in that trade as ours." He tells us the "garnish" contained twelve platters, twelve dishes, and twelve saucers, and that its price varied from sixpence to eightpence the pound[2]; an excessive value when compared with that of beef and mutton at the same period.

Convenience of form as well as long usage have so accustomed us to round plates, that we may well be surprised they should ever have been made angular; yet they were frequently copies, in a more precious material, of the square wooden trencher of the kitchen: at the same time circular plates are often represented in old drawings of feasts. Dishes were much of the same form as at present; the largest were called "chargers," and seem to have been shaped like shallow bowls.

The salt, that important and stately ornament of the middle-age table, was a conspicuous object before or on the right hand of the master of the house[3]. It appears in various shapes: sometimes as a covered cup on a narrow stem; occasionally in a castellated form; and at the caprice of the owner or maker it frequently took the figure of a dog[4], a stag, or some other favourite animal. The annexed cut represents a large silver salt of the early part of the seventeenth century, preserved among the plate at Winchester College; although of comparatively recent date, there is every reason to believe it was fashioned after a more ancient type. The three projections on the upper rim seem to have been intended for the support of a cover, perhaps a napkin, as it was considered desirable to keep the cover clear of the salt itself: "loke that youre salte seller lydde touche not the salte," saith the "boke of keruynge." It appears from numerous allusions to the fact, that the state salt was used by the "sovereign" or entertainer only; and it is not unlikely, from the great number of salts mentioned in old inventories, that when possible each guest also had one for his particular use. It is not easy to understand how any one at the upper or cross table could be seated "below the salt," as it was not customary to sit at the lower side of that board, which was left unoccupied for the more convenient access of servants. The probability is, therefore, that this phrase, and the distinction it inferred, applied only when the company sat on both sides of a long table, where the position of a large salt marked the boundary of the seats of honour, or what may be termed the dais of the board.

So long as people were compelled to the occasional use of their fingers in dispatching a repast, washing before as well as after dinner was indispensable to cleanliness, and not a mere ceremony. The ewers and basins[5] for this purpose were generally of costly material and elaborate fabric:—

"L'eve demande por laver,

Li vilains maintenant lor baille

Les bacins d'or, et la toaille

Lor aporte por essuier."

The will of John Holland, duke of Exeter, date 1447, mentions "an ewer of gold, with a falcon taking a partridge with a ruby in its breast[6]."

In the days of chivalry it was high courtesy towards a guest to invite him to wash in the same basin:—

"Puis fist on les napes oster

Et por laver l'iaue aporter;

Li Chevalier tout premerains

Avec la Comtesse ses mains

Lava, et puis l'autre gent tout."

This however was perhaps a species of compliment naturally attendant on the equivocal honour of eating from the same plate with your host[7], though it should be observed, in justice to the poets who are our veracious authorities for the custom, that there was generally a lady in the case:—

"Trestot delez li, coste a coste,

Lo fet seoir la damoisele

Et mengier à una escuele."

We may now glance at the drinking-vessels of ancient days. The warriors of the north drank from horns, as did the Homeric heroes ages before them, and as the people of most countries have done where horn-bearing animals were known. In the ninth century the Saxon king of Mercia gave the monks of Croyland his "table-horn, that the elders of the monastery might drink out of it on feast days, and sometimes remember in their prayers the soul of Wiglaf the donor[8]." The same Wiglaf gave to the refectory of Croyland his gilt cup, embossed on the exterior with "barbarous victors fighting dragons," which he was wont to call his "crucible," because a cross was impressed on the bottom, and on the four angles of it[9]. This was doubtless a specimen of that skill in working precious metals for which the Anglo-Saxons were famous, and for the exercise of which Eadred in 949 rewarded his goldsmith Ælfsige with a grant of land[10]. Horns continued to be appendages of the table until after the Conquest, although other drinking-vessels were in use also. We see them represented on the Bayeux Tapestry, and find from wills and other notices that they lingered on the board, or in the hall, for centuries after the date of that historic needlework. The mouth of the horn was not unfrequently fitted with a cover, like the old- fashioned Scotch mull. In the collection of antiquities in the British Museum is preserved a very large drinking-horn of the sixteenth century, so great indeed that it was evidently intended to try a man's capacity for wine. It is formed of the small tusk of an elephant, carved with rude figures of elephants, unicorns, lions and crocodiles, and mounted with silver: a small tube ending in a silver cup issues from the jaws of a pike whose head and shoulders inclose the mouth of the vessel. The following legend is engraved upon it:—

"Drinke you this and think no scorne

All though the Cup be much like a horne."

1599. Fine s.

The remains of an iron chain are attached to this horn, which was probably suspended in the hall of some convivial squire of the old time, whose guests were at times summoned to drain it, or to pay a shilling fine.

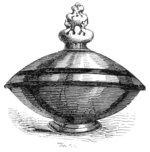

After the horn the commonest drinking-vessel of early times was, perhaps, the mazer-bowl; its name was undoubtedly derived from the maple wood[11], of which it was usually made, although like bowls of more costly material bore the same appellation, which seems ultimately to have been given to shape, without reference to substance. Mazers were of different sizes, great and little being named in the same inventories; sometimes they had covers[12], and a short foot or stem. The early wassail-bowl seems to have been shaped as a mazer. We give a cut of the "murrhine cup," presented to the abbey of St. Albans by Thomas de Hatfield, bishop of Durham, "which," says the recorder of the benefaction, "we in our times call 'Wesheyl[13].'" This vessel could not have been used in a very graceful manner; we perceive from illuminations that small ones were raised to the mouth in the palm of the hand; the larger sized would have needed both hands. The small mazer was called a "maselin," unless, indeed, Dan Chaucer borrowed this diminutive from the Latin to make a rhyme:—"They fet him first the swete win,

And mede eke in a maselin."

Our ancestors seem to have been greatly attached to their mazers, and to have incurred much cost in enriching them. Quaint legends, in English or Latin, monitory of peace and good-fellowship, were often embossed on the metal rim and on the cover; or the popular, but mystic Saint Christopher engraved on the bottom of the interior, rose in all his giant proportion, before the eyes of the wassailer as he drained the bowl, giving comfortable assurance that on that festive day, at least, no mortal harm could befal him. But we may believe that occasionally art made higher efforts to decorate the favourite cup. Witness Spenser's musical and vivid description of

"A mazer ywrought of the maple warre,

Wherein is enchased many a fayre sight

Of bears and tygers, that maken fiers warre;

And over them spred a goodly wilde vine,

Entrailed with a wanton yvy twine.

Thereby is a lambe in the wolves jawes;

But see, how fast renneth the shepheard swain

To save the innocent from the beastes pawes,

And here with his sheepehooke hath him slain.

Tell me, such a cup hast thou ever seene?

Well mought it beseeme any harvest queene."

The latest of our poets who alludes to it is Dryden: in the seventeenth century it may have been still in use among the humbler classes. The annexed cut represents a very perfect mazer[14] of the times of Richard the Second; its material is a highly polished wood, apparently maple, and the embossed rim of silver gilt[15] bears this legend:—

"In the name of the trinite

fille the kup and drinke to me."

It was customary to give names to particular drinking cups. Edmund earl of March, in 1380 bequeathed his son Roger a hanap of gold with a cover, called "Benesonne[23];" a name which is usually considered to have belonged to the "grace-cup." In 1392 Richard earl of Arundel and Surrey left his wife her own goblet called "Bealchier." Sir John Neville bequeathed to the abbey of Hautemprise in 1449 a cup called "ye Kataryne[24]." Large standing cups, as they were called, intended chiefly for the ornament of the table or dressoir, but also for wine, had their names; John, baron of Greystock, who died in 1436, left to Ralph his son and heir a very large silver cup and cover, called the "Charter of Morpeth[25]," a term which may recall to the reader's recollection the ruby ring, described as the "Charter of Poynings" in the will of Sir Michael de Poynings in 1368[26]. Besides these standing vessels, which were of large capacity, for we find them called "galoniers" and "demi-galoniers[27]," the table or buffet was decorated with silver "drageoirs," or "dragenalls" as they were named in England, for spices, made in many quaint shapes.

The most curious appendage however of the tables of princes and noblemen of high rank was the Ship, (nef,) which according to Le Grand, held the napkin and salt of its owner[28]: it may have done so, but there is little or no proof of the destination of this singular ornament, which by some antiquaries is conjectured to have been a box for spices and sweetmeats. The form of it was evidently borrowed from the navette, (naveta,) a ship-like vessel in which frankincense was kept on the Altar, and which may be traced to a greater antiquity than the table-ship. The use of the nef in England seems to have been less common than on the continent. The earliest mention of it in this country, of which we are aware, is in the inventory of the jewels of Piers Gaveston, in 1313. "Item a ship of silver with four wheels[29], enamelled on the sides." Among the royal jewels in the 8th of Edward the Third, 1334, was "a ship of silver with four wheels, and a dragon's head, gilt, at either end;" it weighed xij.li, vij.s. iiijd.[30] There are other species of ships named in old wills, as in that of William of Wykeham, 1403, "an alms-dish newly made in the form of a ship[31];" in that of John Holland, duke of Exeter, 1447, "an almes-diss the shipp;" and in that of George earl of Huntingdon, 1534, "a flat ship of silver gilt." These, perhaps, corresponded in intention with the alms-pots[32] (pots à ausmosne) into which, says Le Grand, pieces of meat were thrown from the table to distribute among the poor[33]. It is out of our power to elucidate further the purpose of the table-ship, but we incline to believe it was intended for confections and spices, and not for the salt. The annexed illustration, a servant bearing the ship to table, is taken from an elaborate illumination of the fifteenth century, representing a feast given by Richard the Second[34].- ↑ The company of Pewterers was incorporated 20th Jan. 1474; 13 Edw. IV.

- ↑ Prompt. Parvul., ed. Way, V. Garnysche; Holinsh. Chron., vol. i. p. 237.

- ↑ "The boke of keruynge;"—"than set your salt on the ryght syde where your souerayne shall sytte and on ye lefte syde the salte set your trenchours."

- ↑ Two are named in the will of Edmund Mortimer, earl of March, A.D. 1380; also "un saler en la manere d'une lyoun ove le pee d'argent susorrez." Roval Wills, pp. 112—114.

- ↑ In Strutt's Horda, vol. i. Pl. xvi. fig. 3, is an engraving of a Saxon drawing re- presenting Lot entertaining the angels: an attendant bears a vase-shaped basin for washing, together with a long narrow maniple. which hangs over his left arm, and is fringed at the ends.

- ↑ Royal Wills, p. 284. In the inventory of the jewels of Edward the Third, is "a silver gilt ewer, triangular, enamelled with the images of the three kings of Denmark, Germany, and Aragon." Archæologia, vol. x. p. 252.

- ↑ For a more oppressive exercise of hospitality in old times the curious reader may consult St. Foix, "Essais Historiques sur Paris," vol. i. p. 98.

- ↑ Codex Diplom. Ævi Saxonici, vol. i. p. 305. Mr. Kemble suspects the authenticity of this charter; it is at any rate of great antiquity.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., vol. ii. p. 299.

- ↑ Dutch maeser. In that valuable record of the usual household effects of the middle classes at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the assessment of a 15th upon the borough of Colchester, in the 29th of Edward the First, (Rot. Parl., i. 245,) mazers are frequently mentioned—"i. ciphus de mazero parvus pretii vj.d."—"i. ciphus de mazero pretii xviiid."—the highest value at which one is assessed being two shillings, and that price must have been owing to its size and workmanship, for had the material been silver, the fact would have been stated. These we may fairly assume to have been wooden bowls.

- ↑ "One mazer with one cover duble gilt weyth xxix onces,—ix.li. xiij.s. iiij.d."—Wills and Inventories (Surtees Society), p. 339.

- ↑ MS. Cotton. Nero D. vii. fo. 87.

- ↑ "One mazer wth one edgle of sylver." Wills &c. (Surtees Society), p. 415.

- ↑ In the possession of Evelyn Philip Shirley, Esq., M.P., who has kindly permitted it to be engraved for this paper.

- ↑ Prompt. Parvul. ed. Way, tom. i. p. 268.

- ↑ "Item, quatre barils de Ivoir, garniz de laton, od les coffins." Inv. of Piers Gaveston, A.D. 1313. Fœdera. "Duo barilli argenti deaurati cum zonis argenti minutis, pond, in toto xls." Wardrobe account 8 Edw. III. A.D. 1334. Cotton MS. Nero, C. viii. fo. 319b.

- ↑ Prompt. Parvul. cd. Way, sub voce.

- ↑ Warton's Hist. of English Poetry, vol. ii. p. 254.

- ↑ Testamenta Vetusta, p. 231.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 78.

- ↑ Ibid., passim.

- ↑ Royal Wills, p. 112. The writer cannot help thinking that this name, literally "blessing," was given to objects which had been left with the blessing of a testator, The following passages seem to yield a clue to its origin:—"Item, une coupe d'or, enamaille od perie, que la Reigne Alianore devisa au Roi, qui ore est, od sa beniceon." Inv. of Piers Gaveston, A.D. 1313. John duke of Lancaster bequeathed to his son the duke of Hereford, afterwards Henry the Fourth, "un fermaile d'or del veile manere, et escriptz les nons de Dieu en chescun part d'ycelle fermaile, la quele ma tres-honour dame et mier la reigne qe Dieu assoille me donna, en comandant qe jeo le gardasse ovecqe sa benison, et voille q'il la garde ovecqe la benison de Dieu et la mien." Royal Wills, p. 157.

- ↑ Testamenta Vetusta, p. 265.

- ↑ "Ciphum maximum." Wills and Inventories (Surtees Society), p. 85.

- ↑ Test. Vet., p. 73.

- ↑ Will of Cardinal Beaufort, Royal Wills, p. 325.

- ↑ Vie Privée. vol. iii. p. 188.

- ↑ So we venture to amend "roefs," the word as printed in the Fœdera for "rotes," or "roets."

- ↑ Cotton MS. Nero C. viii. fo. 319.

- ↑ Test. Vetust., p. 767.

- ↑ "Olla argentea magna costata pro elemosina, cum capite regis ex una parte et capite episcopi ex altera, ponderis xv. li. xlij.s. iv.d." Wardrobe Acc. 8 Edw. III., Cotton MS. Nero C. viii. fo. 319.

- ↑ Vie Privée, iii. 255. The alms-pot still holds its place in the hall of Winchester College: broken meat is placed in it for distribution to the poor, and it is under the management of one of the foundation scholars, who is styled "ollæ præfectus."

- ↑ Royal MS. 14 E. IV. fo. 244 b.