Confiscation in Irish history/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV

THE CONFISCATION OF CONNAUGHT AND ORMOND

There remained of purely Irish territories untouched by confiscation or English settlement the province of Connaught less the County of Leitrim, Clare and the districts east of the Shannon in Tipperary and Limerick which had formed down to the time of Henry VIII. part of the Kingdom of Thomond, the MacCarthy lands in west Cork and south Kerry, Monaghan and some districts in Down and Antrim, and some small parts of Leinster.[1] From time to time we hear of the possibility of further plantations in these districts; but it was left to the energetic Strafford to take any effective steps in this direction.

The main facts of Strafford's confiscation of Connaught, and of his abortive scheme for a plantation are well known.[2]

In 1228, Henry III., after the death of Aedh King of Connaught, had treated that province as forfeited to the Crown, and had granted twenty-five cantreds to Richard De Burgo, retaining five in his own hands.[3]

These five, comprising most of the modern Roscommon, with parts of Sligo and Galway, after a complicated series of grants and regrants to some of the O'Conors and to various colonists, finally were left in the effective occupation of three great Irish clans, the MacDermotts, the O'Conors and the 'Kelly s, who held them in defiance of any efforts of the Crown to subdue them.[4]

The remaining twenty-five passed, with the rest of the great De Burgo inheritance, to the Mortimers, and so ultimately, on the accession of Edward IV,, to the Crown.

But with the extinction of the De Burgo earldom the Irish recovered possession of many districts, including the whole of the present County Sligo. Two illegitimate offshoots of the De Burgo house divided between them the lordship of the lands making up the present Galway and Mayo, and held their territories without any regard to the Mortimers. They gradually adopted Irish ways; so did the innumerable junior branches of the De Burgo family, and the descendants of the lesser lords, D'Exeters, Prendergasts, Nangles, &c. who had settled in Connaught in the thirteenth century. In particular succession to their lands began to be by tanistry in the case of the leading men; and the lesser landowners divided up their lands among all their sons, approximating to, if not actually adopting the Irish practice of gavelkind. The Earls of Ormond and the Earls of Kildare still maintained shadowy claims to great tracts from which all the settlers had been expelled by the Irish.

Thus in the time of Henry VIII. the right of the Crown to Connaught was legally beyond a doubt. No Connaught landowner could have a valid title unless he could show a grant from the Mortimers or the De Burgos, and unless the descent to him had been in accordance with the Common Law.[5] There can have been but few landowners in Connaught who fulfilled both these conditions.[6]

Henry VIII. entered into indentures with most of the Connaught lords of both races, the effect of which was to receive them as subjects, and, at least implicitly, to recognize their claims to land. To the Upper MacWilliam Burke, or De Burgo, he gave the title of Earl of Clanrickard, and a grant in general terms, under which the new earl claimed only the demesne lands actually in his possession, and rents and services from the lesser chiefs and freeholders in the territory subject to him.[7] O'Shaughnessy, lord of a small district round Gort, also obtained a grant which in his case was interpreted as conveying to him the lands of his clan.[8]

Sir Henry Sidney when Deputy about 1570 induced most of the Connaught lords to surrender their lands with the object of obtaining regrants with a clear title by letters patent. Nothing, however, was done for some years until, in 1585, under Sir John Perrot, a commission was sent down which made a settlement known as the Composition of Connaught.

The object aimed at was threefold. First a fixed revenue was to be secured to the Crown. Secondly the uncertain extortions, the "cuttings and spendings" of the chiefs were to be done away with, and the chiefs were to be compensated by grants to them and to their heirs by English law of the castles, lands and fixed rents and services which had hitherto descended according to Tanistry. Finally every landowner, chief or clansman was to be given a legal title to his own.[9]

This was a perfectly fair and square transaction. The inhabitants admitted that as against the Crown they had no legal title, the Crown admitted that equitably the inhabitants should have such legal title, and promised to grant it. The Crown title was not based on any surrender by the chiefs but on known facts; there appeared to be no loophole by which another title could be found for the Crown enabling it to tear up the Composition.

The Lords Justices and Council in 1641 maintained that the Composition was only an arrangement as regards revenue, and that it was never intended to give legal titles to the landowners.[10] But this is contradicted plainly by the wording of the various indentures, and the intentions of the government are set out in a letter from Walsingham with reference to MacWilliam of Mayo—"to give each chief his own, with a salvo jure to all others that have right."[11]

Indentures were made with the chief lords and gentlemen of each territory, which arranged the main outlines of the settlement, what the Queen was to have, and what each lord was to get in compensation for his cuttings, spendings, and uncertain customary duties. Inquisitions were to be taken before juries of the inhabitants to ascertain what each landholder was entitled to, and then letters patent were to be made out, giving to each man what was his own.

The troublous times which followed prevented the proper carrying out of this settlement. Valid grants were not made out by the Crown, and the inhabitants often failed to fulfill the conditions of the composition. The province was greatly involved in the rising under O'Neill and O'Donnell; but all treasons and rebellions were completely wiped out by James I. on his accession.

Thirty years after the Composition, and twelve years after his accession, in July, 1615, James wrote directing that letters patent should be made out to every freeholder in Connaught and Clare as was intended at the making of the Composition in Elizabeth's reign. Accordingly we find in the Calendar of Patent Rolls James I. long lists of grants to Connaught owners.[12] In some instances, no doubt to save expense, the lesser proprietors joined together, and empowered one of the leading men to take out letters patent to their estates in trust for them.[13] The result was the creation in Connaught, alongside of the great estates of the chief men, of what was in many cases a virtual peasant proprietary.[14]

The Lords Justices in 1641, still bent on opposing the "graces," and clinging with narrow fanaticism to the idea of a plantation in Connaught, endeavoured to gloss over the meaning of James' order. They declared first that Perrot's Composition was merely a composition in lieu of cess with the Crown, and was not any engagement upon the Crown for any interest in their lands in respect of the composition, and secondly as to King James' letter of 1615 they do not think the demand of the Connaught landowners just, as the composition was not really a grant of thus begging the whole question.[15] It is quite evident from the documents themselves that the Composition of 1585 and James' letter of 1615 plainly intended to give legal titles to all concerned.

To make the grants valid it was necessary to have the surrenders and grants enrolled in the Court of Chancery. From the list of grievances sent in, in 1624, by the landholders of the Pale we learn that the province of Connaught, after excessive charge for passing their lands, cannot now have their surrenders enrolled, and for want of the enrolment of the surrender they threaten to overthrow the whole ground, and thus defeat the inhabitants of the benefit of His Majesty's gracious intent. To this it was answered:—It is by default of the parties in neglecting the enrolment of their surrenders; and therefore it now rests wholly with His Majesty to give warrant for new letters patent.[16]

Among the "graces" asked for in May, 1628, number (29) is "that the inhabitants of Connaught, Thomond and Clare forthwith have their surrenders enrolled in the most beneficial manner possible, and that the passing of patents be carried through on terms favourable to the tenants." To this the answer of the Lords' Committee appointed to investigate and report on the concessions asked for was "The tenants of Connaught, Thomond and Clare should have their surrenders enrolled in the Chancery, according to the wish of James I. and shall receive new patents at half fees" … furthermore an Act should be passed finally confirming their tenures.[17]

It is asserted by Leland (Book IV. Chap. 8) that the inhabitants actually had paid £3,000 to have their patents enrolled, and that it was due to the neglect of the clerks of the Court of Chancery that this had not been done.

From time to time we come across hints at a possible plantation of Connaught. And from about 1625 on we hear of a project of confiscation and plantation in the Irish districts in north Tipperary and Limerick.[18] It was reserved for Strafford, as I have said, to bring both projects into the sphere of reality with his usual thoroughness.

The Parliament of 1634 had passed an Act confirming all compositions made or to be made by Strafford's new Commission for remedying defective titles.[19] It had asked for an Act under which sixty years' possession should give a good title as against the Crown. This would have proved fatal to any projected plantations; hence the Parliament was dissolved in 1635 before such xin Act could be brought in, and before the graces promised in 1628 had been confirmed.

In July, 1635, Commissioners were sent to Connaught to establish the title of the Crown. It was plain that on a legal quibble all or most of the patents granted under James I. were invalid. But the natives could and did point out that James in 1615 and Charles in 1628 had intended to secure the landholders in their estates. This argument was brushed aside on the ground that James' letter had been obtained on false pretences, for he had believed, or was supposed to have believed, that the conditions laid down in Perrot's Composition had been adhered to, whereas it was notorious that they had been violated in many cases. So James had been deceived, and his letter and the grace of 1628, based on it, might be set aside without dishonour to the King. Furthermore, Strafford denied that the inhabitants in Elizabeth's day had had any interest which they could surrender to the Queen, or compound for, as they were all mere intruders on the lands of the Crown.

On these lines it was easy to make the Crown's title evident. The juries of Sligo, Roscommon and Mayo yielded to government threats and found the verdicts required.

But in Galway a sterner resistance was met with. The landowners there had the powerful support of the old Earl of Clanrickard, a man of noted loyalty, connected by marriage with the new official nobility—he had married Walsingham's daughter, and was step-brother to the Earl of Essex—and at the moment resident in England, Stiffened by his support the Galway jury refused to find for the Crown.

But the line they took was a curious one. The Crown title started from the conquest of Henry II., and an alleged grant of his to Roderick O'Conor, King of Ireland and Connaught, with a subsequent forfeiture and grant to De Burgo. The jury found that the acquisition of Henry 11. was not a conquest, but a submission of the inhabitants, that the grant to Roderick was merely a composition whereby the King had only the dominium, but not the property of the lands. In both of these contentions they were undoubtedly right. But they apparently ignored the later dealings of John and Henry III. with Connaught which were the true foundation of the De Burgo title, and they started what looks a mere quibble when they found that, in tracing the descent to Edward IV., proof had not been made of Lionel, Duke of Clarence's possession (he had married the De Burgo heiress), and that the Statute of Henry VII. related to tenures rather than to lands. And when called on to declare in whom the freehold was vested (if not in the Crown) they refused to do so.[20]

The jurors were dealt with after the approved Tudor and Stuart methods of treating recalcitrant landowners. They were sentenced to pay £4,000 fine each, and to be imprisoned until they paid it; furthermore they were to acknowledge their fault on their knees and in open court. The high sheriff was sentenced to pay £1000, and was thrown into prison, where he died. Finally, to punish the general body of landowners, they were to lose one-half of their lands in the plantation, instead of one-fourth as originally intended. Terrorised by these measures another jury found a title for the Crown in April, 1637.

The penalties were afterwards reduced or wholly remitted; and in particular the idea of taking one-half of their property from the Gal way landowners was given up.

We learn from Carte that, as soon as the King's general title was found, an Act of the Council ordered that all who were possessed of lands in virtue of letters patent should enjoy their estates provided they produced their patents. Several did so and all were disallowed on the ground that the tenures in the patents were by common knight's service which was not warranted by the Commission. They were therefore voided as having been made in deceit of the Crown.

Those of Clare then immediately acknowledged the King's title to that county.[21]

Strafford writing from Limerick in August, 1637, to Lord Conway and Kilultagh says that "His Majesty is now entitled to the two goodly countries of Ormond and Clare … 'with all possible contentment and satisfaction of the people. In all my whole life did I never see, or could possibly believe to have found, men with so

George Philip & Son. Ltd.

|

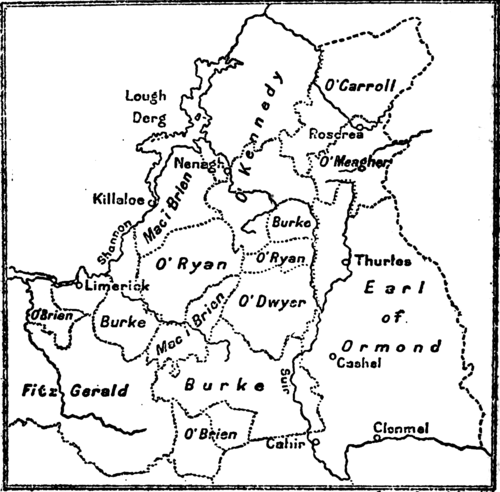

MAP V. |

By Ormond, in the above extract, is meant the whole district in north Tipperary and the adjoining part of Limerick inhabited by Irish clans.

Theobald Walter, ancestor of the house of Ormond, had got from King John a grant of five and a half cantreds of land, comprising the northern half of the modern Tipperary, Ely O'Carroll, now in King's County, and some districts now in Limerick. These territories had been fairly well conquered and settled, although in the hilly districts the Irish were never thoroughly mastered.

In the fourteenth century the Irish recovered the greater portion of the lands included in Theobald Walter's grant, though needless to say his descendants, who had meanwhile established themselves firmly in south Tipperary, still maintained their claims.[23]

The Statute of Absentees vested all the lands of the heirs general of Thomas, seventh Earl of Ormond, in the Crown. But they were regranted to Piers, heir male of the family, and this grant was confirmed by a private Act of Parliament, 30 Henry VIII.

Henry VIII. had entered into indentures with all the Irish clans in these regions, and had thus implicitly recognized their position. The Ormond claims had become somewhat theoretical; apparently the Earls contented themselves with chief rents from the Irish occupiers, and with the recovery of the castles of Nenagh and Roscrea and some adjoining lands.[24] Their rights seem to have been entirely ignored in the various dealings with Ely O'Carroll. And James I. had given grants to several of the chiefs including in them fixed payments from the freeholders in lieu of the Irish uncertain exactions, thus recognising the clansmen as landowners.

But legal ingenuity was able to set aside all claims of the natives. They were intruders on the possessions of Englishmen—as a matter of fact the O'Briens of Ara certainly, and the O'Ryans and O'Kennedys probably, were really intruders, who had seized in the 14th century lands never previously held by them. Hence they had no title as against the Ormonds, and the Statute of Absentees had vested the Ormond title in the Crown. Then they had no title against the Crown, for no length of possession could avail against the King. And finally if they abandoned law, and pleaded that that their long standing possession gave them an equitable claim to consideration they were told that since their lands had descended by gavelkind, and since that custom had been declared illegal, none of them could prove any real long standing title to the lands in their possession.[25]

There remained the title of the Earl of Ormond. There is a certain amount of doubt as to whether Henry's grant to Earl Piers had really included the whole of the lands in question.[26] Ely had been dealt with apparently without any reference to the Ormond rights, and the case of Ara seems also doubtful. Now the Crown lawyers seem boldly to have contended that none of these lands had been included in the grant. The Patent was not to be found in the ordinary rolls, although it was in the memoranda rolls of the Exchequer, and still exists; and they were unaware of the existence of the Act 30 of Henry VIII. confirming it. Therefore when the project of a plantation was first started it was supposed that no effective opposition could be offered by the Earl of Ormond.

But as a matter of fact the Ormonds had all the title deeds, and so were in a very strong position, as the Crown lawyers were acting more or less in the dark.

Earl Walter "of the Rosaries" had died before any effective steps had been taken towards a plantation, complaining bitterly that in spite of the eminent loyalty of his family he should be the first of the old Anglo-Norman blood marked out for spoliation.

His grandson and successor in the title, afterwards the great Duke of Ormond, was more prudent, or rather more selfish. His actual revenues from the disputed lands were small. He was promised special favours at the expense of the Irish under the plantation scheme for himself, and some two or three of his friends. Therefore he forebore to produce Henry VIII. 's grant, and in 1637 a jury at Clonmel found a title for the King.[27]

The troubles in Great Britain put a stop to any effectual proceedings in Connaught and Ormond. Before any of the landowners in these districts had been deprived of their lands, the English Parliament had deprived Strafford of his head.[28] And Charles was beginning to see that the loyalty of Irish Catholics might be worth cultivating as a support against the growing disloyalty of Scottish Presbyterians and English Puritans.

In March, 1641, he wrote confirming the "graces," and suggested that a Bill should be brought in for confirming sixty years' titles in Connaught and Ormond. Borlase and Parsons, the Lords Justices, protested against this and still urged a plantation. Nothing was done by July, when Parliament was prorogued. Before it met the great rebellion of 1641 had broken out. We cannot doubt that one of the contributory causes to it was the treatment of the landowners of Connaught, Clare and Ormond.

The confiscation and projected plantation in these districts never took effect, although a complete survey, now unfortunately lost, was made of all the lands affected; and after the Restoration the title of the Crown to Connaught was expressly renounced.[29] Its importance in Irish history is that it marks a progressive decline in the morality of English dealings with Ireland.

The statesmanship of the Tudors had, on the whole, been regardful of the rights of the Irish. They had utilised to the full the right of the sword, but they had seldom stooped to mere legal quibbles as a pretext for spoliation.

James I., or his advisers, had in his early years followed this course. Alongside of much injustice we find conscientious endeavours to deal fairly with those in actual occupation of land. But as time goes on we find a deterioration in the moral standard. The distinction between old Irish and old English is revived, to the disadvantage of the former; grasping officials have almost a free hand as regards extortion; musty parchments are brought to light in support of titles long forgotten. Matters become worse under Charles I. Neither old Irish nor old English are safe. Puritanism increases in high places, and at the same time to enrich himself seems to be one of the chief duties of a high official. It is unfair to apply to the 17th century the moral standards of the present day; yet if we read Mr. Bagwell's Ireland under the Stuarts, we can hardly fail to be struck by the fact that he seems to look on dishonesty as a norm^al quality of the official of the period. No doubt "the reason of state" can be invoked in defence of a good deal of this. An Irish Catholic with land seemed undoubtedly more dangerous than one without any; and English Kings had not yet realised that Puritanism was incompatible with loyalty. They were soon to be terribly undeceived; but in the meantime they had planted in Ireland a body of men hostile to the throne, while they had alienated those on whom they might have relied for its defence.

- ↑ The majority of the landowners in Mayo, as well as those in about half of Galway were of course really of old English descent; but they had practically all become to all intents and purposes identical with the old Irish.Monaghan had been divided amongst the clansmen first under Elizabeth and again under James. The barony of Farney was in possession of the Earl of Essex.

- ↑ It is noticeable that the Calendars of State Papers have very few references to Strafford's proceedings with regard to Connaught. Mr. Bagwell gives a pretty full account.

- ↑ Knox: History of Mayo, p. 55. The dealings of the Kings of England with Connaught previous to this year are most confusing; a full account of them can be found in Knox.

- ↑ The best account of these transactions is in Knox, History of Mayo. Leitrim and Cavan were not included in the De Burgo grant as they were held to form part of De Lacy's grant of Meath.

- ↑ An Act, 10th of Hy. VII.. had declared that it should be lawful for the King to enter into all manors, &c. of the lordship of Connaught in cases where no discharge of the King's interest could be proved. Several reputed freeholders were at the same time got rid of, after confessing that they had no right to their lands. Lds. Justices and Council to Vane. Cal. St. Paps., 1641, p. 275.

- ↑ The head of the Blake family was able to do so. See Blake Family Records.

- ↑ For grant to E. of Clanrickard see Cal. St. Paps., 1606, p. 310.

- ↑ The Books of Survey and Distribution show that in 1641 the then O'Shaughnessy owned the whole clan territory.

- ↑ It is curious to find how completely some recent authors of pronounced pro-Irish tendencies have failed to grasp the real meaning and effect of the Composition of Connaught. Even D'Alton appears to miss the point that the clansmen were to be secured in their shares of the clan lands.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1641, p. 275.

- ↑ Quoted in Iar Connaught, p. 107.

- ↑ From p. 330 on.

- ↑ Pat. Rolls, James I., p. 348. Here about eighty proprietors in Connemara empowered Morrogh na Moire O'Flaherty to procure grants to himself of lands lately surrendered by them which were found by inquisition to be their property.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., Ap. 1631, p. 606. Sir J. Jephson to Lord Dorchester. "The Counties of Mayo, Sligo, and Roscommon, which it is proposed to plant, are covered with thousands of families owning from £5 to £12 yearly value."See also Books of Survey and Distribution.

- ↑ The Connaught landowners claimed in 1641 "that the King is bound in honour to settle them in their lands, first by the composition made in the time of Q. Elizabeth, secondly by the letter of James I. of 21st July, 1615, and thirdly by the "graces" of 1628. Cal. St. Paps., 1641, p. 275.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1624, p. 507.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1628, p. 330.Leland says: "The surrenders were made, their patents received the great seal, but by the neglect of the officers neither was enrolled in Chancery."In Cal. St. Paps., 1647—60, Addenda, under 1635, Sir C. Coote is said to have been the person who neglected to enrol the surrenders, p. 213.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1625, p. 73: suggestion to plant Lower Ormond. Ibid., 1629, p. 536. "People talk of planting the territories of Ormond, Arra, Owneymulrian, Ikerrin and Kilnamanagh. The King's title is good, and the gentry there are ready for a plantation." Lord Esmonde to Lord Dorchester. There are many other allusions to the project.A possible plantation of Connaught is spoken of in Cal. St. Paps., 1631, p. 612; also p. 639: it was proposed to deduct one-fourth from all who had over 200 acres, "but that all that have less, the said fourth being deducted, shall have all taken from them."

- ↑ This commission differed very much from that set up by James. It aimed at raising revenue by finding flaws in titles, and compelling the owners to pay fines for new titles, or increased quit rents.

- ↑ Carte: Life of Ormond.

- ↑ While the references to the plantation of Connaught and Clare are very few in the printed Calendars of State Papers there are numerous allusions to various projects for the plantation of Ormond and the adjoining Irish districts.

- ↑ Cal. St. Paps., 1637, p. 168.

- ↑ The O'Carrolls held Ely: the O'Meaghers Ikerrin; the two baronies of Ormond belonged to the O'Kennedys. O'Ryan had Owneybeg in Limerick, and part of Ara and Owney in Tipperary; another O'Ryan had Kilnalongurty in the modern Kilnamanagh Upper: Ileagh in the same barony was held by MacWalter Burke. Kilnamanagh Lower, with part of Kilnamanagh Upper, was the territory of O'Dwyer Mac i Brien of Ara held the northern part of the barony of Owney and Ara. Another Mac i Brien held Coonagh which had not been included in the grant to Theobald Walter.

- ↑ The two baronies of Ormond paid a chief rent called the "Mart Early" which came to about £160: Esmond to Dorchester, Cal. St. PapR., 1630, p. 577. Apparently this was paid to the Earl of Ormond, hence the name.

- ↑ Some years before Strafford's time there had been various projects for a plantation of these districts. One is given at p. 150, Cal. St. Paps., 1647—60. Addenda, 1625—60, dated 1630. By this one-fourth was to be given to planters; the Earl, natives possessed of lands by virtue or pretence of patents and those having chiefries were to be favourably dealt with.

- ↑ It certainly included the baronies of Ormond. Rights and services due to the E. of Ormond from the cantred of Kilnamanagh are mentioned in Cal. St. Paps., 1607, p. 195.

- ↑ A full account of these transactions is to be found in Prendergast: Plantation of Ormond. Trans. Kil. Arch. See. Vol. I. (1849). Carte says that the young Earl helped Strafford by producing the title deeds: Prendergast with more reason says he refrained from producing them.

- ↑ One confiscation was actually carried through by Strafford. The territory of Idough—the greater part of the barony of Faesadinin in Co. Kilkenny—was taken from the O'Brennans who had held it for centuries, and given to Wandesforde, Master of the Rolls. On an inquisition it was found that the O'Brennans were mere Irish who had entered and "held by the strong hand, and that they therefore had no title."Wandesforde intended to compensate the dispossessed landowners: but his heirs got rid of their claims through the share they had taken in the events of 1641.

- ↑ From Strafford's time, too, date the Inquisitions taken after the King's title to Connaught had been found, giving particulars of the landed property of the province. They are in the Dublin Record Office.