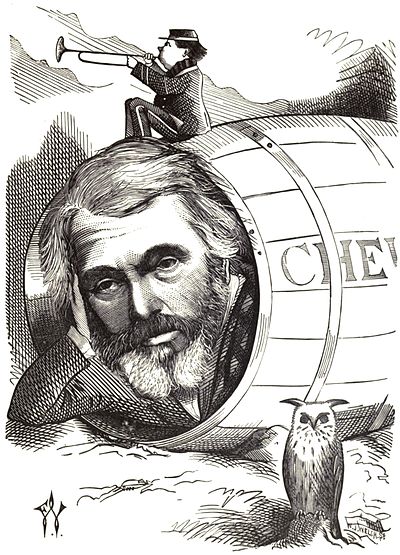

Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day/Thomas Carlyle

THOMAS CARLYLE.

Thomas Carlyle, the 'Philosopher of Chelsea,' and one of the most prominent and original writers of his time, was born almost in the last lustrum of the last century. At Ecclefechan, in Dumfriesshire, he first saw the light, on the 4th of December 1795. All we can attempt will be to jot down some of the more noteworthy incidents in his life. To try to criticise the writings, to make a correct estimate of the genius of Carlyle, and endeavour to indicate his future place among the writers of his age, would take a volume, if the work were fairly done. Most writers who have had him under notice have said this, and in their next paragraph have fallen into vulgar abuse or more vulgar panegyric. Another trick we have seen nearly every writer of an essay on Carlyle fall into is imitation of his uncouth style and unwarrantable words. Some of the reviewers have gone farther than this: they have tried an imitation of his ideas. This last effort has been a signal failure. He is original. But every reader of his works who has the slightest respect for the language which was sufficient for the needs of a Milton, a Shakespsare, or a Burke, will heartily regret that the Chelsea philosopher ever went to live in Germany, or, at least, that he ever departed from the simple and flowing style of his earliest works; as, for instance, 'The Life of Schiller,' published in 1824. However, it is too late now for criticisms on his style to be of any use. His works are written; and, as they are full of great thoughts, the ugliness of their diction will always be forgotten in the originality, truth, and power of their matter.

A LATTER-DAY PHILOSOPHER.

This most disagreeable drudgery to a man of his genius he quitted in two years to become a professional writer. In this capacity he furnished sixteen articles for Brewster's 'Edinburgh Encyclopædia.' Perhaps the highest praise that can be given to encyclopædia articles written half a century ago is to say that they are worth reading now. He also translated at this time 'Legendre's Geometry,' to which he added a preface on Proportion. In 1824 his German studies bore fruit. 'Wilhelm Meister,' in English, from his pen, appeared in that year.

In 1826 he married, and removed from Edinburgh shortly after to a small estate at Craigenputtock. Dumfriesshire. Here he led a life of seclusion, devoted to study, and writing for the 'Edinburgh,' the 'Westminster,' the 'Foreign Quarterly,' and 'Fraser's.' He lived at Craigenputtock eight years, and then removed, in 1834, to Cheyne-walk, Chelsea, which has been his home for thirty-eight years.

In 1837 he began to give lectures in public. These lectures were continued for several years, and the subjects dealt with were German literature, literary history, 'Revolutions of Modern Europe,' and, in 1840, 'Heroes and Hero Worship.' As a lecturer, our philosopher was remarkable for rough vigour, masterlike handling of his subject, and rude language to his audiences. The last, no doubt, did them good, and did not displease them. They paid to hear and see a nineteenth-century Diogenes, and they got their money's worth, and something more.

Carlyle was made Lord Rector of the University of Edinburgh in 1866, and his speech to the young men of his Alma Mater was one of the finest ever spoken from the Lord Rector's chair. It was in this year that his wife died. This sad event was a great shock. They had been married for forty years; and the epitaph her husband placed on her tombstone is one of the most eloquent and loving memorials ever penned. He came out in August of the same year to defend Governor Eyre from the attacks of his enemies. But his last public appearance of importance was as the writer of the article, 'Shooting Niagara: and After?' which was published in 'Macmillan' just after the passing of the Reform Bill.