Character of Renaissance Architecture/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

THE DOME OF FLORENCE

The great dome of the cathedral of Florence marks the beginning of the Renaissance movement in architecture, though in its general form and structural character it has no likeness to ancient domes, and has few details drawn from the Roman classic source. It exhibits a wide departure from any previous forms of dome construction, and is an expression of the creative genius of a remarkably gifted man of great independence, working under inspiration drawn in part from ancient sources, in part from mediæval building traditions, and in still larger part from the new motives that were beginning to animate the artistic ambitions of the fifteenth century.

The dome of the Pantheon and the dome of St. Sophia, the two greatest domes of former times, had been built on principles that did not admit of much external effect, and the numerous smaller ones of the Middle Ages, in western Europe, had been equally inconspicuous externally, if not entirely hidden from view, in consequence of rising from within a drum which reached far above the springing level. In most cases the whole construction was covered with a timber roof, so that from the outside the existence of a dome would not be suspected. This was a secure mode of construction, and one that for stability could not be improved ; but it did not give the imposing external effect that Brunelleschi sought.

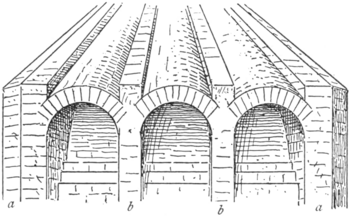

Attempts to make the dome a conspicuous external feature had indeed been made before Brunelleschi's time. The later Byzantine builders had raised small domes on drums resting on pendentives, and rising above the main roof of the building, but they had still carried these drums up somewhat above the springing of the dome, and had further fortified them with buttresses built over the supporting piers, as in Hagia Theotokos of Constantinople (Fig. 1). Thus in such designs the dome still remains partly hidden from view, the drum being the most conspicuous part of the composition. Among the early domes

Fig. 1.—Hagia Theotokos.

of western Europe is that of Aachen (Fig. 2). In this case the drum is carried up far beyond the springing, and is covered

Fig. 2.—Aachen.

with a timber roof which completely hides the dome from external view. The same adjustment of the dome to its drum is, with minor variations of form (the dome being in some cases polygonal on plan, as at Aachen, and in some cases hemispherical) found in most other mediæval domes, and the timber roof over all is likewise common. But in a few cases a different scheme was adopted in which the dome is set on the top of the drum instead of within it. In such cases, however, the drum is low, not rising above the ridge of the timber roof of the nave, and the dome, being unprovided with abutment, is

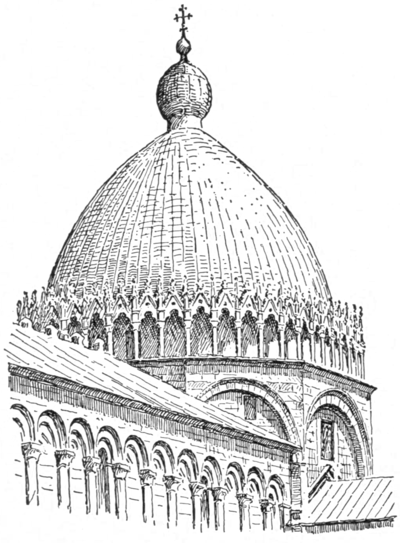

Fig. 3.—Dome of Pisa.

insecure except in so far as it may have a form that is self-sustaining as to thrusts (which removes it from the true dome shape), or may be secured by some kind of binding chain.[1] An example of such a dome occurs on a small scale over the crossing of the cathedral of Pisa (Fig. 3). This dome is not hemispherical, its sides rise steeply, and with such moderate curvature as to render it measurably self-sustaining as to thrust.[2] Another instance of a similar scheme, and on a larger scale, is that which appears to have formed a part of Arnolfo's design for the cathedral of Florence. This dome was never executed, and our knowledge of it is derived from the well-known fresco in the Spanish chapel of Santa Maria Novella.[3] Here both the dome and the drum are octagonal in conformity with the plan of the part of the building which it covers. The outline (Fig. 4) is slightly pointed, but the sides

Fig. 4.—Dome of Arnolfo.

are nevertheless so much curved in elevation that a structure of this form would not stand without strong cinctures. It is, however, not unlikely that the fresco painter has given it a more bulging shape than Arnolfo intended. But domes of this character were exceptional in the Middle Ages. The builders of that epoch confined their practice for the most part to the safer form in which the vault is made to spring from within the drum, and is thus necessarily, either in part or entirely, hidden from external view.

A remarkable dome of this latter class is that of the Baptistery of Florence, which, though the building has undergone various superficial transformations since its original construction at an early, though uncertain, epoch, has come down to us in essential integrity. This building on plan is in the form of an octagon, and the dome is of corresponding shape, and sprung

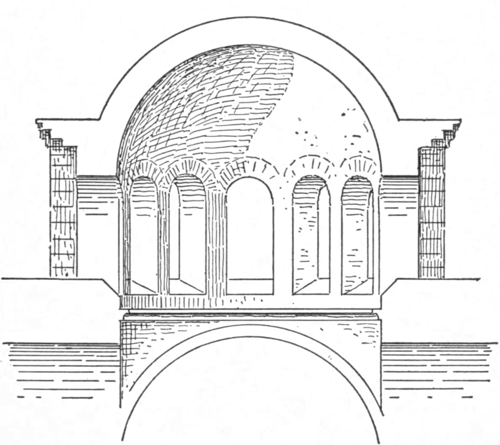

Fig. 5.—Section of Baptistery.

Such were the models of mediæval dome building accessible to Brunelleschi when he was forming his great scheme for the covering of the octagon of the cathedral of Florence. But the idea of a low dome, or a hidden dome, could not meet the wishes of the Florentines of the fifteenth century. Their civic pride and large resources called for an imposing design which should make the dome a dominant architectural feature of their city. It was decided that it should be raised upon the top of a high drum, and the task to which Brunelleschi appHed himself was to fulfil this requirement.

Of the vast and soaring dome which he succeeded in erecting many opinions have been held, but all beholders are impressed with its grandeur. It has been common to speak as if the master had been chiefly inspired by the ancient monuments of Rome, and had taken the Pantheon as his principal model.[6] But although he came to his task fresh from the study of the ancient Roman monuments, and undoubtedly had the Pantheon much in mind, yet the dome which he produced has little in common with that great achievement of imperial Roman constructive skill. In general it follows, though with great improvements as to outline and proportions, the scheme of Arnolfo as illustrated in the fresco of the Spanish Chapel; but the model to which it most closely conforms, notwithstanding the obvious and essential points of difference, is that of the Baptistery just described. There can, I think, be little question that this monument supplied the chief inspiration and guidance to both Arnolfo and Brunelleschi. A comparison will show that the dome of the cathedral, with its supporting drum, is, in fact, little other than a reproduction of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in a modified form, and enlarged proportions, raised over the crossing.

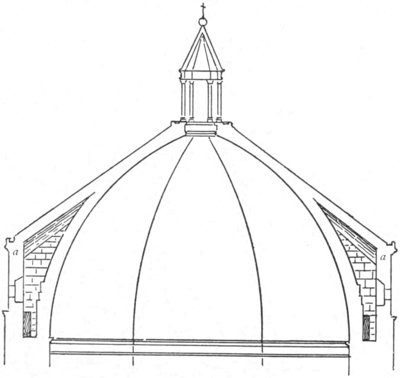

But while taking the scheme of the Baptistery as the basis of his own scheme, Brunelleschi was obliged to make some daring changes in order to give his design the external character which he sought. This great dome (Plate I), like that of the Baptistery, is octagonal in plan and pointed in elevation. It rises from the top of the octagonal drum, and consists of two nearly concentric shells of masonry, with an interval between them. Eight vast ribs of stone rise from the angles of the drum and

Plate1

Dome of Brunelleschi |

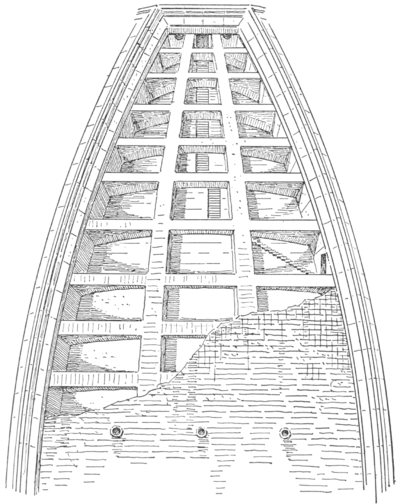

converge on the curb of an opening at the crown. These ribs extend in depth through the whole thickness of the double vault and unite its two shells. Between each pair of these great ribs two lesser ones are inserted within the interval that divides the two shells, and nine arches of masonry, lying in planes normal

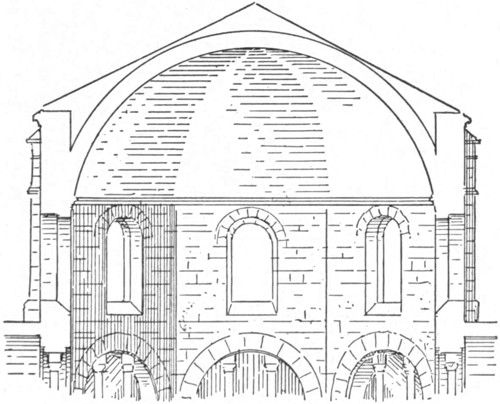

Fig. 7.—System of the dome.

to the curve, are sprung between the great ribs and pass through the lesser ones on each side of the polygon (Figs. 7 and 8), while a chain of heavy timbers (a, Fig. 8, and Fig. 9), in twenty-four sections, clamped together at the ends with plates of iron, binds the whole system between the haunch and the springing. So much of the internal structure can be seen in the monument itself, but further details are described in Brunelleschi's own account of what he intended to do.[7] From this

Fig. 8.—Section. |

Fig. 9.—Part Plan. |

we learn that the base of the dome, which was to be built solid to the height of 5¼ braccia, was to consist of six courses of long blocks of hard stone (macigno) clamped with tinned iron and upon this were to be chains of iron.[8] Mention is also made of a chain of iron over the timber chain ("in su dette quercie una catena di ferro"); but no such chain is visible in the monument, and if it exists, it must be embedded in the masonry of the vault, like the chains at the base.

It will thus be seen that while Brunelleschi's scheme is essentially different from that of the Baptistery, its structural system is little more than an ingenious modification of it. The parts of the one answer to those of the other with singular completeness. The attic wall and pyramidal roof of San Giovanni are transformed into the external shell of the cathedral dome, the angle buttresses of the older monument become the great angle ribs of Brunelleschi's vault. The intermediate abutments of the Baptistery are changed into the intermediate ribs of the great dome, and the inclined barrel vaults of the Baptistery scheme are represented in the cathedral dome by the arches sprung between the great angle ribs.

It has been thought by some writers that the rib system of the dome of Florence gives the structure a somewhat Gothic character, and it is sometimes called a Gothic dome.[9] But there can be no such thing as a Gothic dome. It is impossible for a dome of any kind to have the character of a Gothic vault. The difference between the two is fundamental. A Gothic vault is a vault of concentrated thrusts, and it requires effective concentrated abutments. A dome is a vault of continuous thrust, and for sound construction it requires continuous abutments, as in the Pantheon. Whatever use the ribs of Brunelleschi's vault may have, they do not, and cannot, perform the function of the ribs in Gothic vaulting. Their use is to strengthen the angles of the dome, and to augment its power of resistance to the weight of the lantern which crowns it. They do not support the vault as the ribs of a Gothic vault do. Being composed of very deep voussoirs, they have more strength to withstand thrusts, as well as to bear crushing weight, than the enclosing shells have, and thus to some extent they may hold these shells in. But it appears plain that the architect did not feel confidence in their power to perform this function without reenforcement by a chain, or chains, which, in his own words, "bind the ribs and hold the vault in" (che leghino i detti sproni e cingano la volta dentro). However this may be, the ribs of a dome cannot have any function like that of the ribs in Gothic vaulting. The shell of a Gothic vault is not held in by the ribs, nor is it in any way incorporated with them. Both shell and ribs are held in by the buttresses. This point will be considered further in connection with the dome of St. Peter's.

The whole scheme of this dome was a daring innovation of one man, and in this it differs from former architectural innovations, which were the comparatively slow outcome of corporate endeavour, progressive changes being so gradual that no wide or sudden departures from habitual modes of building were made at any one time, or by any one person.

It was a prodigious undertaking. The span of the dome is nearly a hundred and forty feet, the springing level is a hundred and seventy-five feet above the pavement, and the height of the dome itself, exclusive of the lantern, is about a hundred and twenty feet. Such a project might well appall the most courageous of building committees, and we need not wonder that the Board of Works drew back in dismay when it was first laid before them.[10]

The successful accomplishment of the work, and the stability which it has thus far maintained, show that the architect was a constructor of great ability,[11] and the fact that he managed to raise the vast fabric without the use of the ponderous and costly kind of centring that had been commonly employed in vaulting, makes the achievement still more remarkable. The precise manner in which he did this is not clear, but of the fact there appears no question.[12]

The dome of Florence is indeed a remarkable piece of construction, and it is no less remarkable as a work of art. In beauty of outline it has not, I think, been approached by any of the later elevated domes of which it is the parent. Yet with all of its mechanical and artistic merit, the scheme is fundamentally false in principle, since it involves a departure from sound methods of dome construction. A bulging thin shell of masonry on a large scale cannot be made secure without abutment, much less can such a shell sustain the weight of a heavy stone structure like the lantern of this monument, without resort to the extraneous means of binding chains. A builder having proper regard for true principles of construction in stone masonry would not undertake such a work. For although it may be possible to give the dome a shape that will be measurably self-sustaining as to thrusts, as Brunelleschi clearly strove to do,[13] it is not possible to make it entirely so, and therefore if deprived of abutment it must be bound with chains. But a structure of masonry which depends for stability on binding chains is one of inherent weakness, and thus of false character.[14]

From these considerations it appears to me that Brunelleschi led the way in a wrong direction, notwithstanding the nobility of his achievement from many points of view. And in following his example modern designers of elevated domes have wandered still farther, as we shall see, from the true path of monumental art.

Moreover, when we consider that a dome set within its drum is not only stronger, but that it is also much better for interior effect, the dome of the Pantheon still remaining the grandest and most impressive arched ceiling of its kind in the world, the unbuttressed modern domes, with their manifold extraneous and hidden devices for security, appear still less defensible.

But in the architectural thought of the Renaissance little heed was given to structural propriety or structural expression, and the Italian writers, who have largely shaped our modern architectural ideas, have not only failed to recognize the inherent weakness of such a building as the dome of Florence, but have even considered the work praiseworthy on account of those very characteristics which make it weak. Thus Sgrilli lauds Brunelleschi for having had the "hardihood to raise to such a height the greatest cupola which until its time had ever been seen, upon a base without any abutments, a thing that had not before been done by any one."[15] And Milizia says, "It is worthy of special notice that in the construction of this cupola there are no visible abutments."[16]

As to the permanent stability of this dome various opinions have been held by the experts among the older writers.[17] Its form is, as we have seen, as favourable to stability as it would be possible to make that of any vault which could be properly called a dome. It appears to the inexperienced eye as stable as a crest of the Apennines. Every precaution as to material and careful workmanship seems to have been taken to make it secure. The wall of the drum on which it rests is five metres in thickness, and the solid base of the dome itself is built, if the architect's scheme was carried out as he had stated it before the Board of Works, of large blocks of hard stone, thoroughly bonded and clamped with iron. The lower system is sufficiently strong, and appears to rest on a solid foundation. But nevertheless there are ruptures in various parts of the structure which have caused apprehensions of danger,[18] and its future duration must be regarded as uncertain. The writers who have maintained that it is secure have argued on the assumption that the parts of a dome all tend toward the centre.[19] These writers overlook the fact that the force of gravity above, especially when the dome is heavily weighed by a lantern, neutralizes the inward tendency of the lower parts and causes a tendency in those parts to movement in the opposite direction. This neutralizing force is lessened by giving the dome a pointed form, as Brunelleschi has done, but, as before remarked (p. 22), it can hardly be overcome entirely so long as any real dome shape is preserved.[20]

It may be thought that the object which Brunelleschi had in view, of producing a vast dome that should be an imposing feature of the cathedral externally, justifies the unsound method of construction to which he resorted (the only method by which the effect that he sought could be attained). But structural integrity is, I think, so fundamental a prerequisite of good architecture that in so far as this gifted Florentine was obliged to ignore sound principles of construction in order to attain an end not compatible with such principles, the result cannot be properly considered as an entirely noble and exemplary work of art, however much beauty and impressiveness it may have.

The example set by Brunelleschi was, in point of construction, a pernicious one, and bore fruit of a still more objectionable character in the works of other gifted men less scrupulous than he, and less endowed with mechanical ingenuity, as we shall see farther on.

Though there is nothing whatever of classic Roman character in this great dome, the lantern which crowns it, built from Brunelleschi's design after his death, has classic details curiously mingled with mediæval forms. Its eight piers are adorned with fluted Corinthian pilasters surmounted by an entablature, while the jambs of the openings have engaged columns carrying arches beneath the entablature in ancient Roman fashion. From the entablature rises a low spire with finials set about its base, and flying buttresses, adorned with classic details, are set against the piers. None of the classic details have any true classic character, nor has the ornamental carving, with which the composition is enriched, any particular excellence either of design or execution. But these details are invisible from the ground, and in its general form and proportions the lantern makes an admirable crowning feature of this finest of Renaissance domes.

- ↑ The elevated domes of Arabian architecture are in many cases constructed of wood and stucco. When of masonry they are, I believe, either weighted within where the thrusts fall, or are bound with chains.

- ↑ I have not examined the dome of Pisa closely on the spot, but I suppose it is bound with a chain, as we know was the custom at a later time. Cf. Fontana, vol. 2, p. 363.

- ↑ There can be little doubt that the dome represented in this fresco embodies the original project of Arnolfo, though this has been questioned. Cf. Guasti, Santa Maria del Fiore, etc., Florence, 1887, pp. lx-lxi.

- ↑ This needs to be qualified. The thrusts of the dome being continuous logically call for continuous abutment, as in the Pantheon, but the intervals between the abutting members are so small that the resistance is practically continuous.

- ↑ By its architectural character, I mean its character as a work of art. By the term "architecture" we properly mean not building merely, but the fine art of beautiful building.

- ↑ This has been based on the affirmations of Vasari, who states that it was Brunelleschi's purpose to "restore to light the good i.e. the ancient Roman] manner in architecture," and that he had "pondered on the difficulties" involved in vaulting the Pantheon. Cf. Le Opere di Giorgio Vasari, Milanesi edition, Rorence, 1880, vol. 2, p. 337.

- ↑ A copy of this document is said to have been preserved for some time in the archives of the Board of Works, but it seems to have disappeared subsequently. It is given, however, by several writers, Vasari and Guasti among them. There are slight differences of wording and of measurements between the transcripts of these two authors. That of Guasti is the most intelligible, and seems to agree best with the monument. It reads as follows: "In prima: la cupola, dallo lato di dentro lunga a misura di quintoacuto, negli angoli sia grossa nella mossa da piè braccia 3¾, e piramidalmente si muri; sicchè nella fine, congiunta con l'occhio di sopra, che ha a essere fondamento e basa della lanterna, rimanga grossa braccia 2½. Facciasi un' altra cupola di fuori sopra questa, per conservarla dallo umido, e perche la torni più magnifica e gonfiata; e sia grossa nella sua mossa da piè braccia 1¼, e piramidalmente segua, che insino all' occhio rimanga braccia ⅔.

"El vano che rimarrà da l'una cupola all' altra, sia da piè braccia 2: nel quale vano si metta le scale per potere cercare tutto tra l' una cupola e l' altra; e finisca 'l detto vano a l' occhio di sopra braccia 2⅓.

"Sieno fatti ventiquattro sproni, che otto ne sieno negli angoli e sedici nelle faccie: ciascuno sprone negli angoli grosso dappiè braccia sette. Dalla parte di dentro, e di fuori, nel mezzo di detti angoli, in ciascuna faccia, sia due sproni; ciascuno grosso dappiè braccia quattro; e lunghe insieme le dette due volte, piramidalmente murate insieme insino alia sommitS. dell' occhio inchiuso dalla lanterna, per iguale proporzione.

"I detti ventiquattro sproni con le dette cupole sieno cinti intorno di sei cerchi di forti macigni, e lunghi, e bene sprangati di ferro stagnato; e di sopra a detti macigni, catene di ferro che cingano d' intorno la detta volta, co' loro sproni. Hassi a murare di sodo, nel principio braccia 5¼ per altezza; e poi seguano gli sproni, e dividansi le volte.

"El primo e secondo cerchio, alto braccia 2; e 'l terzo e quarto, alto braccia 1⅓; e 'l quinto e sesto cerchio, alto braccia 1: ma 'l primo circhio dappiè sia, oltre a ciò, afforzato con macigni lunghi per lo traverso, si che l'una volta e l'altra della cupola si posi in su detti macigni.

"E nell' altezza d' ogni braccia 12, o circa, delle dette volte, sieno volticciuole a botte tra l'uno sprone e l'altro, per andito alia detta cupola; e sotto le dette volticciuole, tra l'uno sprone e l'altro, sieno catene di querela grosse, che leghino i detti sproni e cingano la volta dentro; e in su detti quercie una catena di ferro.

"Gli sproni murati tutti di pietra di macigno e pietra forte, e le facce della cupola tutte di pietra forte, legate con sprone insino all' altezza di braccia 24: e da indi in su si muri di mattoni o di spugna, secondo che si delibererà per chi allora l' avrà a fare, piu leggieri che pietra.

"… Murinsi le cupola nel modo di sopra, senz' alcuna armadura, massime irsino a braccia 30; ma da indi in su, in quel modo che sarà consigliato e deliberato per quei maestri che l' avranno a murare: perchè nel murare la pratica insegna quello che si ha da seguire."—Guasti, La Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, 1857, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ Durm, Die Dom Kuppel in Florenz, etc., Berlin, 1887, Plate 1, gives an admirable illustration of the internal system of this remarkable dome, and shows the masonry of the solid base with its clamps and chains, as described in the document quoted by Guasti (note, p. 18).

- ↑ This idea finds expression in the latest work that I have seen on the subject: Die Kuppel des Domes Santa Maria del Fiore zu Florence. Von Paul Wenz, Berlin, 1901, p. 52; also in Durm, Die Baukunst der Renaissance in Italien, p. 406.

- ↑ For a full account of the deliberations held, as well as for much else of importance relating to the building of this dome, see Professor C. E. Norton's Church Building in the Middle Ages, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1880.

- ↑ But while Brunelleschi appears to have had great natural constructive aptitude, he had not had a sound training or experience in construction. Such training would have taught him that it would not do, under any circumstances, to spring a vault from the top of a wall, and he ought to have learned this from his study of the ancient Roman monuments.

- ↑ Nelli, Discorsi di Architettura, Florence, 1753, p. 74, reproduces an old drawing which purports to show the form of the scaffolding that Brunelleschi employed. This drawing bears the following inscription: "Questa Dimostrazione è di Filippo Brunelleschi Architetto fatta per e Ponti della Cupola di S. M'ra. del Fiore di Firenze nell' Anno M.CCCCXIX e fu quella che mostrò quando fu lasciato in libertà di dover esser solo nell' operazione di d.ª cupola senza il Ghiberti suo compagno non avendola voluta dar fuori prima di non essere libero Architetto di da Opera; come sentiranno nella sua Vita scritta da Diversi." Brunelleschi, in his account of his intentions before the Board of Works (note, p. 19), would not explain his scheme for the scaffolding. He said merely that the vault was to be raised, without centring, to the height of 30 braccia, and from that level upwards, in the manner that should be advised by those who might then have the work in charge.

- ↑ In his explanation of his scheme before the Board of Works, as given by Vasari, Brunelleschi begins as follows: "Considerato le difficultà di questa fabbrica, magnifici Signori Operaj, trovo che non si può per nessun modo volgerla tonda perfetta, atteso che sarebbe tanto grande il piano di sopra, dove va la lanterna, che mettendovi peso rovinerebbe presto." Op. cit., vol. 2, p. 347.

- ↑ It may be thought that this would condemn the use of metal clamps in masonry, such as were inserted in the walls of the Parthenon, or the wooden ties that were, in some cases, used in parts of Gothic buildings. But there is a wide difference between such use of clamps and ties, and the binding chains of the great domes of the Renaissance. In the Greek and Gothic work the masonry forms are favourable to stability independently of the clamps and ties. These were inserted either for security against unusual dangers, as from earthquakes, or for temporary security against rupture while the work was in progress, before the interaction of the parts of the system was fully established; but a dome without abutment violates the constant conditions of stability.

- ↑ Discrizione e Studj dell Insigne Fahbrica di S. Maria del Fiore, Florence, 1733. p. xxi.

- ↑ Memorie degli Architette, etc., Florence, 1785, vol. i, p. 190.

- ↑ Fontana, Nelli, Cecchini, and others.

- ↑ These ruptures were first observed in the year 1693 (Nelli, op. cit., p. 13), and it was then advised by the architect Carlo Fontana to add a new chain of iron. Nelli, however, argued that the fissures had not arisen from thrust, but were due to a slight yielding of the foundations, and he urged that no chain be added, but that a bit of marble be dove-tailed into the vault across the opening, in order that any further movement might be detected by the breaking of this marble. For three years no further sign of disturbance was noticed, but a slight earthquake in 1697 broke a portion of the masonry of the outer face of the dome opposite the fissure across which the marble had been placed. It appears, however, to have been concluded that there was still no danger from thrust, and no new chain was inserted. Cecchini (Opinione intorno lo Stato della gran Cupola del Duomo di Firenze, published together with Nelli's Discorsi, etc., p. 82) speaks of several cracks in both the inner and the outer shells of the vault, and also in the supporting piers, even down to the ground. But he agrees with Nelli in attributing these to movements of the foundations from which he concludes that no further danger is to be apprehended, and he affirms that the structure is entirely safe.

- ↑ Cf. Nelli, op. cit., p. 73.

- ↑ The thrusts of a hemispherical dome are, in some degree, restrained by the binding of its continuous courses of masonry under compression, but this is not enough for security, as experience has shown; and in a polygonal dome, like Brunelleschi's, there is no such binding force, because there are no continuous circles of masonry.